On a sticky summer day in a midtown Manhattan studio, country singer Kacey Musgraves, 26, was rehearsing for a performance on Late Night With Seth Meyers. The night before, she performed her new single “Biscuits” to a rapturous crowd on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, but for Meyers she was unveiling a brand-new song, “Family Is Family.” The chorus goes like this: “Family is family, in church or in prison/You get what you get and you don’t get to pick ’em/They might smoke like chimneys but give you their kidneys/Yeah friends come in handy but family is family.”

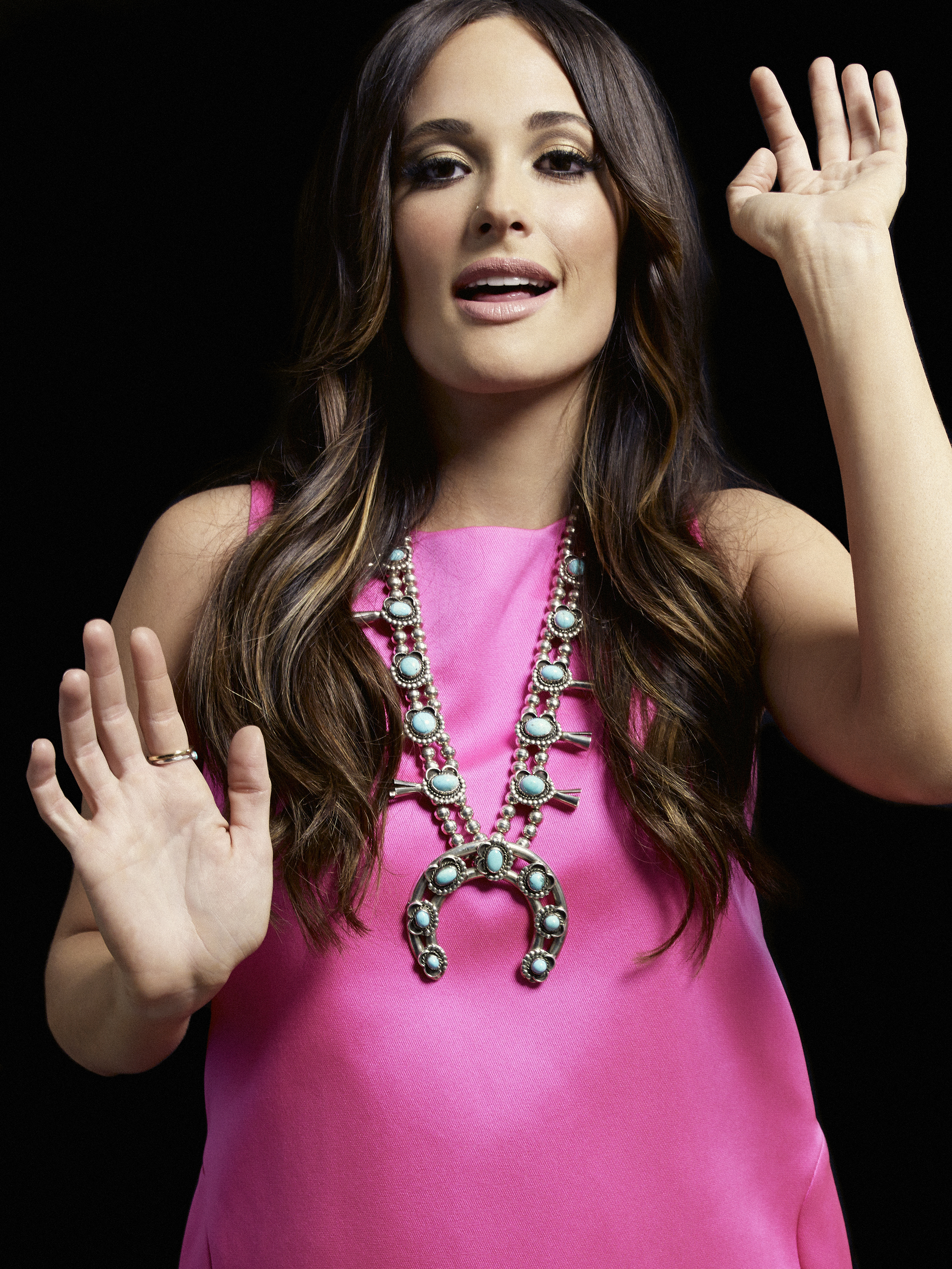

Musgraves sang these lyrics with gusto, over a twangy, syncopated beat, in what sounded like one impossibly long breath. She wore a guitar on a glittery strap, a garish statement necklace, bell-bottom pants and several cans’ worth of hair spray. The stage was dressed like a tacky ’70s prom, streaked in purple and gold. For a moment, the effect was transporting, like being whisked away to a dusty Western saloon as imagined by John Waters–a trailer-park cabaret. Then she stopped. “Can I get some more steel?” she said, suddenly businesslike, wanting to hear more steel guitar in her monitors. A makeup artist, in a studded black leather jacket, flitted to her side for a touch-up; a hairstylist followed. Production assistants scuttled at her feet.

New York isn’t really Musgraves’ scene; nor is being on TV, though she’s good at it. She was mostly excited to get back to Nashville, where she lives, to celebrate the release of her new album, Pageant Material, out June 23. “My album-release party is next week,” she says. “We’re having drag queens perform the record, pageant-style.” I ask whether they’re going to be in drag as her. “No,” she says, giving a quizzical look. “They’re just going to be themselves.”

That’s what Musgraves is all about, if you had to boil it down–folks just being themselves, gay or straight, stoned or sober. She’s earned a cult following for being at once deeply nostalgic in her traditional country sound and radically forward-thinking in her witty, offhandedly political lyrics. Raised in Golden, Texas, a tiny town best known for its annual Sweet Potato Festival, Musgraves says she grew up fascinated by the idiosyncrasies of small-town life. “In a big city, you can get away with being a total a–hole,” she says. “In a small town, you don’t have that luxury.”

She self-released three albums and competed on the USA talent series Nashville Star, placing seventh, before signing to Mercury Nashville in 2012. The next year, she released her major-label debut, Same Trailer Different Park, a tight set of airily produced, sharply drawn throwback country tunes penned with top Nashville songwriters Luke Laird and Shane McAnally.

Her breakthrough single, “Merry Go ‘Round,” was so warm and catchy you could almost miss how subversive it was: a withering depiction of the small-town America that most country songs revere. (Sample lyric: “Mama’s hooked on Mary Kay/Brother’s hooked on Mary Jane/And Daddy’s hooked on Mary two doors down.”) Despite the song’s weary tone, it landed in the Top 20 of the country charts and cracked Billboard’s pop chart, the Hot 100. “People who do live in small towns celebrate the honesty about it,” Musgraves says of her songwriting. Another song, “Follow Your Arrow,” urged listeners to “make lots of noise and kiss lots of boys/Or kiss lots of girls if that’s something you’re into,” then advocated that they “roll up a joint–or don’t.”

“As much as it may not coincide with traditional themes, country’s always been about real life–real people,” Musgraves says. “These are things that every single person in America is dealing with. Why wouldn’t I want to write about life?”

At the 2014 Grammys, “Merry Go ‘Round” took the award for Best Country Song. Later in the night, when Same Trailer won Best Country Album, the camera panned to Taylor Swift, who was also nominated. Swift, more amused than disappointed, turned and mouthed to a friend, “I told you.” That summer, Willie Nelson invited Musgraves to open several shows on his tour. (He gave her a joint as a souvenir; she had it framed.) She was also asked to join Katy Perry’s summer tour, and the two ended up taping a CMT special together. It’s a testament to Musgraves’ ability to cross genres–and generations–that she could so easily play both crowds. “She’s like the hipster country al-Jazeera,” Perry says. “She’s an authentic, colorful songwriter. She writes daringly about her experiences. She digs deep for stories, and it’s paying off.”

Country music has long been a bastion of conservative politics. When Dixie Chicks vocalist Natalie Maines made derogatory comments about George W. Bush in 2003, it effectively ended the band’s arc as country stars. Issues like gay marriage might serve as fodder for mainstream radio in songs like Macklemore & Ryan Lewis’ LGBT anthem “Same Love,” but country has grown more risk-averse still. Artists like Florida Georgia Line and Luke Bryan have been lambasted for launching what’s known as “bro-country”–slick tunes that are all about hot girls, pickup trucks and beer, themes unlikely to cause much stir among red-state listeners.

It’s tempting to read Musgraves’ popularity as a backlash to the increasing ubiquity of those artists, to whom she stands in stark opposition. Her choruses aren’t arena-size, and though her melodies are catchy, her songs are more old-fashioned than cutting-edge–too rootsy for pop radio. Her visual style evokes Dolly Parton in its rough-around-the-edges kitsch rather than the smooth theatrics of Faith Hill and Shania Twain. Musgraves cites Glen Campbell and Ronnie Milsap as sources of inspiration, though she says she owes an aesthetic debt to Nancy Sinatra. “Once I figured out that I could use my traditional country influences to do something different,” she says, “I felt like that was the coolest thing I could do. Everyone is doing the opposite of that.”

Yet while the sound of Pageant Material looks backward, the lyrics feel thoroughly modern in both subject and sentiment. The opening track, “High Time,” is an ode to cannabis consumption; lead single “Biscuits” reinforces the laissez-faire politics of “Follow Your Arrow” by suggesting that people “mind their own biscuits and life will be gravy”; the title track takes on the beauty-industrial complex, with Musgraves offering, “It ain’t that I don’t care about world peace/But I don’t see how I can fix it in a swimsuit on a stage.”

Still, her reach never exceeds her grasp–she sticks to what she knows best, taking down the insularity of small-town life on “This Town” and music-industry nepotism on “Good Ol’ Boys Club.” Musgraves nails what the bro-country crop ignores: smoking pot and interacting with gay people are no longer strictly the domain of blue-state liberals. Country music–the soundtrack for the heartland–can celebrate those themes as freely as it always has God, guns and country.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing is just how warm Musgraves’ reception has been. Calling her controversial, she says, is just media spin. “It’s funny that it’s been made such a talking point,” she says. “I believe people should do what they want with their own bodies. That’s not very progressive to me. These issues–if you watch the news, they’re becoming legal. The majority of the younger people that listen to my music don’t think twice about the things that I’m singing about.”

As for the ones who do, Musgraves is perfectly content for them to mind their own biscuits too. “It’s not meant to resonate with every single person in America,” she says. “This isn’t a telemarketing campaign. It’s fine if you don’t like it, but it’s made a lot of people walk a little taller.” She thinks on it for a moment. “Or change their mind about country music.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com