For 40 years, a little-known conflict has opposed a group of separatists, called the Polisario Front, to the government of Morocco in Western Sahara. Generations of refugees have been forced out of the region, and yet, the world has taken little notice. For photographer Simon Brann Thorpe, this had to change. But he didn’t want to take usual photographs of conflicts. Instead, he collaborated with one of the Polisario Front’s military commanders to create a body of work that goes beyond documentary. He transformed real life soldiers into toy soldiers to examine the true impact of the war’s stalemate. He speaks to TIME LightBox.

Olivier Laurent: Why did you want to do something about the conflict in Western Sahara?

Simon Brann Thorpe: In 2004, I did a project about landmine victims there. It was my first project to try to bring awareness to the issue of landmines, which are as invisible in the area as the conflict itself–both physically and metaphorically. That was what introduced me to the bizarre, absurd nature of the conflict and how and why it’s remained invisible for so long. Fairly soon after that, I knew I wanted to go back. But I didn’t want to cover the conflict with traditional reportage, as that’s not my background or genre. The overriding question was why has this conflict in Western Sahara remained so utterly invisible for 40 years? I then attempted to imagine the emotional and physical manifestations of being trapped, powerless, in a perpetually unresolved cycle of postcolonial conflict. The concept of Toy Soldiers came to me out of this cycle of thought and it just seemed to fit perfectly with the situation on the ground as well as allowing for people in the West to have an emotional, physical and nostalgic response to a completely foreign reality, triggered by a familiar symbol of their own childhood and culture.

Olivier Laurent: Doesn’t this particular approach, where soldiers become toy soldiers, create an uniformity and a loss of identity of the individual soldiers?

Simon Brann Thorpe: War creates loss of identity (not just of the individual but also, in this case, of nation) and therefore it was one of the key narratives I wanted to communicate through the project’s concept: a reality reconstructed, placed onto a conflict that is almost utterly invisible.

Olivier Laurent: How did you find this commander and convince him to collaborate on this project?

Simon Brann Thorpe: I met the commander through the Polisario representatives in London and through contacts in the refugee camps made during my first visit there in 2004. He’s a refugee like all the other Sahrawis divided by the conflict, and the commander of a particular region known as “Liberated Western Sahara”. I think the most important thing for him was my credibility as an artist and in what the project was trying to achieve, and then on a secondary note, that he completely related to the concept through his own experience. As custodians of this little stretch of land, their existence within this conflict without end and at the mercy of other people’s decision-making is something that resonated through the concept that is a narrative on a powerless state of being.

Olivier Laurent: How did the collaboration work? Were the soldiers happy to take part in this? What was their state of mind?

Simon Brann Thorpe: The collaboration was set a long time before the image production began and took many forms, the first of which was the location scout which took place over a year ahead of the main production. Then we had to produce the bases [for the soldiers] to stand on. I wanted to have the soldiers physically act out that stance on the base rather than to add it in post-production because that enactment was an essential part of the project and concept. So we made them out of old oil drums, which we covered in paint and in sand until they were ready to be carted around to each location. The soldiers would carry them in the heat and cut their fingers on them. It was an interesting experience and one that I’ll never forget in terms of the willing participation of the soldiers in this project. It was amazing and very humbling.

Olivier Laurent: How important was that collaboration for you?

Simon Brann Thorpe: The collaboration was everything to the project! Without it, it would not have happened or it would have had a completely different feeling, resonance and credibility.

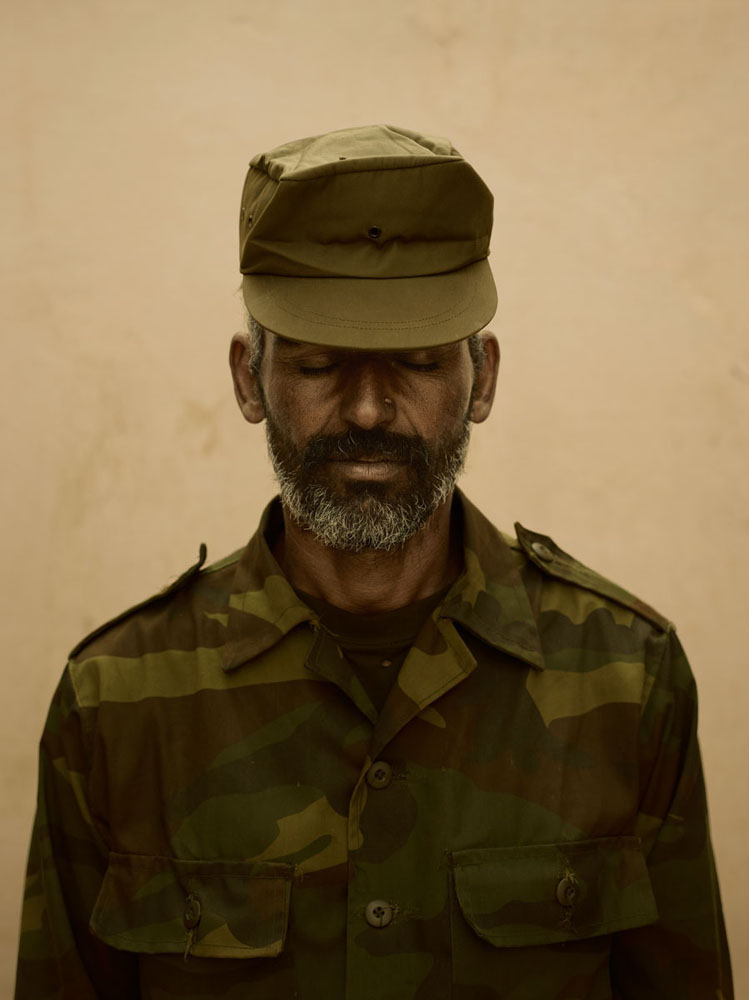

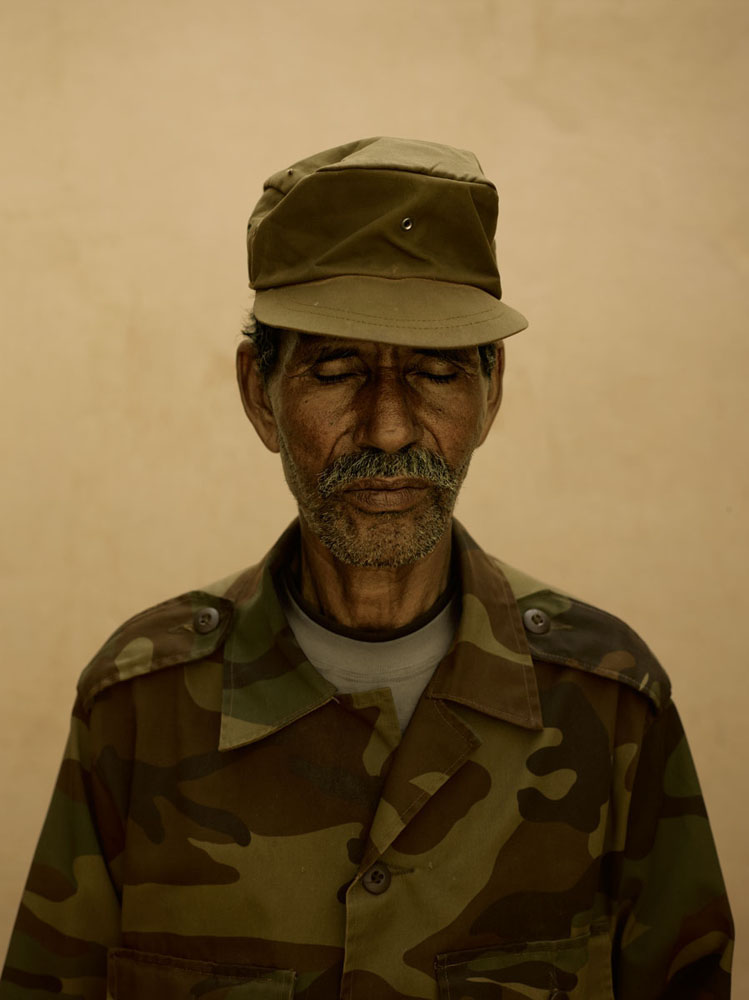

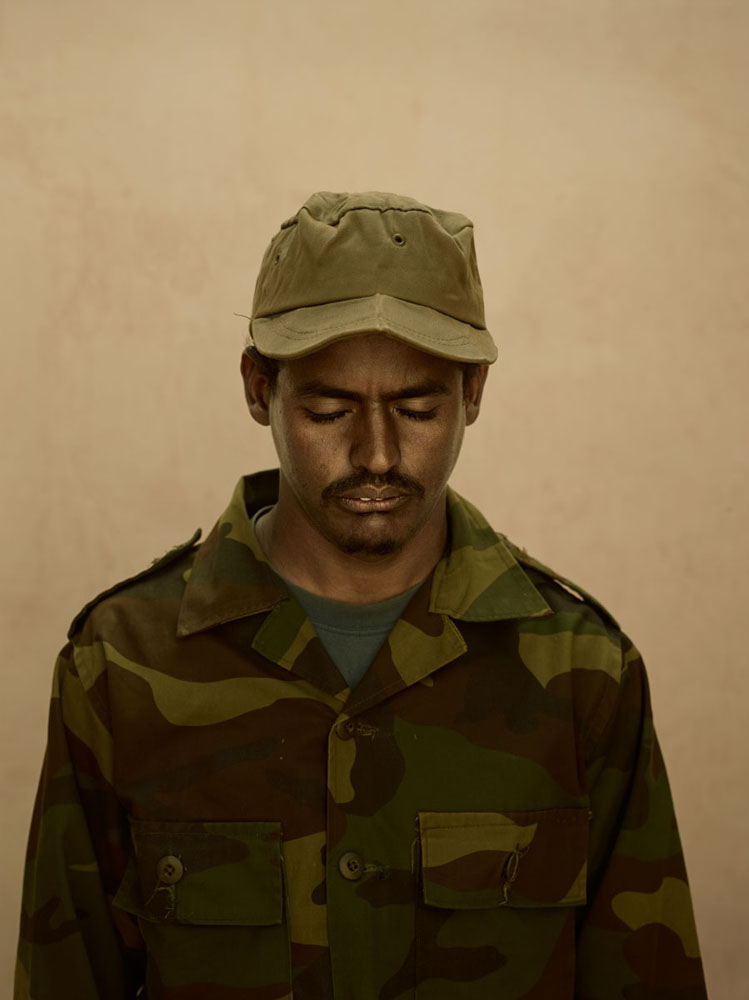

Olivier Laurent: There are three different sets of images in your work – two that focus on the toy nature of these soldiers, and one that are close-up portraits of them. Why that last set?

Simon Brann Thorpe: The portraits were an essential element to the project because at the center of this conflict — like all conflicts — you have the humanity, the vulnerability that is the human flesh. It also personified the project and added an essential human element that negates the objectification that is the association to plastic toy soldiers. A key element in the narrative of the project is around our objectification and desensitization to war through entertainment. To counter that, the portraits show the human at the centre of war and conflict, their eyes closed emphasizing their human vulnerability and loss of identity.

Olivier Laurent: In the end, the book brings together fact and fiction. Do you think this approach is helpful in bringing attention to stories that might not, otherwise, interest the public? Is it an approach you would like to see used more widely in documentary photography?

Simon Brann Thorpe: Toy Soldiers is an attempt at a new dialogue on war and conflict, a dialogue whose narrative asks many questions of how images of war are digested and consumed. Especially now in the digital age, which is ravenous for content but short on attention spans. What are the consequences of ubiquitous images of suffering? Do they desensitize an audience? And what makes one conflict more “newsworthy” than another? What the reaction to Toy Soldiers has shown me is that actually a conflict that mainstream media has overlooked or ignored, for whatever reason, actually can have huge resonance with people all over the world when looked at from a different angle.

Simon Brann Thorpe‘s photobook Toy Soldiers is published by Dewi Lewis and available now.

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com