The people of Deir ez-Zor are surrounded—and scared. Fighters from the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria already control about 40% of this city in Syria’s eastern desert and have encircled the rest of the town in a siege that began in December. Residents told a Western photographer who visited the city in May that they are familiar with the track record of the extremist Islamist group surrounding them: many have seen films of ISIS beheading and crucifying people it considers opponents and criminals, and they’ve heard the stories about the theocratic tyranny ISIS imposes on the areas it controls in Syria and Iraq. The 228,000 people still living under government control have every reason to be afraid.

The photographs on these pages were taken by the Western photographer, whom TIME has agreed not to name out of concern for his safety and who worked in the government-controlled part of Deir ez-Zor for three weeks. The images provide a rare look at the fighting from inside the besieged city. (The photographer was given access to the military by the dictatorial regime of Syrian President Bashar Assad and was protected by government bodyguards. He says the government allowed him to take photographs without hindrance, but he says the local people he communicated with were unlikely to speak freely in the presence of officials.)

The people in the government-controlled section of Deir ez-Zor make up the largest single community in Syria under siege from any side in the brutal civil war, according to the U.N. The Syrian government is fighting to keep the city in part because the battle ties down ISIS forces that might otherwise push west toward Damascus. On May 21, ISIS overran Syrian government troops in the city of Palmyra, 210 km southwest of Deir ez-Zor. Four days earlier, ISIS had taken the Iraqi city of Ramadi, capital of the war-torn Anbar province. In both cases the group marshaled forces and pushed back government troops. Residents and government soldiers in Deir ez-Zor worry that the city might be the next major target for the militants in a war that began in 2011 and shows no sign of ending.

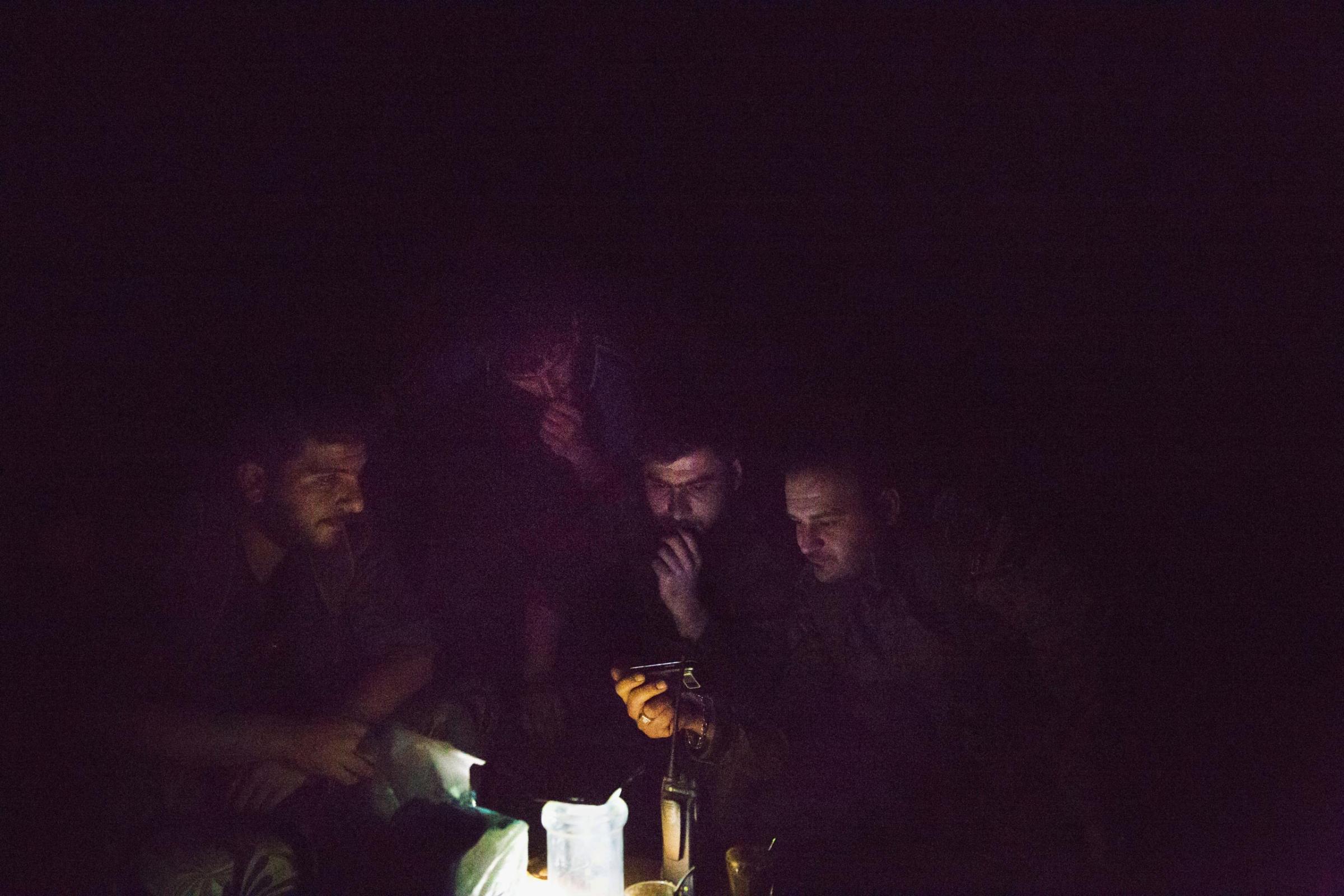

In phone interviews from Damascus and Beirut, the photographer described life in the increasingly fearful city. The Euphrates River runs through Deir ez-Zor and forms something of a divide between the two warring parties; ISIS occupies the northeast side and government forces control the southwest, he said. ISIS also controls slivers of territory on the southwest bank. He said the main focus of ISIS’s attacks is the military air base southeast of the city; the flights that land at the base have become the only way in and out of the government-controlled parts of Deir ez-Zor. ISIS has cut power supplies to the city, and it controls the nearby farmlands and oil fields.

The photographer said the ISIS-controlled parts of the city appear to be greatly damaged by artillery and aerial bombing, while the government-held areas have suffered relatively minor damage. The siege means the government-controlled section relies on the nightly arrival of a large Syrian air-force-operated cargo plane, which has a payload of more than 46 tons and transports munitions, food and medical supplies.

Assad and many of his top aides are from the Alawite sect of Shi‘ite Islam, a minority that constitutes about 12% of the Syrian population. Most of the opposition—moderate or extremist—comes from the Sunni Muslim majority. In Deir ez-Zor most residents are Sunni. The photographer didn’t see any sign of resistance against the regime forces from locals.

Normality alternates with anxiety in the city. Thousands of students attend the university, and the schools remain open. Traffic cops in black trousers, pressed white shirts and white helmets patrol the streets. But when news spreads of a new supply of cigarettes or bread, lines form rapidly. One man joked to the photographer about residents taking selfies with the lone tomato one trader had for sale.

The photographer wasn’t able to assess how many government soldiers formed the Syrian military contingent in Deir ez-Zor. Those he met seemed determined to fight on, knowing that defeat would almost certainly result in their slaughter. The local Sunni Shaitat tribesmen, who fight with the army, are witness to ISIS’s brutality. After the tribe resisted the ISIS takeover of the local oil fields in July, the militants executed at least 700 of them, according to locals and a human-rights group. Few doubt that the fate of the defenders of Deir ez-Zor would be any different if ISIS prevails.

Conal Urquhart is a Senior Editor at TIME. He is based in London.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com