My father loves pills, whether prescription or over-the-counter. Red ones. Pink, blue, yellow, and white ones. Muscle relaxants. Beta-blockers. Blood thinners, stool softeners, and acid reducers. And then there is the kind of sleeping pill he chose from his beloved pharmaceutical cornucopia when he wanted to die one sunny summer Monday—Ambien, a little white sleeping pill no bigger than a Tic-Tac.

When I arrive at the hospital, my father is asleep in the emergency room and looking only a little ashen for a man who has taken what he thought was a dose to help him sleep forever. My brother looks relieved that I’ve come right away.

There isn’t room for two visitors. So he steps away to leave us alone. My father raises his head and opens his eyes for a moment. “Bobby,” he sighs. Then his head falls back to his pillow.

“Hi, Dad. I’m here.” I take his soft, arthritic hand, which I know as well as my own. His wrist is connected to an IV port. Over the emergency room noise — the voices and beeping of machines — he resumes snoring. I look at him and it strikes me hard : He wanted to die because his heart has been making him so weak lately, and we had no idea that his desperation about his failing health had become so intense.

“Do you think he’ll be okay?” I ask a nurse.

“Oh yeah,” she says. You can take a whole bottle of Ambien and it won’t kill you. It’s not that kind of drug.”

I detect a kind of cynical empathy in her voice, if such a thing is possible. Perhaps she is acknowledging what I can’t get out of my thoughts. This fiercely independent eighty-two-year-old fun-loving man, who still drives and plays bridge like a maniac and who doesn’t want to be a bother to his sons has just brought a great deal of bother to us. What are we going to do with him now? Suicide with six pills? What was he thinking? Well, his logic has always been as sloppy as he is. In his car, he still has a hundred tennis balls, a dozen yarmulkes, bridge columns, old sneakers, and X-rays. An ever hopeful man, he keeps a couple of Trojans in the glove compartment too. And next to the driver’s seat he keeps an old Styrofoam cup of his beloved pills. Mostly they’re for allergies, which hit him as hard in spring as they do me. Anytime I would sneeze he would stick his hand in that cup and pull something out for me.

“Dad, those are prescription,” I’d tell him. “Don’t force them on me.”

“Just trying to help,” he’d always say.

Looking at him in the emergency room bed now, I think about the times I’d said no to all his pills and the look of disappointment that darkened his face. Then I think about all the times I said no to all his other requests. He wanted to share a vacation house with me for a month. He wanted to show me the money he and my mother had for me in dozens of savings accounts.

I always said no. Maybe I should have said yes once in a while.

I wonder, Is there a pill a son can take to open his heart to his father?

Later, we join him in a private hospital room upstairs. He’s lying awake over white sheets in a pale blue gown. His smudged aviator glasses sit crooked on his nose. What do you say to someone who has just woken up to find that, against all his wishes, he’s still alive?

“You’re awake,” I chirp.

“Hi, Dad,” my brother follows.

“Nice to see you guys,” Dad says.

Jeff and I exchange looks. Nice to see you guys? As if we’ve come for lunch?

A moment later, a pale, middle-aged man with a ponytail and black clogs walks in: Dr. Jack Downer. The irony of the name makes us raise eyebrows. Dr. Downer gets right to work. Like someone taking a survey, he asks my father the basics—if he knows the day and if he can count backward by sevens. My father, a lover of crossword puzzles and sudokus, scores well and beams from the attention. His mood, verging on buoyant, as if nothing has happened today, is inappropriate at best.

“Have you ever had psychiatric problems, Mr. Morris?” Dr. Downer asks.

“No! Never! And I’ve never been to a therapist either.”

“Did you really intend to die?”

Jeff and I cringe at the question.

“Yes, and I actually chose a Monday to do it because I figured it would be more convenient for my boys and not disturb their weekend plans.”

“I see,” the doctor says.

I wish that Dr. Downer weren’t quite so true to his name and could be a little more uplifting. He doesn’t sit, but rather stands as far from the bed as possible.

“When you woke up from your attempt were you glad to be alive?”

My father doesn’t say anything. He pushes white strands of hair from his smooth olive skinned forehead so much like mine, and we wait for his response. This is what he so wanted to avoid, a prolonged ending on a low note after a life of breaking into song with the slightest provocation, reveling in talking to strangers, from waitresses to toll booth collectors (much to my constant consternation), tossing tennis balls and old rackets to children in municipal parks, pouring orange juice and raspberry sweetener onto everything and generally being an out of control sticky mess of affability whose heart is as big as it is damaged.

“Well, I was prepared to live,” my father finally answers. “I wasn’t sure the pills would work.” The doctor makes a note. Then he tells my father he will have to be moved to a locked psychiatric ward for observation tomorrow. It’s the law in New York State.

“I’d really appreciate it, Doc, if I could spend the night in this bed and then just go home in the morning and forget this whole thing,” he says.

“I don’t think that’s possible,” Dr. Downer says.

“Why not? I made a mistake, and I won’t do it again.”

“But do you still want to die, Mr. Morris?”

My father looks over at me and then at my brother. We lean in toward him from our chairs, helpless. It feels as if the entire hospital has gone silent. We wait for his answer.

“No, but I still would like to put an end to becoming dependent on others,” he says.

Dr. Downer leans against a ledge and softens his tone. Behind him, a Pepto-Bismol-pink sky illuminates his long, bristly hair.

“Aren’t there things you do that you can enjoy on your own?” he asks.

“Not really. To be honest, I’m out of plans.”

“Well that’s not very reassuring, Mr. Morris.”

My father sighs. I feel frustrated for him, knowing he’s trapped and that he will have to pay for the mistake of not finishing himself off properly, which turns out to be common with the suicidal. They don’t drown as they’d intended, or they throw up the pills they take. Or someone finds them just in the nick of time, and by saving them ruins their careful exit strategy.

The interview is winding down. But Dad, desperate to keep playing the host and keep the conversation going, wants to be reminded of his interrogator’s name.

“It’s Dr. Jack Downer, Mr. Morris,” the doctor says.

“So is there a Jill for you, Jack?” my father, the habitual matchmaker, asks.

“What do you mean?”

“You know—so that a Jack and a Jill can go up the hill to fetch a pail of water?”

My brother turns red. I smile, then keep my smile from widening, as I often have to around such an uncontrollable well-meaning yenta of a father.

“No, there isn’t,” says the doctor with his head now cocked to one side. “Why?”

“Because I’m going to fix you up,” my father says. “That’s what I like to do.”

The doctor steps forward to stare like an ornithologist inspecting a rare species of bird. My brother and I look away to hide our laughter. The father we find so amusing and embarrassing has returned to us for a moment, and we are overjoyed to see him.

“That’s a funny thing to suggest to a doctor you just met,” Dr. Downer says. Then, after a long pause, the trace of a smile crosses his face. “But I’m open to it.”

“Doc,” my father says, “you just gave me a very good reason to live.”

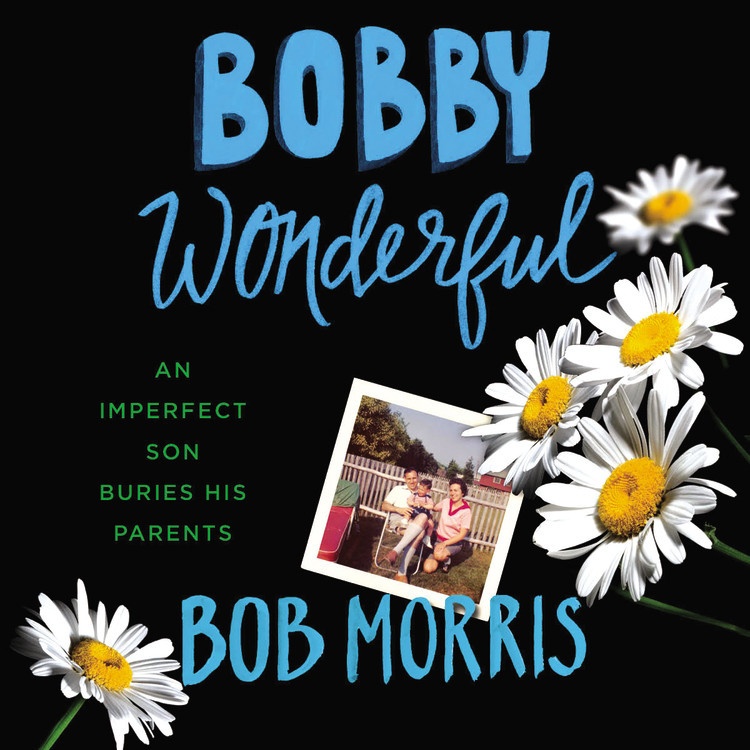

From the book BOBBY WONDERFUL: An Imperfect Son Buries His Parents. Copyright (c) 2015 by Bob Morris. Reprinted by permission of Twelve/Hachette Book Group, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com