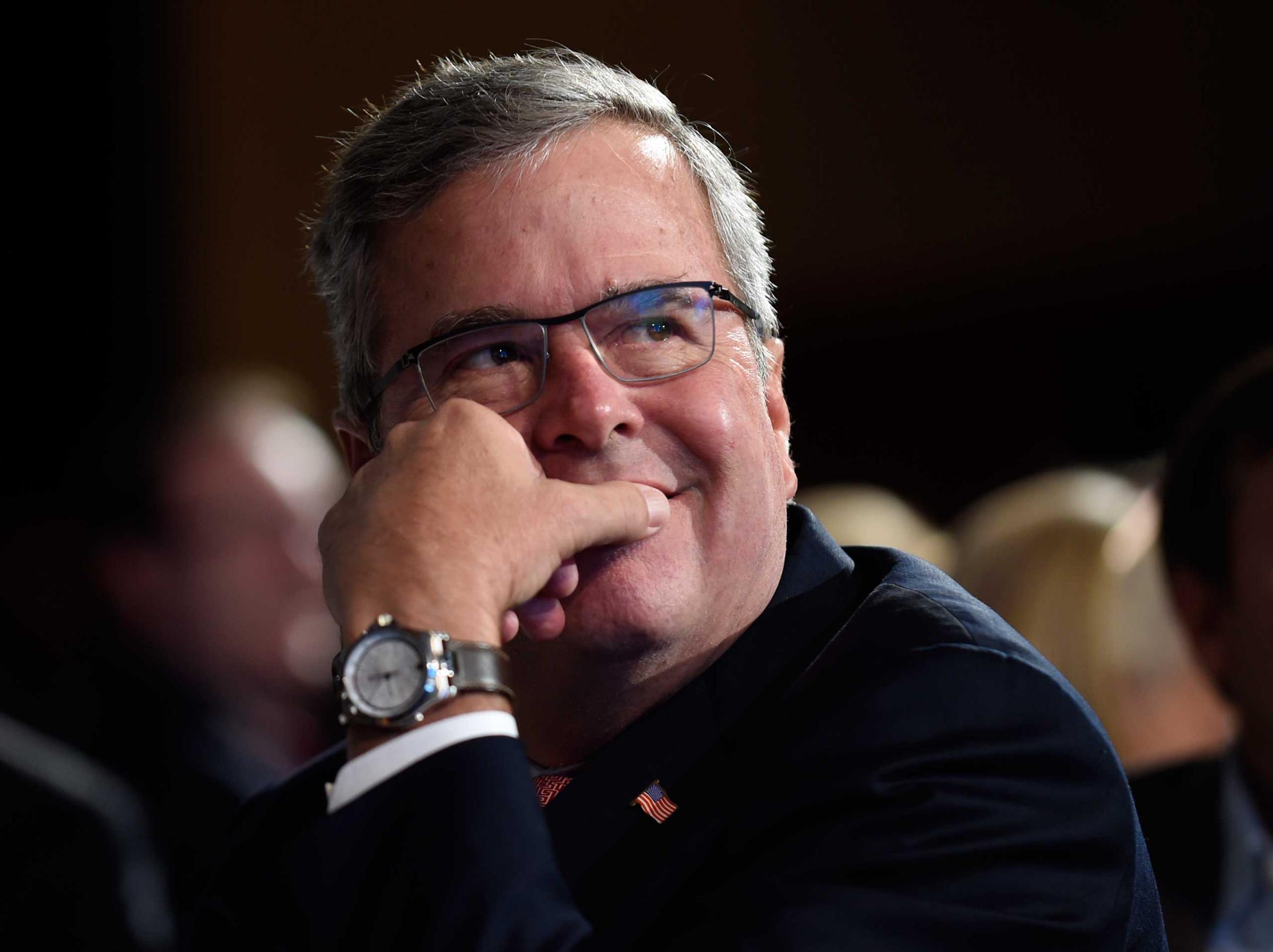

Jeb Bush was in Maine for his mother’s birthday. But 1,400 miles away, amid Iowa cornfields, the former Florida Governor loomed large over the other Republicans also seeking the GOP’s presidential nomination. The son of one President and brother to another was nowhere to be seen as seven of his likely rivals roamed a grassy field, shaking hands and taking pictures with Iowa activists.

Under the overcast skies, each was trying to win the next-up fight playing out inside the Republican Party: the contest to be the most credible alternative to Jeb Bush.

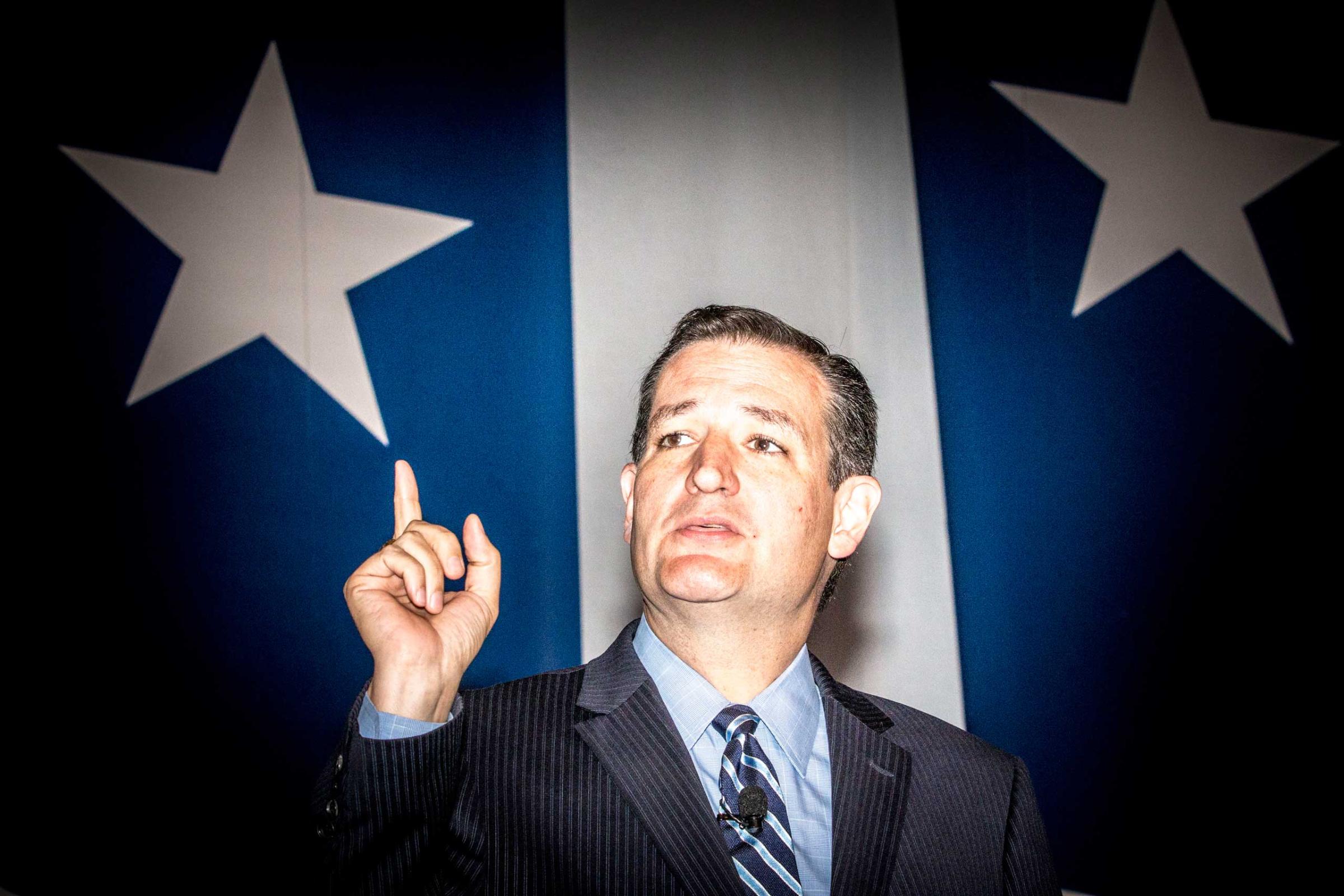

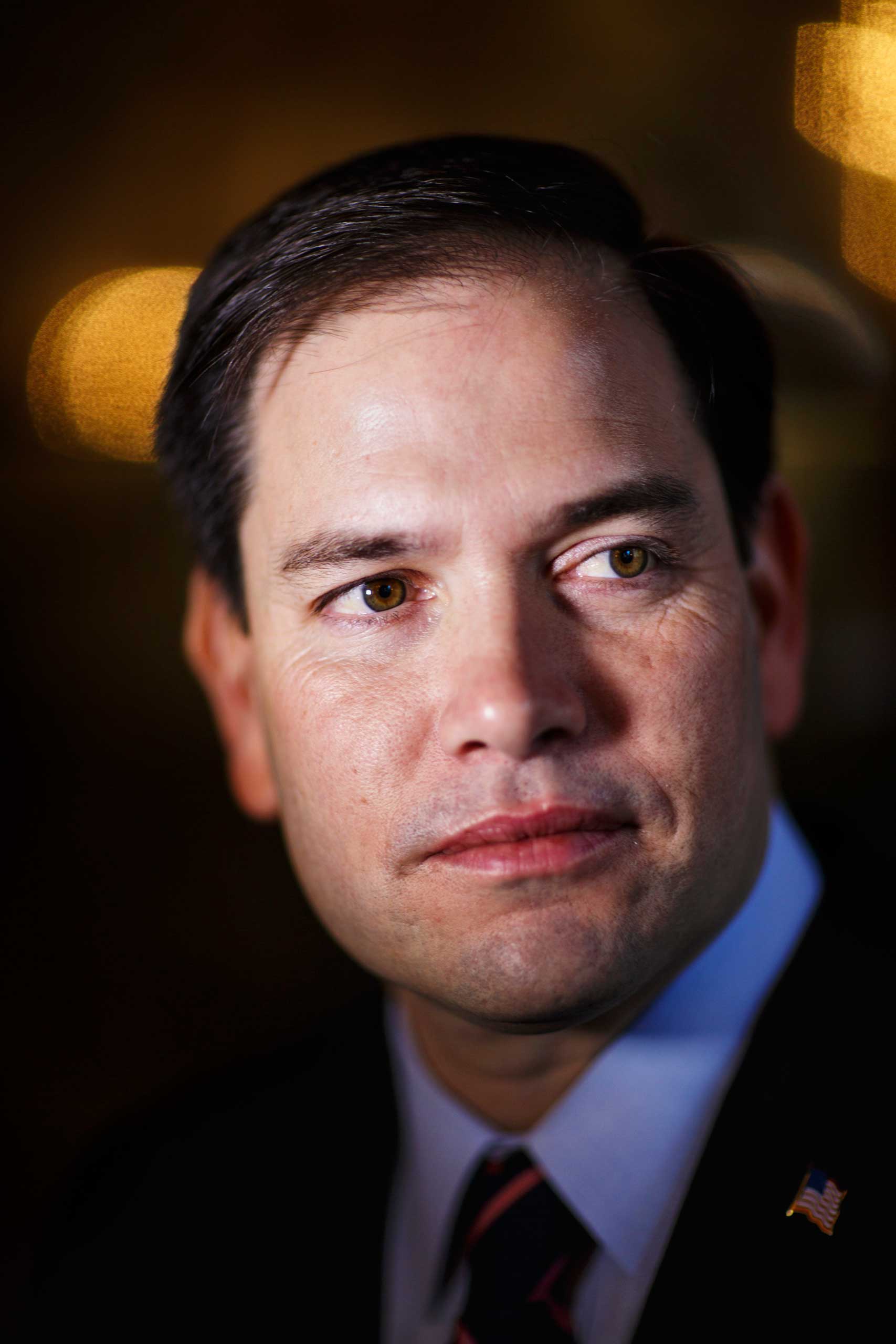

Iowa is the traditional proving ground for the candidates looking to represent that small but vocal ultra-conservative bloc inside the GOP’s often fractured coalition. But this year, two of the leading rivals in that corner of the party also have the support of establishment-minded Republicans, who are more inclined to support Bush. Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker and Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida each have the potential to win over both the fire-breathing social conservatives as well as the mild-mannered, business-oriented moderates. That gives them a crossover appeal that could topple Bush, or at least trip up his march toward the nomination.

But there’s only room for one challenger.

The battle between Walker and Rubio had its unofficial kickoff on Saturday, as the pair looked to find an upper-hand among the churchgoing crowd in Iowa. They did not directly engage each other, but each was trying to find an advantage.

Walker spent half of his turn speaking to Iowa activists focused on growing up the son of a pastor in tiny Plainfield, Iowa. “I look back at my life, and I realize my brother and I did not inherit fame or fortune from our family,” Walker said, making an implicit Bush critique as he emphasized the values he learned from his parents in small town Iowa. “What we got was more important, and that was the belief that if you work hard and play by the rules, you can do and be anything you want in America.”

A few hours earlier, Rubio was pitching the needs for his party to adapt to a new century, why the ideas of yesterday are no longer adequate and, perhaps most importantly, why he is the best vessel to take them to that future. Tucked within his standard campaign speech that promises a New American Century, he made sure the audience knows he and his wife were sending their four children to a school where they learn Scripture between lessons on reading and arithmetic. “We send my four children, I’m proud of this, to receive a private, Christian-based education,” Rubio said during a packed campaign rally in Ames.

Behind the scenes they are locked in a struggle for many of the same potential donors, endorsers, and campaign operatives. There is a wide swath inside the GOP uneasy with the prospect of nominating a Bush to face off against former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the likely Democratic nominee, while his positions on immigration and education upset others. Rubio and Walker are positioning to be the alternative to that dynastic struggle, making a generational play against the older Clinton, and an ideological one against Bush.

At roughly the same age—Walker is 47; Rubio, 44—they each represent a new face for the Republican Party. “The Republican Party is going to die if they keep putting up old, rich guys,” said Mary Martin, a 22-year-old Iowa State University student who stopped by a Rubio event this weekend. “He’s not from a trust fund,” she said of Rubio, an Iowa-polite jab at Bush. But like many, Martin is still shopping and wants to see Walker soon.

See the 2016 Candidates Looking Very Presidential

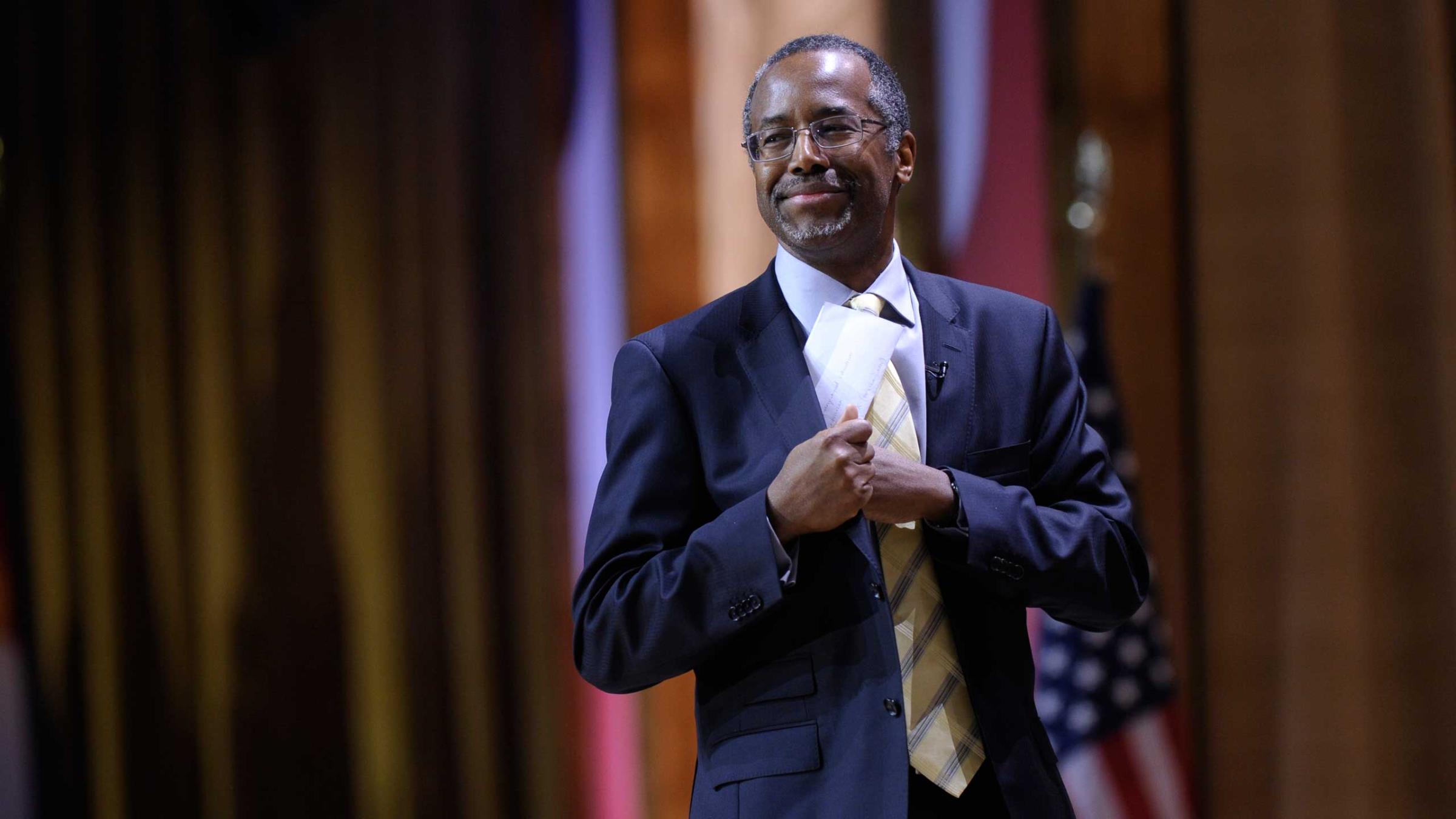

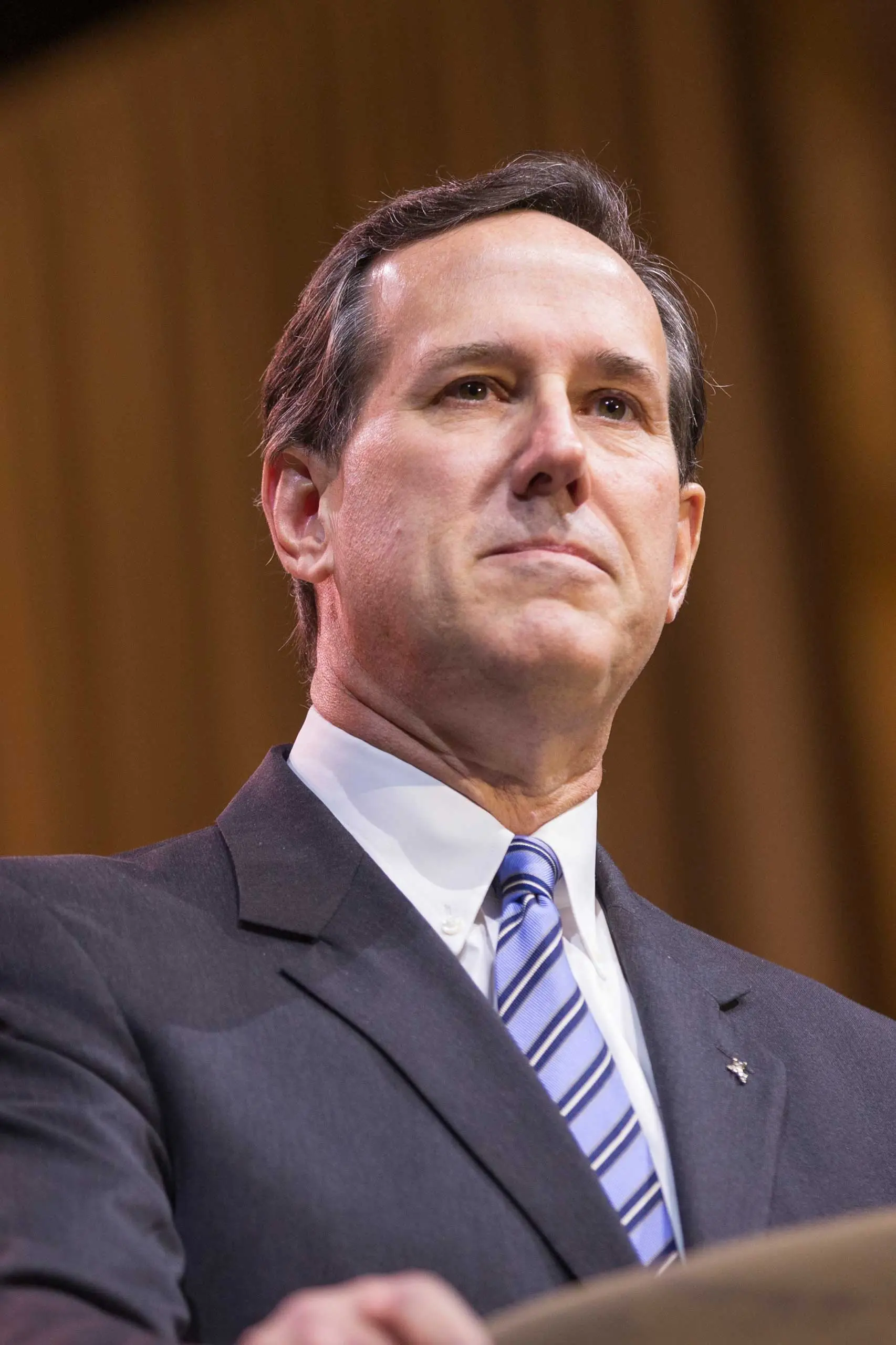

Evangelicals and social conservatives have always had tremendous sway inside the Iowa Republicans’ tent. It allowed former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee to win 2008’s caucuses, and former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum to triumph, albeit by a hair, in 2012. But the 2016 raft of candidates features several contenders who are already keeping the pews at an arm’s length with an eye toward capturing more secular-minded voters. Sen. Rand Paul, a libertarian darling, has steadfastly refused to share his views on the divisive but decisive issue of whether abortion should be available to women in cases of rape, incest or life-threatening pregnancies. Bush, whose Catholicism is a central part of his life, has shown little interest in making his faith a reason for his all-but-certain candidacy, beyond a commencement address at Liberty University last month. Conceding that segment of voters only helps contenders such as Walker and Rubio to rally them.

The leadoff caucuses are still eight months away, and even the candidates’ advisers acknowledge the polling at this point could be upended by almost anything. Walker enjoys an advantage in those polls, but even his most ardent backers are still open to someone else. Rubio is close behind in the same polls and is generally well-regarded among Republicans.

Walker has set up one of the most aggressive campaigns on the ground. He has not physically been in Iowa as much as others, such as former Texas Gov. Rick Perry, but Walker has the added benefit of being a neighbor. “Wisconsin is right next door and we hear about what he’s doing in Madison a lot,” said Donald Doudna, a 66-year-old economic development executive from Johnston. In addition, Walker spent his early childhood in Iowa—a key part of his pitch to Iowa voters.

As a mark of his status, Walker rode at the front of a mile-long procession of motorcycles with Iowa Sen. Joni Ernst to Saturday’s Roast and Ride, a combination biker rally and barbecue. After roaring into the event site, he dove into the audience to shake hands and meet with activists. As a sign of his standing atop Iowa polls, the T-shirt-clad Walker was followed by a throng of well-wishers and reporters.

Rubio spent less time mingling with the crowd and stuck to the traditional campaign uniform of slacks and a dress shirt. It was consistent with Rubio’s far more cautious route in Iowa and nationally. His strategy is slow, steady campaigning in case Walker implodes or Bush squanders his sizeable advantage.

Bush remains a political powerhouse. He took advantage of the new and untested world of outside political groups to assemble a campaign-in-waiting. He has been raising money for the super PAC that is expected to pick up the tab for his television advertising. And the Bush name still carries weight among Republicans’ establishment. “I think Gov. Bush is still probably out there up front, because he’s going to have more money than just about all of us combined,” Walker told ABC’s Jon Karl in an interview that aired Sunday, reversing his declaration in March that he was in the lead.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Write to Philip Elliott / Ames, Iowa at philip.elliott@time.com