The paperwork officially making Jeb Bush the third member of his family to seek the presidency arrived at the Federal Election Commission via courier on June 15, just hours before the former Florida governor’s son touched down in Reno, Nev. The 39-year-old George P. Bush, fluent in Spanish and with maternal roots in Mexico, was on a mission: pitch a crucial, diverse swing state on his father’s commitment to bringing the Republican Party into the 21st century.

“Republicans do not have to change their conservative views to gain Hispanic votes,” announced the younger Bush, the land commissioner of Texas. “My father believes we need to reach out and talk about our values and beliefs.”

When one potential supporter asked him in English if Jeb Bush would make his bilingual skills part of the campaign, the junior Bush took the bait: “Claro que sí,” he said–of course he would–before noting that he was already keeping score. Florida Republican Marco Rubio, another top-tier, bilingual Republican candidate, had also dropped a Spanish section into his announcement. But it was just a “few words,” George P. joked playfully. “Dad devoted a significant portion.”

It was a nice summary of a key subplot in the 2016 Republican race. Gone are the days when candidates tried to outmuscle each other with tough immigration rhetoric about longer, taller border fences or deeper moats. The new game is to show you are attuned to a fast-growing bloc of Americans whose political heft is set to double from 2012 to 2030.

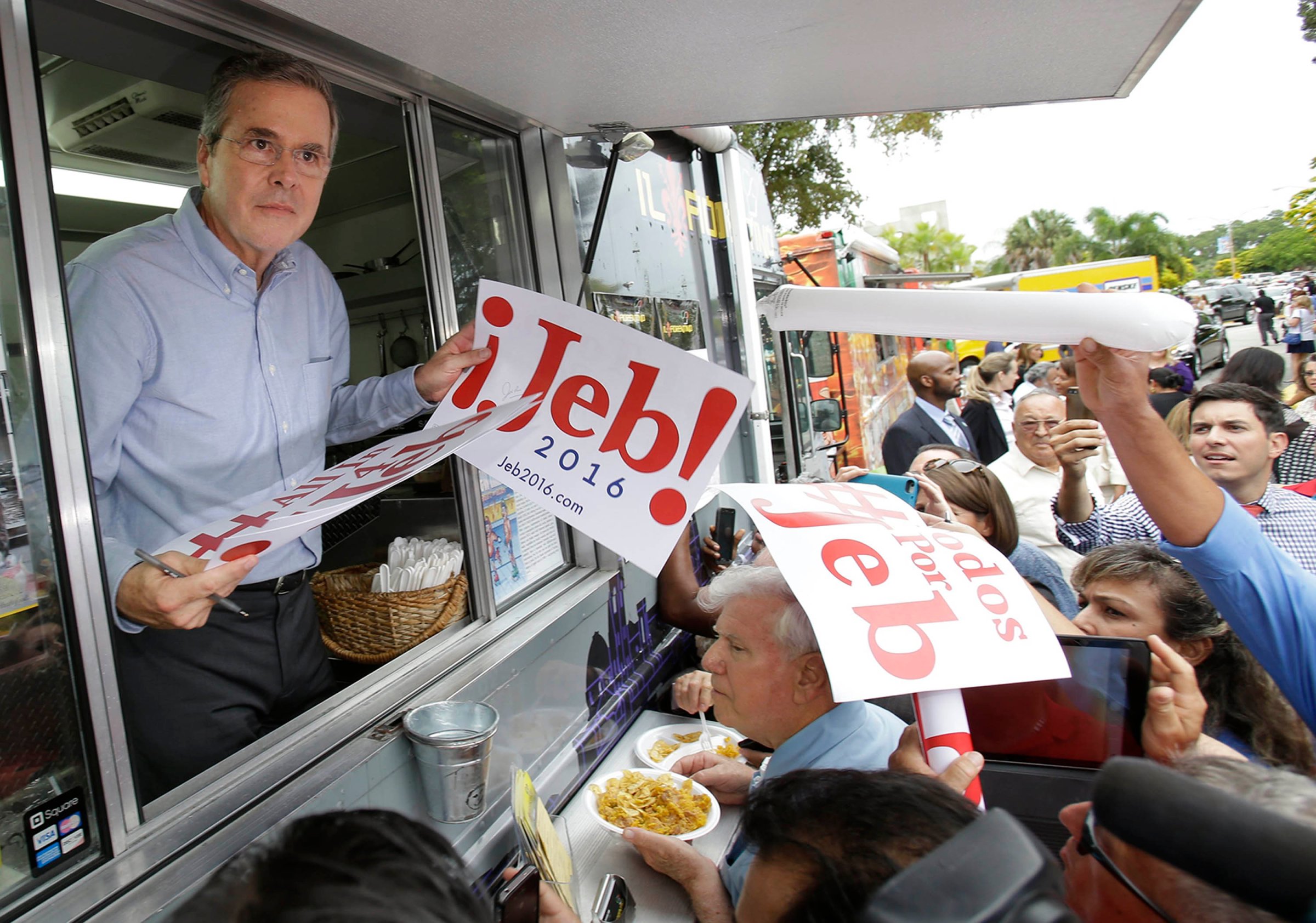

When pro-immigration-reform hecklers interrupted Jeb Bush’s kickoff speech near Miami, where salsa music blared before he came onstage, he didn’t dismiss them. Instead he told them he would work with Congress to overhaul the immigration system. He turned up days later on The Tonight Show With Jimmy Fallon to slow-jam in Spanish and tout his guacamole-making skills. And when he sat down with ABC News’ David Muir in Iowa, the two conducted part of their interview in Spanish.

It’s an approach that has begun to break through on the ground in Nevada, where Barack Obama won 71% of the Hispanic vote in 2012. That new effort could be good news for Republicans, who have scant chance at reclaiming the White House without performing better than 2012 nominee Mitt Romney did in Latino-rich states like Florida, Colorado and Nevada. “When you listen to Jeb Bush speak, you think he’s one of us. I don’t feel that with Marco Rubio or Ted Cruz. Jeb Bush is closer to us,” says Jesus Marquez, a 40-year-old Las Vegas resident and first-generation Mexican American who met George P. Bush when he visited a Mexican restaurant in Las Vegas. “His kids are Mexican American, basically.”

These are the sounds of a party trying to rebrand itself. As recently as a couple of years ago, a bipartisan effort to overhaul the nation’s broken immigration system passed the Senate only to die in the Republican-led House, as the rank and file rebelled at the notion of a path to citizenship for immigrants in the country illegally. From the sidelines, conservative pundits jeered the reform effort, which was led by future White House hopefuls Rubio and Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina. The effort went nowhere.

Lately the jeering voices have been more muted and belong to fringe figures like Donald Trump, who announced his campaign by describing most Mexicans who cross the border as criminals and rapists. (“Some, I assume, are good people,” he added in an aside.) But Republican voters, even in early primary states, appear open to argument. Bush and Rubio, who both say they would sign a bill offering a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants under the right circumstances, now find themselves atop the GOP polls nationally; a recent NBC/Wall Street Journal poll found that three-fourths of Republicans could see themselves supporting either Floridian for President, placing them both well ahead of the rest of the field. “Clearly, folks are doing the math, and they understand that Latinos are going to decide who the next President is,” says Cristóbal Alex, president of the Democratic-backing Latino Victory Project.

This shift began months ago. After Romney’s bruising loss in 2012, in which he suggested that the undocumented “self-deport,” the Republican National Committee convened a commission of some of the GOP’s brightest–and most outspoken–operatives to figure out how to avoid a repeat loss. Sally Bradshaw, Jeb Bush’s longtime consigliere, was among the five co-chairs of the effort that produced a brutally blunt report, dubbed internally “the autopsy.” “Unless the RNC gets serious about tackling this problem, we will lose future elections,” the Bradshaw-led commission concluded. “Hispanic voters tell us our party’s position on immigration has become a litmus test, measuring whether we are meeting them with a welcome mat or a closed door.”

Not all are convinced. Two other presidential contenders, Senator Ted Cruz of Texas and Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky, voted against Rubio’s immigration bill, even as Paul embraced the idea of a path to citizenship. Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker, who once backed a pathway to citizenship, reversed course this year to call for tougher limits on even legal immigration.

By next year, Hispanic support may matter nowhere more than in Nevada. Its Latino population almost doubled from 2000 to 2010 and now accounts for 16% of the electorate. An estimated 210,000 Nevadans are in the state illegally–almost 8% of the population and 10% of its workforce. At the same time, 18% of its K-12 students have at least one parent with dodgy immigration standing. The GOP’s challenge is not going to age out, as the demographers say.

Yet even in Nevada, Republican efforts to embrace Latinos are no better than halfhearted. As George P. Bush left the state, the major umbrella group for Latino elected and appointed government officials from around the country was flying in for an annual conference. Democratic front runner Hillary Clinton and her top rival, Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, addressed the crowd, while Rubio and Cruz–both elected officials that the conference is supposed to draw–stayed away.

In their absence, representatives for the LIBRE Initiative, an effort funded in part by Republican donors Charles and David Koch to reach out to Latinos, worked the crowd, trying to convince officials that conservatives weren’t fire-breathing monsters. “When a conservative engages with the Latino community and respects them and makes the case on ideas, you’re going to be rewarded,” executive director Daniel Garza says.

There were inklings of Democratic concern. When asked if a presidential candidate like Bush could do well among Hispanic voters, Representative Ruben Gallego, an Arizona Democrat, let out a sigh. “It could happen,” he said.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Philip Elliott / Las Vegas at philip.elliott@time.com