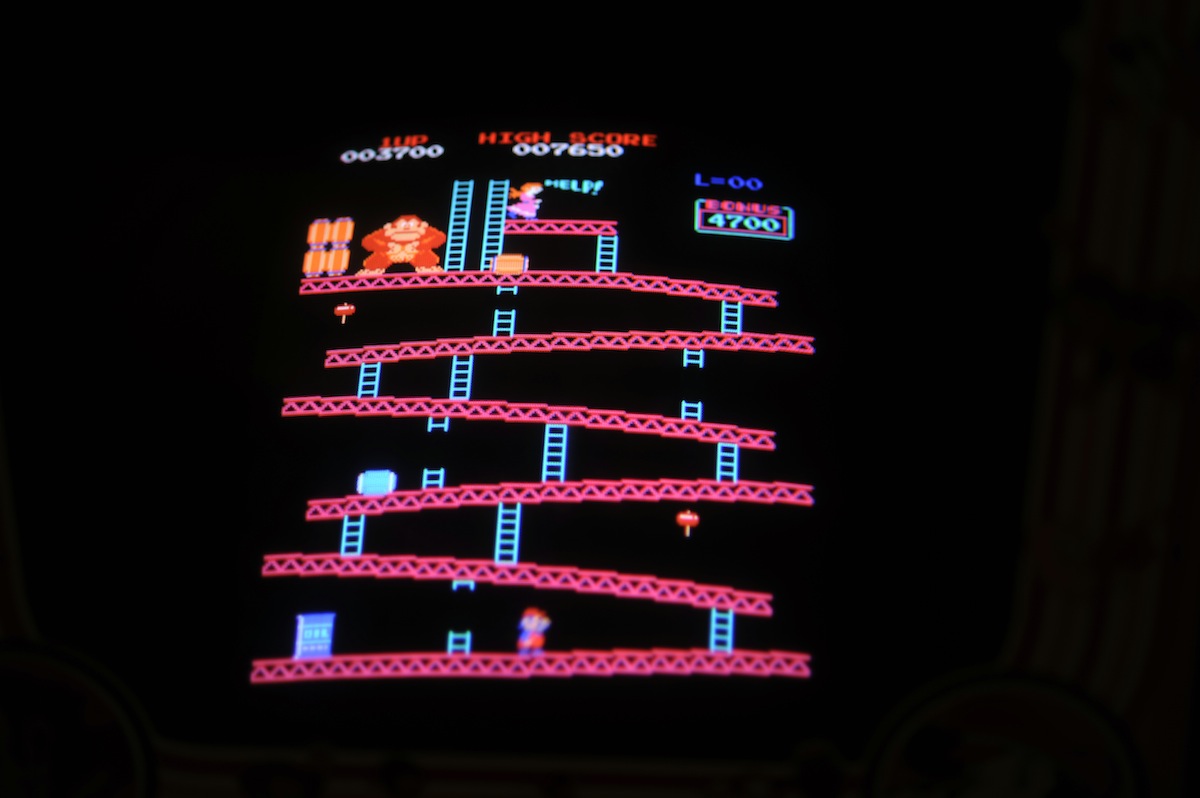

Before Mario was Mario, he was Jumpman. And when Americans first encountered him in arcades on this day, June 2, in 1981, Jumpman’s best friend — a pet gorilla named Donkey Kong — had turned on his owner, kidnapped his girlfriend and taken her hostage atop the towering steel beams of a construction site. It was up to us to help Jumpman get the girl, by coordinating his leaps from beam to beam while dodging projectiles lobbed by the furious gorilla.

Donkey Kong was a hit. It was also a milestone in video game history: the first of the so-called platform games, and one of the first to have a substantial narrative, along with a sense of humor, as Nick Paumgarten had written for the New Yorker. “Prior to Donkey Kong,” he says, “games had been developed by engineers and programmers with little or no regard for narrative or graphical playfulness.”

Its success cemented Nintendo’s role as a major player in the American video game market pioneered by Atari, following the dismal reception of Nintendo’s previous game, Radar Scope, a shooting game reminiscent of Space Invaders. Donkey Kong was a reversal of fortune that ultimately launched a line of games in which Jumpman came into his own as Mario, joined by his brother Luigi. And it helped usher in a new age of gaming — one that has since seen nearly as many ups and downs as Jumpman himself.

Following a surge of popularity in the late ’70s and early ’80s, video games started to get a bad rap — one they still haven’t quite shed — when worried parents began to see them as the undoing of the youth of America. By 1983, even before home gaming consoles were ubiquitous, video games had been blamed for “increasing crime and school absenteeism, decreasing learning and concentration, and causing a mysterious ailment called video wrist,” according to TIME.

The game industry countered the claims, arguing that video games promoted dexterity and quick thinking, and that arcades were a wholesome gathering place where young people could network and build social skills — the golf courses of the high-school set, per TIME. A University of Southern California researcher who interviewed arcade-goers for a 1983 study underwritten by Atari found that gamers tended to be “average or above average students [who] rarely played hooky from school,” and concluded that drugs and alcohol were not common on the arcade scene — if for no other reason than that they impaired players’ high-scoring abilities.

Atari and Nintendo had more to fear than parents’ concerns, however. The same year, video game profits tanked — thanks to “overheated competition, an oversupply of games, relentless price-cutting, plunging profits and a new finickiness among young video fans,” per TIME. The slowdown affected the glutted arcade market — which had more than doubled between 1980 and 1982 — and home video game sales alike.

Nintendo, powered up by Mario’s successes, largely managed to dodge the market’s profit-crushing projectiles. Atari, which lost $356 million and cut nearly a third of its payroll in 1983, did not.

Read more from 1983, here in the TIME archives: Video Games Go Crunch!

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com