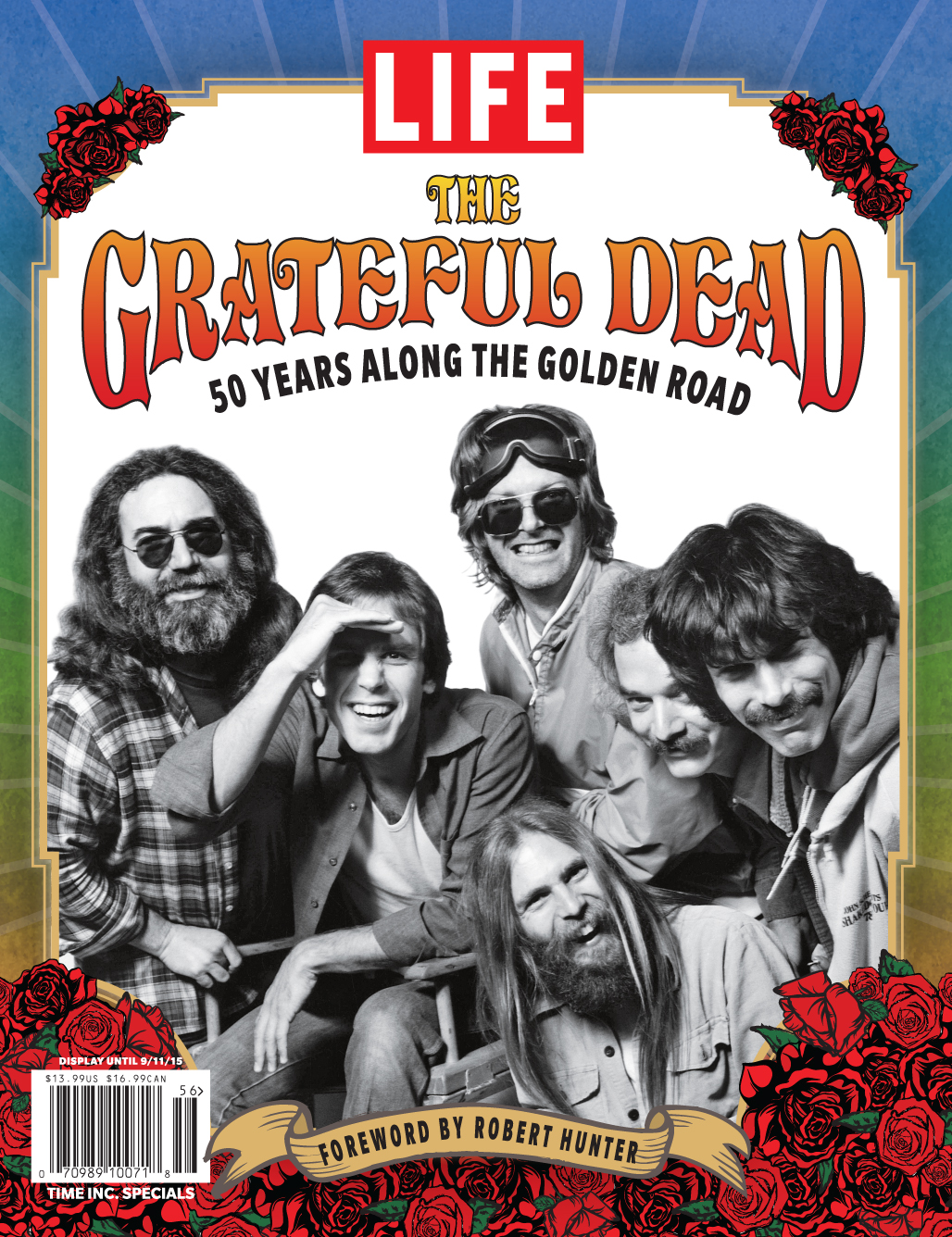

In LIFE’s new special edition celebrating 50 years of the Grateful Dead, Sally Mann Romano tells of her encounters with the band. Here is an extended version of that essay:

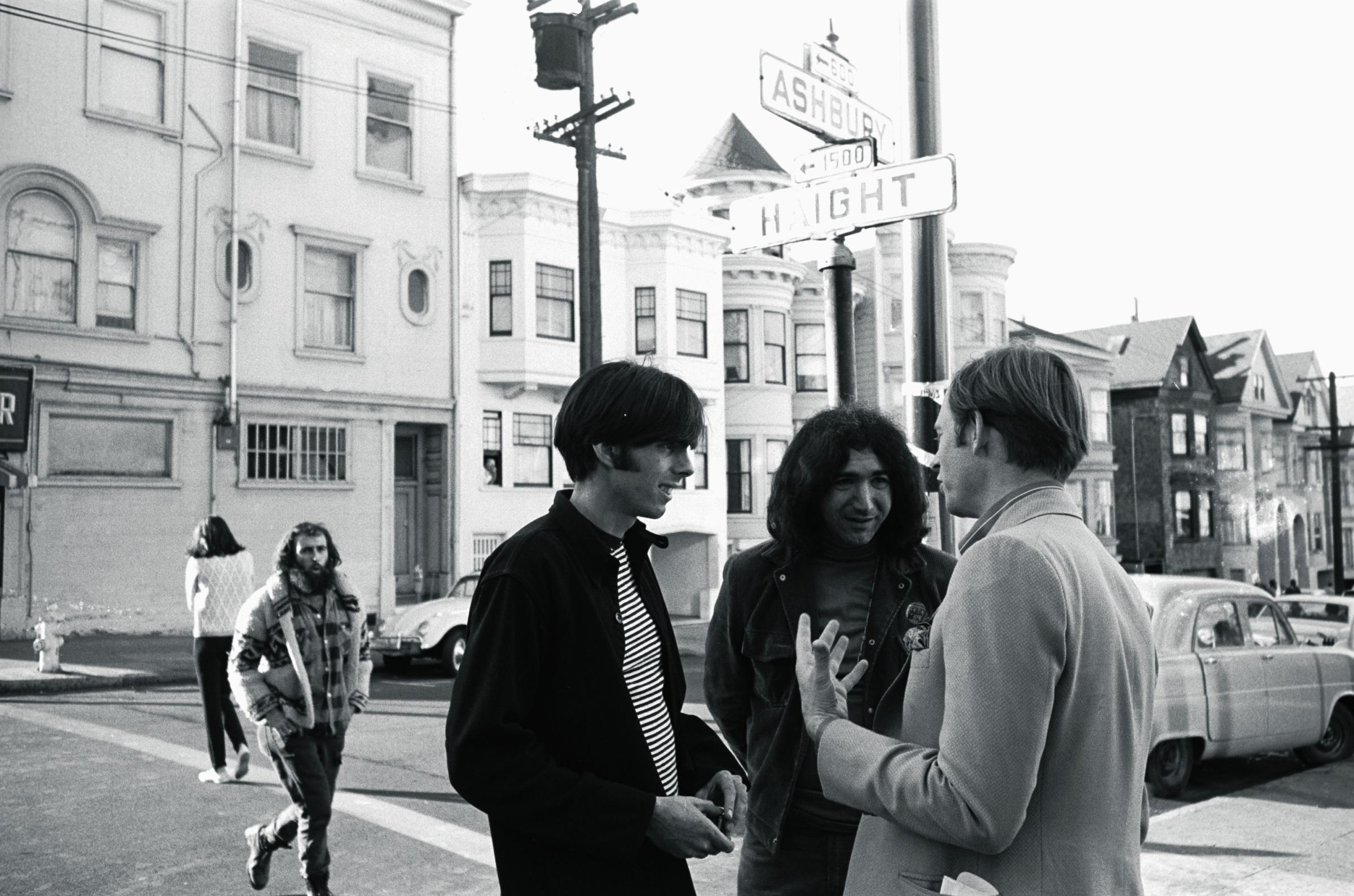

In 1968, after several glitter-smeared years in Hollywood pursuing a serious dramatic career in elite works like Where the Girls Are and Love on Haight Street with all the ardor I could muster while staying out all night on the Sunset Strip, simultaneously exhilarated and exhausted by the demands of serial social alliances, so to speak, with Frank Zappa, Phil Spector, John Mayall, and other similarly irresistible musicians with similarly modest egos, I was persuaded to head north to San Francisco. I landed at Tiffany Mansion at 2400 Fulton Street, the new-ish residence of my former short-term L.A. lover and permanent ace boon companion, Paul Kantner, Jefferson Airplane’s kamikaze rhythm guitarist. Before long, as such things were wont to go in the overripe afterglow of San Francisco’s Summer of Love, Paul introduced me to Spencer Dryden, the Airplane’s celluloid-ready drummer. After one afternoon with Spencer exchanging commodities of approximate commensurate value, in keeping with my history of protracted deliberation concerning affairs of the heart, I was a goner.

Immediate mutual attraction notwithstanding, the course of true love never did run smooth, at least in my case, and before I could seal the deal with Spencer, I faced the daunting challenge of sweeping up the sticky-sweet residue left behind in his heart by my predecessor, the formidable Grace Slick—an undertaking made appreciably easier by Grace’s waning interest in Spencer and growing interest in Paul. Timing is everything, and, for once, mine was fortuitous. Along with the rest of the band, we managed to spend almost the entirety of 1969 on the road together without killing (or impaling) each other, staggering from airport to godforsaken airport, from gig to gig—traveling to Honolulu, Chicago, Los Angeles, Boston, New York City, and many more prosaic stops in between—playing anywhere the rock-and-roll rabble could be counted on to congregate in mass quantities in those halcyon days. Before the bone-numbing sameness of Midwestern terminals with their revolving day-old hot dogs and the maddeningly ubiquitous, stupefyingly unoriginal commentary of “Is that a boy or a girl?” had combined to diminish my enthusiasm for nonstop touring, I was thrilled to be on the road with the Airplane.

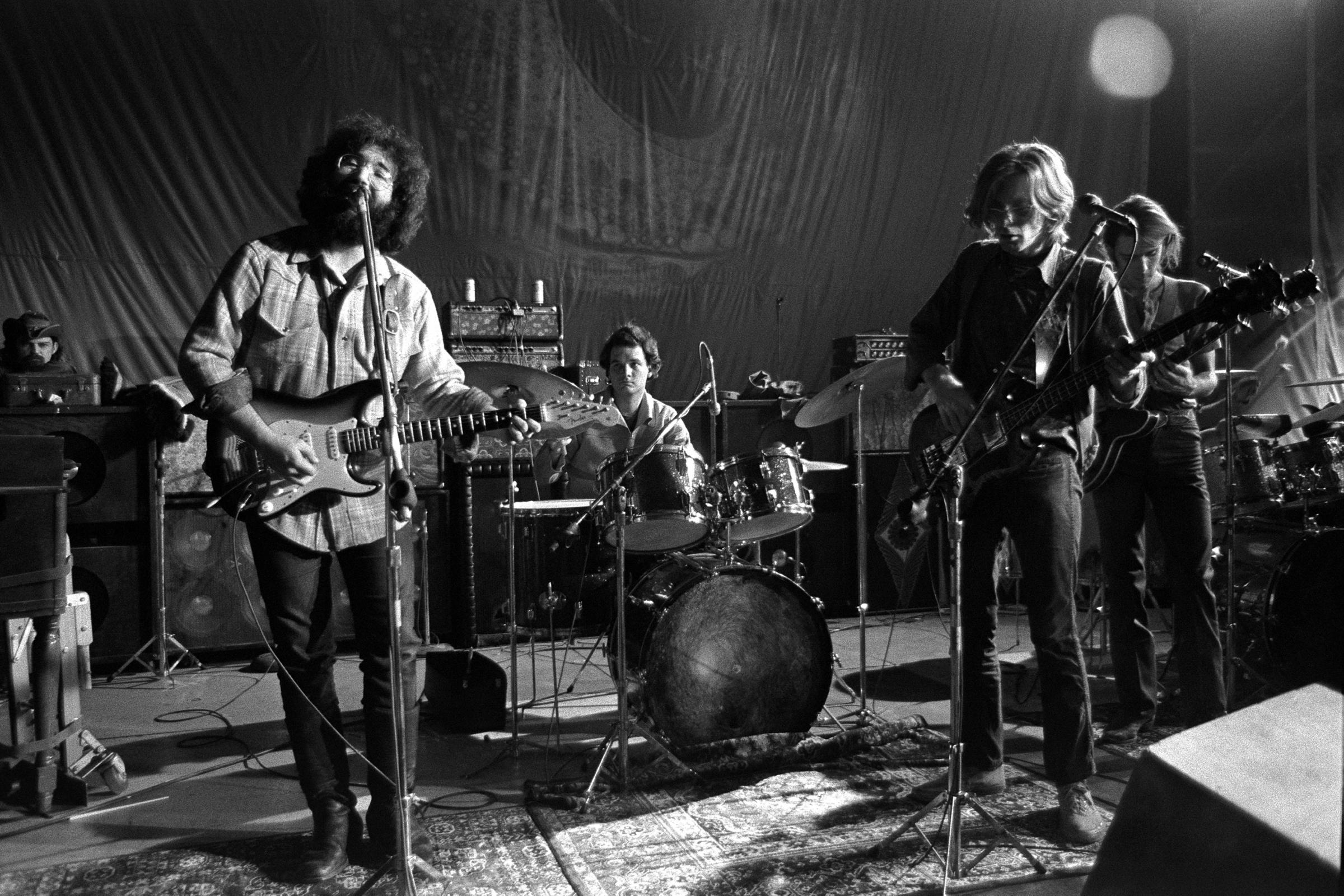

I was particularly excited about the Airplane’s gig in Houston, my hometown, where the band was booked for a huge show at the Sam Houston Coliseum on October 5, 1969, with Hot Tuna, Poco, The Byrds and the Grateful Dead (with Ken Kesey on harmonica in case the line-up wasn’t already radioactive enough). It would not be an overstatement to say that, on the whole, Houston’s municipal authorities were not overly avid about the invasion of their God-fearing burg by a passel of unrepentant guitar-slinging vipers and their gaudy camp followers with too much face paint and too few morals, all of whom were hell bent on pushing their loathsome acid rock on Houston’s tender innocents.

Every police officer in Houston not working a funeral procession had evidently been called out for the show, and they were in no way reticent about making their beefy presence felt, preening in front of the stage and hanging from the rafters in full gold-braid regalia. Not to be outdone, the Houston Fire Department was onstage in force, manning the breaker boxes and loaded for bear, fully prepared, if not eager, to shut the show down at the slightest provocation. (With my uncle being Houston’s former Fire Commissioner and a current city councilman, I took the Fire Department’s ominous presence as a personal slight.) According to the antiquated Coliseum’s equally antiquated Fire Code, the assigned-seating, maximum-capacity crowd of excitable fans was not permitted to dance, stand in the aisles, or even toss off a half-baked upper-body shimmy to “Somebody to Love” in front of their seats—all fiercely unwelcome restrictions that put quite a damper on the general joie de vivre of the Love-In. And thus it was that the rebellion began to foment.

As far as Kantner’s volatile sensibilities were concerned, blue uniforms were like a flaring red cape to a thrice-gored bull still smarting from the banderillas. Very little in this world, if anything, pleased Paul more than pissing off the Powers That Be—especially in a hopelessly out-of-it hinterland (to his way of thinking) like Houston. So, naturally, Paul exhorted his highly receptive audience to defy the Fire Marshal’s bull-horned orders in all their flaming stupidity, rise up off their collective thang, and dance, dance, dance to the thunderous music. In row after row, the revolutionaries-manqué exuberantly complied—until, that is, there was no more music, thunderous or otherwise. Not surprisingly, the HFD had pulled the plug with amazing alacrity—first on Paul’s microphone and then on the mains—and Paul once again found himself in the warm embrace of a local constabulary, cheered on as a hero of the revolution by a howling crowd of thousands. This entire psycho-trauma performance-drama ended with the Dead and the Airplane (those of us who were not in custody) right back at Houston International Airport somewhat sooner than reflected on our itineraries, under explicit orders to get out of town before sundown.

When Spencer and I arrived at the airport’s main restaurant, desperate to pass some time unaccosted before our flight, things failed to improve. The Grateful Dead, including their jitter-buggy brown-eyed road manager and my lifetime crush, Rock Scully, their entire crew of ne plus ultra roadies and technicians—and, of course, Augustus Owsley Stanley III (“Owsley,” underground chemist to the stars and pathologically obsessive sound engineer), whose job assignment on this trip was somewhat amorphous to say the least—were already sprawled out at the largest table in the dining room in all their tie-dyed glory (courtesy of The Master, Courtenay Pollock), silver aluminum Zero Halliburtons all in an understated, anodized row. For some months prior, Owsley had been proselytizing to his acolytes and anyone else he could corner about some typically weird Planet Nine dietary theory of his that mandated frequent consumption of only the rarest red meat (and by “rarest” I mean that with a good vet, the cow could have recovered), and in keeping with His Eminence’s nutritional guidelines, each person at the Dead’s crowded table had ordered the most expensive steak on the menu with firm instructions to an already dubious waitress that each order must be served extremely rare, or there would be hell to pay, or not pay, as the case might be.

Lo and behold, like everything else that day, the Dead’s food orders didn’t turn out as planned (quelle surprise), and when Scully and Owsley objected vehemently to paying for their food due to its improper preparation, the management felt just as strongly about summoning the police to see that they did. While this highly energized brouhaha was playing out before an audience of slack-jawed diners, Spencer and I were sitting at a nearby table by ourselves, heads down and minding our own, when out of the blue, another HPD officer approached us (truly, their numbers must have been legion), tapped me on the shoulder, and told me in no uncertain terms to pull up the front of my dress, cover the rest of myself, and “start acting like a lady.” As it turned out, some patron had complained that my spectacularly beautiful Holly’s Harp repurposed piano-shawl dress was too low-cut on the top and too high-cut on the bottom, and what with murders and violence in Houston being so comparatively inconsequential, the gendarmes thought it necessary to dial down the heat on my sartorial splendor for the public welfare.

This terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day finally ended with the offending bands being escorted—all the way to the ramp and right past my uncle’s official portrait hanging in the marble corridor of the airport—to a waiting United DC-6 headed out of town. Since then, I have made it a rule never to dine with, or anywhere near, the Grateful Dead in a public transportation hub more than 25 miles from San Francisco. One has to draw the line somewhere, and I’m drawing it at Walnut Creek.

Sally Mann Romano is an attorney in her native Texas. In the 1960s she was not a lawyer but sometimes needed lawyering-up after one of her several—make that myriad—associations with rock stars. No one remembers the day more colorfully. Her book, The Band’s With Me, with a foreword by Grace Slick, will be published by Jorvik Press in 2016.

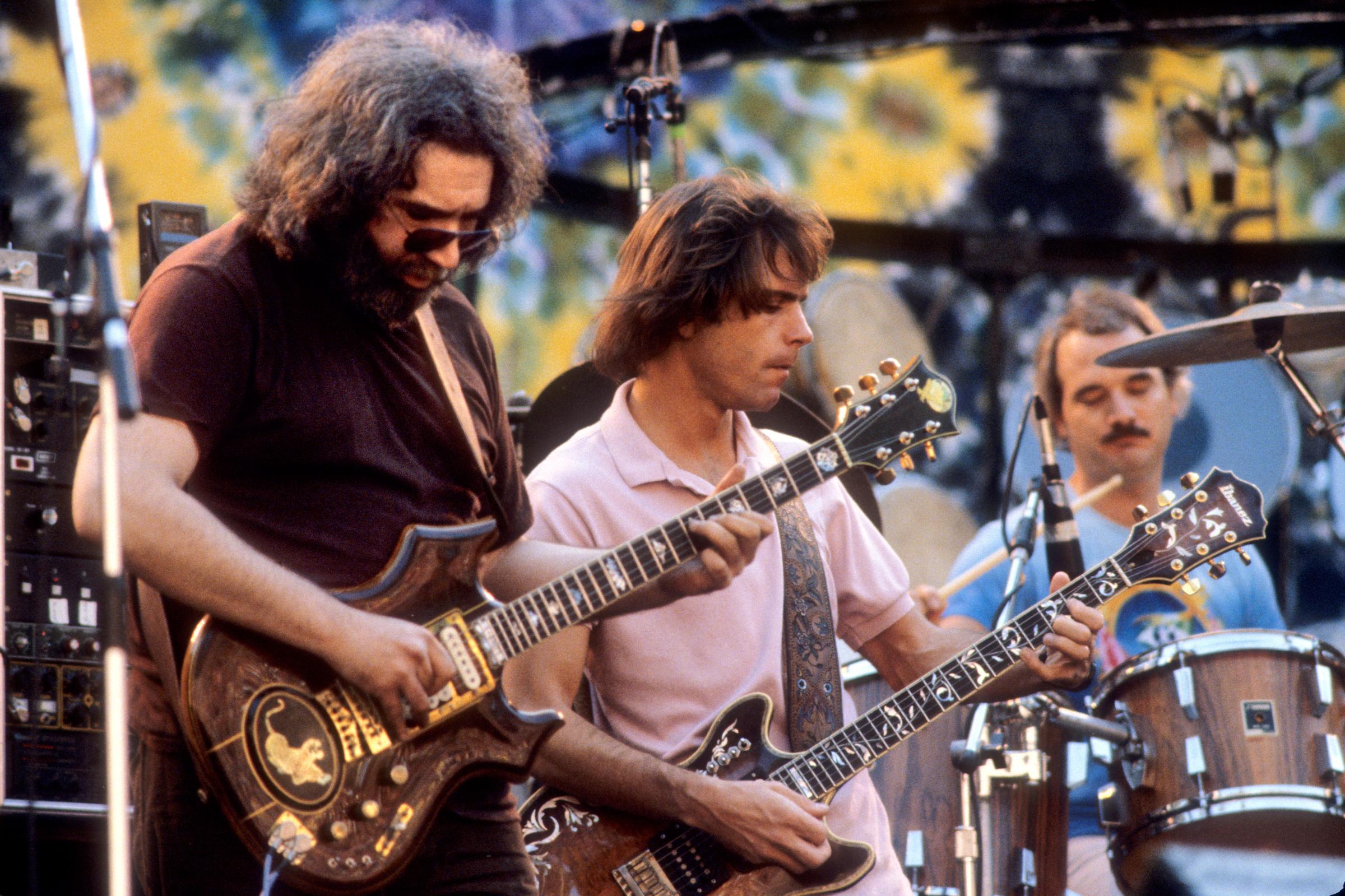

LIFE’s special edition The Grateful Dead: 50 Years Along the Golden Road is available in stores today. A digital edition is available at TimeSpecials.com

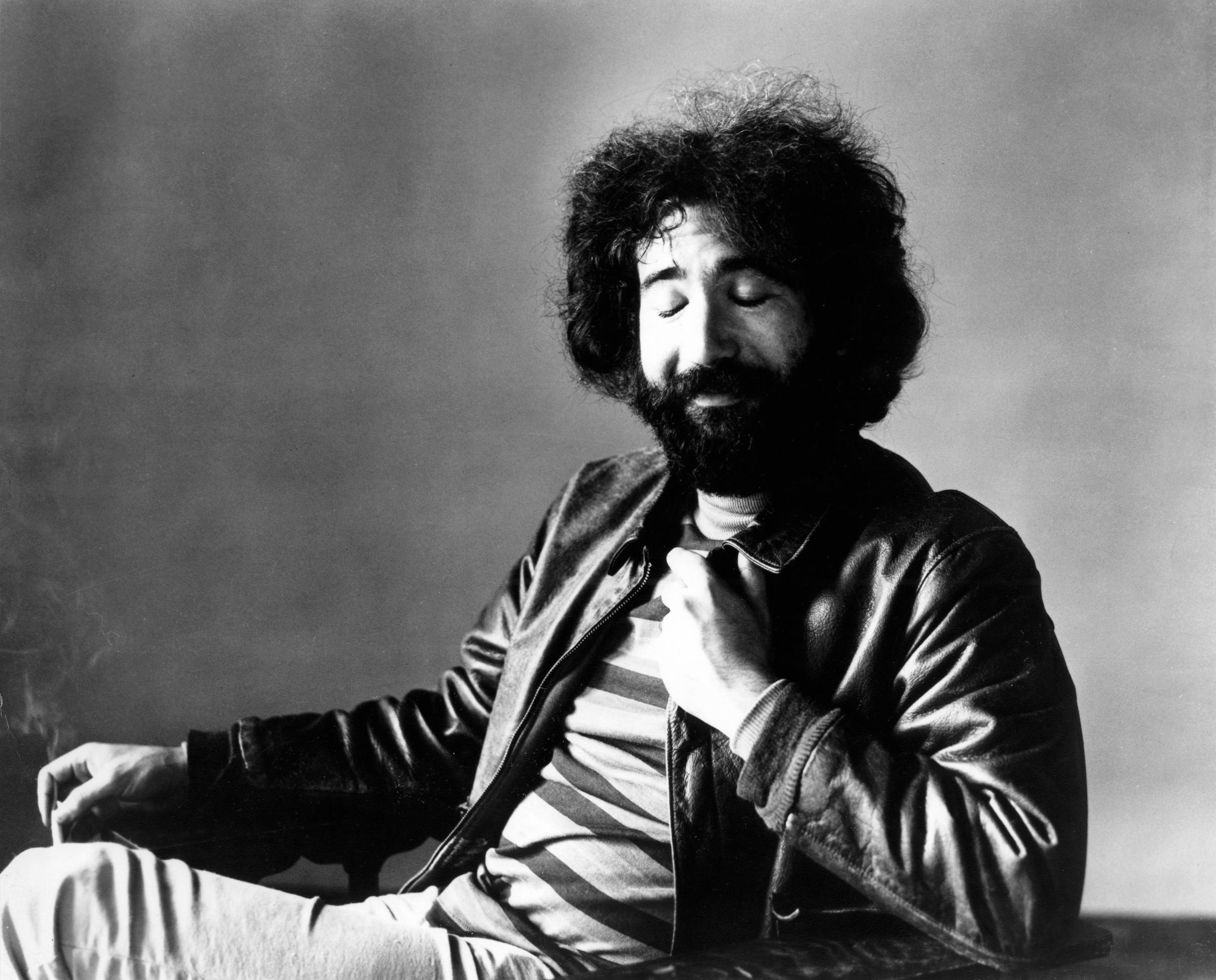

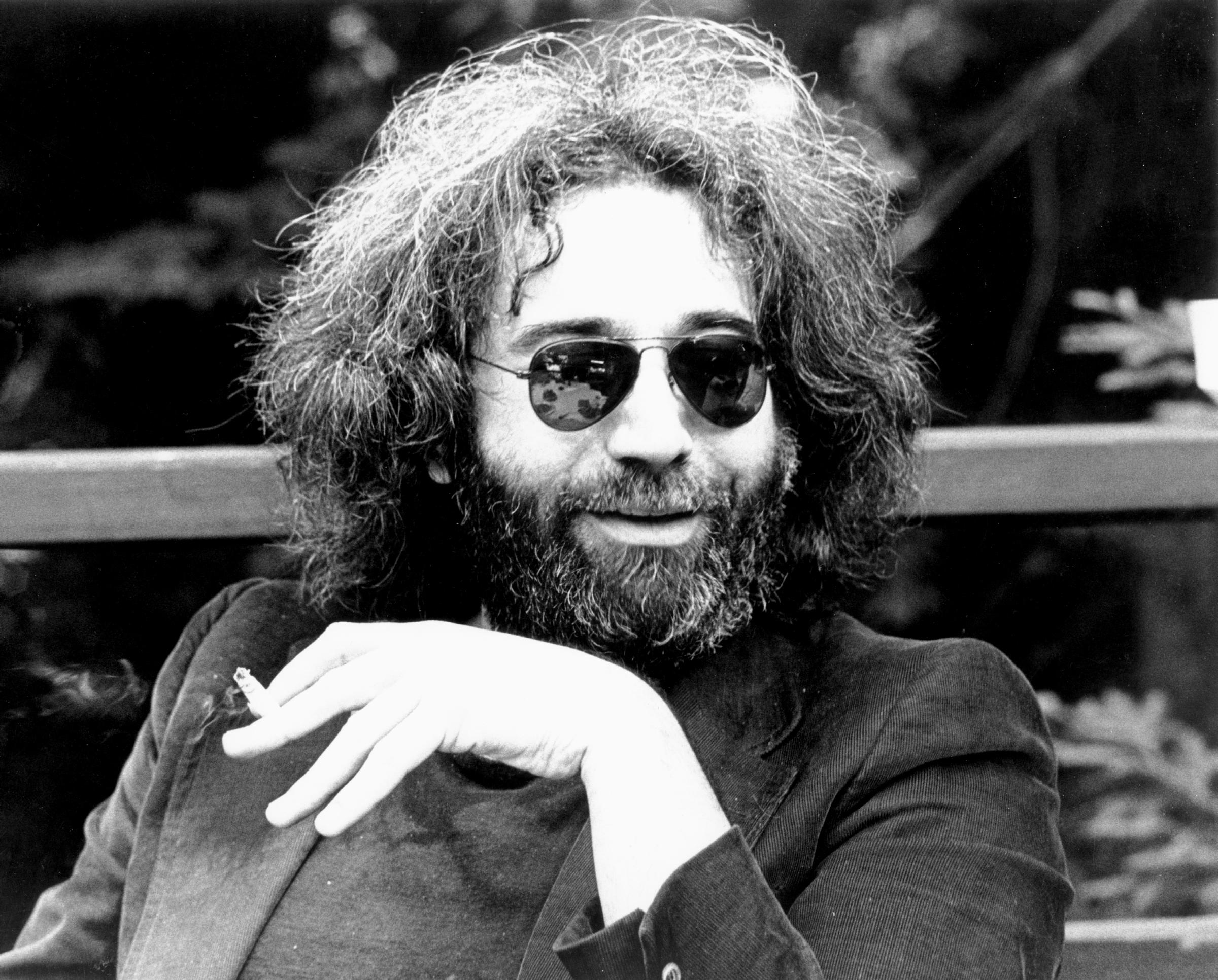

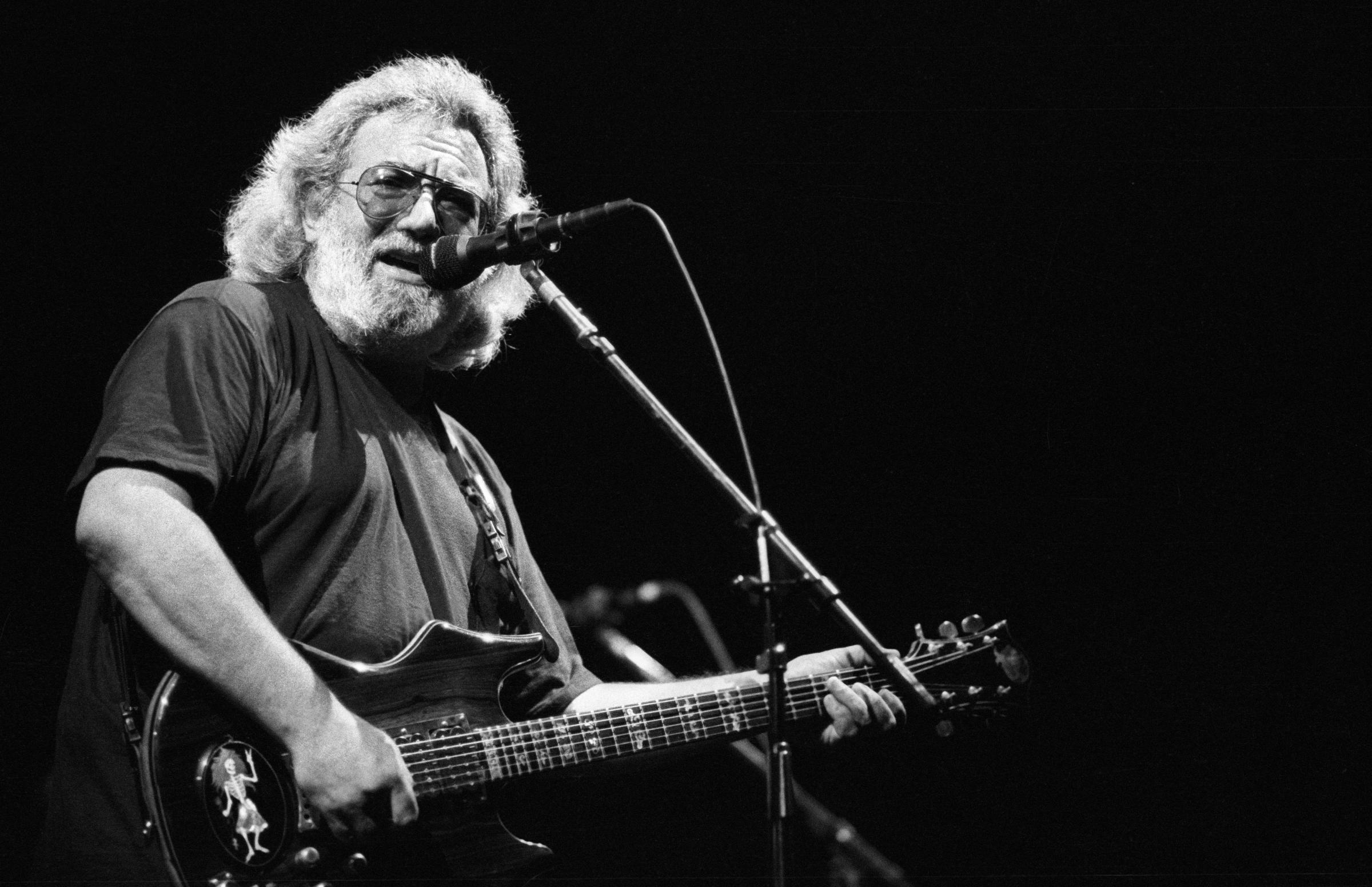

The Enduring Legacy of Jerry Garcia

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com