This post is in partnership with History Today. The article below was originally published at HistoryToday.com.

‘[They] hit the prisoners, who were almost as thin as skeletons with a thick stick … withholding of food and beatings, [they] also made the prisoners stand for hours’

Scenes like this were inflicted by thousands of SS guards who reigned terror upon millions of prisoners interned in the hundreds of concentration camps throughout the Nazi regime. Names such as Josef Kramer, Rudolf Hoess and Theodor Eicke have become synonymous with such atrocities. Yet, to the female prisoners held in camps such as Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen and Ravensbrück, the names Irma Grese, Maria Mandl and Dorothea Binz – amongst many others – instilled as much, if not more, panic and fear than those of the SS men. In fact, the scene described above was committed by the Aufseherin (female overseer) Lehmann at Ravensbrück concentration camp, and was far from unusual in the female sections of camps.

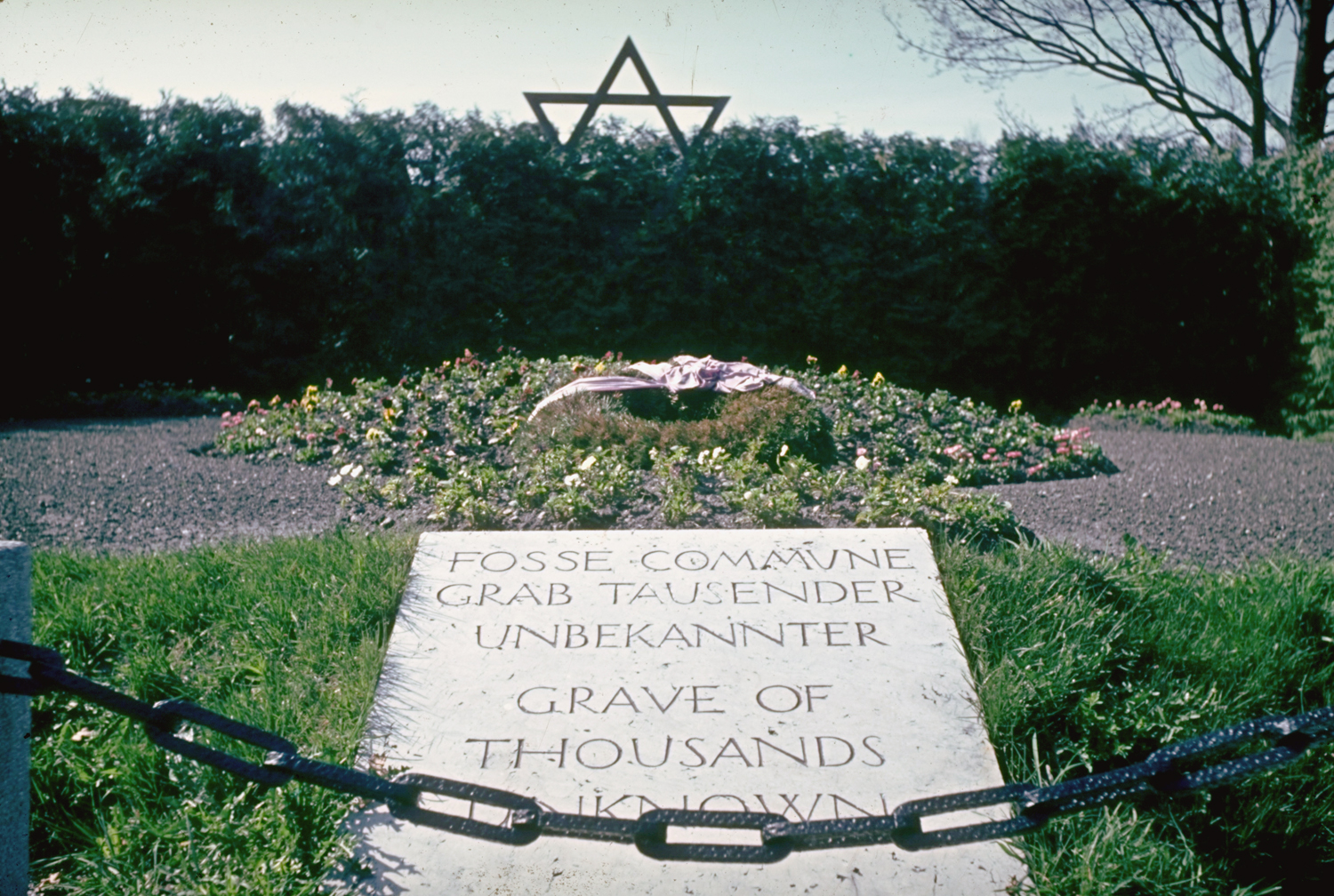

Of the 37,000 SS guards who actively participated in the daily suffering, torture and death of the internees, approximately 10 per cent were female overseers. Some of these overseers, including Irma Grese, were sentenced to death along with their male colleagues for ‘murder’ and ‘crimes and atrocities against the laws of humanity’. Others were sentenced to between one year to life imprisonment. Few were acquitted. Their role in the Third Reich was a far cry from the Kinder, Küche, Kirche (children, kitchen, church) propaganda embedded in Nazi philosophy; they too were cogs in the killing machine of the Holocaust that led to the death of at least 1.5 million Jews.

Irma Grese, known as the ‘beautiful beast’ of Belsen, was, according to the charges brought against her at the Belsen Trial in 1945, one of the ‘most sinister and hated figures’ of the camps. Witnesses claimed that she used to beat women until they collapsed.

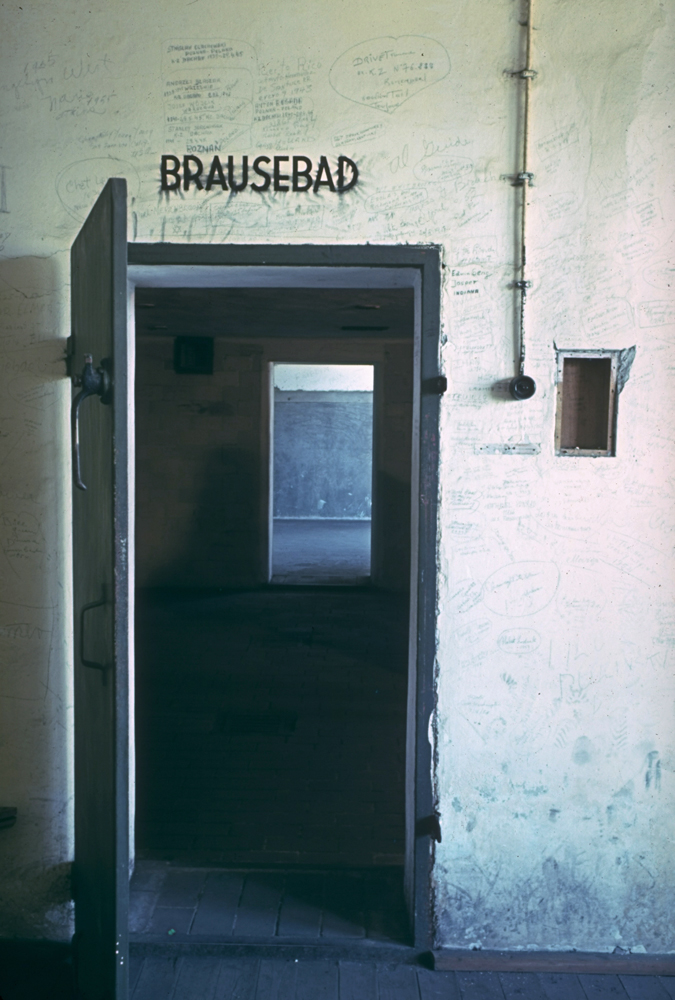

And she was not the only one. Renee Lacroux, a French prisoner held in Ravensbrück, told of how several female guards ‘killed the weaker ones and threw many of the girls onto the ground and trampled on them’. Just like their male counterparts, the female guards upon entering the camps were trained to become hardened and to punish prisoners severely when necessary. Many became accustomed to beating and kicking prisoners – sometimes to the point of death – with their jackboots, sticks, truncheons and, in the case of Irma Grese, with a whip made of cellophane. Some were involved in administering lethal sterilization experiments and many were present in the selection of those prisoners to be sent to the gas chambers. Some also carried a gun.

Not all guards, however, became equally accustomed to brutality. There were reports by some former prisoners of ‘humane’ guards: one such guard called Krüger is alleged to have shared extra food with her workers in Ravensbrück. And this case cannot have been isolated; an order was sent by the SS Obergruppenführer (senior group leader) to remind female overseers that they were not to have personal dealings with inmates. There was no equivalent order sent to SS men. Equally, murder was not customary for the female guards. They rarely used their guns and none, without exception, administered the fatal Zyklon B gas that killed over 6 million Jews, gypsies and asocials – amongst others – in the gas chambers. Direct killing was viewed solely as a masculine endeavor. This is not to say, however, that female guards did not kill the prisoners indirectly through their ill-treatment and violence – and violence was the norm throughout the camp environment.

So, how did these guards, described as ‘sadists’ and ‘beasts’ by former prisoners, find themselves committing these crimes against humanity? Elisabeth Volkenrath, chief female overseer in Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, sentenced to death in 1945, was an unskilled laborer prior to becoming a guard. Ruth Closius, also sentenced to death for her exceptional cruelty, had dreamed of becoming a nurse but, since she left school too early, became a saleswoman in a textiles warehouse. The notorious Irma Grese worked at a dairy farm after leaving home at 15 years of age. Before entering the camps these women were, to all intents and purposes, ordinary women leading ordinary lives.

Many were not even members of the Nazi party. Unlike the overwhelming majority of male SS guards who were ardent believers in Nazi ideological and racial beliefs, less than 5 per cent of female guards were formal members of the Nazi party. For some then, the lure of a stable, well-paid job complete with uniform and accommodation was enough. Female guards earned approximately 185 RM, considerably more than the average wage of women of the same age in an unskilled factory job, 76 RM. Becoming a guard represented upward mobility for many of these under-educated and lower-class women. Even so, the recruitment campaign from 1942 onwards failed to attract the large numbers the SS needed in order to manage the increasing number of female prisoners. Instead, they had to turn to conscription. Even Irma Grese claimed that the labor exchange ‘sent [her] to Ravensbrück’, where all female guards underwent training, and that ‘[she] had no option’.

Whatever the reasons for becoming guards – financial, a thirst for adventure or conscription – Nazi ideology was rife and the ill-treatment of ‘enemies of the state’ was commonplace. As predominantly young, Aryan women aged between 17-45 (as strict entry criteria), these women had grown up in the midst of Nazism; many had been members of the Bund Deutscher Mädel (League of German Girls) and had grown up with Nazi propaganda. Further ideological training, which included propaganda films such as Jüd Süss, was imposed upon new recruits during their orientation period at Ravensbrück and manifested itself as violence within a matter of days. One prisoner noted how it took one guard just four days.

Many of these women were never brought to trial and were able to return to their pre-war, ordinary lives. For those who were brought to trial, however, such as Irma Grese, their ordinary life became a distant prospect to which they were never again able to return. Seventy years after the liberation of the camps, it is important to remember that women were not only victims, mothers or wives; they too were active agents in sustaining the terrors experienced by millions during the Holocaust.

Lauren Willmott works at the National Archives, London.

Ghosts in the Sun: Hitler's Personal Photographer at Dachau, 1950

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com