This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

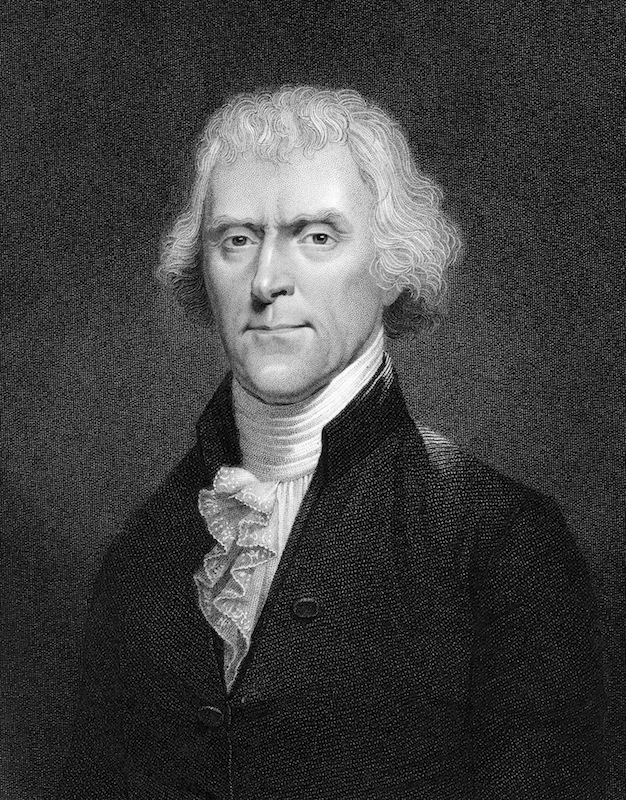

On June 4, 1781, nearly five years after authoring the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson fled Monticello just minutes before the arrival of British troops. His term as governor of Virginia had just expired, and Jefferson declined to continue his service, leaving the state without leadership during some of its darkest days.

In his defense, Jefferson made a blunt admission. With Virginia under invasion by a “powerful army,” Jefferson felt he was unprepared by his “life and education for the command of armies.” As a result, Jefferson wrote that he “believed it right not to stand in the way of talents better fitted than his own to the circumstances under which the country was placed.”

The legislature eventually appointed a governor and launched an investigation into Jefferson’s conduct. When Jefferson later sought the presidency, his conduct would be used against him. He was called the “coward of Carter’s Mountain,” a reference to the woods that Jefferson traversed when he was in flight from Monticello. Another critic, a South Carolina congressman named William Loughton Smith, said Jefferson deserved little credit for his revolutionary writings because he had fled “in times of danger.” There was no great merit in composing “famous written works,” Smith said, if he had done so “without risk of personal convenience.” Jefferson felt so burdened by accusations against him that he wrote that the wound upon his spirit would be cured only by the “all-healing grave.”

Jefferson clearly was ineffectual at stopping the waves of invading British forces, led first by the traitor Benedict Arnold, then by William Phillips (whom Jefferson once had entertained at Monticello when Phillips was a prisoner of war) and finally by Lord Cornwallis and Banastre Tarleton. Jefferson spent much of his life defending himself against the charge of cowardice, and tried until nearly the day that he died to present his side of the story to historians. Indeed, there was blame to go around. The militia often were reluctant to turn out. Many members of the legislature and the Governor’s Council fled Richmond, prompting the Assembly’s relocation to Charlottesville and culminating in Jefferson’s flight from Monticello.

But what did Jefferson learn when he was literally on the run, at a time of such torment?

Like so much about Jefferson, the lessons may seem contradictory, but they help explain the man – and president – that he became.

Jefferson, of course, wanted a weak executive as governor of Virginia because of his concerns about putting too much power in the hands of a man who might then become a new tyrant. He also had concerns about the power of a standing army. In the early weeks of the invasion, he was reluctant to go too far in calling out militia, which had been subject to false alarms. Some militia men were also concerned about leaving their families and farm undefended, and did not have the proper clothing or arms.

Indeed, when the Continental Army officer Baron von Steuben repeatedly complained about Jefferson’s inability to turn out militia and supplies, Jefferson responded weakly: “We can only be answerable for the orders we give and not for their execution. If they are disobeyed from obstinacy of spirit or coercion in the laws, it is not our fault.”

But as the British continued to march at will across the state, and as Jefferson learned of draft riots and mutinies, he finally seemed to have an epiphany.

“Go and take them out of their Beds, singly and without Noise,” Jefferson wrote about recalcitrant militia. If they were not found the first time, Jefferson continued, “go again and again so that they may never be able to remain in quiet at home.”

Years later, Jefferson conveyed a lesson to one of his successors in the governorship. A governor should not worry about gaining approval for every action in the event of an invasion if other government officials are unavailable, Jefferson explained. Such a delay “might produce irretrievable ruin.” Jefferson did not believe that the framers of the Constitution intended that its words should be followed so rigidly “that the constitution itself and their constituents with it should be destroyed” due to the lack of authority to repel invaders. Thus, Jefferson concluded, “an instant of delay in Executive proceedings may be fatal to the whole nation. They must not therefore be laced up in the rules of the judiciary department.”

Jefferson, of course, had been responsible for considerably more than “an instant of delay” when the British invaded Virginia, but, he insisted, he had acted when necessary. Jefferson’s Federalist enemies would say Jefferson failed to learn the lesson of the invasion, namely, that a stronger federal force was needed. Jefferson, however, believed the system had somehow succeeded, with the militia eventually turning out and the British defeated with help from the Continental army and French forces.

Twenty years after the invasion of Virginia, Jefferson sought the presidency in part because he was concerned that Federalists would be too quick to wage an unnecessary war against a European power. He considered his victory of 1800 a second American revolution, believing the “reign of witches” had ended.

As president, Jefferson applied another lesson of the invasion of Virginia when he signed legislation that established a military training academy at West Point. The British had easily gotten past Virginia’s defenses, and Jefferson hoped that the academy would produce men who would design better defenses and educate officers who were in line with his thinking.

Then, throughout the eight years of his presidency, Jefferson sought to resist those in Congress whom he believed would push the nation into war. While he did send vessels against Barbary States pirates and vowed that the nation would fight “like men” if a war was necessary, he used an array of measures, including treaties and a controversial embargo, in an effort to avoid a major military conflict. Time and again, Jefferson wrote friends of his desire to keep the nation at peace based on what he had experienced during the Revolutionary War.

“I think one war enough for the life of one man,” Jefferson wrote a friend in 1808, “and you and I have gone through one which at least may lesson our impatience to embark in another.”

Michael Kranish is the author of “Flight from Monticello: Thomas Jefferson at War,” published in February 2010 by Oxford University Press. He can be reached through his website, http://www.michaelkranish.com.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com