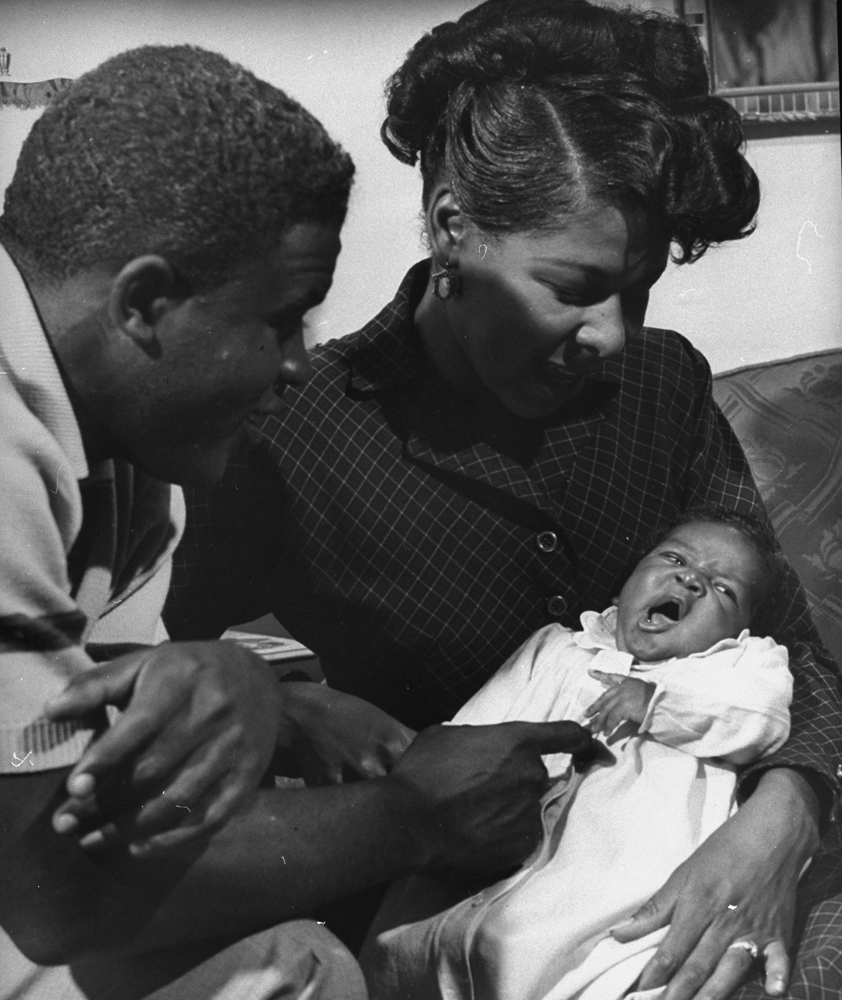

On a cold November morning in 2007, my wife Katherine had a fatal car accident. Forty-five minutes before she died, our daughter Isabel was born, a miracle of health rescued by an emergency cesarean. After Isabel defied the odds to make it into the world, I went from taking her life for granted to being unable to look at her without my heart racing. I had become her biological father in a grisly instant; becoming her dad would take years.

I hadn’t reflected on what fatherhood meant before her birth. My preconceived notions of a father’s roles—breadwinner, patriarch, protector—belonged to an outdated playbook, one created in Calabria, an impoverished southern Italian region where my father, Pasquale Luzzi, was born. Drafted into the Italian army as a young man, he barely survived World War II, and immigrated with his wife and four small children to the U.S. in 1956, where he would spend his days doing backbreaking factory work. My father was the kind of man who, as my pregnant mother was delivering his children, stayed clear of the hospital and chose instead to visit the social club to drink wine and play cards.

After Katherine’s death, I relied on my family, especially my widowed mom and my four sisters. This freed me for jaunts to the playground with Isabel, vanilla ice cream with her on the beach, and father-daughter sing-alongs at the local music program. I had been raised according to the gender dictates of ancient Calabria. I grew up watching my mother tend to my father like an aide-de-camp after his debilitating stroke 13 years before he died. I would never have admitted as much, but to me it was taken for granted that my mother would change Isabel’s diapers while I slept soundly.

Yet with each midnight diaper changing that I slept through, with each afternoon nap when I fled the house to play tennis or work on my book, Isabel’s infancy was slipping through my fingers. My mother was devoted to Isabel, but she was in her 80s, and her regime of feeding my daughter consisted of goods that you could pick up at the gas station.

I was living under the spell of what Joan Didion called “magical thinking”: the cool-minded craziness of those who expect their loved one back at any moment. I knew that Katherine wasn’t coming back for those knockout leopard-print shoes she wore the night I met her. Mine was a different kind of magical thinking: the sense that the world began and ended with my own suffering. My grief became an airtight shell, and contrary to my calm outward appearance, my sorrow now defined me.

Worst of all, my sorrow was keeping me from forming an emotional attachment with Isabel. I loved her, but I did not feel that instinctual protectiveness that should have made her needs the center of my world. This was grief’s greatest exile: the separation I felt from my flesh and blood. The smallest tasks associated with her care flustered me. The prospect of arranging her gear for our outings—the network of bottles, diapers, and bibs—could send me into paroxysms of anxiety, as could the slightest outburst of her tears or discomfort. Any time I was confronted with the prospect of long, unbroken hours with my daughter, I ran—literally.

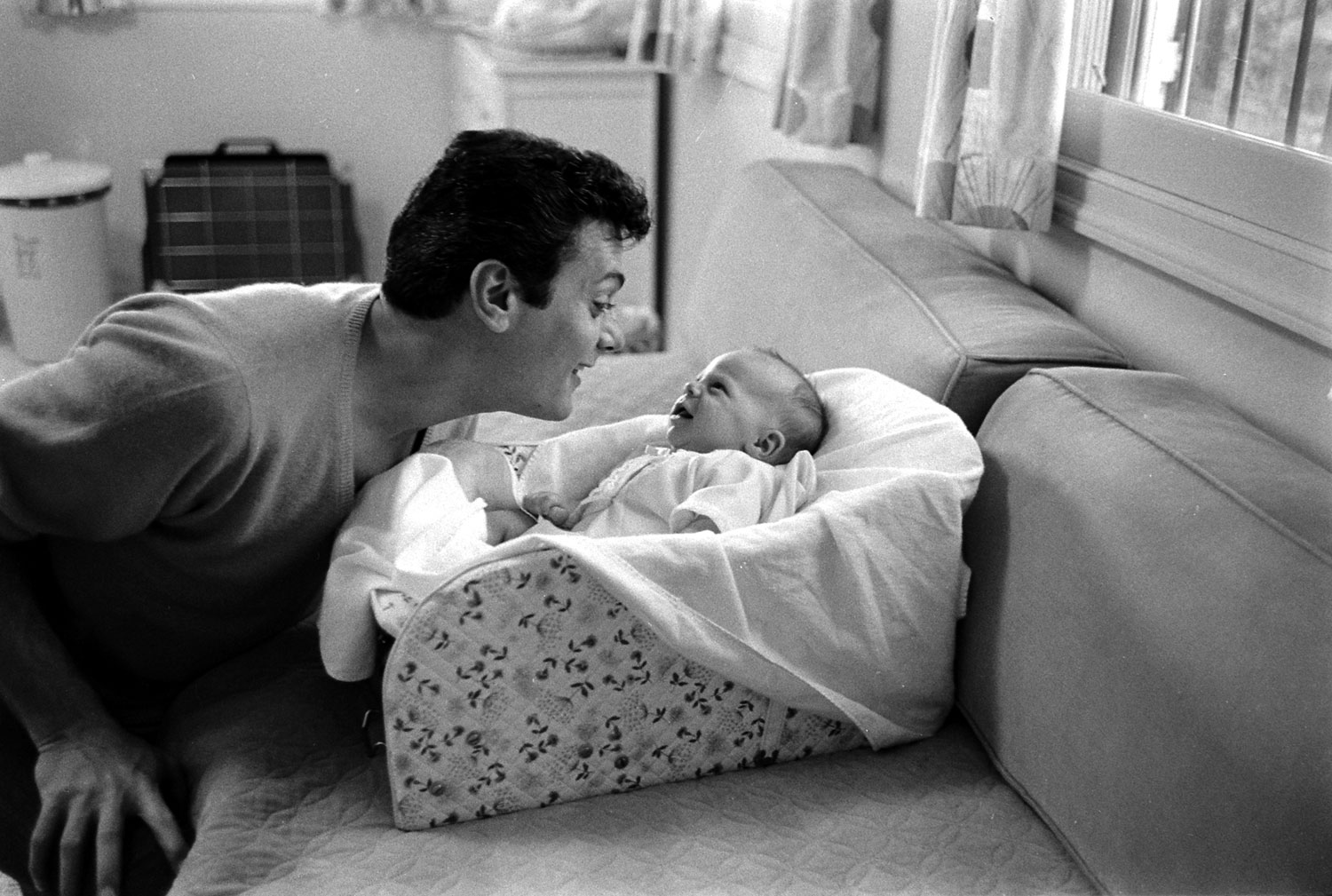

I purchased a little home for us, finally moving out of the apartment I had shared with Katherine. As I slowly joined the living, my own idea of what a father should be started to come into focus. It had little to do with the duties I had originally imagined make a dad: breadwinner, patriarch, roles that my difficult but responsible and loving father played magnificently. My discoveries were much humbler—and in places that my father, with his dashing Old World charm and perfectly coiffed hair, would never set foot in. I loved to take Isabel shopping in the big box stores and push her through the aisles of Target in an elephantine red cart. As I balanced my shopping bags in one hand and hoisted Isabel into her car seat with the other, I felt like more than just her father—I was slowly becoming her dad. The real transition came when my mom moved out of the house, and I began to raise Isabel on my own.

I had imagined that fatherhood meant above all sacrifice, the giving up of the things you love for the one you love, a kind of ascetic affirmation of love in self-denial. How wrong I was. There was nothing of the sense of loss implied by sacrifice, as I slowly organized my days around Isabel’s needs, rather than my own. The love I now felt for my daughter was the most self-satisfying, self-fulfilling I had ever known.

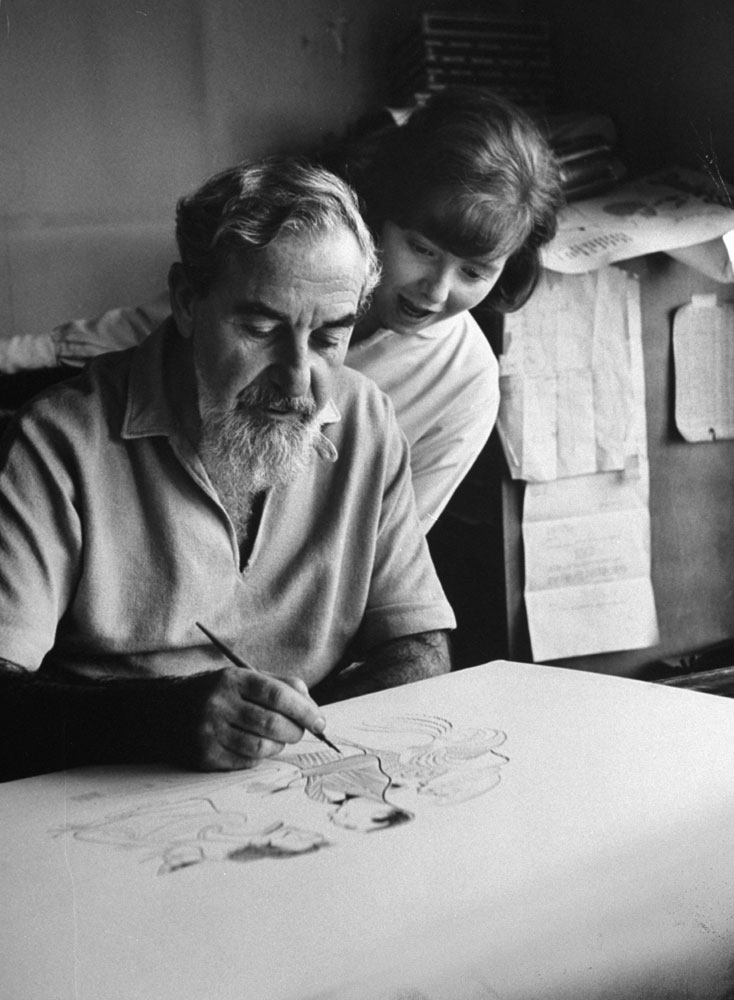

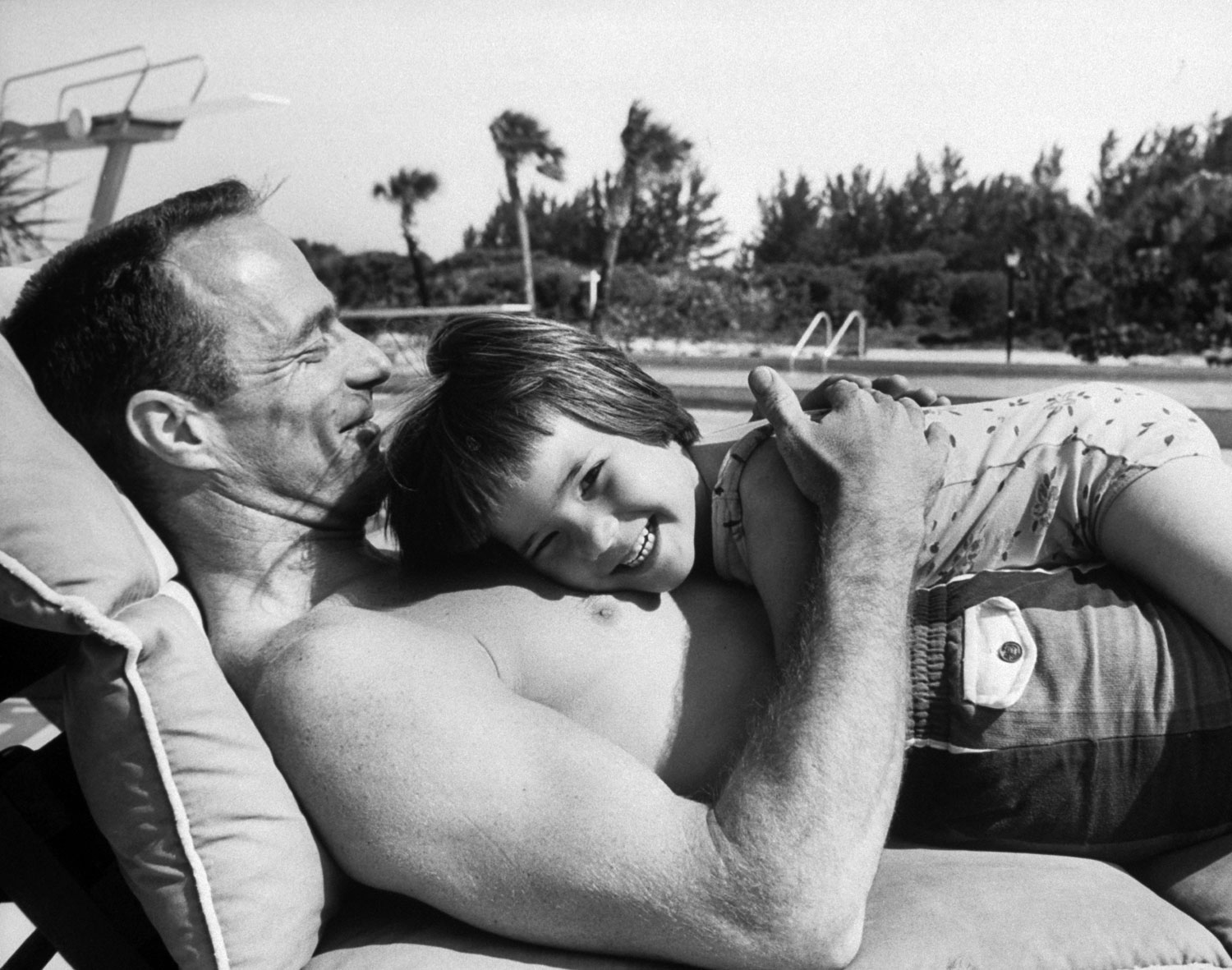

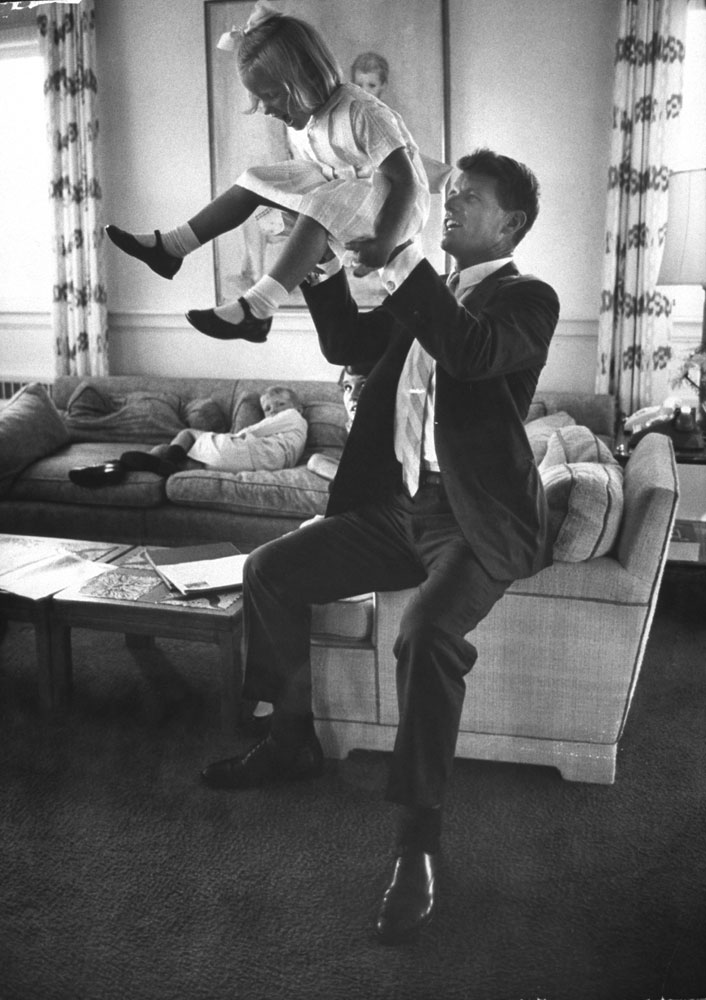

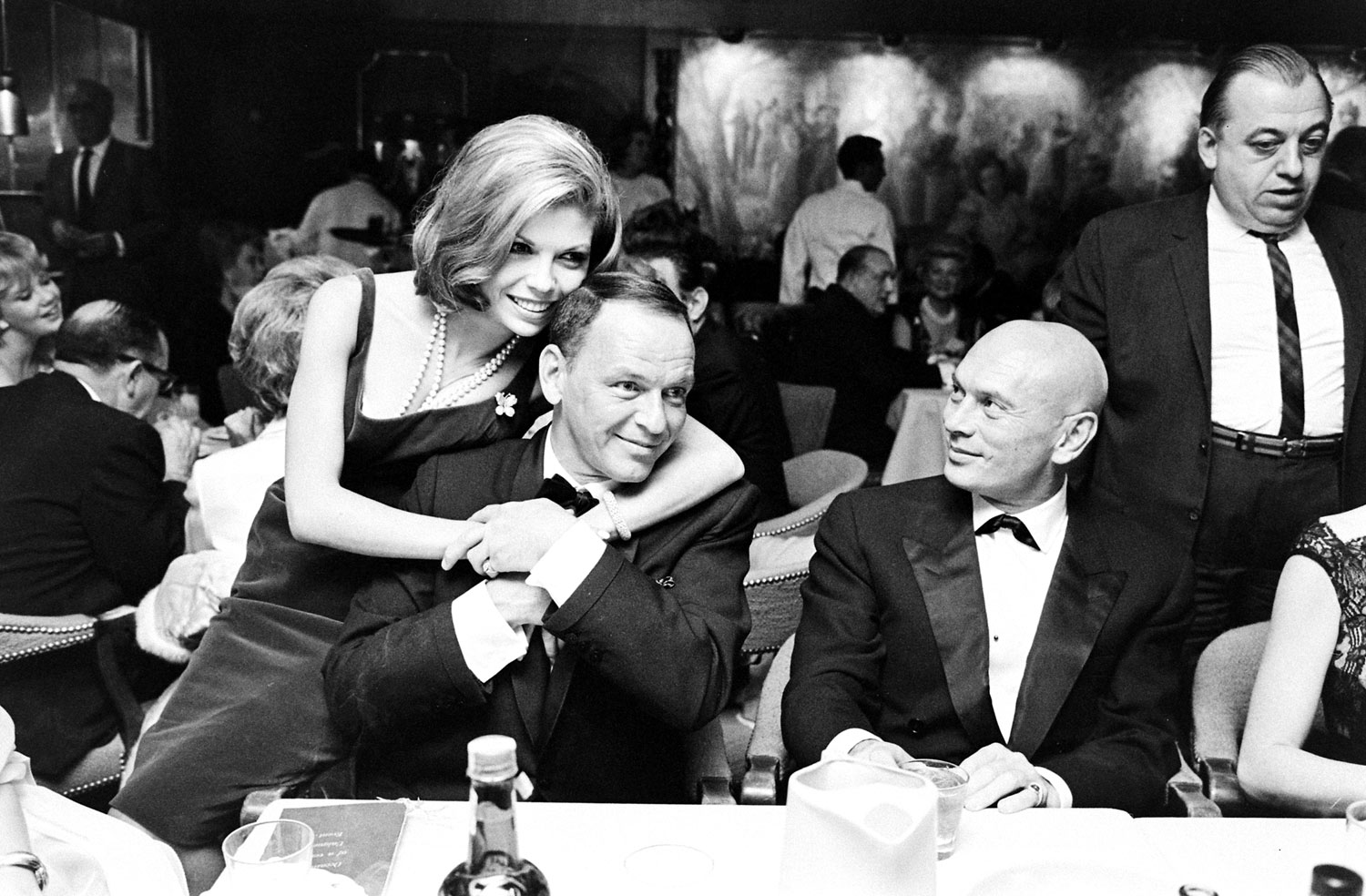

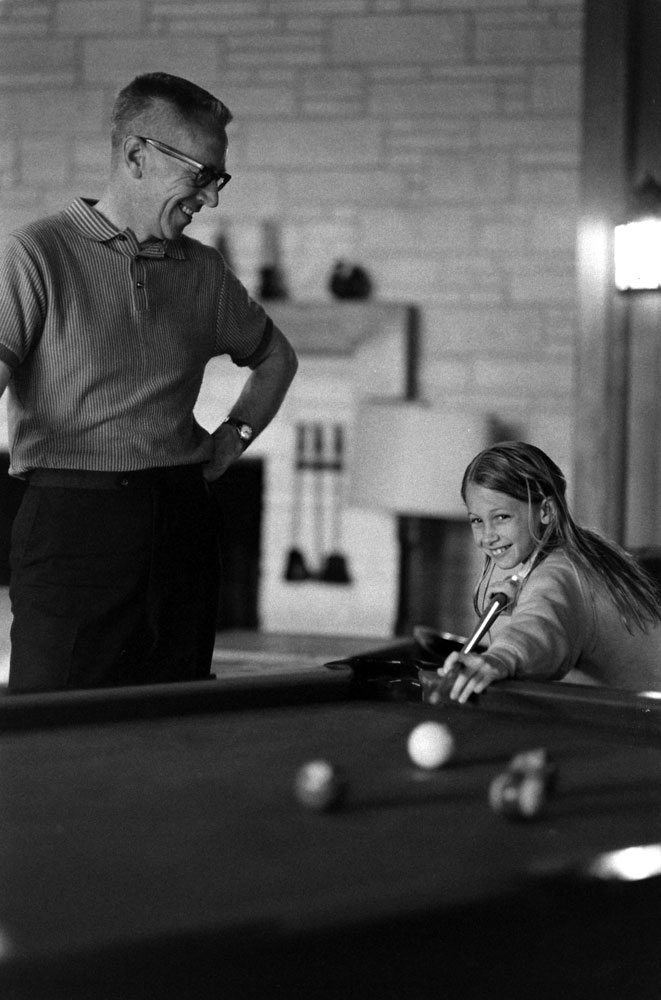

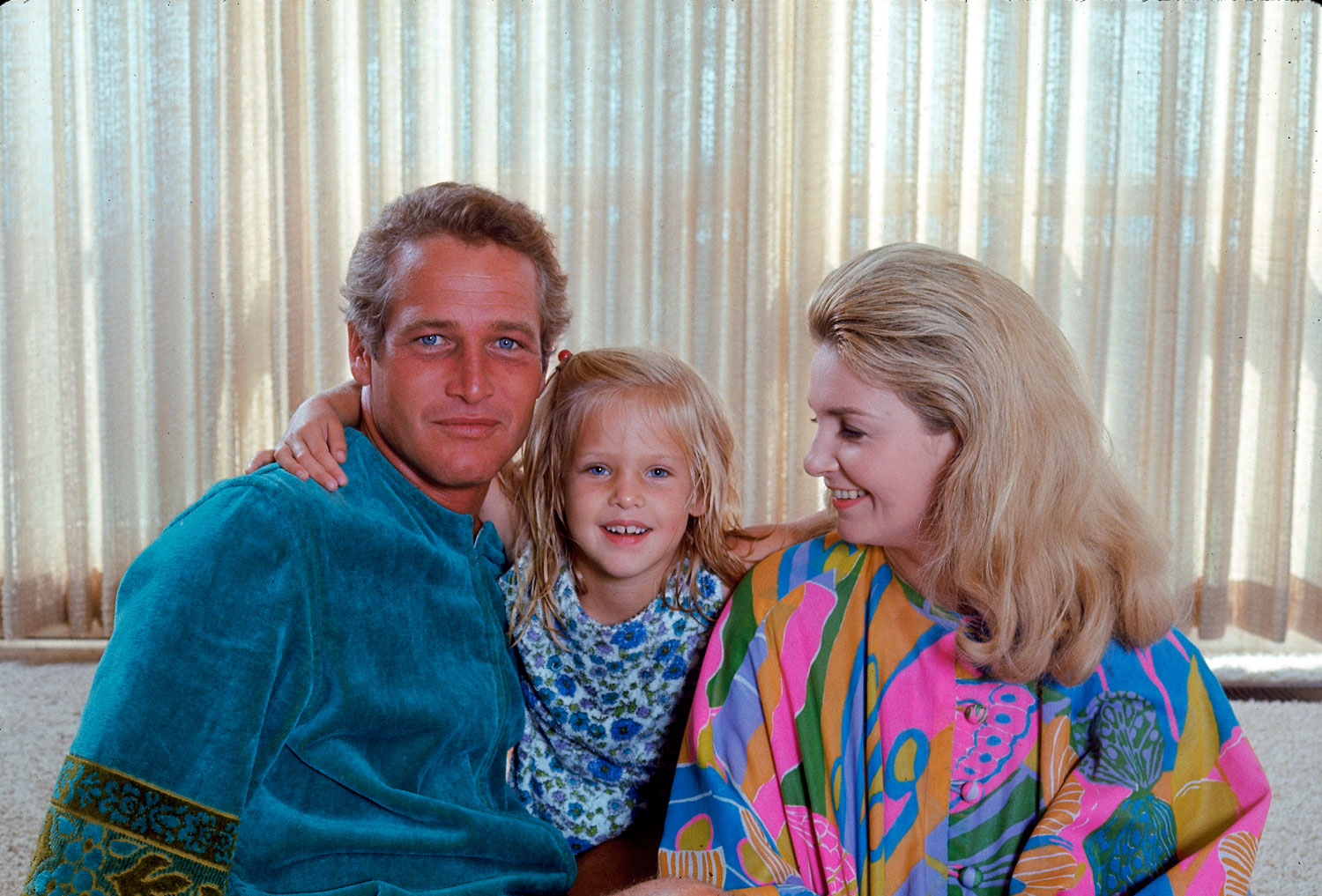

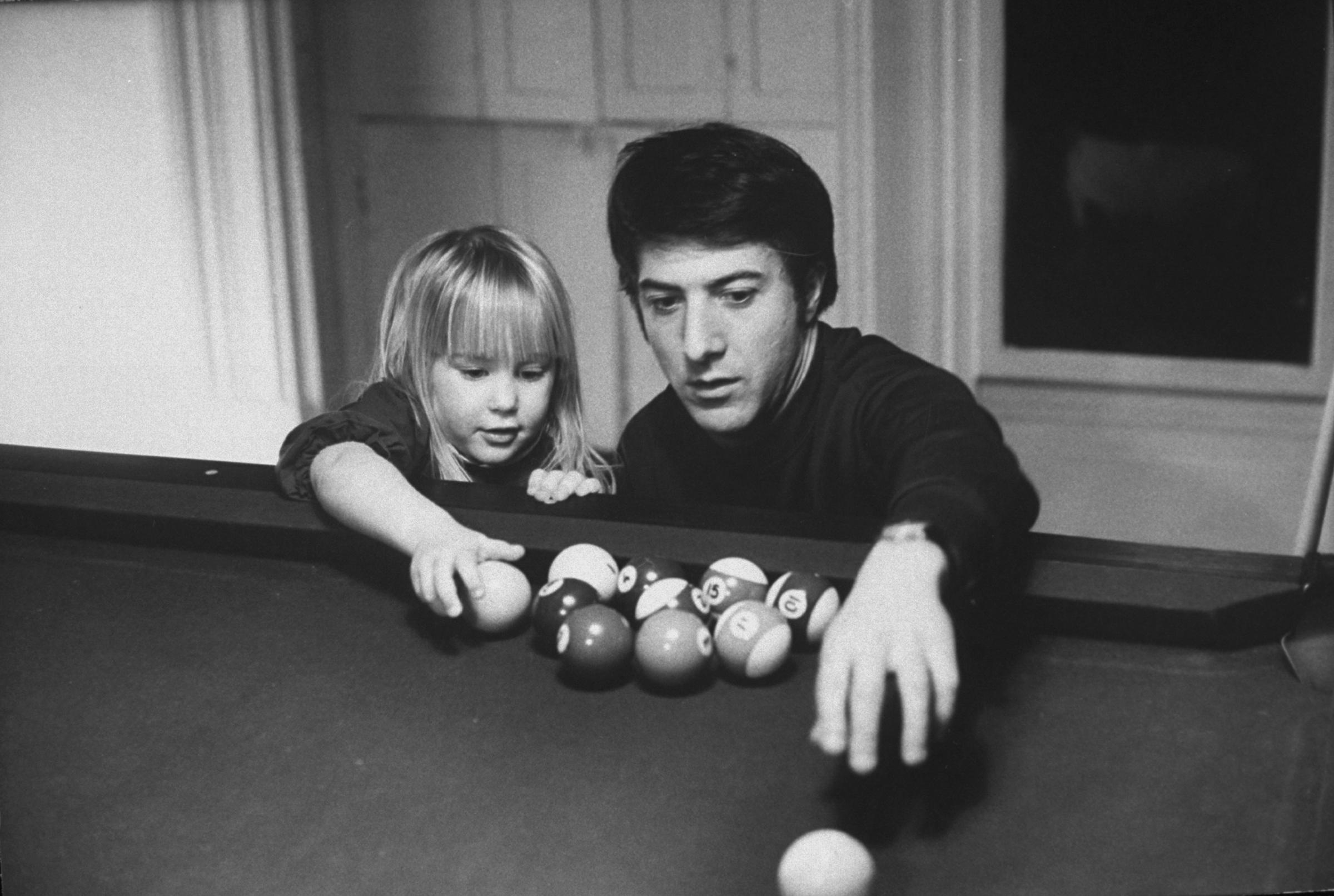

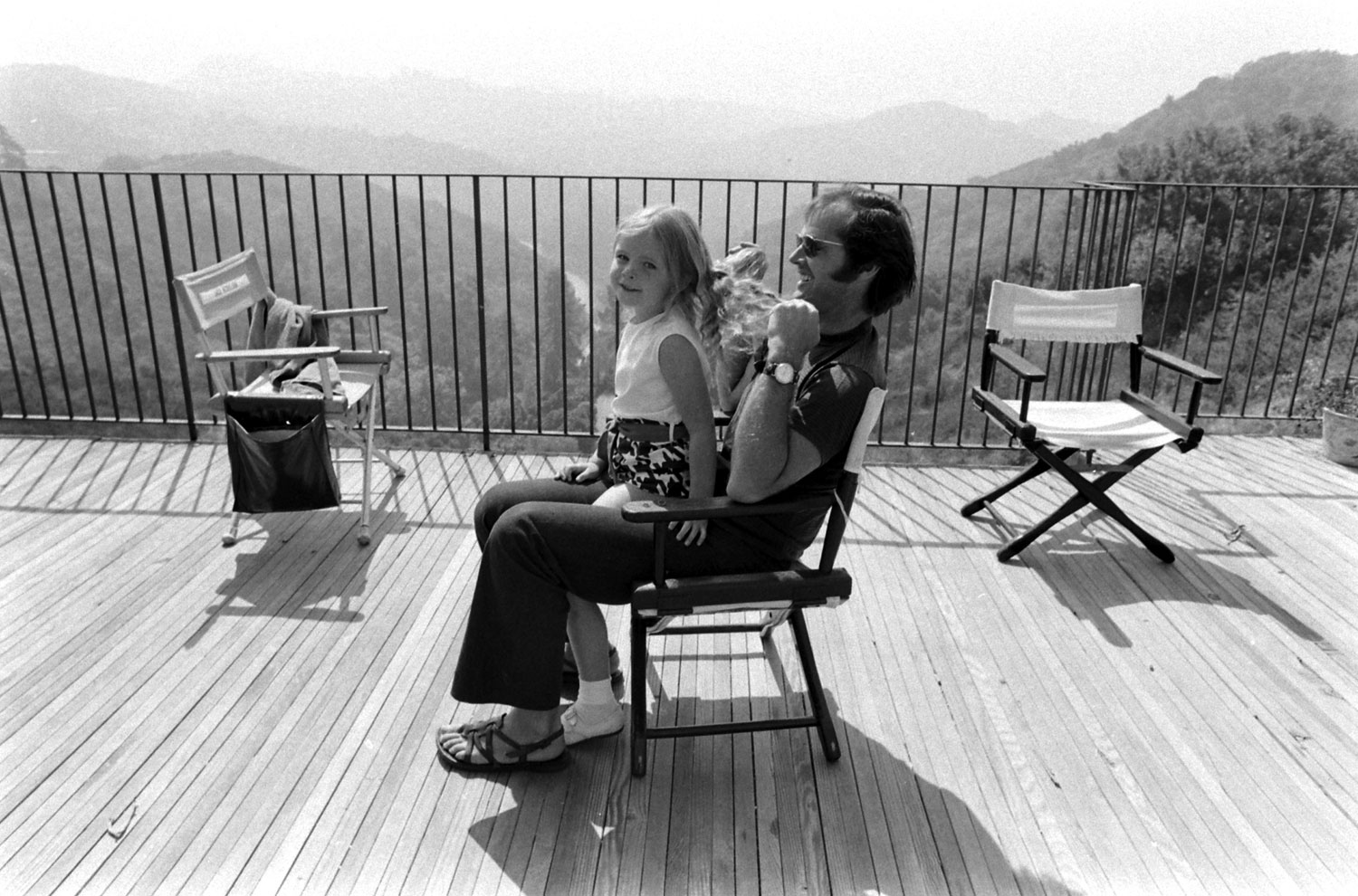

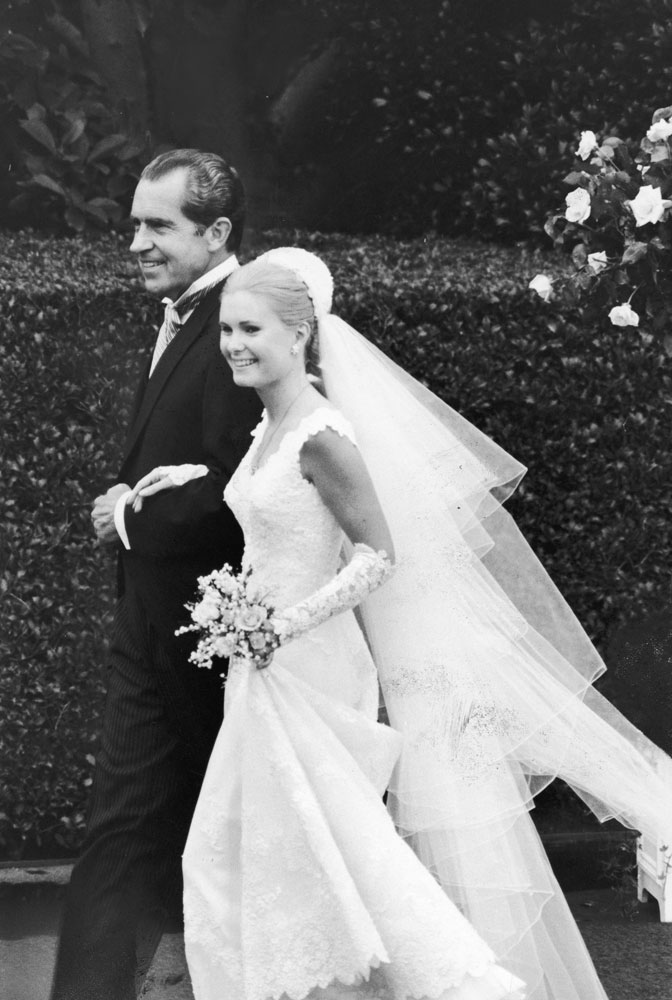

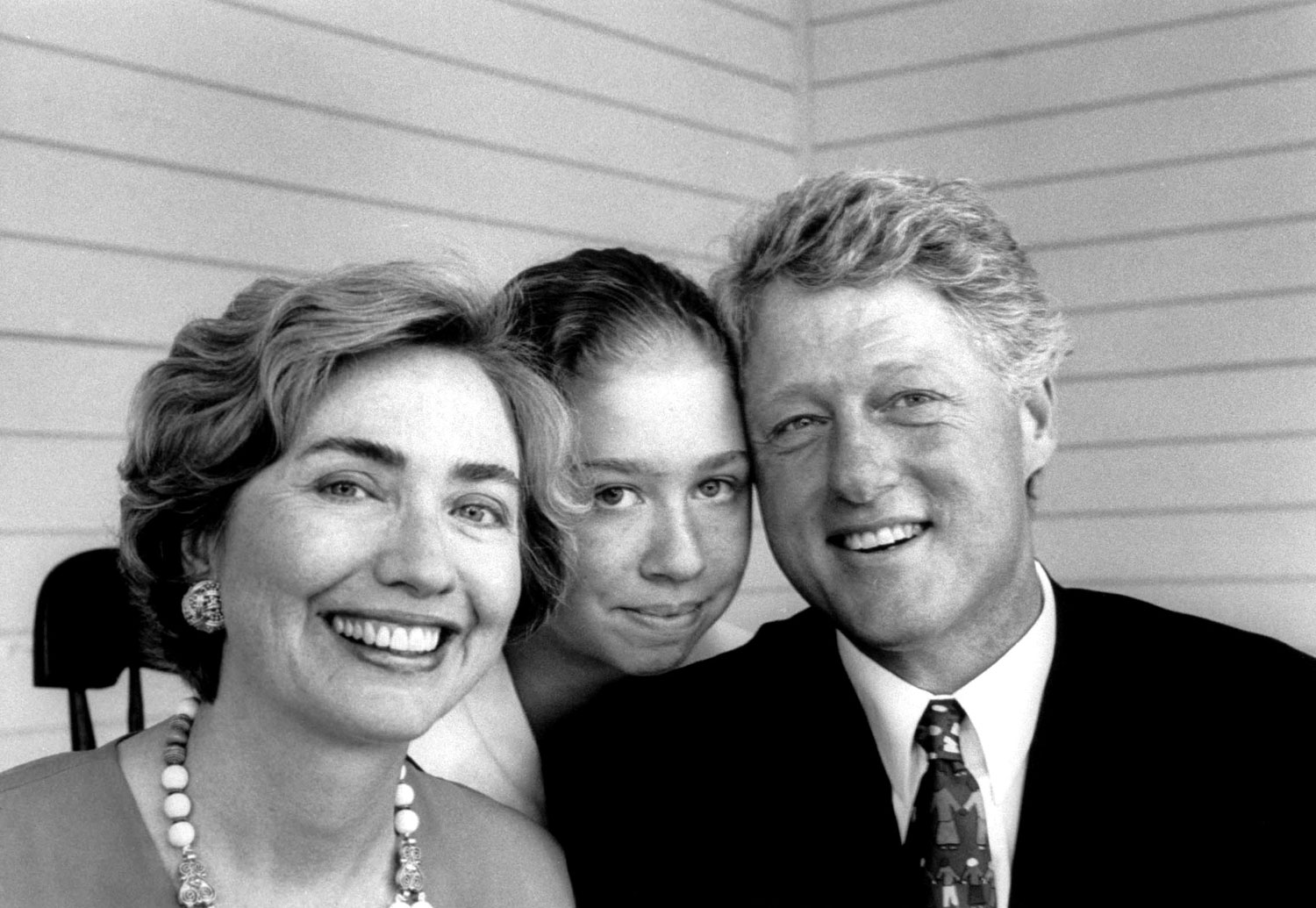

Father's Day Special: LIFE With Famous Dads and Their Daughters

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com