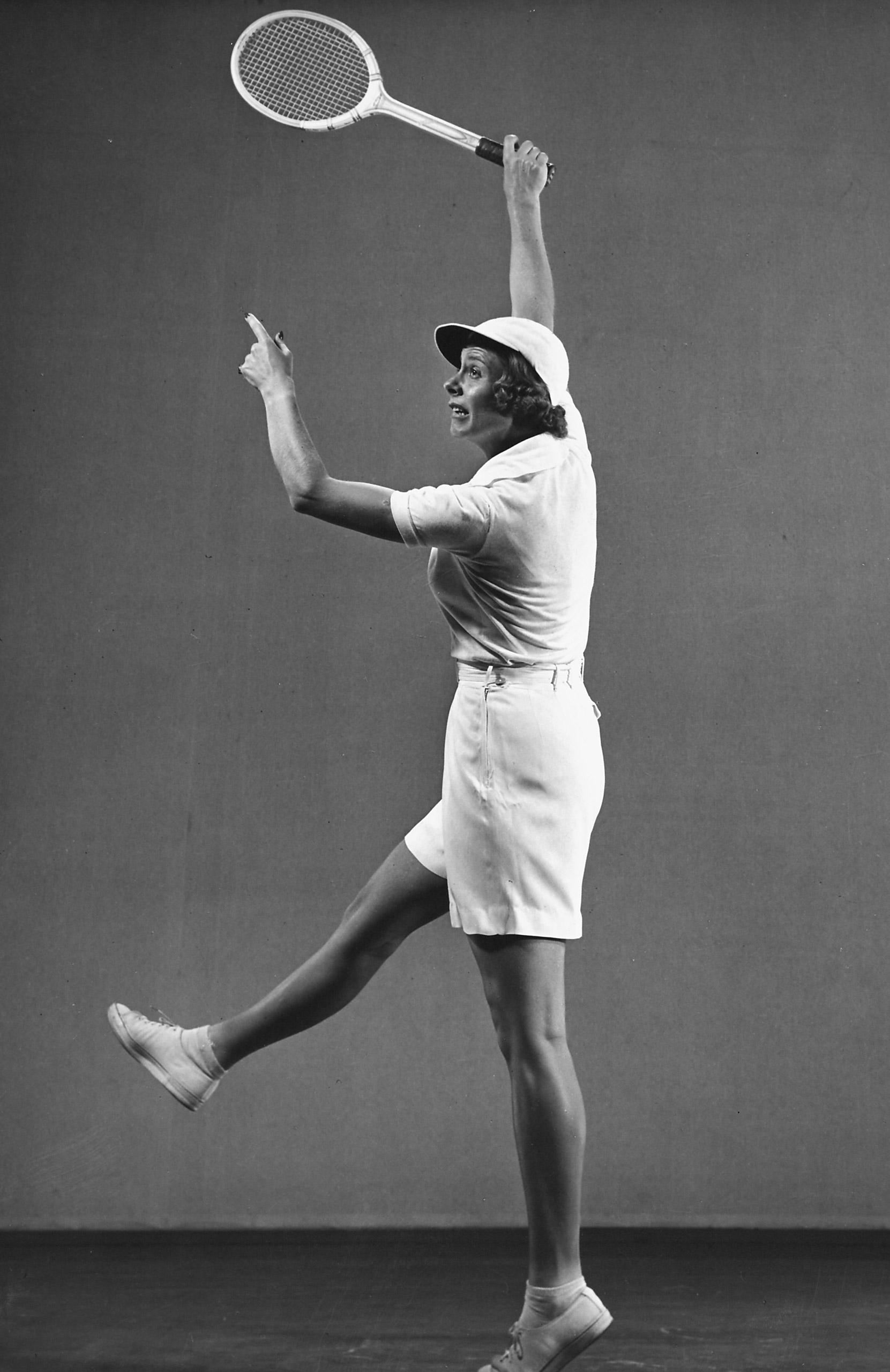

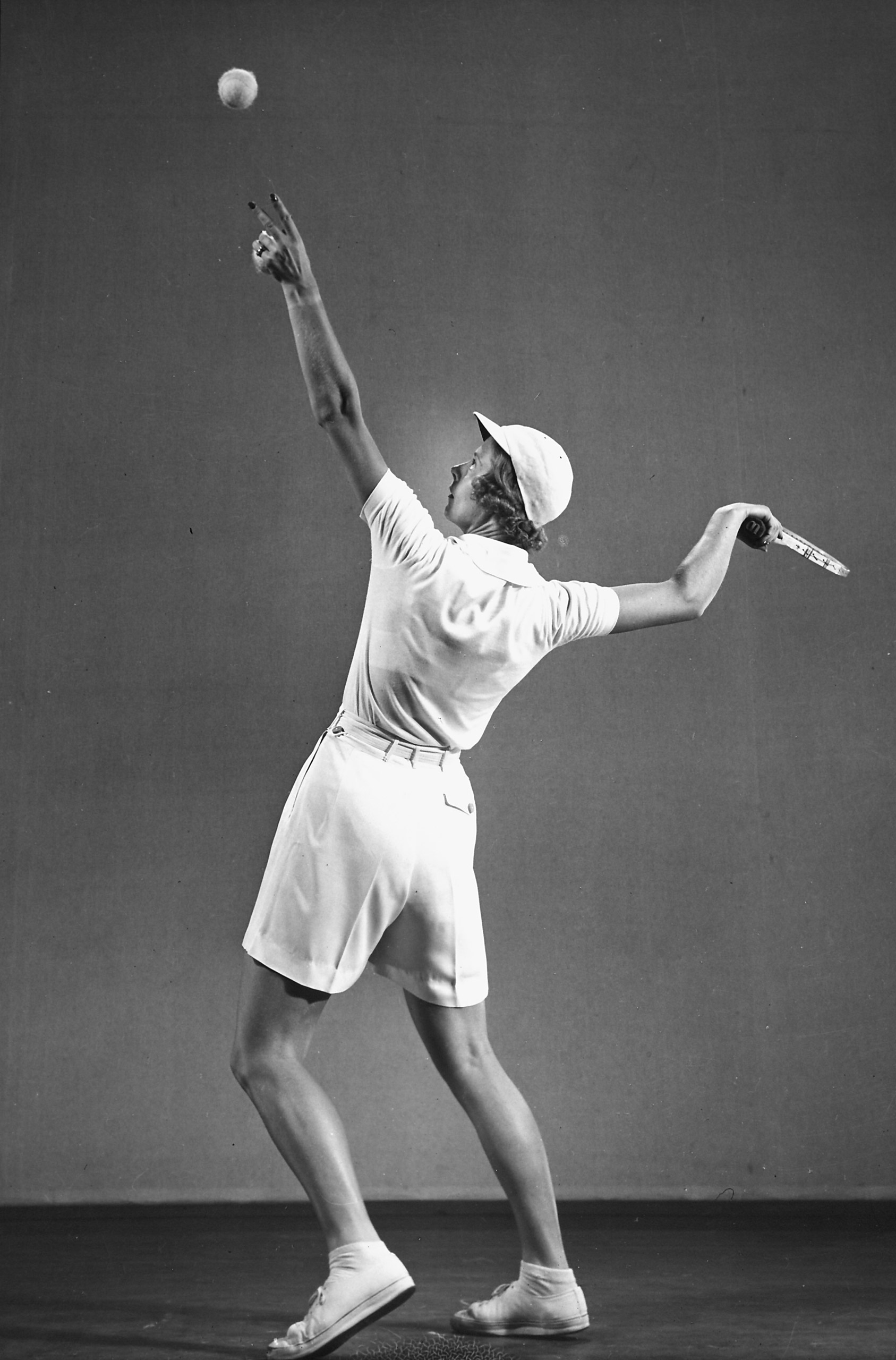

Alice Marble’s tennis career was enough to make her a legend. She was the No. 1 female player in America between 1936 and 1940, a winner of 18 Grand Slam championships, an International Tennis Hall of Famer and the first woman to adopt the serve-and-volley style of play. Her aggressive nature on the court led some to say (critically) that she played like a man.

But it’s the fascinating life Marble lived off the court that makes her more than just a memorable athlete. By the time her career got underway, Marble had overcome a great deal of adversity. In her second autobiography, Courting Danger, she recounted being raped by a stranger when she was 15, a trauma that she hid from her mother out of shame. Then, as her career was taking off in her early 20s, she fell ill with tuberculosis and required a year of recuperation.

After putting her decorated tennis career behind her, Marble made a bit of a career pivot. DC comics approached her to solicit—as they did from many notable athletes—an endorsement for their new superhero, Wonder Woman. Instead of offering a sentence of support, she became an associate editor of the comic, establishing a new weekly feature called “Wonder Women of history…as told by Alice Marble,” in which she told the stories of women like Florence Nightingale in comic form.

World War II brought new adventures, although for Marble they began with a double tragedy that led to a failed attempt to take her own life. Days after she miscarried a pregnancy, her husband Joe Crowley, a fighter pilot, was killed in action. Inconsolable, Marble reported in her memoir that she accepted without hesitation when the government approached her about operating as a spy in Switzerland—a mission revealed only after Marble’s death, when her book was published. “I felt I had nothing left to lose but my life,” she wrote, “and at the time I didn’t care about living.”

Marble’s mission to obtain Nazi financial information was cut short when she was shot in the back by a Nazi operative.

But the story doesn’t end there: after recovering and reestablishing herself in the U.S, she set her sights on a new cause, the racial integration of tennis. Her July 1950 editorial in American Lawn Tennis Magazine advocated for fellow player Althea Gibson to be allowed to play in U.S. Lawn Tennis Association competitions; it was the first major public challenge to the establishment’s practice of segregation. “If tennis is a game for ladies and gentlemen, it’s also time we acted a little more like gentlepeople and less like sanctimonious hypocrites,” she wrote. Marble’s letter was a major contributing factor in Gibson’s invitation to play in the tournament now known as the U.S. Open.

Before Wonder Woman and the Nazis, back in 1939 when Marble was at the pinnacle of her career, LIFE put her on its cover. In the story, the magazine chided the rest of the media for focusing on Marble’s glamor when in fact she was all about grit. (She did, after all, choose comfort over glamor on the court, where she eschewed the tradition of ladies wearing skirts and opted for shorts instead.) As LIFE wrote:

Newspaper writers like to think of Alice Marble as a glamor girl. They prattle about her beautiful clothes, her night-club singing, her movie offers. They call her the “streamlined Venus of the tennis courts.” All this is nonsense. She is a pretty girl who looks well in shorts. Her arms and legs are too long and muscular, and she plays too much of a slambang game of tennis to be glamorous…Even today, at 26, she is somewhat of a tomboy, hits a tennis ball harder than do most men. In fact, if she had her way, she would play only in men’s tournaments.

Marble was a Grand Slam-winning, spying-on-Nazis, comic book-editing champion for equality. It’s a wonder we’re still waiting on the Hollywood biopic.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter @lizabethronk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com