This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

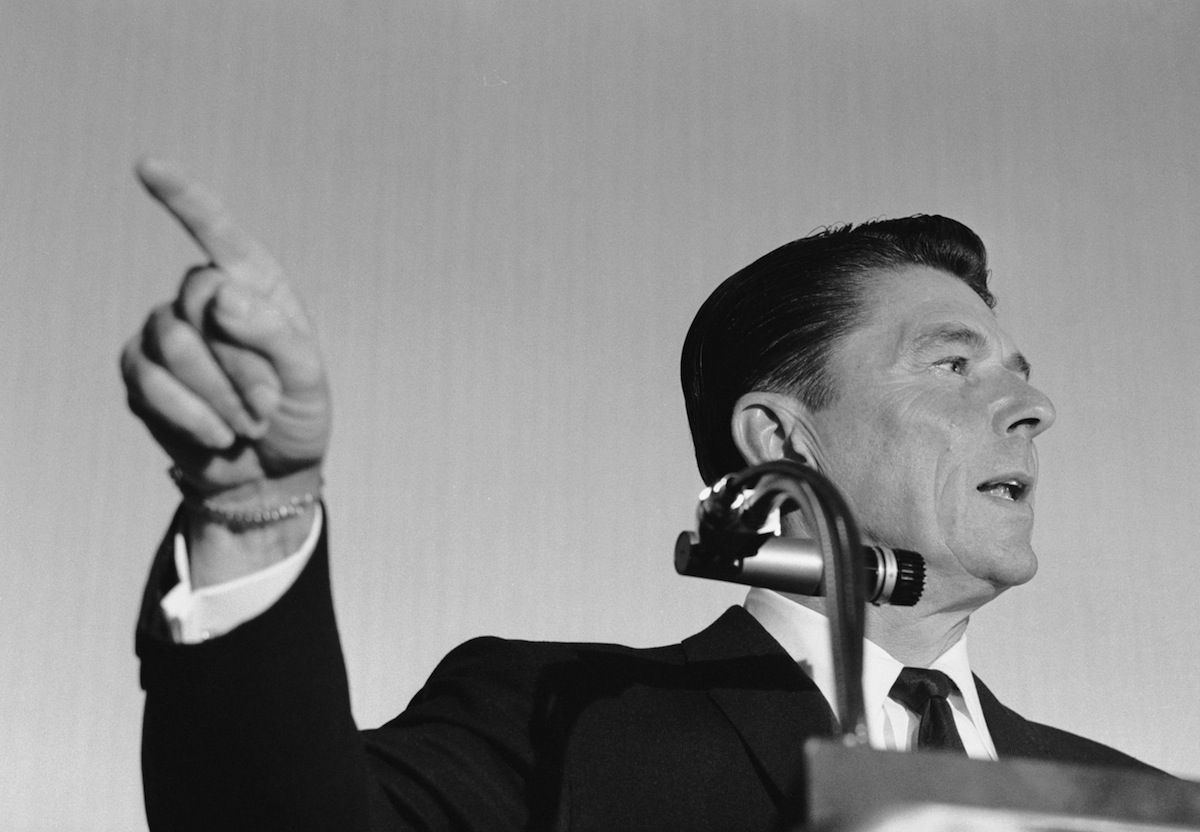

At the start of another Republican presidential campaign, we can be assured that the candidates will at some point express their fidelity to the spirit Ronald Reagan. And yet this fidelity, often bordering on reverence, is largely unjustified. For it is an inconvenient fact about Reagan that he was a failure when judged on his own policy terms.

Reagan came into public life as a deficit hawk and a crusader for smaller government. Starting with his first public political address in 1964, he constantly bemoaned the large deficits, the growing national debt, and the creeping inflation of the era as evidence that the United States had lost its way. In 1975, when he decided to challenge Gerald Ford for the Republican nomination, Reagan laid out his policy solution to address the crisis. He looked forward to, in his words, “a systematic transfer of authority and resources to the states.” By giving up federal responsibility for welfare, education, housing, food stamps, Medicaid, and community and regional development, Reagan believed that he could create efficiencies that would save the government $90 billion. That amount, he predicted, would be enough to pay down the national debt, balance the budget, reduce inflation through tax cuts, and prime the economy for further growth. With one masterstroke, he claimed to be able to solve all problems.

Although Ford had a field day with Reagan’s proposal and Reagan eventually lost the nomination, he never really departed from his fundamental belief that the nation’s problems had a simple solution. And after the campaign, when he was introduced to supply-side economics and the idea that you could grow the economy through the magic of tax cuts that would pay for themselves, he retrenched his policy vision in that new economic language.

But once in office, his vision ran into problems. In his first meeting with the cabinet, he told them what he most wanted was to “reduce the size of government very drastically.” His team mobilized to push through a $35 billion budget cut that was approved just before the July recess. With victory in hand, he then successfully promoted a massive tax cut that would occur in several steps. A 5 percent reduction was scheduled to begin on October 1, 1981, followed by an additional 10 percent reduction in each of the following two years. The Congressional Budget Office projected the cost at $180 billion over three years, but Reagan waved the concerns away. “Every major tax cut that has been made in this century in our country has resulted in even the government getting more revenue than it did before, because the base is so broadened by doing it,” he told reporters.

Unfortunately, rather than the expected boom in tax receipts, Reagan almost immediately faced huge deficits that grew into the biggest budget shortfalls in peacetime. Reagan’s budget director, David Stockman, began pushing to give back some of the tax cuts. But Reagan refused, complaining after one budget meeting, “I think Dave S. tells us more than we need to know for budget decisions.” But eventually he had to concede there was a problem. In 1982, as the size of the deficits became clear, he sadly admitted to his diary, “We who were going to balance the budget face the biggest budget deficits ever.” Still, he never took responsibility, consistently blaming the economy, the Democrats, the social welfare system, anything but his own policies.

Yet it was what he said in public that generated his true success—and the mystique that we still see today. Instead of admitting his failure and adjusting accordingly, he turned to another longstanding habit: sloganeering about the Founding Fathers. It turns out that he didn’t really care about the deficit or even smaller government, which also grew under Reagan largely because of his increased military spending. “Our real concerns are not statistical goals or material gain,” he told the Conservative Political Action Conference in 1982. What he wanted instead was a renewal of “‘the sacred fire of liberty’ that President Washington spoke of two centuries ago.”

And so, as his policy failures emerged, Reagan increasingly turned to the Founders to cover his shortcomings. His policies would no longer be measured in numbers or reality, but instead with the putative values of the founding generation. To those who criticized the deficit, he responded that he stood for “the dream conceived by our Founding Fathers,” which honored “individual freedom consistent with an orderly society.” He then varied that theme depending on audience. To the nation’s governors, he praised the fact that “Jefferson and Adams and those other far-sighted individuals” had created a “system of sovereign States” that was “vital to the preservation of freedom.” It was that system that he was working to restore. To evangelicals, he said that “the Founding Fathers were sustained by the faith in God” and had written that faith into the founding documents. Their religious vision was the basis of his policies. In response to Walter Mondale’s suggestion that taxes be raised to address the exploding deficit, Reagan claimed that Mondale saw “an America in which every single day is tax day, April 15th,” whereas he saw “an America in which every day is Independence Day, the Fourth of July.”

As strained gestures to the Founders took the place of reasoned analysis and debate, the Republican Party turned in on itself. The niceties of economics, the numbers that guide policy decisions, the trade-offs and choices inherent in governance—all these in Reagan’s Republican Party were beside the point. But the deficit never went away. When he left office, the debt had tripled under his tenure. The nation went from being the world’s largest creditor nation to being the world’s largest debtor, which it remains to this day. Taxes didn’t even go down much, except for the very wealthy. When he entered office, 19.4 percent of national income went towards taxes. Eight years later it was 19.3 percent. But because he cut so much in domestic spending (most of the increases were for the military), many state and local governments had to raise taxes, so the overall tax burden actually shifted upward.

These numbers tell a different story than you are likely to hear in the Republican campaign. But I suggest that we judge Reagan on these terms—his original ones—rather than falling for the propaganda.

David Sehat is an associate professor of history at Georgia State University and the author of The Jefferson Rule: How the Founding Fathers Became Infallible and Our Politics Inflexible (May 2015).

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com