Friday’s news that the United States Supreme Court has ruled that all states must issue licenses for and recognize marriages between same-sex couples comes after years of anticipation among advocates and allies. Plenty of ink has been spilled about the speed with which the idea went from political poison to a seeming inevitability—but the story of marriage equality in the United States is actually much longer than is often acknowledged.

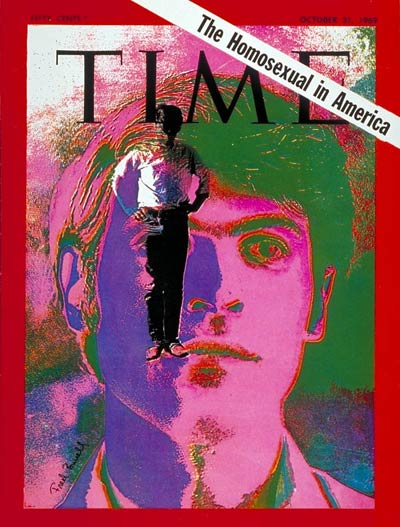

One of the first instances of same-sex marriage being discussed in the pages of TIME was in 1969, as part of a round-table discussion on the question “Are Homosexuals Sick?” in an issue with a cover story on The Homosexual in America. (That’s the cover, at left.) At one point in the conversation, one Rev. Robert Weeks proposed that it wasn’t so easy to say whether homosexuals as a group were “sick” or not:

I just finished counseling a person who was addicted to the men’s room in Grand Central Station. He knows he is going to get busted by the cops; yet he has to go there every day. I think I did succeed in getting him to cease going to the Grand Central men’s room, perhaps in favor of gay bars. This is a tremendous therapeutic gain for this particular man. But he is sick; he does need help. However, I don’t think Dr. Socarides [another participant, a psychoanalyst] is talking about people like another acquaintance of mine, a man who has been “married” to another homosexual for fifteen years. Both of them are very happy and very much in love. They asked me to bless their marriage, and I am going to do it.

Robin Fox, an anthropologist participating in the discussion, concurred: “So far as the two ‘married’ individuals are concerned,” he said, “they are engaged in what to them is a meaningful and satisfying relationship. What I would define as a sick person in sexual terms would be someone who could not go through the full sequence of sexual activity, from seeing and admiring to following, speaking, touching, and genital contact. A rapist, a person who makes obscene telephone calls—these seem to me sick people, and I don’t think it matters a damn whether the other person is of the same sex or not.”

The notion of gay marriage wasn’t just theoretical. Same-sex couples around the country were already starting to push for legal unions.

In October of 1970, a man named James Michael McConnell was fired by the University of Minnesota after applying for a marriage license with his partner. A district court judge ruled that the university couldn’t fire McConnell over it, as “the homosexual is as much entitled to the protection and benefits of the laws as are others.” The following year, McConnell was back in the news with an enterprising solution to his problem: ultimately unable to use marriage to make their relationship legal, he adopted his partner. The ruling that allowed the adoption was, the Gay Activists Alliance told TIME that week, the first of its kind. And it came with benefits: their new household status suddenly opened the door for tax deductions, tuition discounts and inheritance rights. They were living proof that legal acknowledgement of a relationship conferred tangible rights. (As of a May 2015 New York Times profile, they were still together).

By the time the 1972 Democratic National Convention rolled around, the idea of marriage equality—though far from mainstream—was real enough to make it to Miami, where the delegates would meet. As TIME reported, the largely youthful cohort that supported George McGovern included Americans who were ready to push the envelope for change, “demanding platform planks in favor of legalized marijuana, abortions on demand and homosexual marriage.”

Except, of course, McGovern lost the general election to Richard Nixon.

That same year, 1972, the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) passed Congress. Though the ERA, which said that “equality of rights under law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex,” passed Congress, it failed to be ratified by enough states, even after a multi-year fight. Foes of the measure warned that it could open the country to a future full of unisex bathrooms, military conscription for women and, yes, legalized gay marriage.

TIME called the threat “exaggerated” and noted that even at the 1977 National Women’s Conference, where lesbian rights were on the agenda, many progressive leaders wanted to distance themselves from LGBT issues (not that they were called that at the time) for fear of lending ammunition to ERA foes. In 1981, as the ERA was on its last legs, speakers for the National Organization for Women accused the Stop ERA campaign led by Phyllis Schlafly of spreading word that the ERA would lead to “approval of homosexual marriage or the breakup of the family,” in TIME’s words. But their protestations weren’t enough. In 1982, the clock ran out on the ERA.

How Gay Life in America Has Changed Over 50 Years

Despite the use of same-sex marriage as a scare tactic, momentum for the idea began to build again in the 1980s. Individual municipalities and businesses began to grant benefits to domestic partners, and by the end of the decade there was growing, if still small, support for extending some legal protections typically associated with marriage. In the years since a TIME survey in 1989 showed that more than two-thirds of respondents opposed recognizing the marriage of same-sex couples, public opinion has essentially flipped in favor of the unions.

Perhaps Phyllis Schlafly was right. Given America’s turnabout on gay marriage, it’s distinctly possible that the ERA could have helped marriage equality arrive even faster. Nor was Schlafly the only one who might have guessed correctly. In 1975, TIME interviewed a Columbia Law professor about the possible implications of the amendment. The professor said that women who expressed fear of the ERA were really just afraid of change, but conceded that it was impossible to know what the eventual results would be of such a broadly worded addition to the Constitution. That professor’s name was Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Read TIME’s 2013 cover story on marriage equality: How Gay Marriage Won

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com