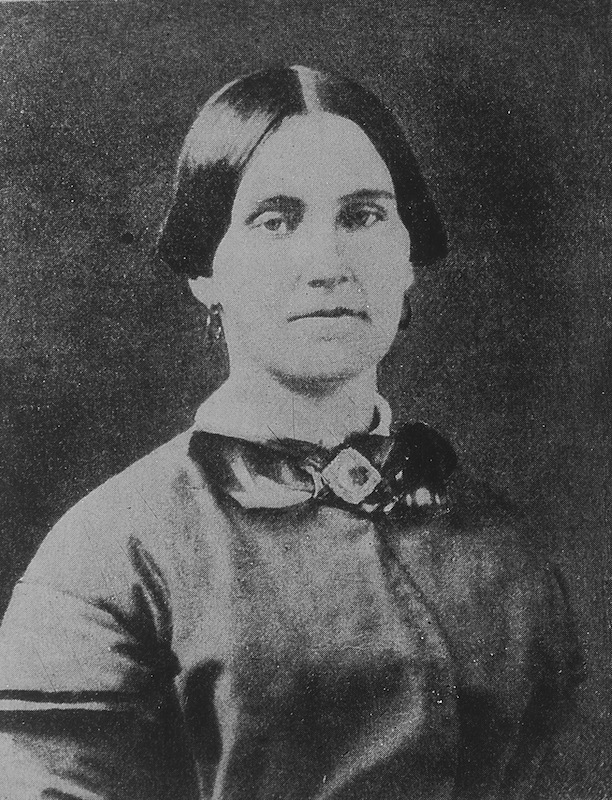

It’s been 150 years since the first conspirators who killed Abraham Lincoln were executed. Among them was Mary Surratt, who was the first woman to be executed by the federal government—but whose story remains a mystery to this day.

Surratt stands at the border of Civil War conflict. After all, she was from Maryland, a state that straddled North-South loyalties. As a child on a tobacco farm and, later, a farmer’s wife, Surratt’s loyalties skewed Southern and pro-slave: her family owned seven slaves. In 1851, her family farm burned to the ground, allegedly set ablaze by an escaped slave. By the time her openly secessionist husband died in 1862, her home was being used as a safe house for Confederate spies. The death of her husband, who was heavily in debt, led to a series of financial catastrophes for Surratt, which eventually prompted her to move to Washington, D.C. and open a boardinghouse in 1864. (The house, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is now a sushi restaurant and karaoke spot).

It’s unclear how much Surratt knew about the use of her boardinghouse—or the tavern she owned nearby—as a place of Confederate conspiracy. Her own son, John Surratt, Jr., was a member of the Confederate Secret Service, and by late 1864 her house had a frequent visitor, an actor named John Wilkes Booth.

On the night of Lincoln’s assassination, Mary Surratt’s boardinghouse was visited by members of another police force: The District of Columbia was seeking not only Booth, but also Surratt’s son, who was suspected of helping attack U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward, who was stabbed by one of Booth’s accomplices, Lewis Powell, as Lincoln was being attacked across town. One historian calls Mary Surratt’s testimony under police questioning “confident and arrogant.”

She claimed ignorance of any plot to kill the President, despite testimony from her tavern keeper that she had told him to keep guns at the ready on the day of the assassination. This testimony linked her to Booth and other conspirators, including her son. The tavern keeper, John Lloyd, reportedly cried out “Mrs. Surratt, that vile woman, she has ruined me!” when he heard of Lincoln’s murder.

Surratt was imprisoned in the Old Capital Prison along with the owner of Ford’s Theatre, Booth’s brother, Dr. Samuel Mudd and many other suspected co-conspirators. She was tried by a military tribunal instead of a civil court, a move that seems to have been motivated by lingering distrust between North and South, bitterness over the assassination and a desire to get to the bottom of the conspiracy.

At her trial, Surratt was defended by several priests and friends the New York Times called “constant and faithful.” But their testimony and her own protestations of innocence were not enough. Not only was she convicted, she was sentenced to death, along with the other alleged co-conspirators, on June 30, 1865. It was a move that shocked the country.

Despite last-minute attempts to gain clemency and commute her sentence to life in prison, Mary Surratt was executed by hanging on July 7 of that year. Dressed in black, she led the procession of prisoners to their death. Before she was hanged, she is reported to have asked the guard near her not to let her fall.

Surratt never stopped defending her innocence. Before being executed, the co-conspirator who attacked Seward claimed she was innocent (a debate that still continues to this day). But what of her suspected conspirator son? Just call him the one who got away: though he was tried in civil court in 1867, the government was unable to get him convicted—despite his admission that he had been part of a conspiracy to kidnap the President.

Correction: Aug. 7, 2018

The original version of this article misstated the nature of the attack on William H. Seward by Lewis Powell. Powell stabbed Seward, he did not shoot Seward. The original version of this article also misstated the intended use of the guns stored at Surratt’s tavern for the day of Lincoln’s assassination. Weaponry was stored for John Wilkes Booth, it was not used in the assassination itself. The original version of this article also mischaracterized the co-conspirators’ attitudes toward Mary Surratt. At least one defended her innocence, they did not defend her as a group. The original version of this article also misstated the result of John Surratt Jr.’s trial. It ended in a hung jury, it did not end in dropped charges.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com