The Hollywood Hills were a lucky place to land, close to the action but removed enough to be peaceful, with piney air and lots of tranquil corners conducive to yoga and meditation. Adjusting to a new life in America, Eugenia Peterson would depend on both. Contrary to what she’d been told, there was no yoga studio awaiting her. She had no job, no family in the country, and no homeland to return to. She was nearing fifty in a city that worshipped ingénues. She had $6,000 in savings—a substantial amount in 1947, but hardly enough to live on. “The only thing left to do,” she writes, “was to begin anew.”

The fact that Eugenia had so few connections meant she could finally shed her old identity once and for all. Hollywood was a place where people regularly swapped the quotidian names they were born with for more melodious or sophisticated or exotic ones. Many of the people who would become Eugenia’s most illustrious students had jettisoned the names their parents gave them—Jennifer Jones was born Phyllis Isley, Ramon Novarro was originally José Ramón Gil Samaniego, and Greta Garbo had been Greta Gustafsson. In Los Angeles, Eugenia could finally and fully become Indra Devi. Few in America knew her as anything else.

Devi made little effort to contact those who did. Upon arriving, she doesn’t seem to have looked up her old master Krishnamurti, which is in some sense surprising—after all, she’d once traveled halfway around the world just to be close to him. A person reinventing herself, though, doesn’t always welcome reminders of the past. Krishnamurti knew her as Eugenia, the Theosophist and lovesick diplomatic wife, not as an experienced yogini, as women practitioners of yoga are sometimes called. Besides, while Devi was a warm person, she also had a starkly unsentimental side. When a chapter of her life closed, she rarely tried to revisit it, so that people who knew her in one incarnation heard little about those who populated her earlier lives. Leaving the past behind was both a spiritual philosophy and a survival strategy, allowing her to thrive in the midst of calamitous instability. She was generally happy to see people she’d known before, but she didn’t seek them out.

In the 1990s, Devi traveled to Moscow to give a talk, accompanied by David and Iana Lifar, the Argentine couple who were her constant companions during the last years of her life. A woman came to her hotel claiming to be the daughter of a cousin of hers, which, if true, would have made her Devi’s only known living relative. The two talked for a while, and Devi gave her some money, because she seemed to be quite poor. After forty-five minutes, though, Devi called David and Iana and said that she wanted the woman to go, but she wasn’t taking the hint. Iana, who speaks Russian, came and urged her out. The woman was quite upset, telling David and Iana that she hadn’t wanted money; she’d wanted to spend time with her “aunt Zhenia.”

At breakfast the next morning, David asked Devi why she’d been so eager to get away from the woman. “David,” she told him, “I try to live in the eternal now. This lady belongs to my past.” She was, for the most part, kind toward those around her, but one of her main teachings, said David, “was not to be attached to anyone,” and she practiced it with only a few powerful exceptions.

So, in Los Angeles, rather than seek comfort in her history, Devi steamed forward, looking up Bernardine Fritz. Fritz had been a doyenne of society in Shanghai, where she’d hosted one of the few salons that brought expatriates together with Chinese artists and intellectuals, though she’d left China before Devi arrived. In Los Angeles, Fritz once again became known as a glittering entertainer, hosting Sunday lunches and cocktail hours in a hilltop home full of Chinese art. She threw a party to introduce Devi to her friends, including many who worked in Hollywood. They gravitated to the exotic newcomer with the saffron sari, eastern European accent, and Indian name.

Fritz was particularly close to Aldous Huxley, who, with his wife, Maria, was at the center of Hollywood’s literary and spiritual scenes. As a young British writer, Huxley, a tall and skinny sophisticate who, with his stooped posture and thick glasses, looked rather like a handsome praying mantis, had been famous for his arch skepticism. (One newspaper story about him was headlined “Aldous Huxley: The Man Who Hates God.”) Ultimately, though, he found a life of cultivated cynicism insupportable, and under the influence of his friend Gerald Heard, an Anglo-Irish writer who would become one of California’s New Age pioneers, he began experimenting with spirituality. (The critic William Tindall lamented Heard’s influence on Huxley and mocked their life in California, where, “when they are not walking with Greta Garbo or writing for the cinema, they eat nuts and lettuce perhaps and inoffensively meditate.”) Yogic meditation helped Huxley break through a debilitating writer’s block. By the time he arrived in the United States for a pacifist lecture tour on the eve of World War II, he was convinced that only spiritual renewal could head off global annihilation.

Though their American sojourn was meant to be temporary, Aldous and Maria ended up settling in Hollywood, where he tried to capitalize on his literary prestige by writing for the movies. They became part of a circle that included Garbo, Charlie Chaplin, Anita Loos, and Christopher Isherwood.

Devi knew Huxley’s work, particularly his 1937 book Ends and Means: An Inquiry into the Nature of Ideals. She’d quoted it at length in Yoga: The Technique of Health and Happiness: “The ideal man is the non-attached man; non-attached to his bodily sensations and lusts; non-attached to his craving for power . . . non-attached to his exclusive loves . . . not even to science, art, speculation, philanthropy.”

It’s a sign of how quickly Devi moved to the center of things that, soon after arriving in America, she was invited to spend a weekend with the writer and his wife. All that she recorded of this visit is that they discussed health food—Maria warned her that American produce is sprayed with poisonous pesticides.

Like many in Hollywood, the Huxleys experimented with their diets as well as their consciousnesses. “How can you expect to think in anything but a negative way, when you’ve got chronic intestinal poisoning?” asks the Buddhist Dr. Miller in Huxley’s Eyeless in Gaza, the 1936 novel that marked the author’s turn to the spiritual themes that came to dominate his work. In that book, the narrator, a stand-in for Huxley, moves from jaded libertinism to a desultory stab at guerilla revolution before his encounter with the enlightened doctor saves him. The doctor lectures him on “the correlation between religion and diet . . . The fact is, of course, that we think as we eat.”

Everywhere in the emerging New Age culture was an assumed connection between health and salvation. That link, of course, is at the heart of modern hatha yoga’s power. (It exists in evangelical Christianity, too, but the cause and effect are reversed: salvation can lead to health, rather than vice versa.) Yoga as it eventually came to be practiced in the United States elevates exercise into a sacrament, merging the contradictory quests for beauty and selflessness. It’s a kind of secular magic, promising that by assuming certain physical positions, you can bring about specific changes in the body and soul—clearer skin and clearer thoughts. It’s alchemy for a disenchanted age, rendered plausible to Westerners by translating esoteric tantric terms into the language of glands and hormones. Yet, until Devi arrived, no one in Los Angeles was teaching it.

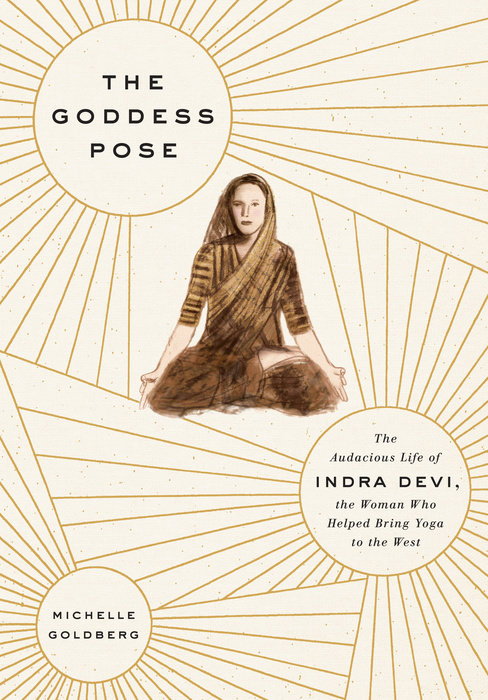

Michelle Goldberg is a senior contributing writer for The Nation and the author of the new book Kingdom Coming: The Rise of Christian Nationalism and The Goddess Pose: The Audacious Life of Indra Devi, the Woman Who Helped Bring Yoga to the West, from which this piece was adapted.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com