Terry Virts knows he’s lucky. The American astronaut recently returned from nearly seven months on the International Space Station, his second trip to space, which ended up lasting longer than expected.

Virts, along with Russian cosmonaut Anton Shkaplerov and Italian astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti, was forced to stay board the Space Station for an additional month after an arriving Russian cargo vessel malfunctioned in April and later burned up in the atmosphere.

During their 199 days in space, they conducted hundreds of scientific experiments and went on three spacewalks. Back on the ground after his return on June 11, Virts discussed, in an exclusive interview with TIME, his extended stay in space and where he finds the time to photograph the Earth amid a packed schedule.

“I was ready to stay up there because there were still pictures I wanted to take, there were still videos I wanted to do,” he says. “If you’re an astronaut flying in space, you gotta look at that as your last flight. And so you gotta enjoy it. And I’ve got the rest of my life to be on Earth.”

Virts, 47, is a Maryland native with a wife and two children. He was selected as a NASA pilot in 2000 and began training shortly afterward. This trip to space ended up some 15 times longer than his first, a 13-day mission on space shuttle Endeavour in 2010, and gave him more opportunities to show the rest of us what he sees.

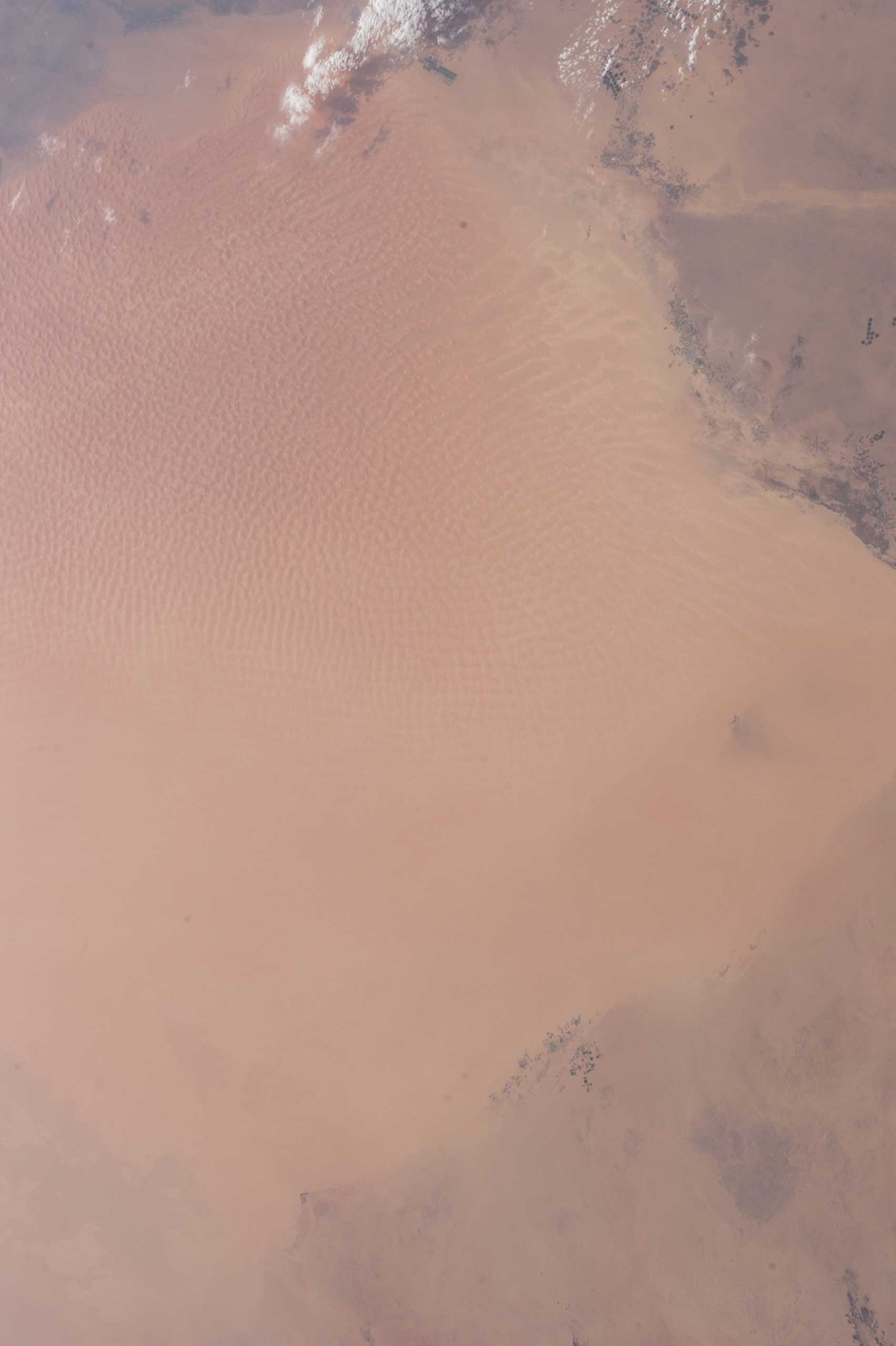

Throughout his stay aboard the Space Station—he traveled about 84 million miles since last November—Virts was shooting stills and videos that were later posted to Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Vine with support from his colleagues on the ground. He captured lightning storms over the Himalayas, Mexico and the American heartland; overhead shots of the ice fields of Patagonia and painterly farms of central Brazil—all images that showed the natural beauty of the planet. On his last day, he finally managed to get a shot of the pyramids in Giza, Egypt.

It all helps him connect with Earth, he says, describing a need to document what he sees and share it with others. “It’s just part of my personality and part of what I want to do. And it’s a challenge.”

That’s an understatement.

The Space Station orbits the Earth 16 times each day, at 17,500 mph. “Things go by so fast, or you look on—we have these computer maps where it shows where we are over the Earth—and you’re like, ‘Man, I just missed that target,’” he says.

Other things can get in the way, too. The desired target could be too far in the distance, or maybe there’s weather above it, or perhaps the pass is in the middle of sleep or work. Beyond the technical aspect, there’s an artistic one, too: “Does it capture the feeling, and the emotion, in the sense of what you’re seeing? That’s a bigger challenge—the one that I like and the one that you just can’t do,” he tells TIME.

One thing that was visible from space, Virts notes, is wealth around the world, evident by city lights at night. “At nighttime obviously, cities make you feel connected there. I think more than connected, it makes you learn about Earth,” he says. “You can really tell what economies are doing well.”

Central Europe, from England to about Poland, for example, is “just completely bright,” he says. In the sparsely populated Russian lands east of Moscow, “there’s not a lot of lights.” Cairo is “super bright” and there are “really bright European-looking cities” in South Africa, but otherwise, he says, “the whole continent in between is mostly dark, with just little orange dots here and there.”

Still, the most stark contrast—“it’s literally night and day,” he says—is North and South Korea. “There’s all this bright economic activity,” around Beijing, Tokyo and Seoul, “and then there is a black hole with one very small white dot, and that’s Pyongyang.”

His time in space has afforded him the chance to learn to associate colors with different places on Earth. “I have a new sense of the different continents and countries on Earth than I did before,” he says. “You learn, you feel this connection with different places on Earth by what you see in space.”

When he thinks of Australia, for example, he thinks of red. “The outback is really red, it’s amazingly red,” Virts says. India and the jungles of central Africa are “hazy.” Beijing and Shanghai, the Chinese megacities, are “just brown,” due to pollution. Russia during the winter is “thousands and thousands of miles of white,” and the Bahamas are green and turquoise. “I want to go there,” he says, noting that his travel bucket list got much bigger.

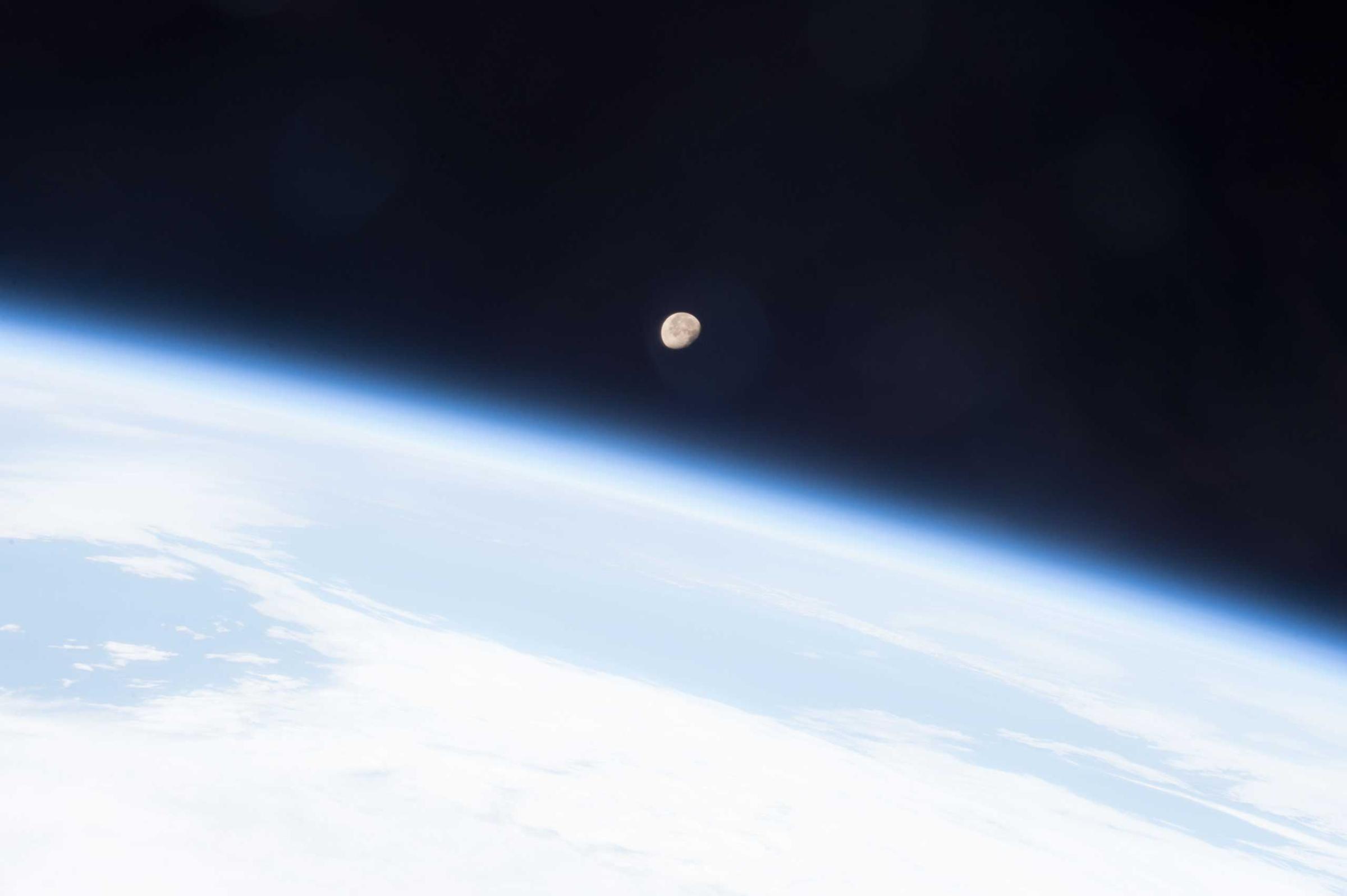

Sunrises, “were always one of my favorite things,” he adds. “I saw colors that I had never seen before.” He describes the distinct bands that he could see looking down on the atmosphere, ones that our eyes can’t see from the ground. “Trying to capture those with a camera is really tough.” Virts experimented with the burst mode and “a lot of different shutter speeds and apertures to try and get the colors.” Still, he says, “I never found a picture that captured everything that the eye saw.”

As the interview wrapped up, Virts recalls a story by a friend. A fellow astronaut, Mike Fincke was asked before a space launch about his favorite planet. “Is it Mars? Is it Jupiter?” Fincke was asked. “And when he came back from his Space Station mission, he said, ‘My favorite planet is Earth.’”

“There’s definitely no place like this in the universe,” Virts says, “that’s for sure.”

Interview by Shaul Schwarz and Jonathan Woods. See the trailer of A Year in Space, a multi-part documentary series produced by TIME’s Red Border Films and directed by Shaul Schwarz and Marco Grob.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com