It would seem to go without saying that breaking out of jail is a criminal act. As the manhunt in New York state continues, the two convicted killers whose escape from Clinton Correctional Facility was discovered on Saturday have joined a long list of truly dastardly break-outs–some of which retain a certain magician-like mystique. The 20th century’s most prolific prison-breakers include some of its most infamous criminals, from John Dillinger to James Earl Ray, the latter of whom earned himself the nickname “the mole” for his many attempts to break out.

But the history of jail breaks also reveals an odd counterexample. Not every single instance has actually been criminal.

Case in point: the 1971 escape of Joel Kaplan from a Mexican prison. Here’s how TIME described the bravado breakout that August:

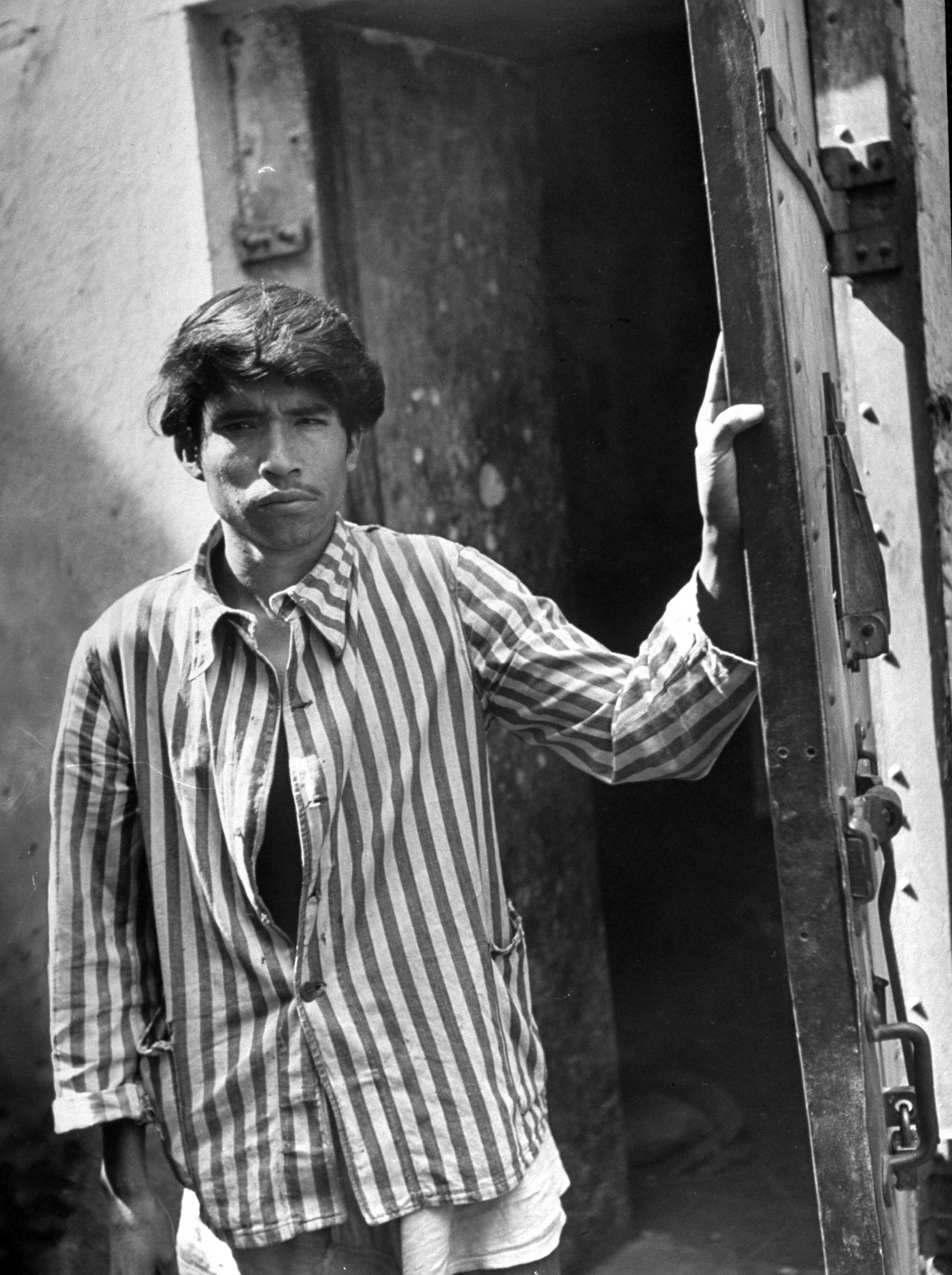

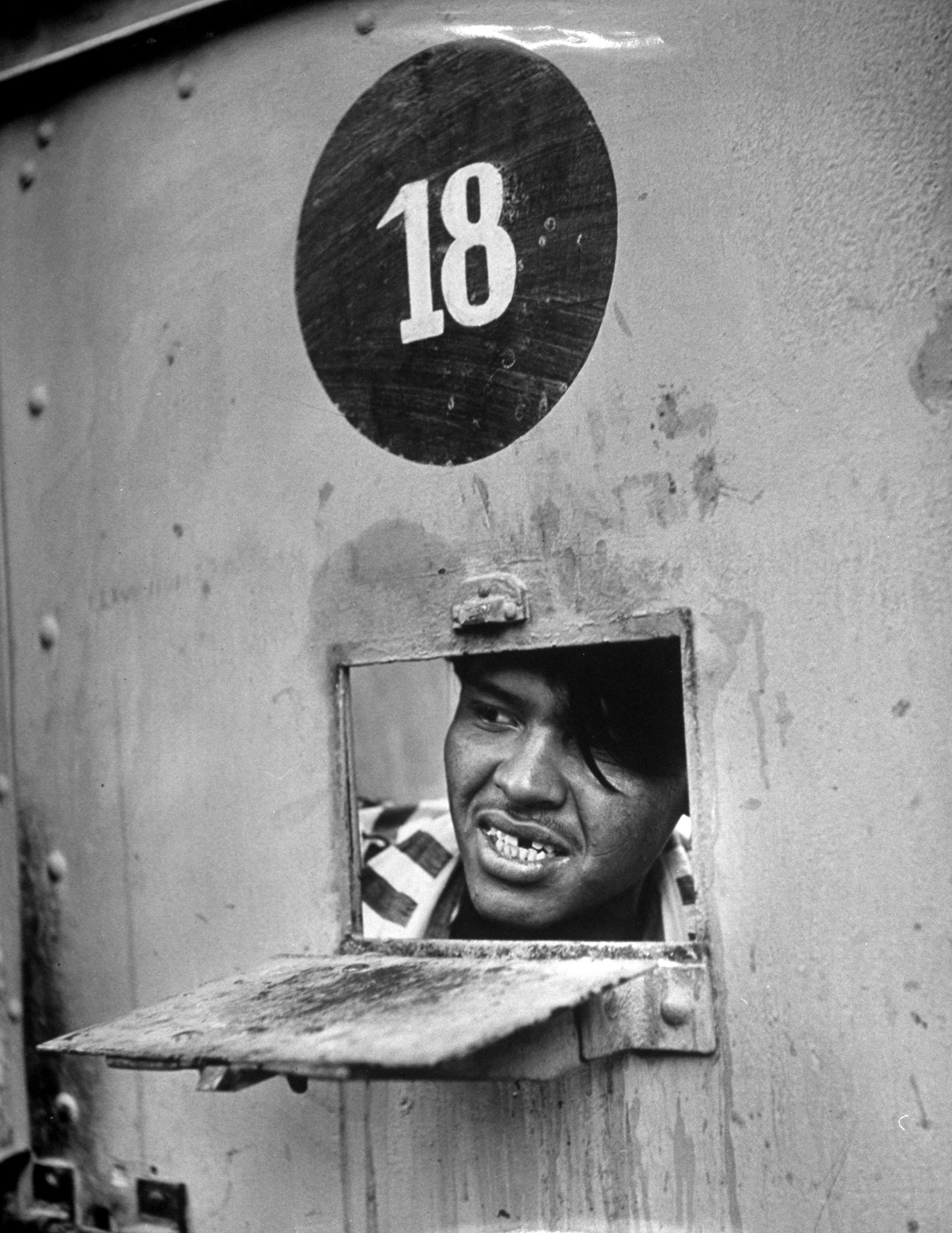

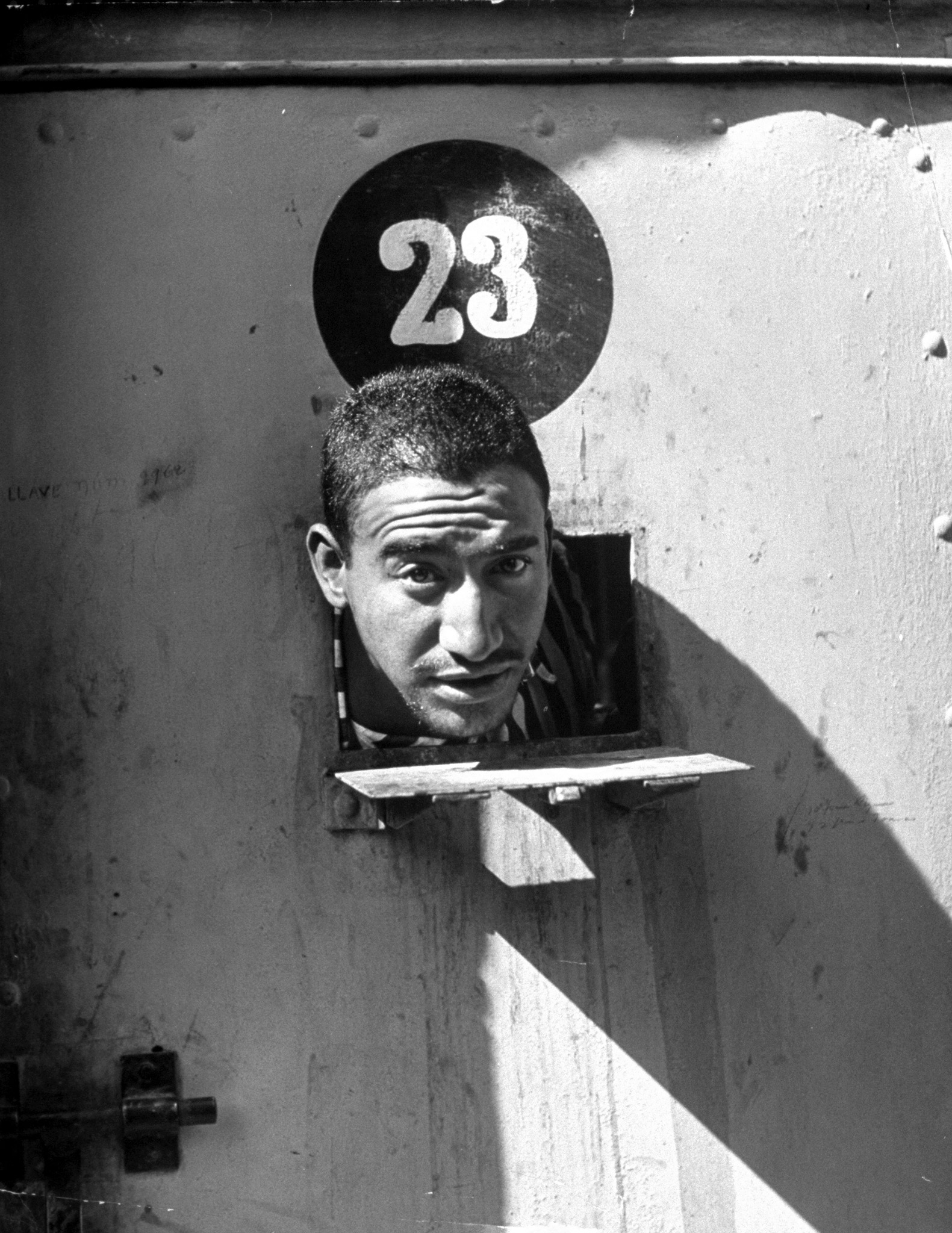

Most of the 136 guards at Mexico City’s Santa Maria Acatitla prison were watching a movie with the prisoners last week when a Bell helicopter, similar in color to the Mexican attorney general’s, suddenly clattered into the prison yard. Some of the guards on duty presented arms, supposing that the helicopter had brought an unexpected official visitor. What they got was a different sort of surprise. As the chopper set down on the paving stones, two prisoners dashed out of Cell No. 10. The men were airborne in less than two minutes. One of the most enterprising jailbreaks in modern times had been accomplished without a shot being fired.

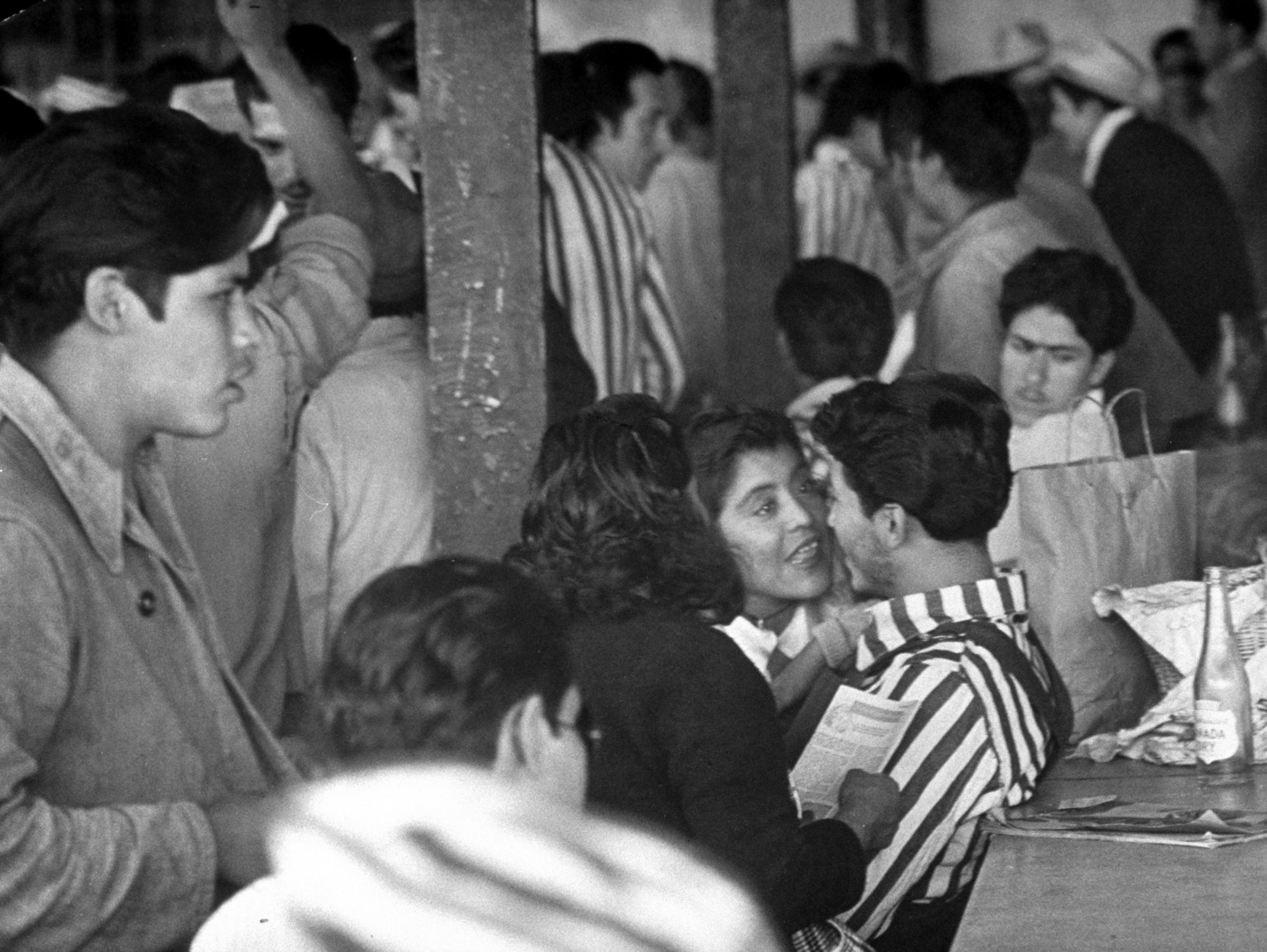

Kaplan, one of the two escapees, was a prominent New York businessman from a wealthy family. In 1962, Kaplan’s business partner Louis Vidal Jr. had been proclaimed dead in Mexico City; Kaplan had been charged with killing Vidal, even though there seemed to be doubts over whether the body in question was actually Vidal’s. (The other escapee was a Venezuelan named Carlos Antonio Contreras Castro, in jail for counterfeiting; his story was much less widely covered in the American press at the time.) After the escape, the prison noted that the Kaplan’s and Castro’s wives had visited the day before, accompanied by an American man who seemed to be surveying the prison yard.

Following the flight to freedom, the helicopter delivered the two men to a private plane at a nearby airport, which in turn delivered them to an airport near the Texas border, where they split up. Castro went to Guatemala; Kaplan made his way to California.

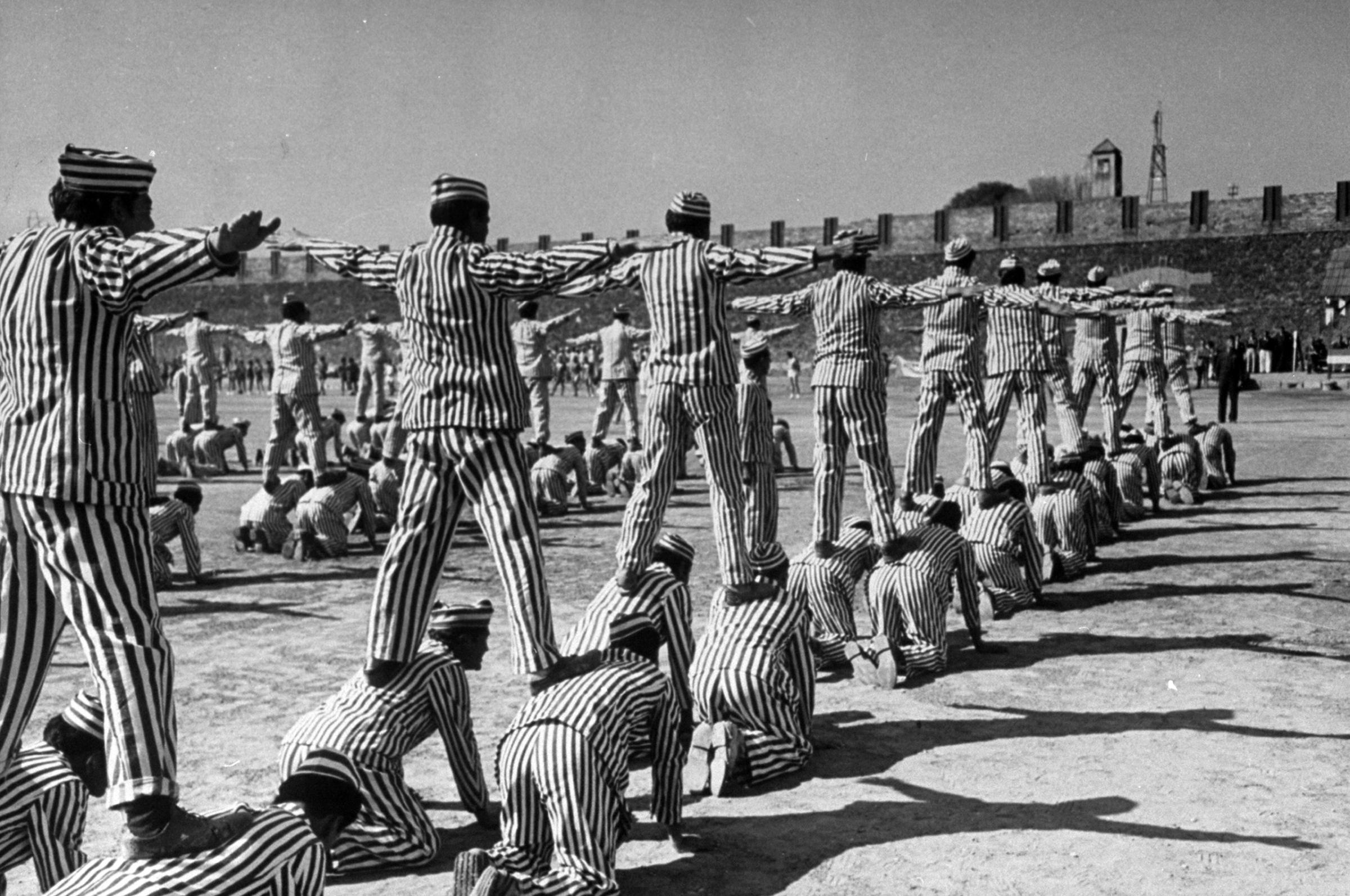

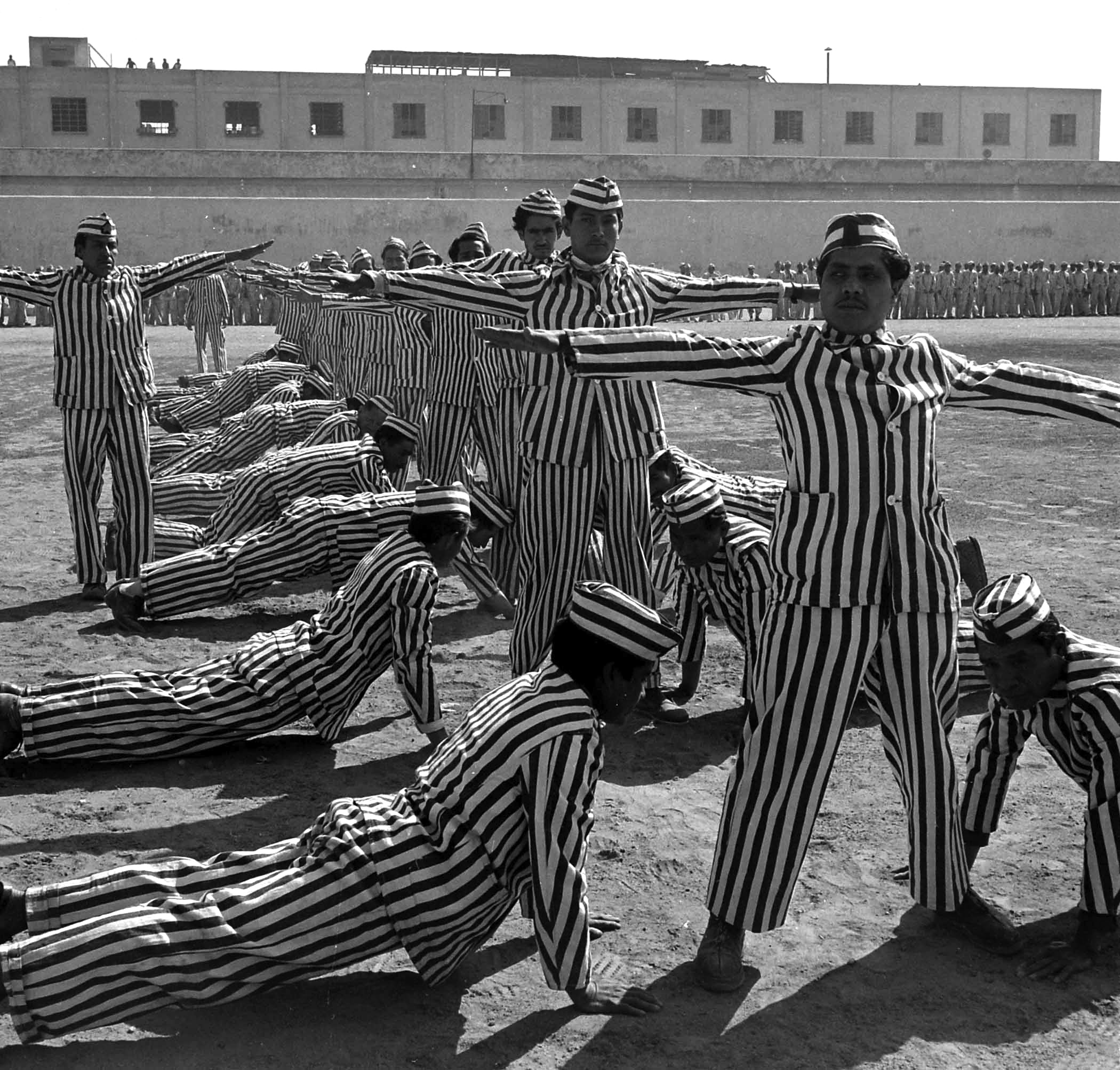

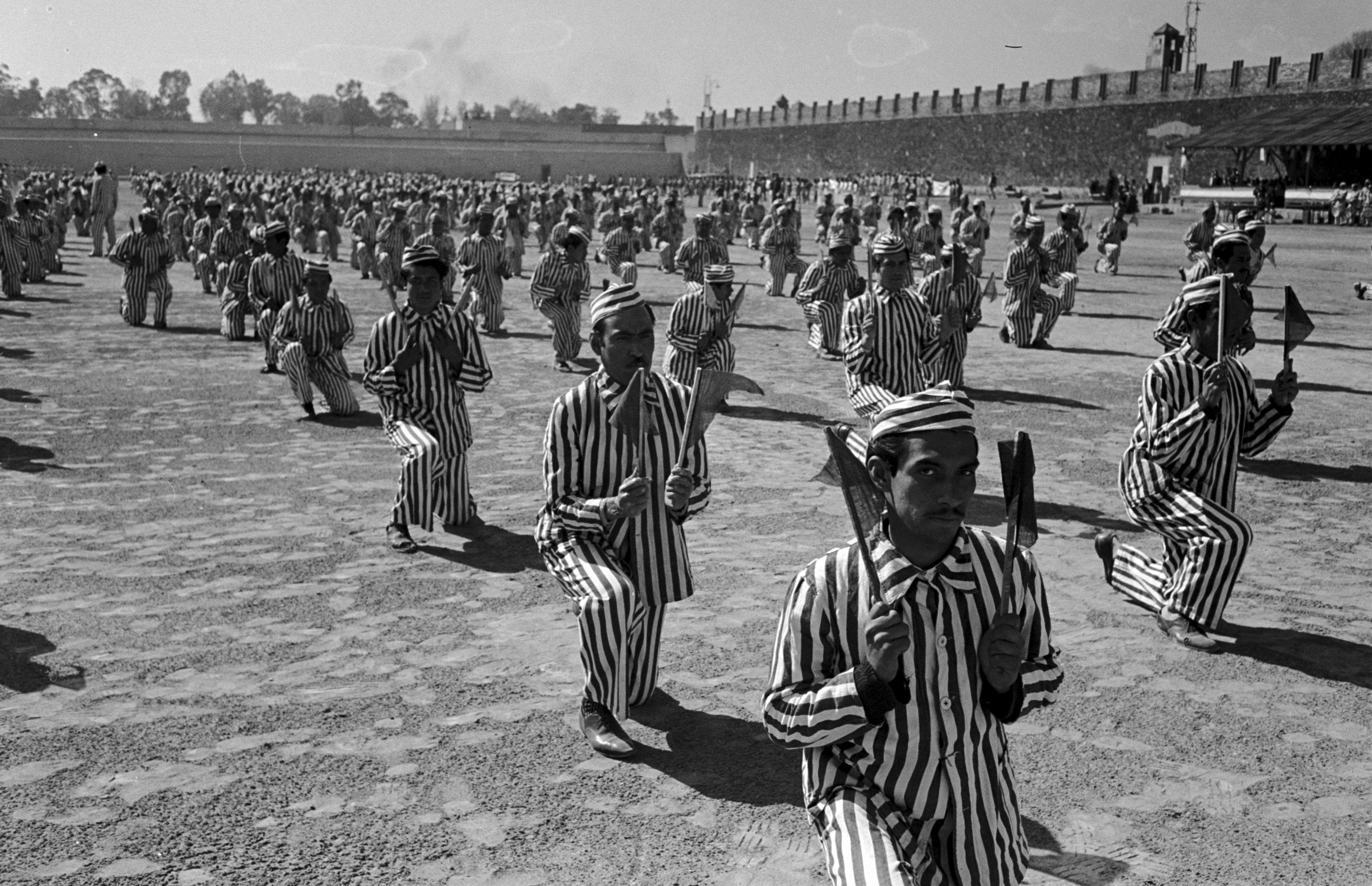

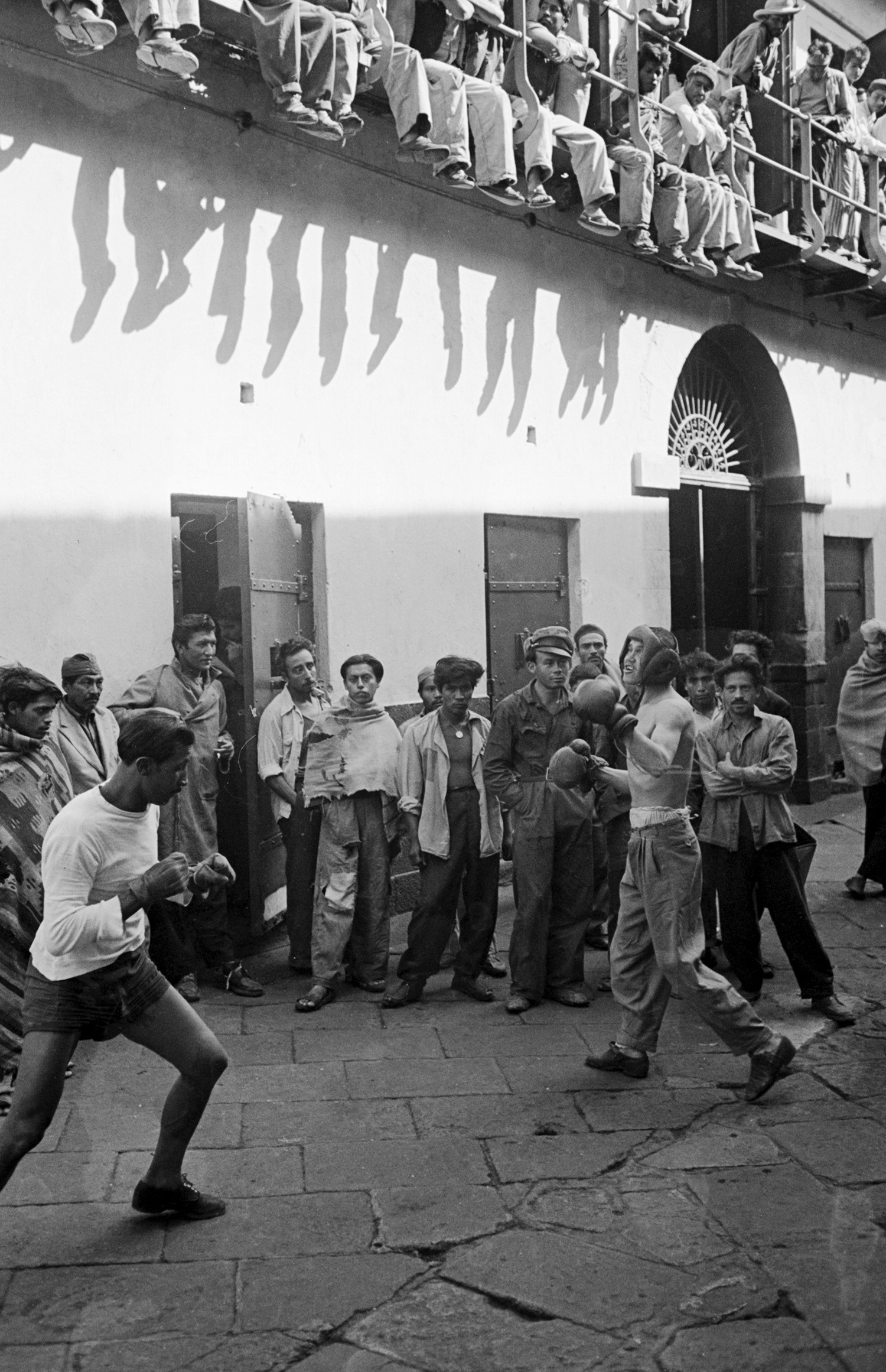

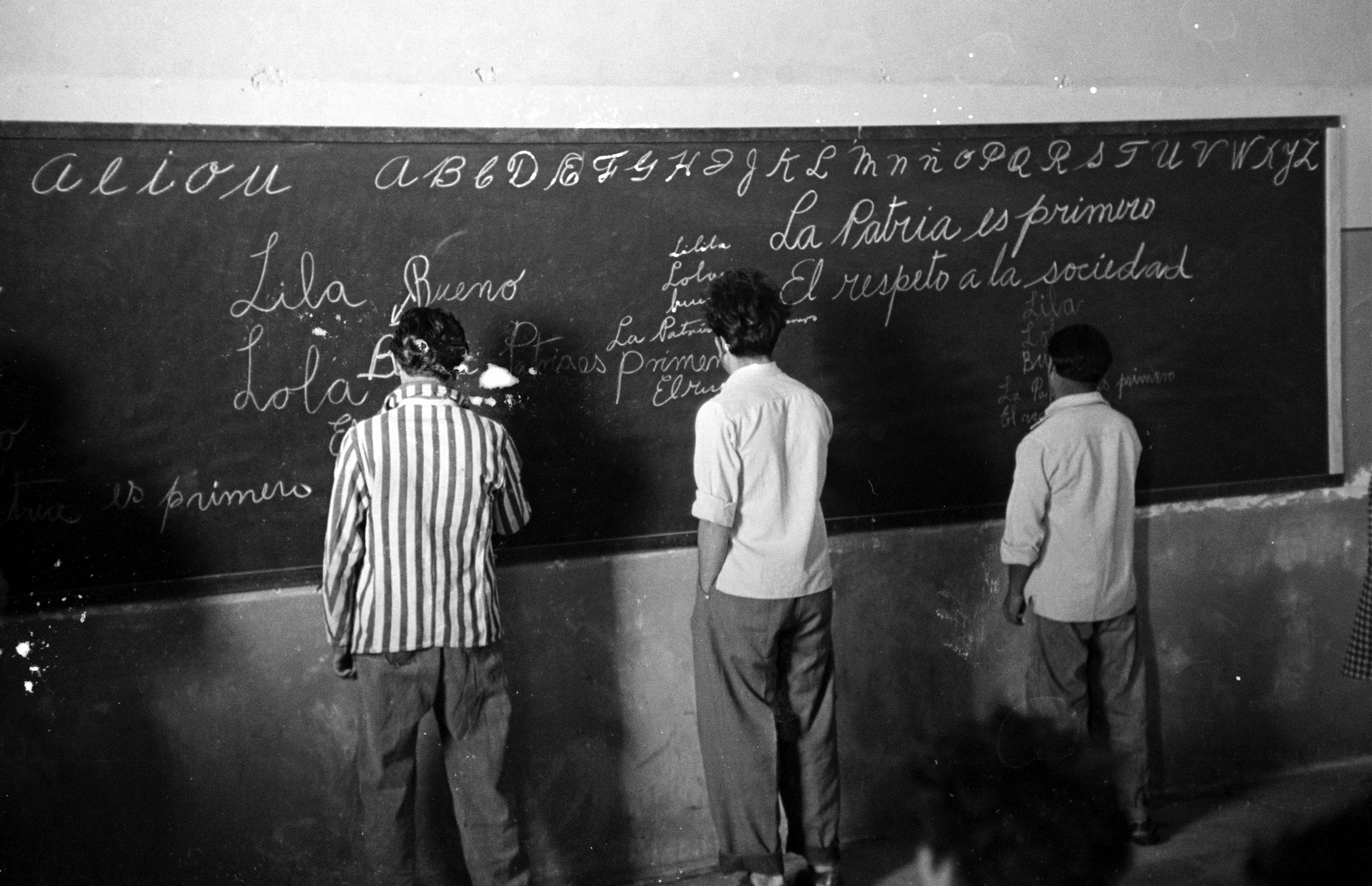

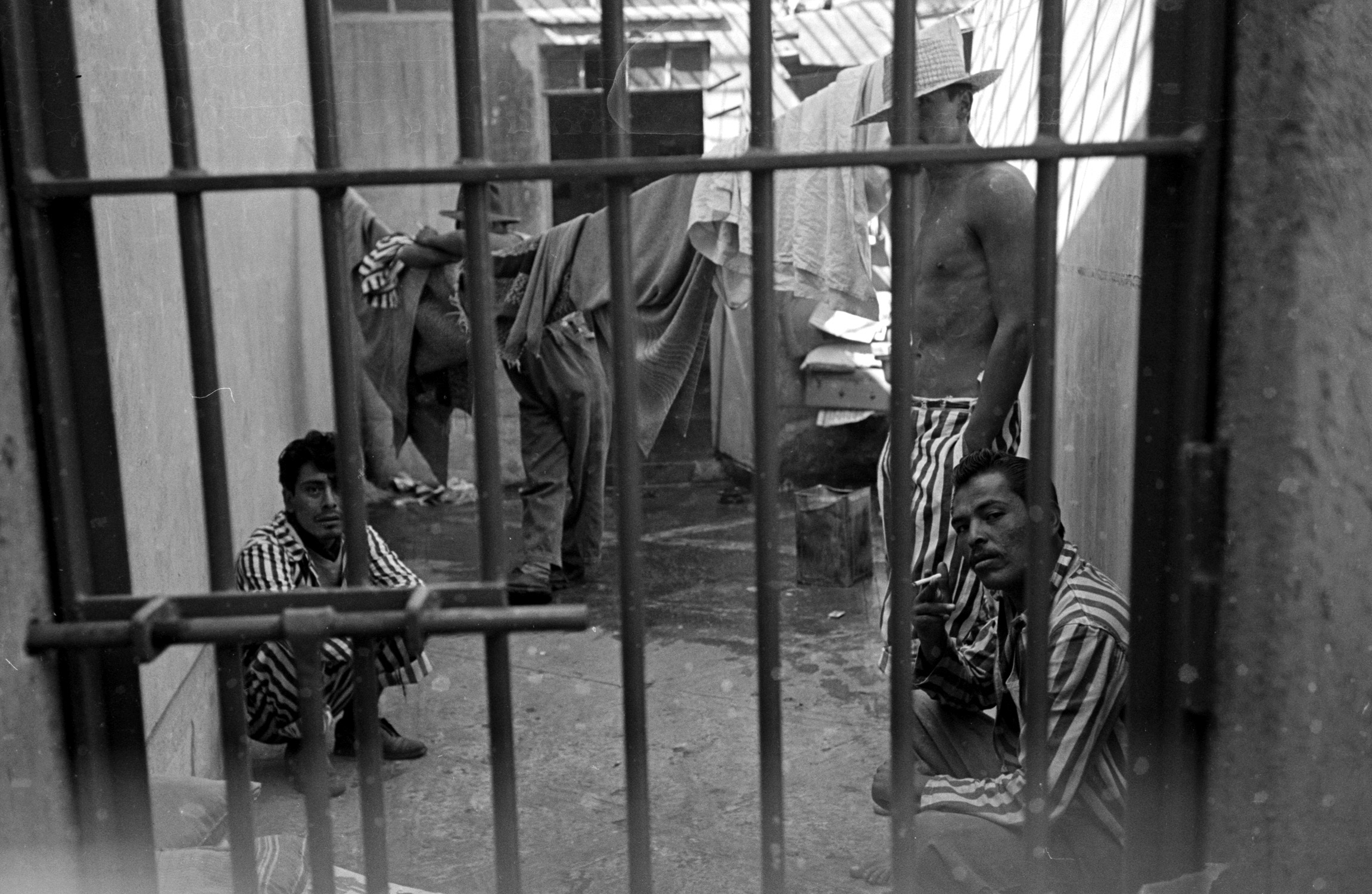

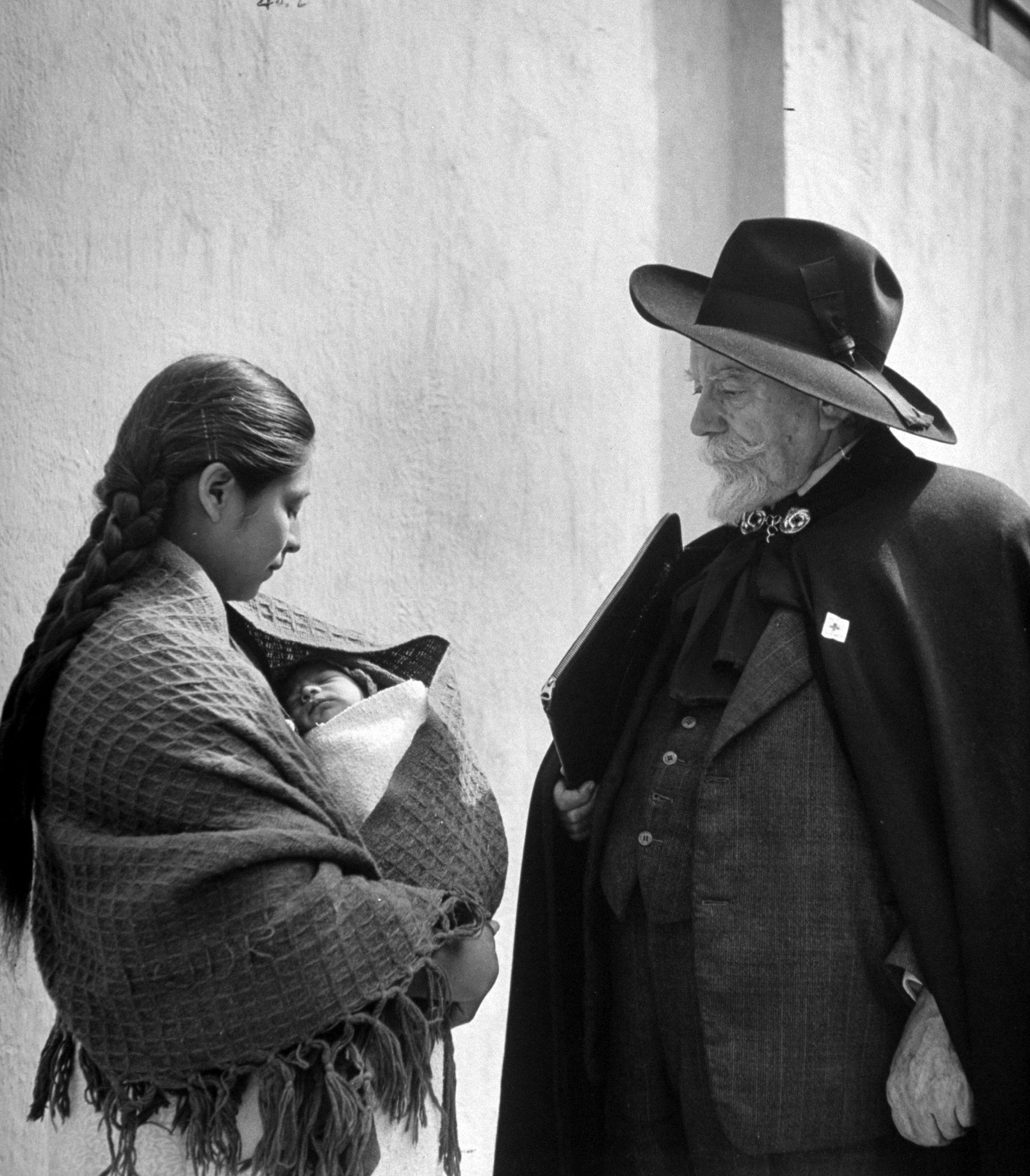

Life Inside Mexico's 'Infamous Cesspool,' the Black Palace Prison

The real twist, however, came later. After arriving in the U.S., Kaplan insisted that the entire process had been entirely legal. The prison in Mexico had not been damaged in any way. No one had been hurt. Both the helicopter and the private plane used within Mexico were purchased outright rather than rented, so it would be impossible to make any claim that they had been used improperly, and everything about the flight was done according to FAA standards. When crossing into the U.S. in Texas, Kaplan and the pilot both used their correct names when speaking with customs officials. “His escape, the lawyer claims, was perfectly legal since jail breaks are a crime in Mexico only if violence is used against prison personnel or property or if prison inmates or officials aid the escape,” TIME reported. “Mexican authorities disagree, insisting that the use of accomplices—the pilots, in Kaplan’s case—makes the escape illegal. However, Mexican officials have not yet initiated extradition proceedings against Kaplan or his partners, who seemed to have pulled off a practically noncriminal crime.”

The jailbreak was the inspiration for the 1975 Charles Bronson/Robert Duvall movie Breakout, and that coda proved to be in some ways more shocking than the real thing, as TIME reported: “[T]hough the actual 1971 jailbreak went uneventfully, not so the movie version. Appearing unexpectedly on the set, Kaplan and [pilot Victor] Stadter watched in amazement as two Jeeploads of movieland police blasted away at Actors Bronson and Duvall re-enacting the escape. Said Stadter afterward: ‘I was more scared watching all this than when we did the caper.'”

As for the real-life Kaplan, though he was not actively pursued by authorities on either side of the border—and though the CIA and he both denied that he was involved with their espionage operations—he was apparently living incognito. And he was as good at that as he was at breaking out of jail: he been heard from publicly since.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com