For more than a quarter of a century, while China censored and suppressed all mention of the event, Hong Kong has defiantly commemorated the anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre that took place in Beijing on June 4, 1989, when soldiers brutally crushed a weeks-long pro-democracy protest. Ever since, tens of thousands of Hong Kong people have gathered for the annual candlelight vigil at the city’s central Victoria Park.

This year, however, the normally sacrosanct unity represented by the vigil is being threatened because some of the student groups that have traditionally attended the event are deciding to opt out of it.

Most prominent among those is the Hong Kong Federation of Students (HKFS), which announced in April that it would give this year’s vigil a miss because many of its members do not believe in the demand for a democratic China that vigil organizers normally make. The reasons are partly to do with identity — many local students considers themselves to be Hong Kong people first and foremost, linguistically and culturally distinct from mainland Chinese. But there are also tactical considerations: many within the HKFS, one of the organizations at the forefront of the city’s pro-democracy movement last year, believe that they must focus on their own struggle for the right to elect the leader of this freewheeling, sophisticated city of just over 7 million mostly well-educated inhabitants.

“Trying to build a democratic China without having democracy in Hong Kong is utterly unrealistic,” Billy Fung, president of the Hong Kong University Students’ Union, told the New York Times. The student union, which recently followed several other universities in breaking away from HKFS, will organize its own gathering at the university campus on Thursday to “discuss Hong Kong’s future as Hong Kong people.”

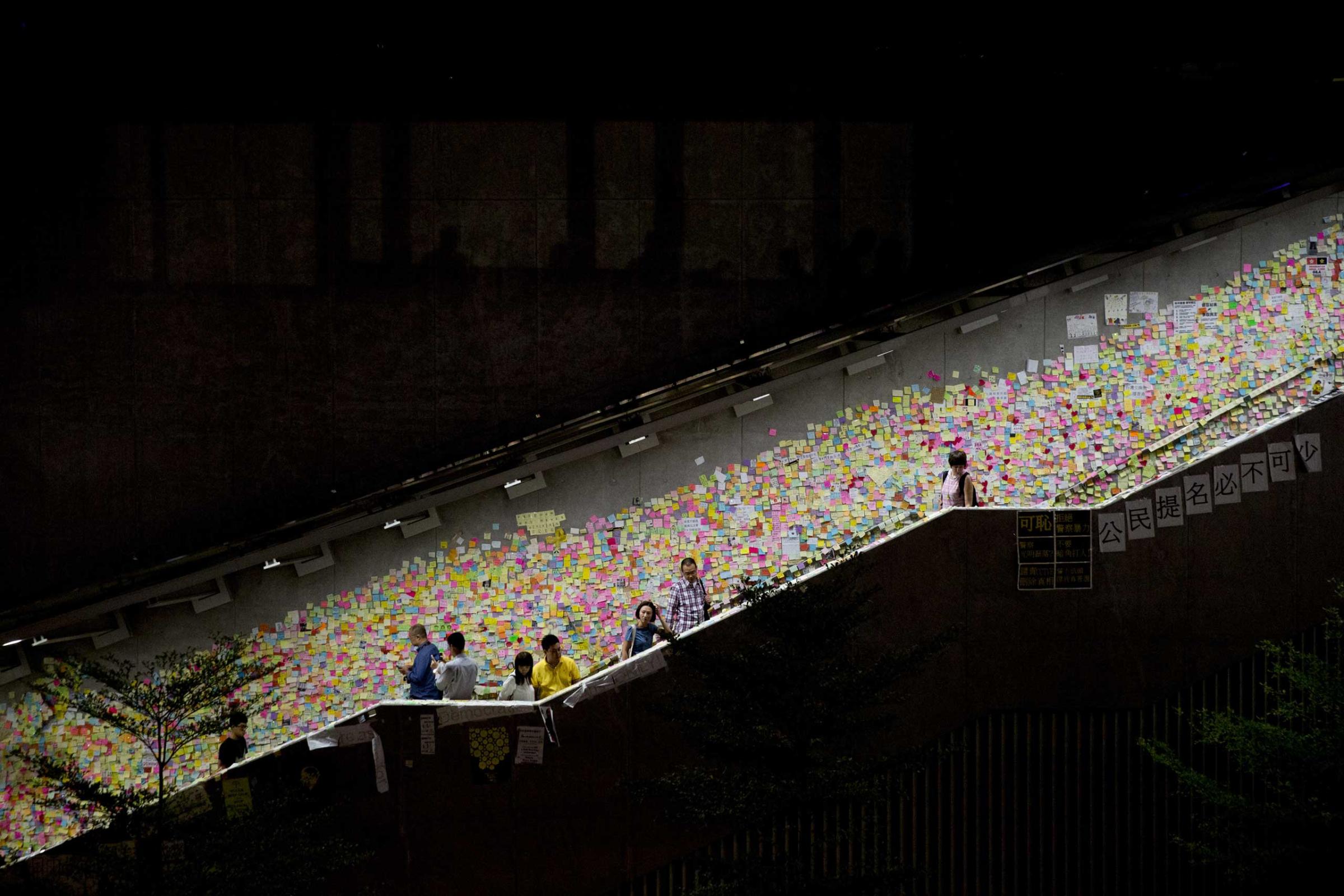

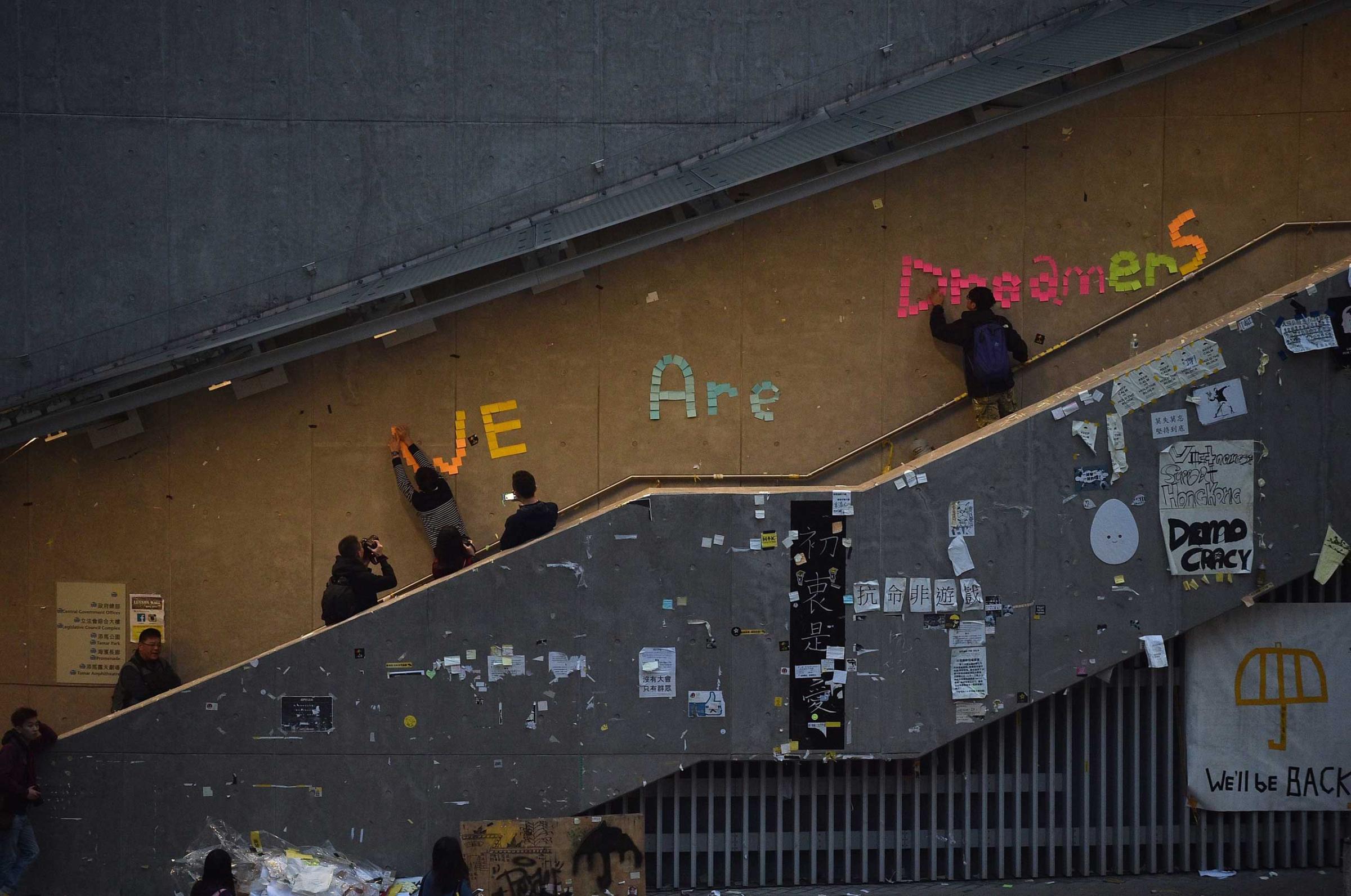

Unlike the brutal crackdown in Tiananmen Square that saw hundreds if not thousands of nonviolent Chinese protesters killed by the army, the tens of thousands of Hong Kong students and activists who occupied the streets for nearly three months last year were cleared peacefully in mid-December. The political reform they were campaigning for — the right to nominate and directly elect candidates for the city’s top job — remains elusive, however. The city’s present chief executive, as the leader is called, is Leung Chun-ying, who assumed office after winning just 689 votes from members of tightly vetted electoral college of mostly pro-Beijing and establishment figures.

79 Days That Shook Hong Kong

“The students find it difficult to realize the slogan of the organizers — ‘To promote democracy movement in China,’” Ho Pui-yin, a professor of modern Chinese history at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), tells TIME. “If they promote the democracy movement, they want to concentrate on Hong Kong.”

Student groups are not the only ones boycotting the event in Victoria Park. Another vigil is being organized by a group called Civic Passion set to take place across the harbor on the Kowloon peninsula. This parallel event, which began in 2013, is part of a growing “localism” movement that calls for a more radical separation between Hong Kong and China. Another group, called Localism Power, disrupted the annual Tiananmen commemorative march on Sunday, the Standard reported, with about 20 members of the group engaging in verbal altercations with the marchers.

The organizers of the Victoria Park vigil, a collective of several civil-society groups called the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China, are doing everything they can to stress that the schism between Hong Kong’s struggle for democracy and China’s is unnecessary.

“They are not against each other, we should be working together,” said Mak Hoi-wah, vice chairman of the alliance, speaking to TIME Wednesday night while supervising the setup for the event at Victoria Park. Nearby, a group of volunteers unfurled a large banner depicting a candle in the shape of a yellow umbrella — the symbol of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests last year.

“The young people want immediate solutions to problems because they’re frustrated and angry, they resent the government’s measures in Hong Kong as well as China,” Mak said, adding that these feelings could be what have now prompted them to shun the peaceful and symbolic gathering at Victoria Park. “But we do think that is very important because more than 150,000 people are coming to Victoria Park every year. We stand firm together to show our solidarity and to hold people accountable, this is the way we show our muscle and show our power.”

For Professor Ho of CUHK, the very thing that sets Hong Kong apart from China is what makes commemorating Tiananmen here so important.

“It shows that ‘one country, two systems’ is still working, because this is the only city in China that can commemorate the June 4 incident,” she says, referring to the principle under which Hong Kong is allowed greater economic and social liberties despite being under the sovereignty of communist China. “The main difference is that we have freedom of speech, so this shows to the world that Hong Kong is different from the mainland.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Rishi Iyengar / Hong Kong at rishi.iyengar@timeasia.com