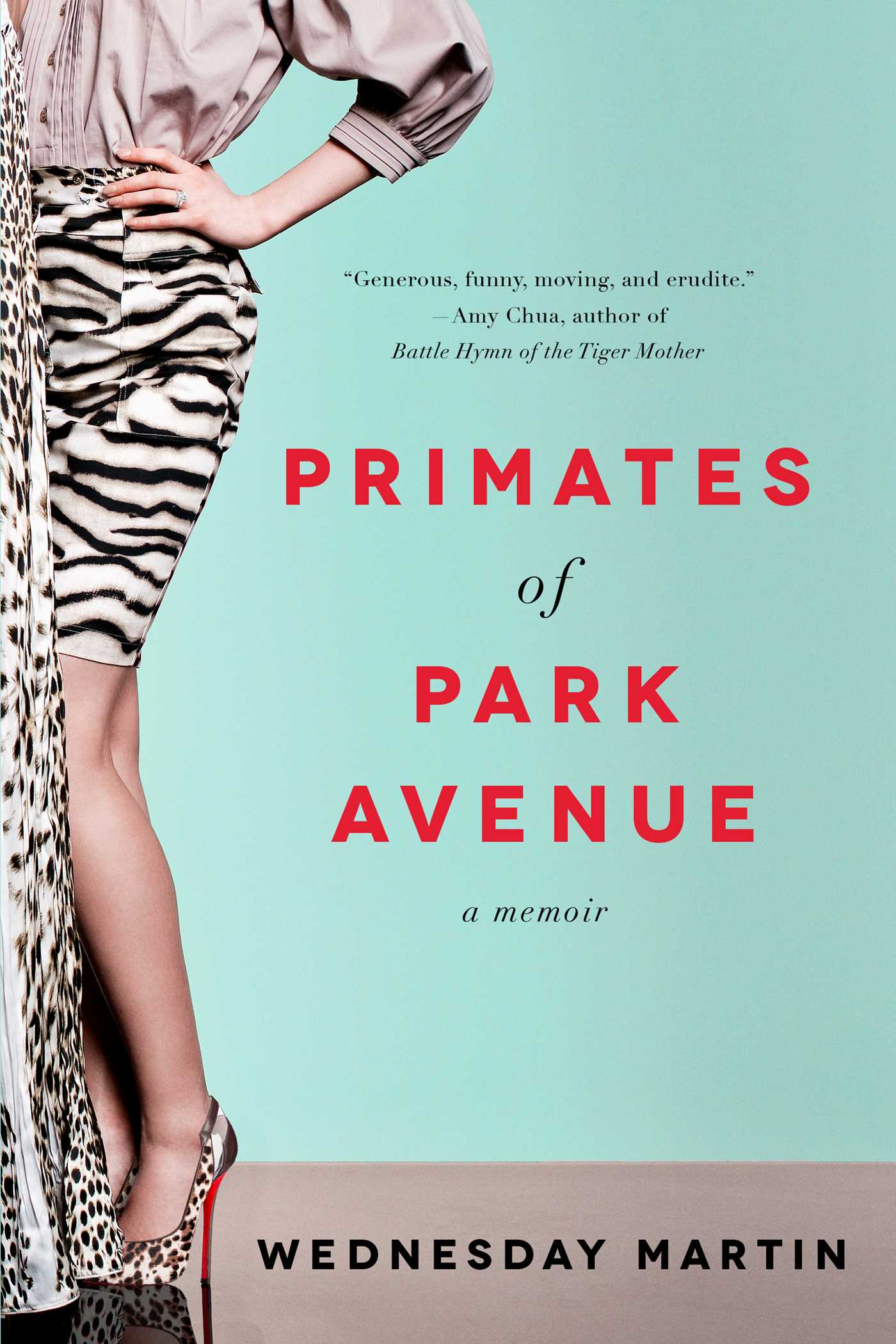

Wednesday Martin is the author of Untrue, Stepmonster and Primates of Park Avenue.

Nothing could be more foreign to the tribe I studied and lived among than giving up on their own personal upkeep—the zealous, dedicated striving to be a particular kind of fabulous, fit, and chic Manhattan Geisha with children. The type of women who get “wife bonuses.” But what was the point of all this effort, this endless fighting and trying and depriving and especially all this working on and working at our selves? It certainly wasn’t sex—you could call uptown a sexless Sahara.

The men on the Upper East Side and in the East End didn’t really bother to flirt, or hold doors open, or look at you the way men did in Rome or Paris or anywhere else in the world. In fact, the extremely successful men of the Upper East Side and the Hamptons always seemed a little distracted and bored, because they were—by the endless smorgasbord of stunning women all around them, all the time, preening and primping for their benefit. More than one European girlfriend remarked to me that men here seemed always to be looking beyond you, to see if there was a woman who was better or prettier or more important than you at the party or in the room. That was part of the reason we tried so hard, I suspected. The mixed-up numbers, the glut of beautiful young and young-looking-for-their-age women everywhere you looked, had changed everything about how men and women related in my world. Ratcheting up the display of their bodies, recourting their husbands and attracting the glances of other men was, conceivably, an attempt to cut through all the noise and make an impression on men who were utterly habituated to physical beauty.

And yet, this explanation failed to account for one of the most remarkable social realities of summer life on the East End. Like the Physique 57 and SoulCycle classes themselves, the whole place was astonishingly and comprehensively sex-segregated. Women came out in June, the second school let out, to set up house with the kids and the nannies. Husbands went back and forth on the weekends, but wives ran the show during the week. Everywhere you looked in the Hamptons, as far as the eye could see, there were women, women, women. Even when the men were there, the women of the tribe I studied often eschewed their company in favor of a girls’ night out or an all-women’s evening trunk show or a nighttime charity purse auction to benefit a school or battered-women’s shelter. At dinner parties I went to, it was not unusual for men and women to sit at separate tables, even tables in different rooms. In spite of all the hot bodies artfully displayed, there was not a lot of sexiness in the air. In fact, there was a remarkable absence of it. “Somebody had better flirt with me,” I used to say to my husband before we headed out for the night in Manhattan or the Hamptons. I was stunned by the lack of playful interactions between men and women. What, I wondered, was the point of life and having a body you worked on like crazy, if you didn’t have fun flirting? Utterly unlike geishas, the women I studied gave the impression that they were somehow above things like flirting. Like geishas, however, they were above sex. Sure, they had babies, so we knew they had had sex. But their bodies, put through such rigorous paces, tended to so meticulously, turned out so carefully, were purified and not for earthly pursuits.

In fact, the exercise and careful attention to dress seemed to take the place of sex in fundamental ways. Women were too tired, too stressed, too irritated for sex in Manhattan, they all seemed to agree when we talked about it over dinner or drinks. And once out here, removed from the stressors of the city, buffered by the beach and lovely weather, their kids in camp all day or even at sleepaway camp for weeks, rested and relatively happy, they were removed from men. The whole place put me in mind of a menstrual hut, and in fact we women all spent so much time together all summer long that our periods frequently synchronized. My identification with the tribe deepened with every exercise class and trip to the juice bar after, with every ladies’ luncheon and evening “event.” Compared with our girlfriends, our husbands were unfamiliar to us at summer’s end.

This, I learned, was their code. They strove equally to be beautiful for the men who were not there and for the women who were. They did it to bond with their fellow tribe members, but also to measure up to, and to take the measure of, others, day by day, evening by evening, event by event, class by class. They were like stunning red male cardinals, or breathtaking male peacocks, feathers spread, ready, always, to be seen. A beautiful, fatfree body and a forever-young face were prestigious “gets,” to be sure. But they were also requisite uniforms, a corporeal version of the grippy socks or handkerchief headbands women wore to class or the paddleboards they carted in the back of their Range Rovers. My body wasn’t exactly my own, it seemed to me at summer’s end. It belonged to the tribe, too. It was for working on and working at and improving, tirelessly, ceaselessly, endlessly, as hard as I could, for as long as I could stand it.

Read Next: What We Can Learn From Insanely Rich Parents

Wednesday Martin, PhD, has worked as writer and social researcher in New York City for more than two decades. She is the author of Stepmonster and Primates of Park Avenue.

Adapted from Primates of Park Avenue by Wednesday Martin, copyright ©2015 by Wednesday Martin. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com