The Yellow King is gone. Matthew McConaughey and his Nietzschean monologues are gone. The Louisiana backwoods setting is gone, as is director Cary Fukunaga, who wove a haunting nightmarescape out of the bayou steam. What’s left, in True Detective season 2 (premieres June 21 on HBO) is creator-writer Nic Pizzolatto telling another hard-boiled—now twice-boiled—story of hard men, broken men and angry women (well, one woman, anyway).

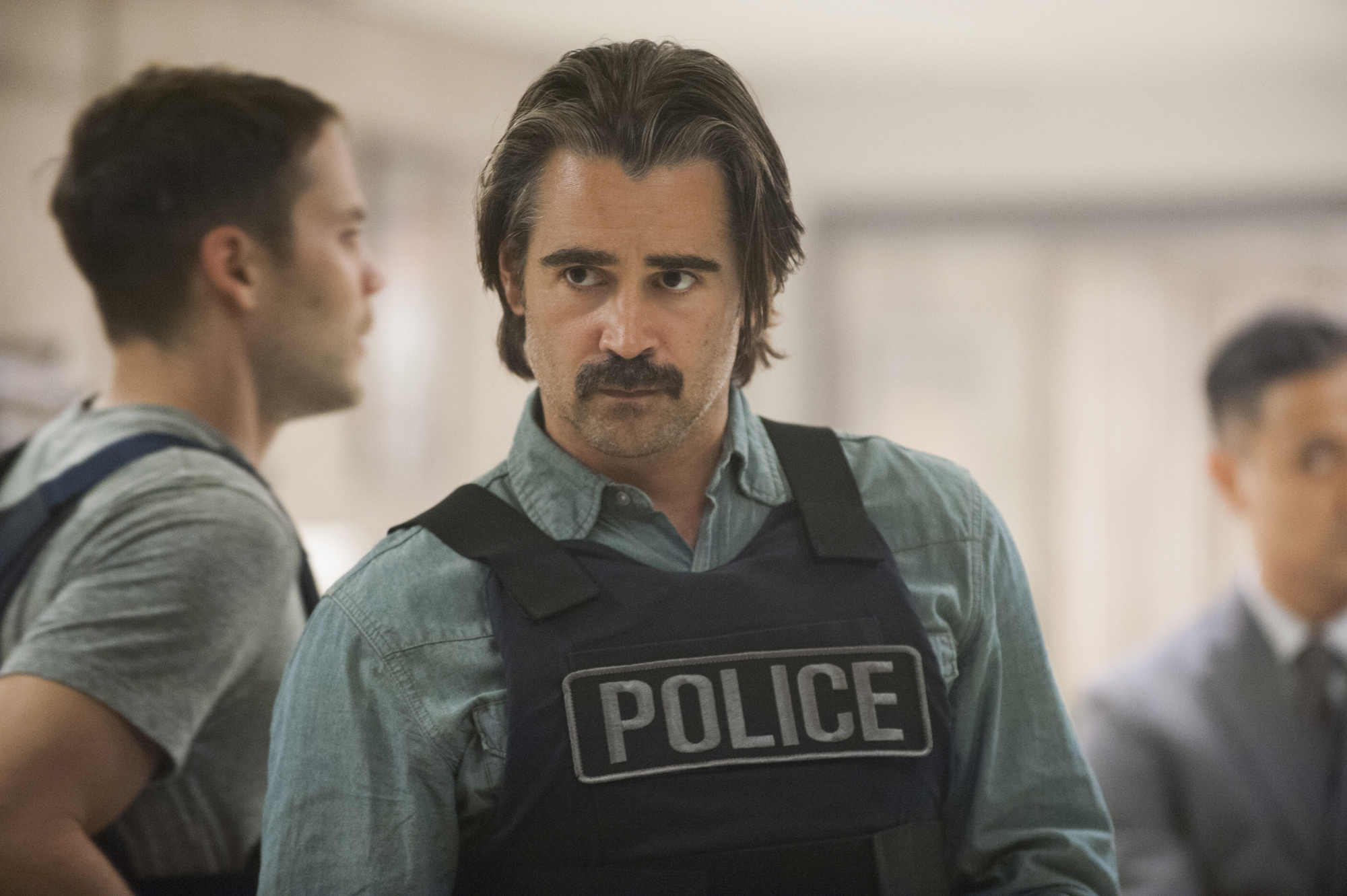

The new season deposits us in tiny Vinci, Calif., less a town than a scam, a haven for sweatshop owners and a goldmine for corrupt city officials. Its symbol is Ray Velcoro (Colin Farrell), a whiskey-brined cop whose mustache droops like a flag of surrender. His decline started years ago when his wife was raped; his thirst for vengeance ended his marriage (he’s now fighting for custody of a son who may not be his biological child) and put him in hock to mob-tied businessman Frank Semyon (Vince Vaughn). When a bureaucrat working to grease a high-speed-rail contract for Frank is found grotesquely murdered, Ray’s bosses and his patron want him to handle the case–though not necessarily to solve it.

But competing jurisdictions saddle Ray with unwanted partners: Ani Bezzerides (Rachel McAdams), a scrupulous sheriff’s detective with anger issues from her hippie childhood, and Paul Woodrugh (Taylor Kitsch), a highway motorcycle cop with anger issues from a stint as a mercenary in Iraq. She’s anguished, he’s anguished—there’s so much showy pain here that Pizzolatto seems to be re-creating Darkness at Noon, the grim-cable-drama parody from The Good Wife.

The first True Detective had flaws—thinly drawn rural and female supporting characters, for instance—but its verbal confidence and visual audacity made it unmissable.It was a literary experiment pretending to be a crime drama, an attempt to gene-splice Faulkner, Chandler and Lovecraft into a beast that Pizzolatto and Fukunaga then loosed into the wilderness. The creature got away from them at times, and in the end its trail led to a finale that was half-sentimental, half-freakshow, but the hunt was surprising and exhilarating. True Detective might not have been much of a detective story per se, but that was all right as long as Pizzolatto–like Paul Auster and others before him–used the noir genre to smuggle an existentialist investigation of being onto his story.

Season 2 (HBO screened three episodes for critics) loses the novelty of the show’s first outing and highlights the weaknesses. A crew of new directors create a more intimate but more TV-conventional look, as Pizzolatto leads his cops past a parade of vacant sex workers, greasy pimps and blowsy dames. And where Louisiana made fertile and unusual ground for a noir story, both the setting and the dialogue this time around feel much more familiar. The original’s road-trip bull sessions and cat-and-mouse interrogations are replaced with clipped lines that play like poster copy: “I welcome judgment.” “Never do anything out of hunger.” “Everybody gets touched.”

The first season of True Detective was criticized deservedly for its female characters; its best defense–that everyone except Rust and Marty was two-dimensional, including its male villains and hypocritical holy rollers–was true but insufficient. Season two makes some cosmetic changes: the opening credits retain their silhouette design, but lose the “closeups of female asses” that Emily Nussbaum targeted in her New Yorker takedown of the show in favor of landscapes and abstractions. (There’s also a new theme song, Leonard Cohen’s deadpan “Never Mind.”) And in a kind of answer to Marty and Rust’s long roadtrip dialogues, Ray and Ani discuss why she carries knives. “The fundamental difference between the sexes,” she says, “is one of them can kill the other with their bare hands. A man of any size lays hands on me, he’s going to bleed out in under a minute.”

“Well, so you know,” he answers, “I support feminism. Mostly by having body image issues.”

But we’re still seeing a lot of women characterized through sex: hookers, horny girlfriends and kept women; a Hollywood starlet who offers Paul quid pro quo to get out of a traffic stop; Ani’s sister, a webcam performer whose workplace Ani busts in an attempt to rescue her (though she doesn’t want rescuing). In fairness, True Detective was, and is, about broken people, both male and female. But it has distinct, stereotypical ideas about the different ways that men and women break.

Arguably, these are stereotypes meant to show men in the worse light–“A good woman mitigates our baser tendencies,” Frank says (and he has an enabling wife to prove it)–but they’re stereotypes all the same. For True Detective‘s women, femininity is a burden and a weapon. (At one point Ani’s female superior tells her to use her sexuality to get leverage over Ray: “He’s a man, for chrissake. I’m not saying f*ck him, but maybe let him think you might f*ck him.”) For the show’s raging bulls, masculinity is an ideal and a diagnosis.

The season’s lengthy casting search does pay off, mostly. Farrell—functionally the show’s lead even if it’s presented as an ensemble—lets slip the hint of a better man under his sheath of bitterness and hair grease. His scenes with his insecure, bullied son are especially terrific. Ray’s love is so febrile that it boils over, even as he knows that he’s making things worse for everyone. He’s painfully aware of his failings as a husband, father, cop–”I’ve never been Columbo”–but he doesn’t know any other way than to steer into the skid.

McAdams is intense but less well-written for, in a role defined mainly by being “angry at the entire world, and men in particular,” as her guru father (David Morse) tells her. Vaughn, though, can’t sell his semi-made man, coming off peevish instead of raging. As for Kitsch, he does his best in a role that, early on, largely asks him to seethe under the burden of a deep inner secrets–I won’t spoil, but the hints start dropping quickly–while carrying an un-turn-offable lady magnet in his pants.

This could have been better, and might be yet. (Though three episodes is a substantial taste, the three-act structure of the first series showed that True Detective reserved the right to change without warning.) The setup of three cops with three agendas investigating the same case has strong possibilities, and there’s a Chinatown potential in the premise of turning California infrastructure into gold, if the series could transmute its leaden angst.

Season two captures that idea—of the massive, inhuman networks mankind creates for commerce—in the signature visual of the season, its aerial establishing shots of California freeways, with their vast curlicued interchanges. But that image also feels symbolic. For season one’s Rust Cohle, time was a flat circle. Season two thus far looks more like a tangle, going nowhere interesting.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com