As South Carolina officials have united behind a push to remove a Confederate flag that flies in the state capital, focus has shifted to the last state that includes the controversial banner in its flag: Mississippi.

In the last few days, several prominent Mississippi legislators have supported a redesigned flag without Confederate symbols after the shooting in Charleston, S.C. that left nine people dead at a storied black church. The alleged shooter, Dylann Roof, was seen in several photos following the shooting posing next to the Confederate States of America flag.

“I believe our state’s flag has become a point of offense that needs to be removed,” Republican House Speaker Philip Gunn said in a statement. “We need to begin having conversations about changing Mississippi’s flag.”

Others, including Secretary of State Delbert Hosemann, have signaled they’d be open to changing it, while Lt. Governor Tate Reeves appears willing to let the people decide in a future referendum. Democratic State Senator Kenny Jones says he is marshaling bipartisan support to pre-file legislation that will be taken up when the legislature is in session in January and will ultimately need two-thirds of the legislature to sign any change into law.

“In 2001, the conversation centered around the flag being disrespectful and appalling to African-Americans, but at the same time it was about the heritage to the white community,” Jones says. “Now, the conversation is different. Now it’s about how this symbol represents hatred, violence and bigotry. Now it’s about what can we do to make our state more progressive but in a bipartisan way.”

But changing a symbol that has flown in Mississippi for more than a century is a far greater challenge than removing one flag at the South Carolina statehouse. For one, there is little political will within the Republican-dominated legislature to do so, says John Bruce, a University of Mississippi political science professor. “The dominant thread of ideology in the Republican party in the state is to pick up the flag, wave it and say, it’s state’s rights,” Bruce says. “Not to say that that’s everybody, but the tenor of the party will not find it particularly objectionable.”

While several states still include remnants of Confederate symbols in their state flags, Mississippi is unique. The primary symbol on the flag is a smaller version of the Confederate battle flag, which to many black Americans recalls an earlier era of slavery and discrimination, but to some white communities symbolizes Southern heritage. Originally designed in 1894, the Mississippi flag came under scrutiny in 2001 during a referendum led by the Mississippi Economic Council, the state’s chamber of commerce, which argued that it hurt tourism and businesses looking to relocate to the state.

“The great argument we made from a business perspective was that if you were trying to introduce a product, would you make something that made 38% of your market uncomfortable?” says Blake Wilson, CEO of the Mississippi Economic Council, referring to the black population in the state. “It was a no-brainer from our perspective, but we probably misjudged the ability for business to influence the general public. The people in Mississippi were not ready to take that step.”

Two-thirds of Mississippians backed the old flag over one that had been redesigned without any Confederate symbolism. Ole Miss’s Bruce says that the alternative flag was not particularly well liked and that many Mississippians saw no threat from businesses that may not want to set up shop because of the flag. “I think the mood was, We’re a poor, agrarian state anyway,” Bruce says. “You can’t hurt us.”

And there’s little to suggest that much has changed since then. Only a handful of Mississippi’s 174 state legislators have signaled that they’ll consider even debating a motion to change it. The state’s 97 Republican legislators will likely be opposed to any change, and there’s still one important hold-out: Republican Governor Phil Bryant, who essentially warned legislators on Tuesday not to attempt to override 2001’s referendum.

“A vast majority of Mississippians voted to keep the state’s flag, and I don’t believe the Mississippi Legislature will act to supersede the will of the people on this issue,” Bryant said in a statement, according to the Associated Press.

Bruce, the Ole Miss professor, says that even with momentum in South Carolina and around the U.S. in support of removing that state’s Confederate flag, he believes there won’t be enough political support to change it in Mississippi, especially if the governor is opposed.

“We haven’t had the shock South Carolina has had,” Bruce says. “Changing the flag would likely take something that throws us into the national news with that symbol and that conversation that we can’t run away from.”

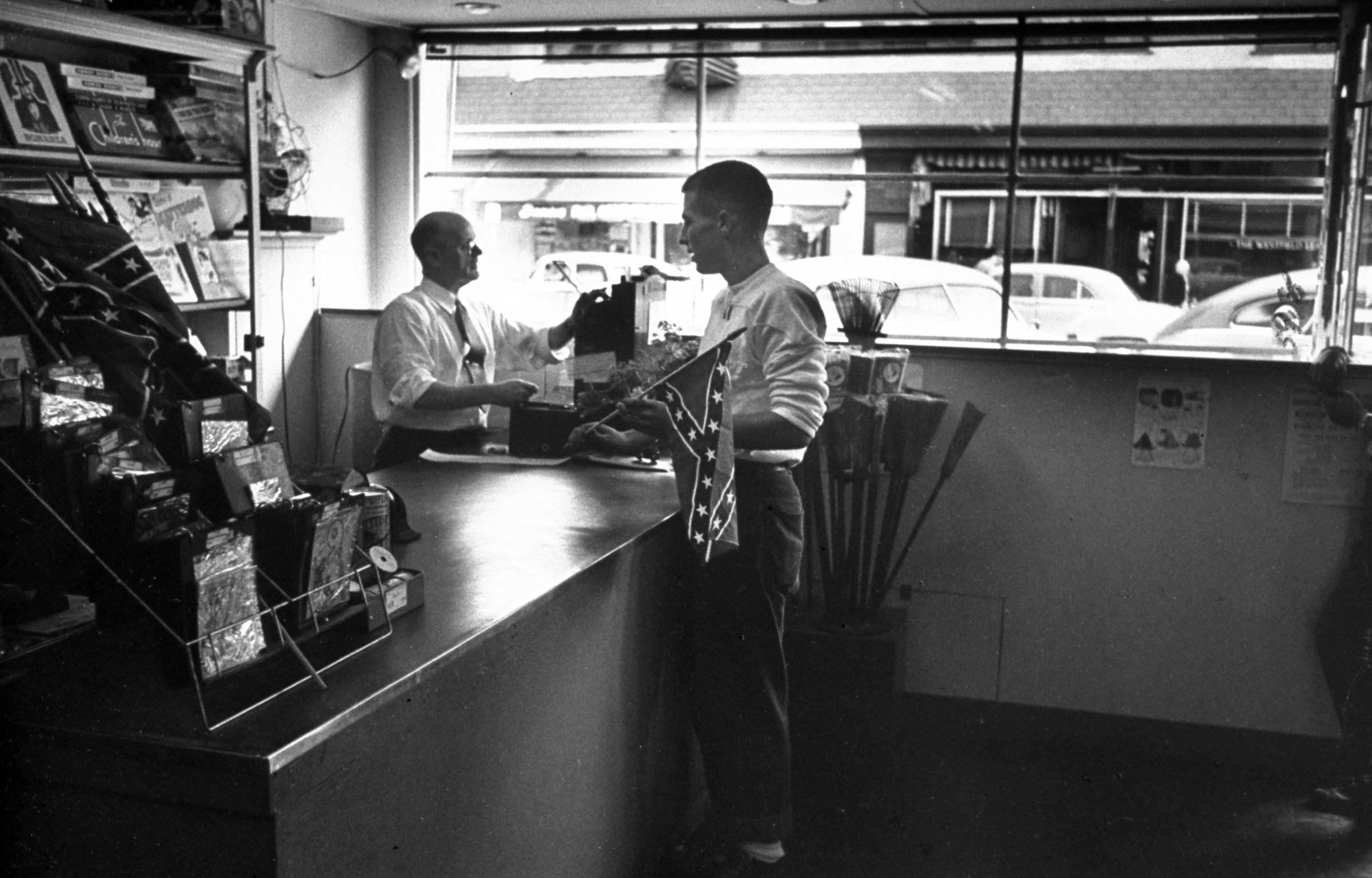

When the Confederate Flag Seemed Like a Fad

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com