You may or may not want to go to space, but here’s something certain: you definitely don’t want to get sick there. Ask the crew of Apollo 7, the 1960s mission in which the commander contracted a cold, spread it to the other two astronauts and all three of them spent the entire mission trapped inside a cramped spacecraft, sneezing, hacking and griping at the ground.

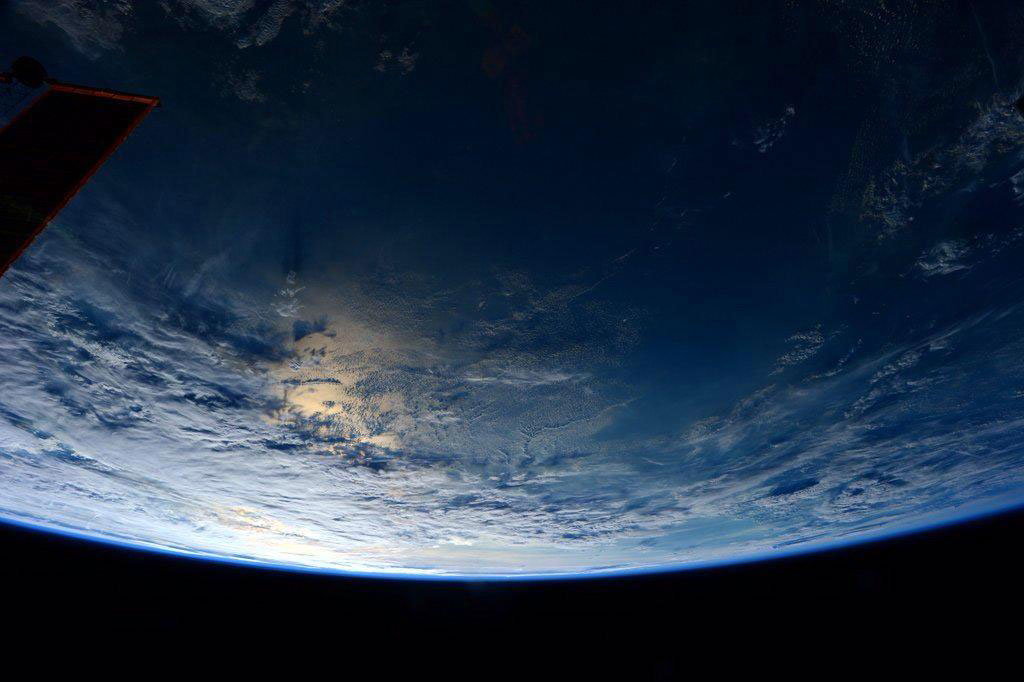

And that was just 11 days in Earth orbit. What about a year aboard the International Space Station (ISS)? What about a two-and-a-half-year mission to Mars. And what about something a wee bit more serious than a cold—like appendicitis or a heart attack or a severe injury? Zero-gravity plays all manner of nasty games with the bones, muscles, organs, eyeballs, the brain itself—never mind the infectious risks that come from sealing half a dozen people inside a self-contained vessel, where a virus or bacterium could simply circulate ’round and ’round, from person to person indefinitely.

These are some of the things that will be on the mind of rookie astronaut Kjell Lindgren, who will spend nearly six months aboard the ISS when he lifts off in late July as part of the station’s next three-person crew. Lindgren is not just a well-trained astronaut, but a specialist in aerospace and emergency medicine—just the kind of expert who will increasingly be needed as the human presence in space becomes permanent.

“If we want to go to Mars some day,” Lindgren said in a recent conversation with TIME, “if we want to get further and deeper into the solar system, we need to start thinking about these things, thinking about the capabilities we need to do an appendectomy or take out a gall bladder.”

There will be no gall bladder or appendix takings while Lindgren is aloft. For now, he and the ISS flight doctors back on Earth are taking only space-medicine baby steps, learning the basics about the radical differences between medical care on the Earth and medical care off it. Here are a few of the most vexing problems they have to learn to solve:

1. Where is that kidney again? On Earth, your organs settle into predictable positions. A doctor palpating your liver or thumping your chest knows exactly where things ought to be. In zero-g, not so much. “The organs may be displaced a little bit,” says Lindgren. “They tend to shift up a little more. The heart may have a little bit of a different orientation, which may be reflected on an EKG.” Other kinds of shifting or compression—of the lungs, stomach, bladder and more—can cause problems of their own.

2. Your bones hate space: Without the constant tug of gravity, your skeleton doesn’t work nearly as hard, which causes it to weaken and decalcify. Astronauts spend many hours a week exercising to counteract some of that, but nothing can reverse it completely. When Russia’s Mir space station was still flying, newly arriving cosmonauts were warned not to exchange traditional bear hugs with crew members who had been there for a while. The risk: broken ribs.

3. Your eyes do too: Astronauts who have been in space for long-term stays often find that their vision grows worse, and it doesn’t always bounce completely back when they return to Earth. The problem is caused by fluid shifting upward from the lower body into the head, compressing the optic nerve and distorting the shape of the eyeball. Eye infections and irritation are more common too—for decidedly ick-inducing reasons. “Dust doesn’t settle in the vehicle like it does on Earth,” says Lindgren. “So things that are liberated, little pieces of metal from equipment or maybe dead skin just float around and cause eye irritation.”

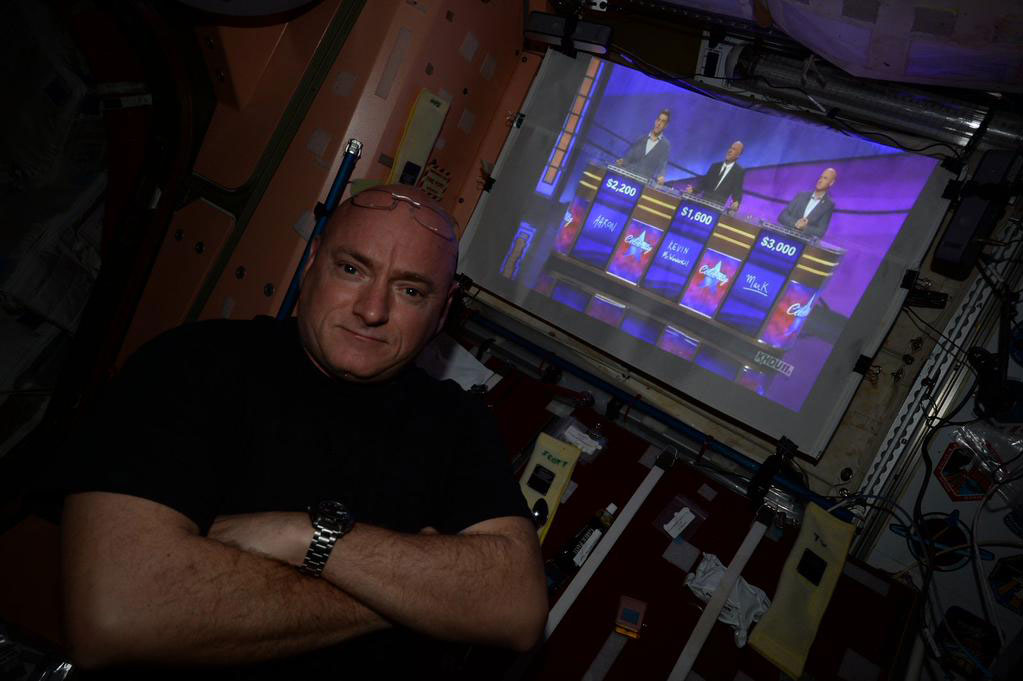

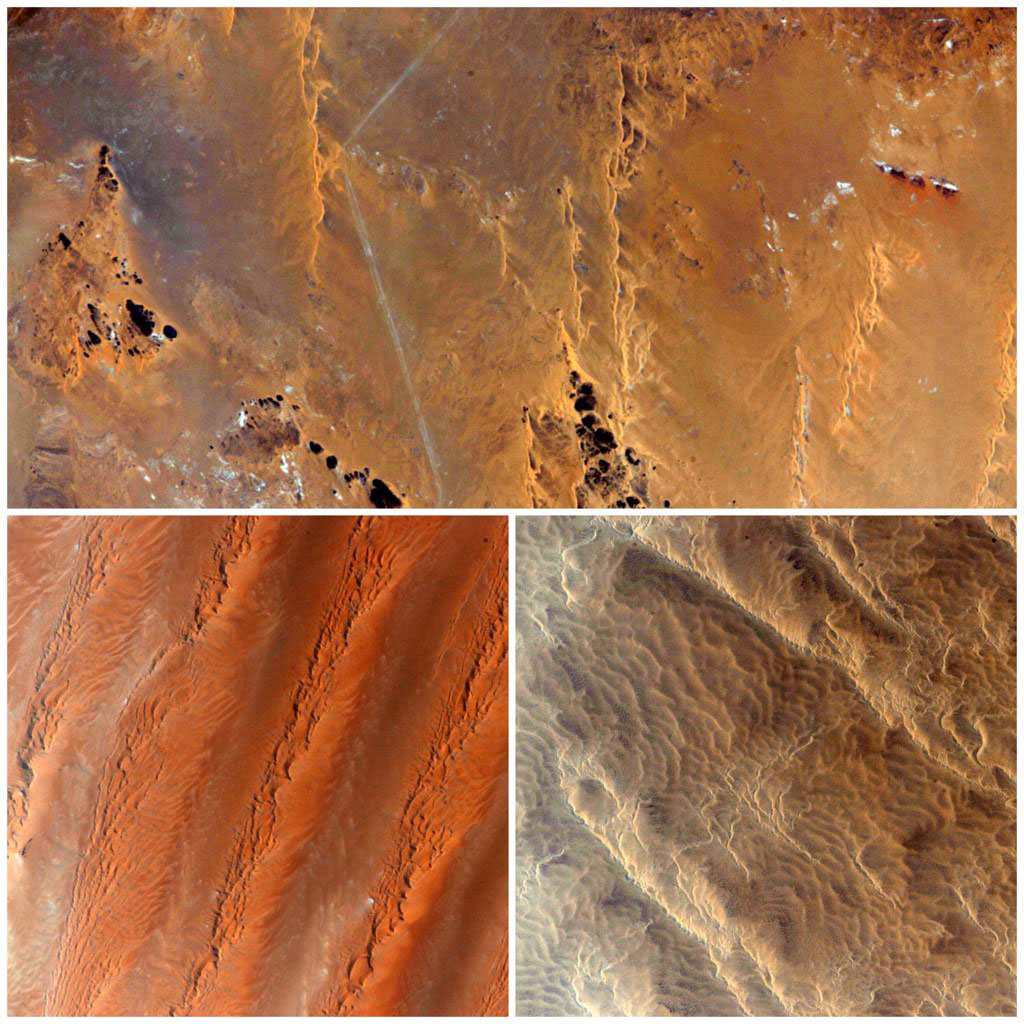

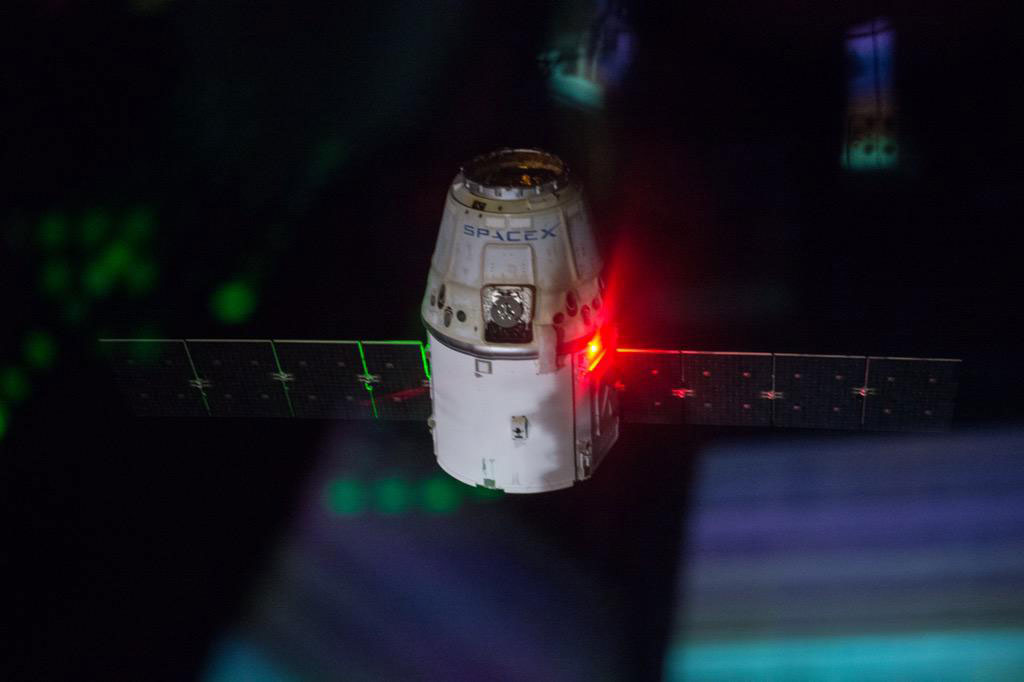

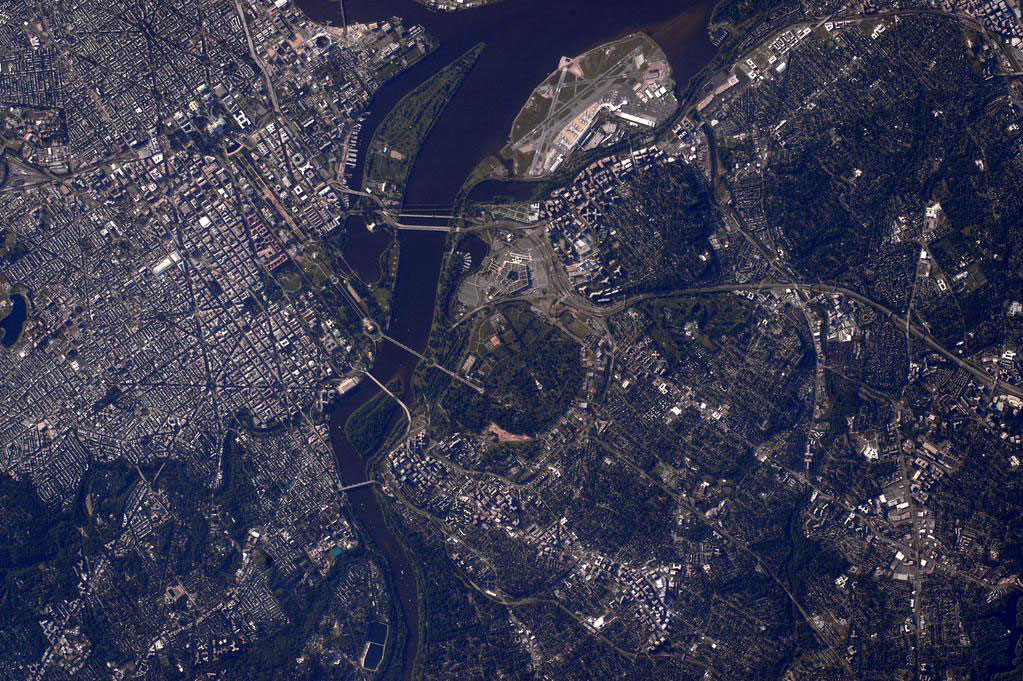

See Scenes From Astronaut Scott Kelly’s Second Month in Space

4. But your feet will thank you: You know all of those callouses that you’ve built up on your heel and the ball of your foot after a lifetime of walking around? Say goodbye too them. They serve a purpose, which is to cushion your foot against the shock of walking, but since you’re not walking in space, you don’t need them. Just beware when you remove your socks. The callouses don’t tell you when they’re going to slough off, so the wrong move at the wrong time could leave unsightly chunks of you floating around the cabin. (See, e.g., “ick-inducing,” above.)

5. Try not to need stitches: Suturing wounds is one of the most basic things doctors and other medical caregivers learn how to do, but it will take a little extra work in space. On Earth, sutures are simply laid on a tray along with the other equipment. In space, that’s not possible. “Instead of your sterile suture thread laying in a sterile field, now it’s floating around and running into everything,” says Lindgren. While aloft, Lindgren plans to experiment with different techniques to address this problem; no word on which of his five crewmates will volunteer to be the patient.

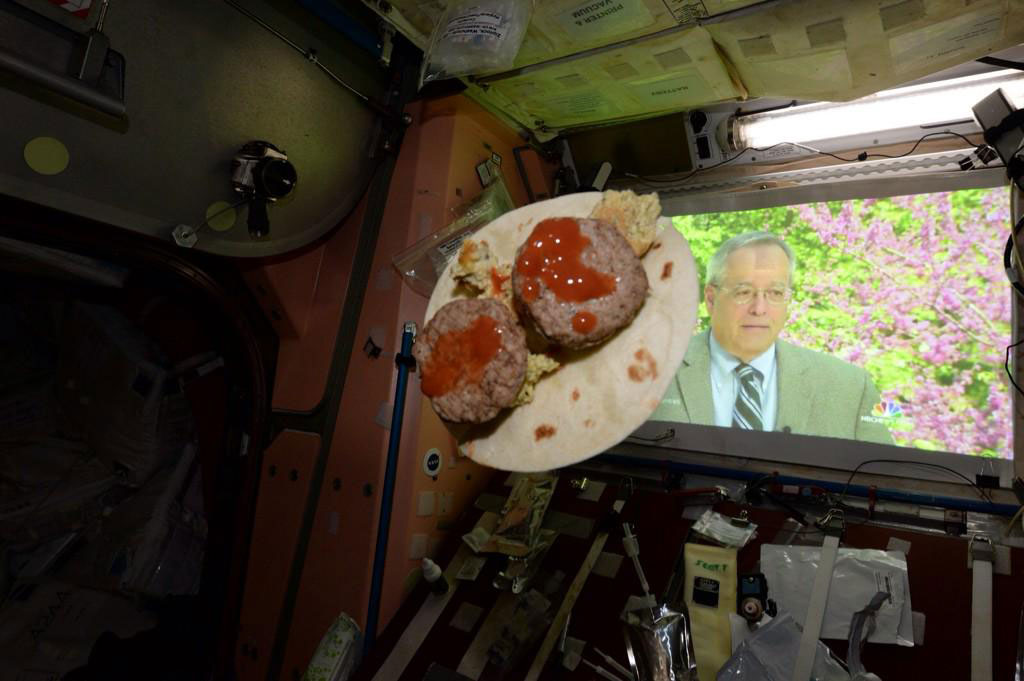

6. Eat your roughage: Easily the least glamorous part of space travel is the simple business of, well, doing your business. The space toilets aboard the ISS and the shuttle have come a long way from the bags and tubes of the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo era. But the human body hasn’t changed much in that time, and when it comes to keeping the intestines operating, a little gravity can help. One lunar astronaut who, for the sake of legacy and dignity will not be identified here, claimed that one of the best parts about landing on the moon was that things that hadn’t been working at all when he was in zero-g, got moving right away in the one-sixth gravity of the moon. History is made by mortals, and no matter where they are, mortals gotta’ do what mortals gotta’ do.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com