Geopolitics can be child’s play—literally. How else would you describe the did-not! did-too! brawl that can result when one country crosses another country’s invisible line in the playroom that is the South China Sea? How else would you describe the G-8 canceling its playdate in Sochi after Russia climbed over the fence to Ukraine’s yard?

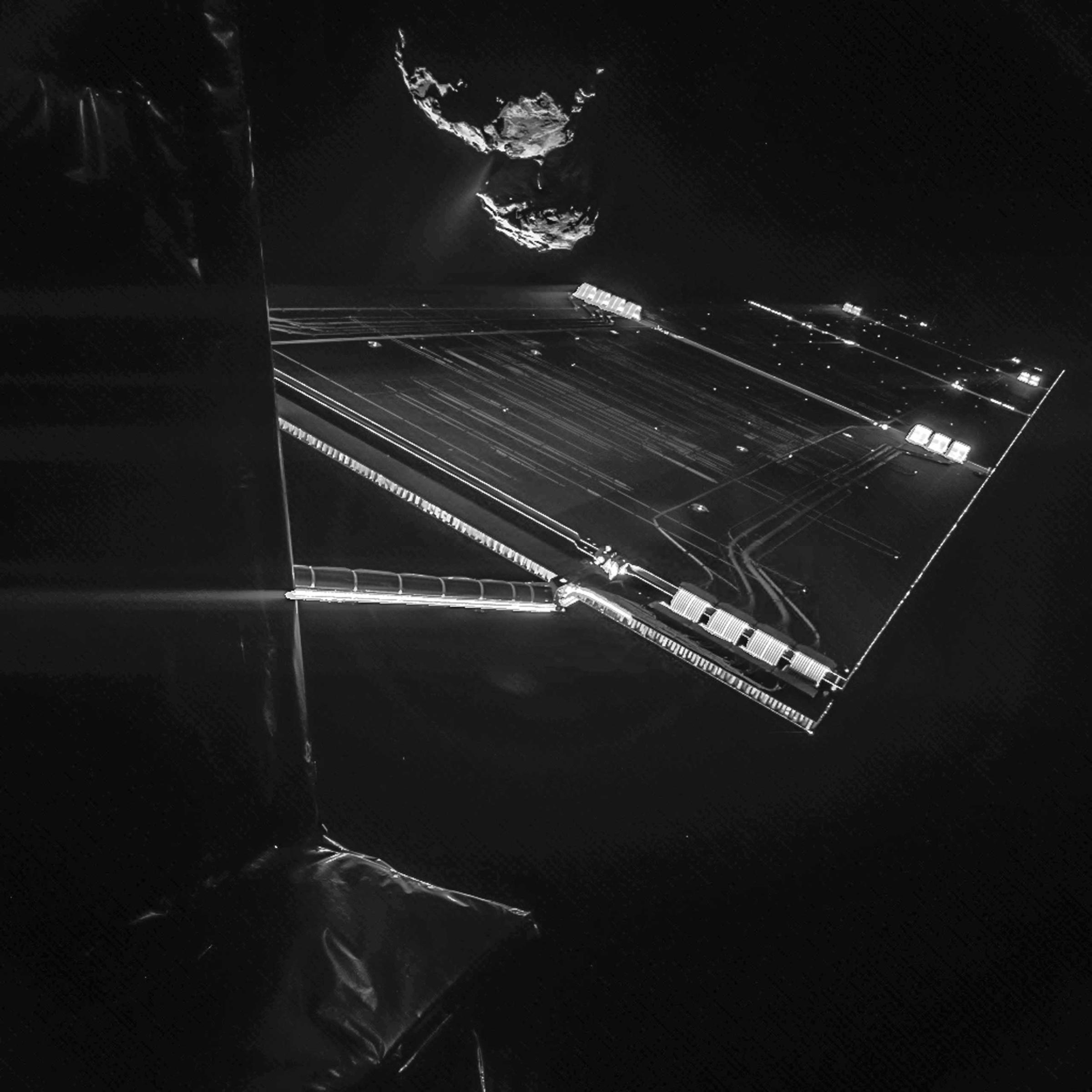

Something similar is true of the International Space Station (ISS), the biggest, coolest, most excellent tree house there ever was. Principally built and operated by the U.S., the ISS has welcomed aboard astronauts from 15 different countries, including such space newbies as South Africa, Brazil, The Netherlands and Malaysia. But China? Nuh-uh. Never has happened, never gonna’ happen.

China has been barred from the ISS since 2011, when Congress passed a law prohibiting official American contact with the Chinese space program due to concerns about national security. “National security,” of course, is the lingua franca excuse for any country to do anything it jolly well wants to do even if it has nothing to do with, you know, the security of the nation. But never mind.

Few people in the U.S. paid much attention to the no-Chinese law, but it’s at last taking deserved heat, thanks to a CNN interview with the three Chinese astronauts—or taikonauts—who flew China’s Shenzhou 10 mission in 2013. The network’s visit to China’s usually closed Space City, which will air on May 30, is a reporting coup, especially because of the entirely familiar, entirely un-scary world it reveals: serious taikonauts doing serious work with serious mission planners—every bit what you see behind the scenes at NASA or Russia’s Roscosmos.

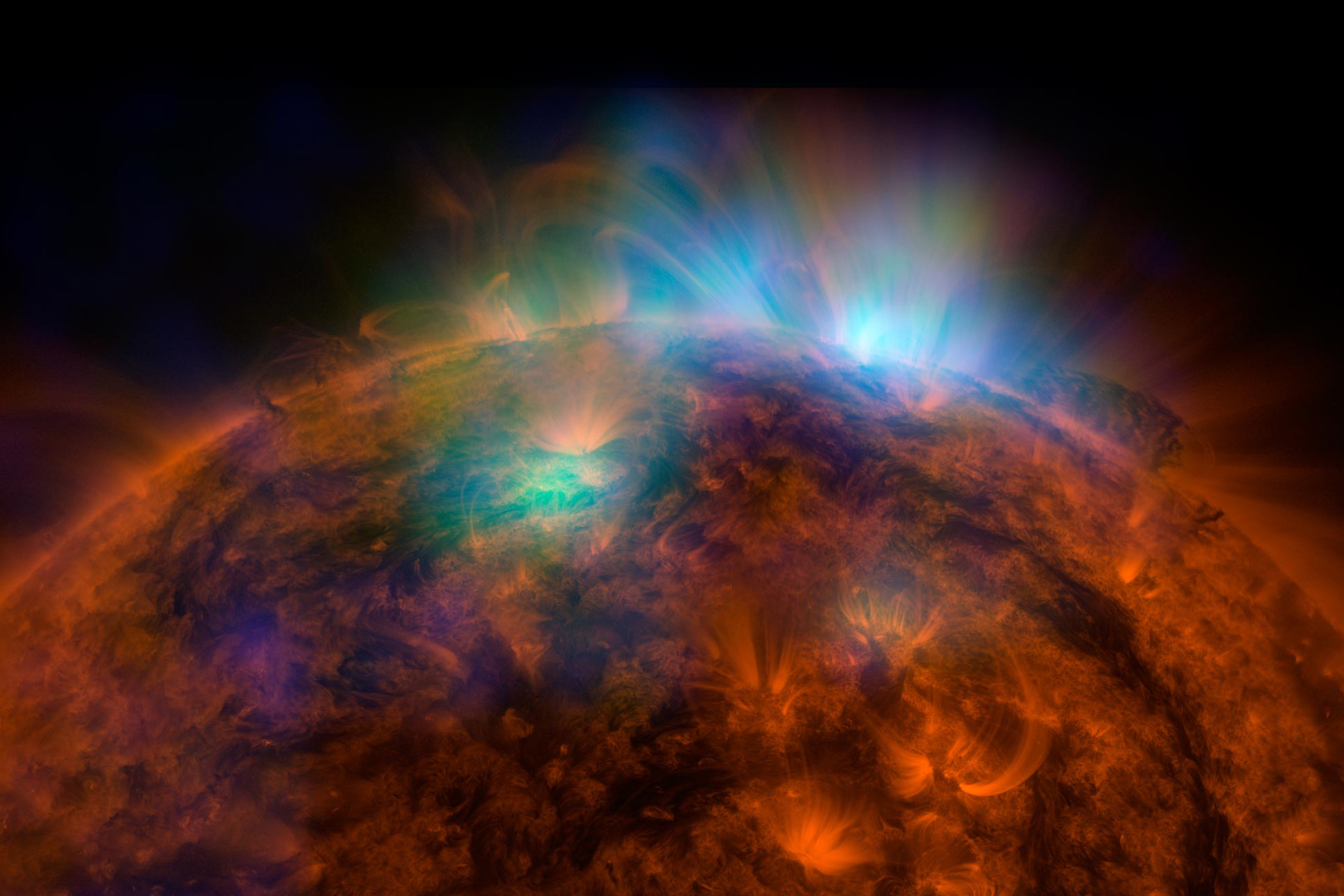

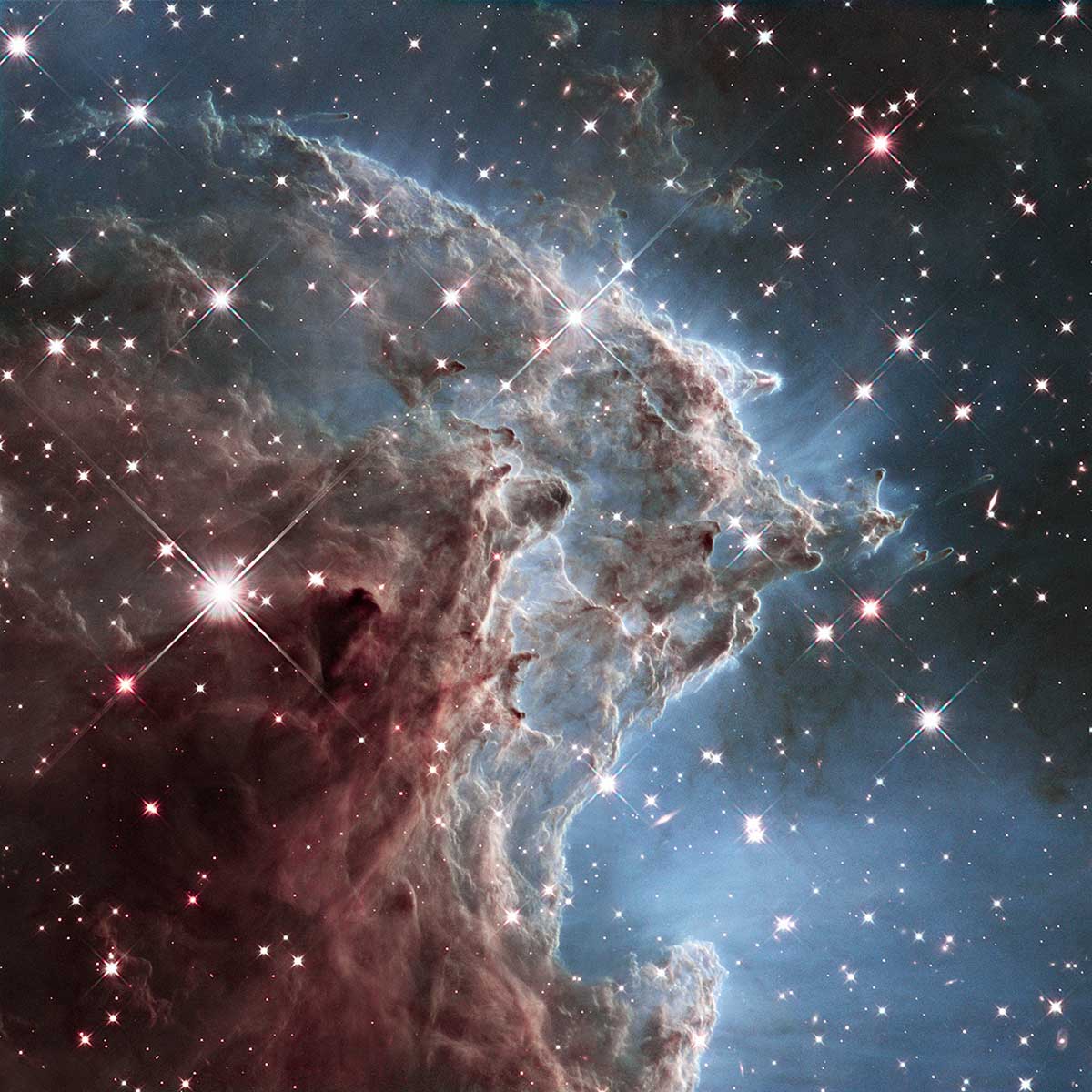

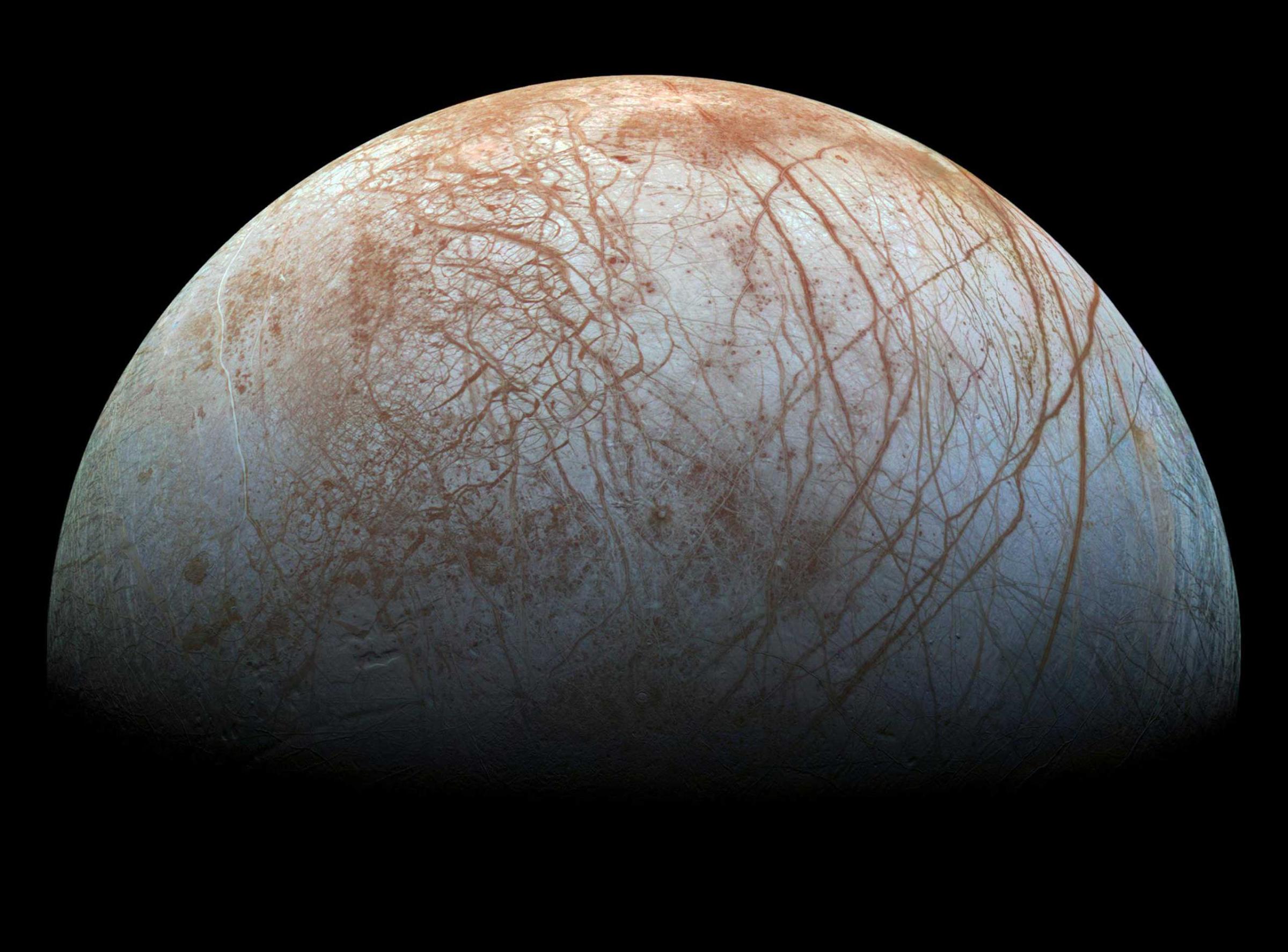

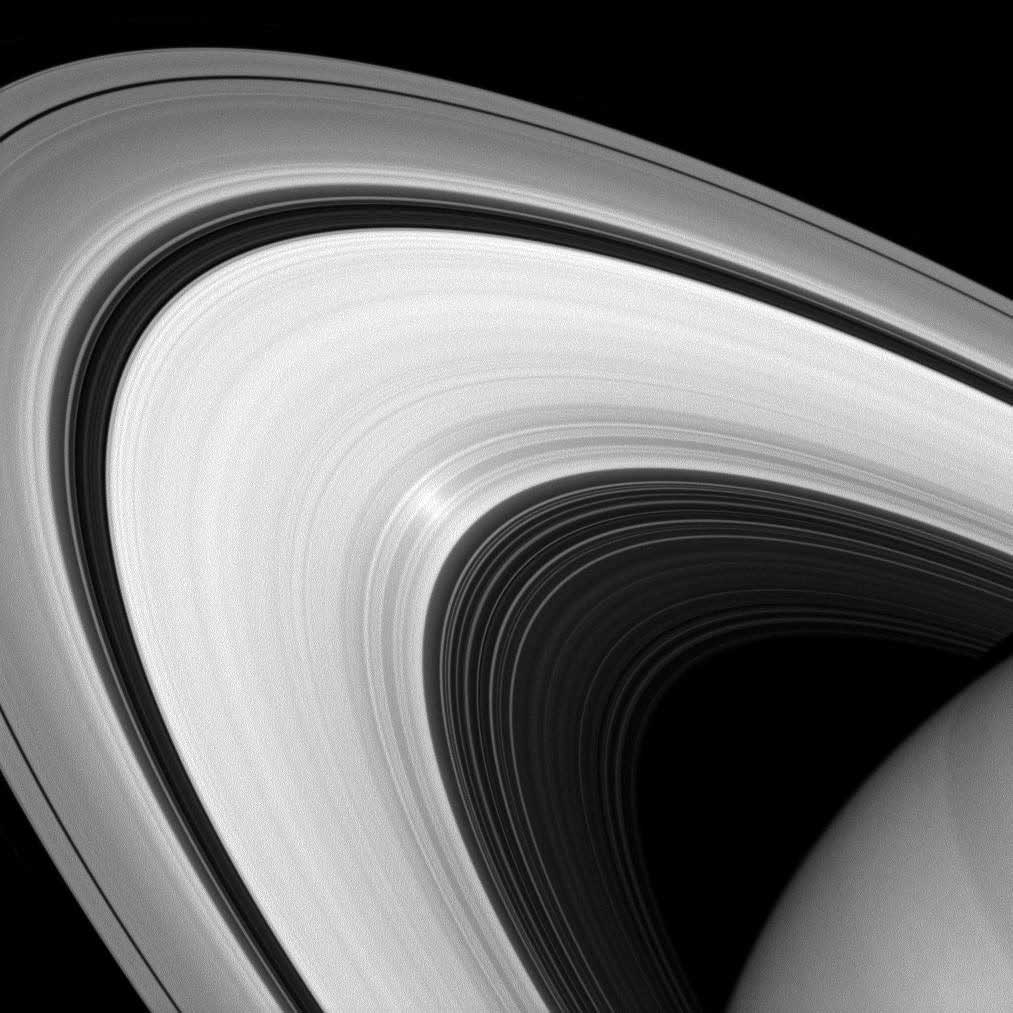

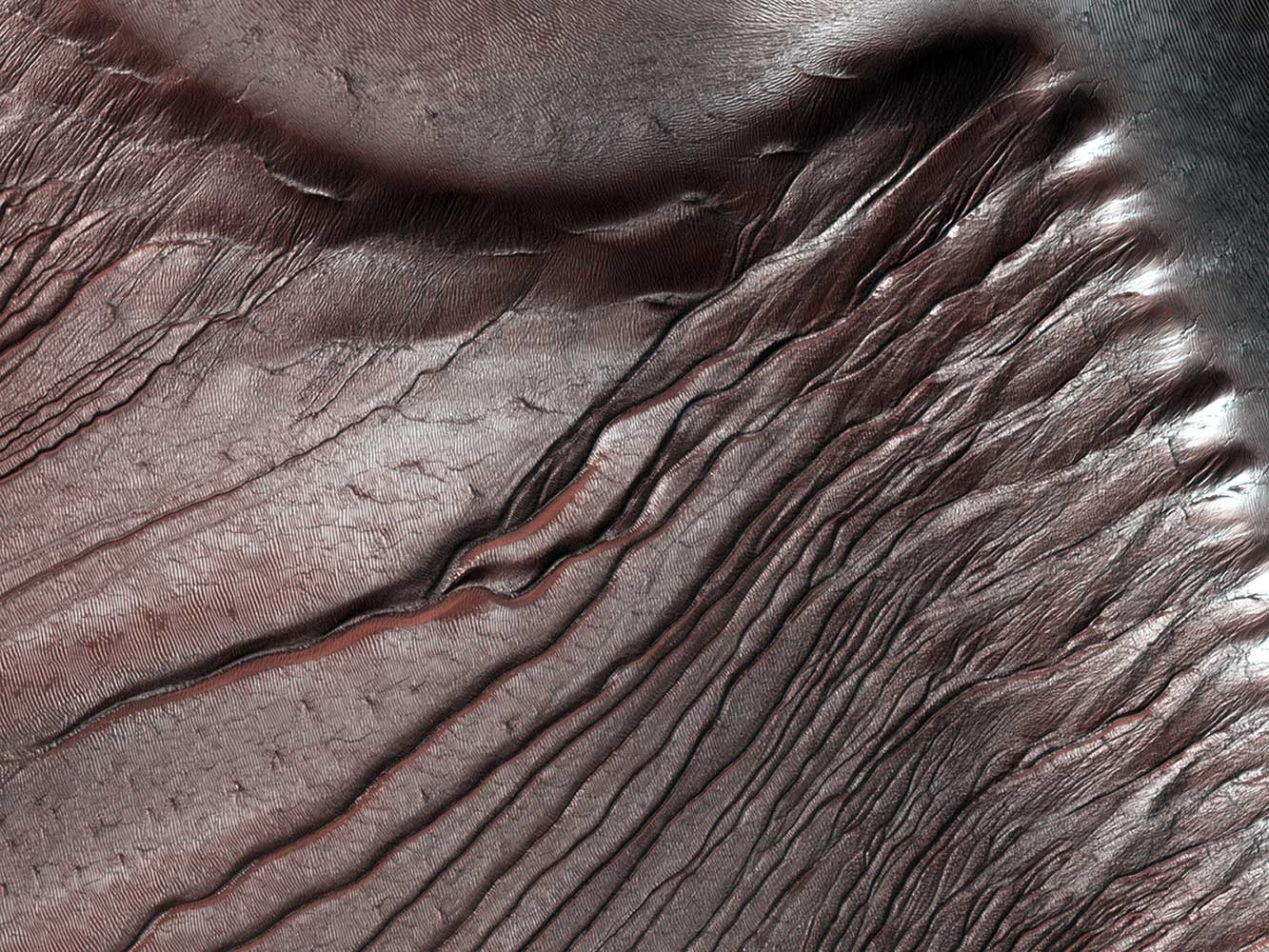

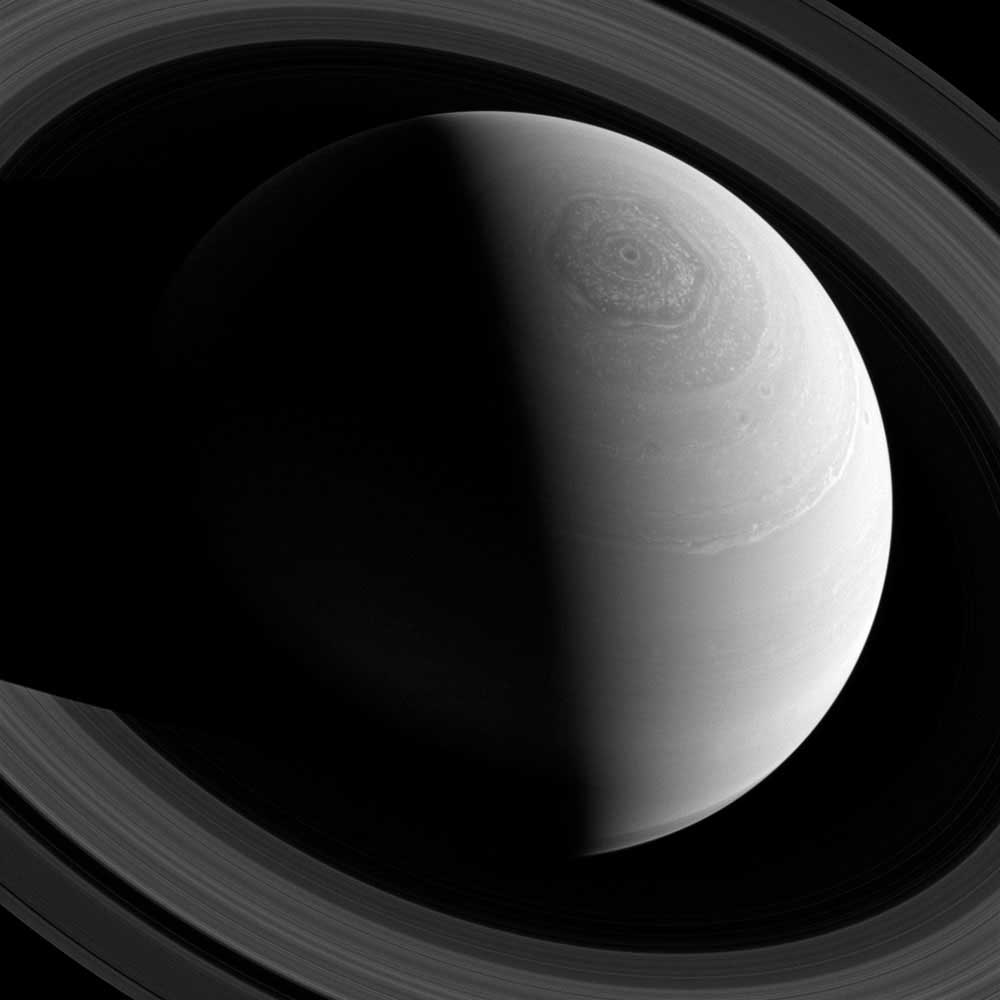

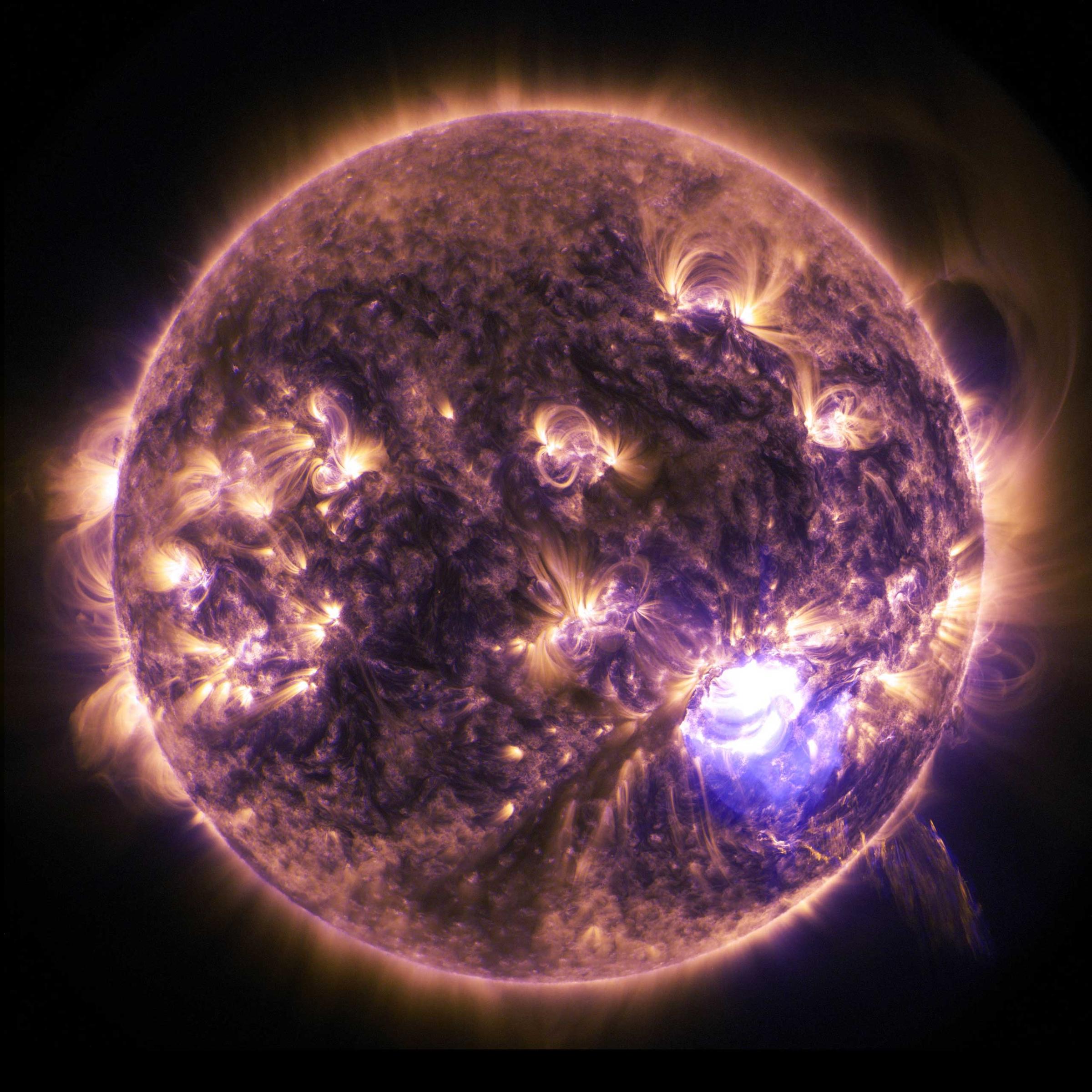

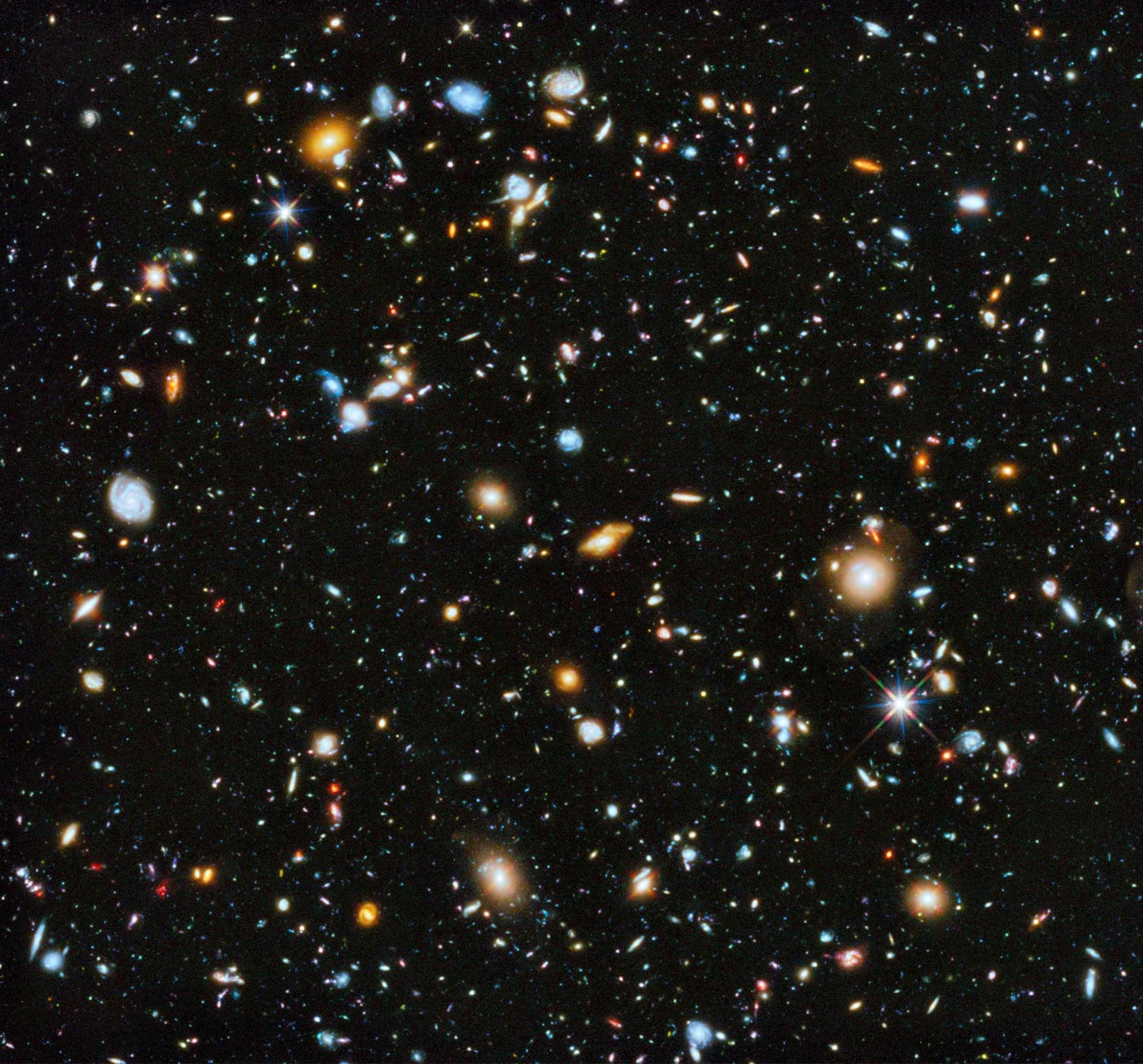

See the Most Beautiful Space Photos of 2014

And similar to the nature of those other space agencies too is the professed wish of the Chinese crews to work across national borders. “As an astronaut, I have a strong desire to fly with astronauts from other countries,” said Nie Haisheng, the Shenzhou 10 commander. “I also look forward to going to the International Space Station. Space is a family affair; many countries are developing their space programs and China, as a big country, should make our own contributions in this field.”

But that contribution can’t happen aboard the ISS. The 2011 law draws a sort of ex post facto justification from a study that was released in 2012 by the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, warning that China’s policymakers “view space power as one aspect of a broad international competition in comprehensive national strength and science and technology.” More darkly, there is the 2015 report prepared by the University of California, San Diego’s Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation, ominously titled “China Dream, Space Dream“, which concludes: “China’s efforts to use its space program to transform itself into a military, economic, and technological power may come at the expense of U.S. leadership and has serious implications for U.S. interests.”

OK, deep, cleansing breaths please. On the surface, the studies make a kind of nervous, reflexive sense. China is big, China is assertive, China has made clear its intentions to project its military power in ways it never has before—including to the high ground of space.

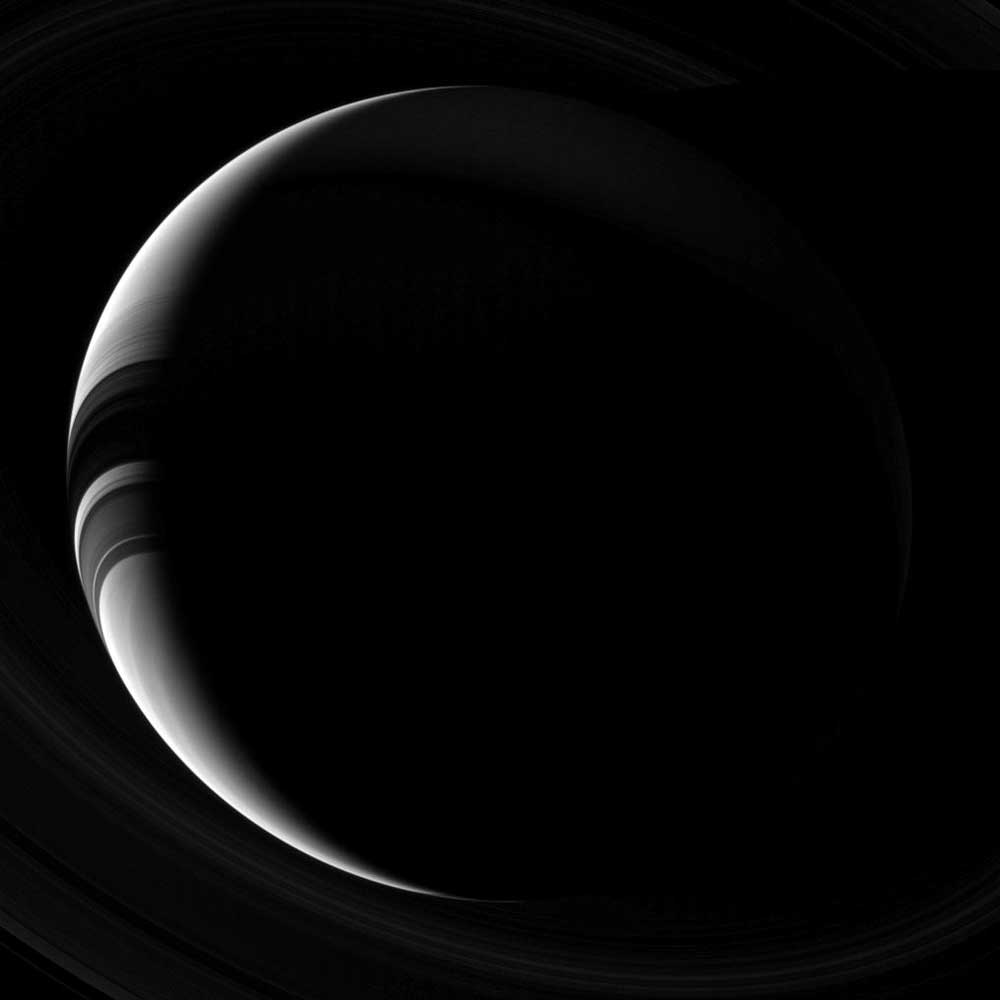

But if that sounds familiar it’s because it’s an echo of the Cold War hysteria that greeted the launch the Soviet Union’s Sputnik. The world’s first satellite, Sputnik was a terrifying, beach ball sized object that orbited the Earth from Oct. 1957 to January 1958, presenting the clear and present danger that at some point it might beep at us as it flew overhead. Every Soviet space feat that followed was one more log on the Cold War fire, one more reason to conclude that we were in a mortal arms and technology race and woe betide us if the guys on the other side got so much as a peek at what we were doing.

That argument failed for a lot of reasons. For one thing, the Soviets hardly needed a peek at our tech since they were the ones who were winning. When you’re in first place in your division you don’t to steal ideas from the guys in last. Something similar is true of the Chinese now.

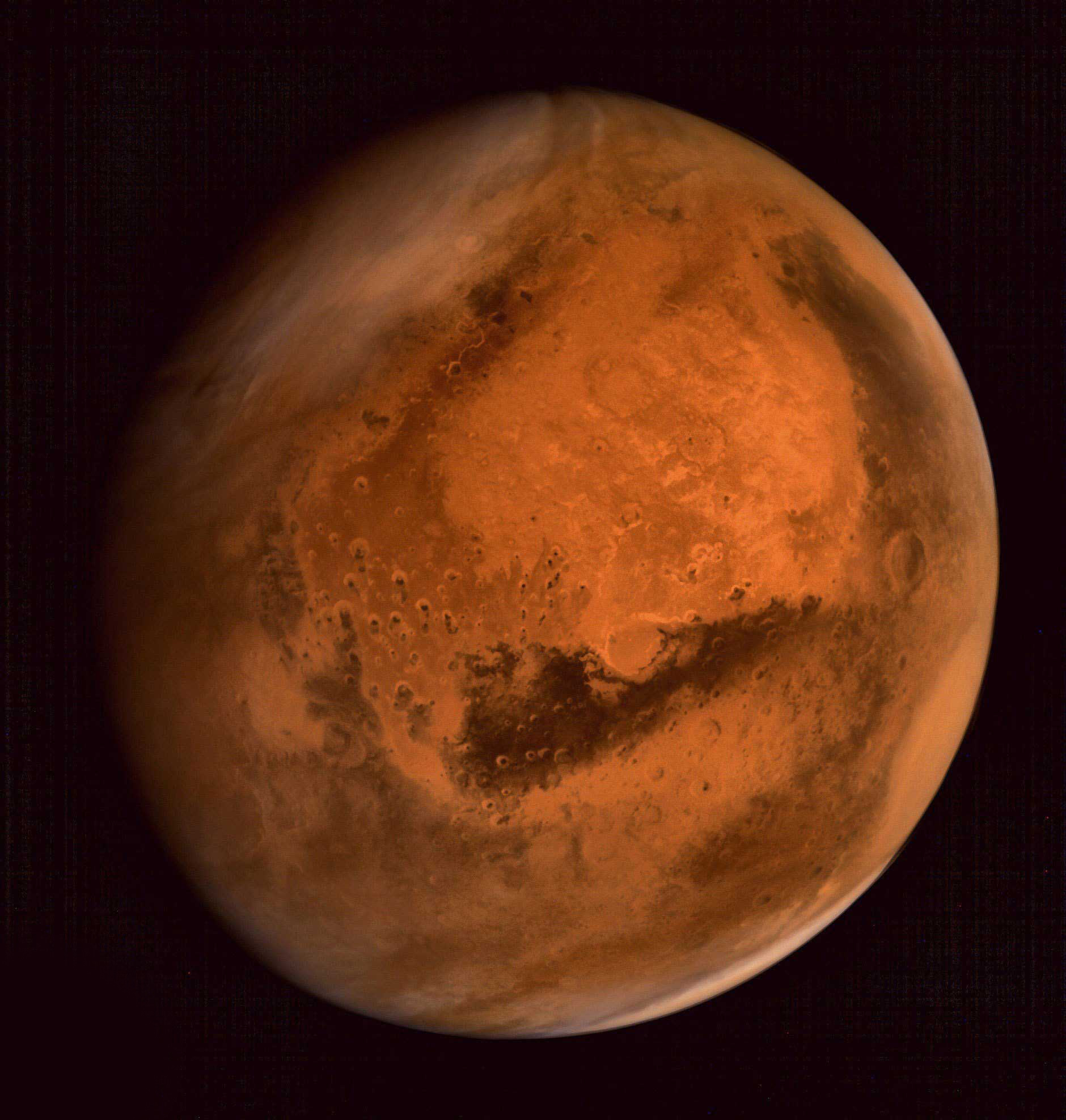

After launching their first solo astronaut in 2003, they have followed in rapid succession with two-person and then three-person crews, and have mastered both spacewalking and orbital docking. They have orbited a core module for their own eventual space station, have sent multiple spacecraft to the moon and are planning a Mars rover. They didn’t do all that by filching American tech.

The doubters are unappeased, however. Both these reports warn that all of China’s technological know-how, no matter how they acquired it, has multiple uses, and can be put to either good or nefarious ends, a fact that is pretty much true of every, single technological innovation from fire through the Apple Watch.

Even if all of the fears were well-founded—even if a Chinese Death Star were under construction at this moment in a mountain lair in Xinjiang—forbidding the kind of international handshaking and cooperating that is made possible by a facility like the ISS is precisely the wrong way to to go about reducing the threat. The joint Apollo-Soyuz mission in 1975 achieved little of technological significance, but it was part of a broader thaw between Moscow and Washington. That mattered, in the same way ping pong diplomacy between the U.S. and China in 1971 was about nothing more than a game—until it was suddenly about much more.

Well before the ISS was built and occupied, the shuttle was already flying American crews to Russia’s Mir space station. Russia later became America’s leading partner in operating and building the ISS—a shrewd American move that both offloaded some of the cost of the station and provided work for Russian missile engineers who found themselves idle after the Berlin Wall fell and could easily have sold their services to nuclear nasties like North Korea or Iran.

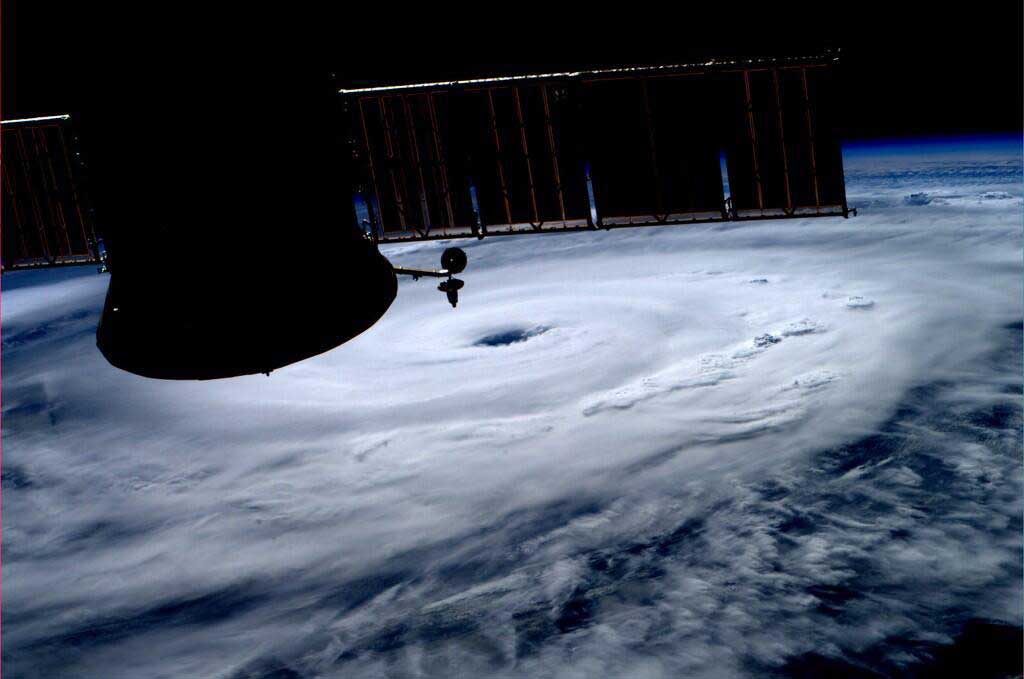

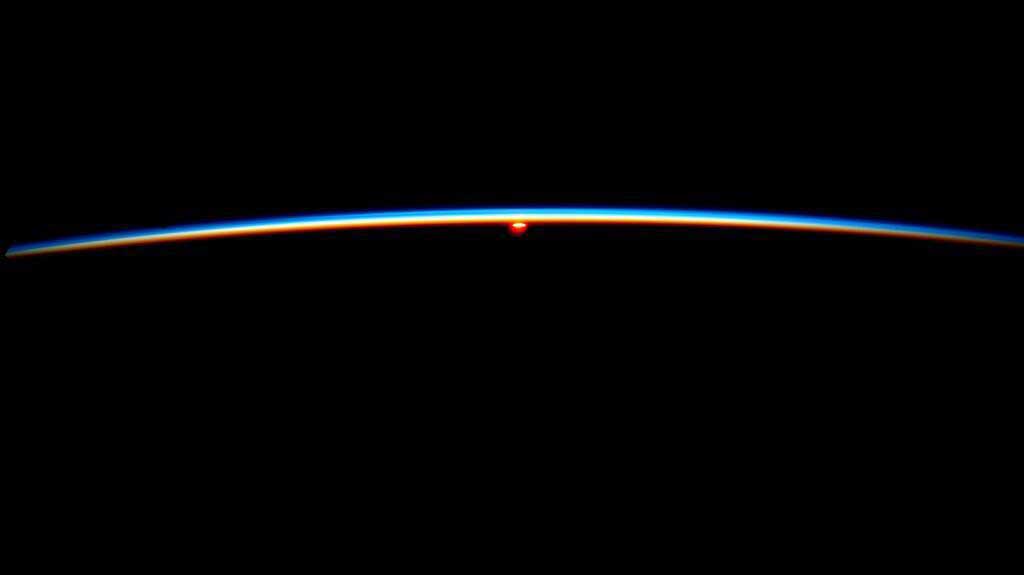

The technology aboard the ISS is not the kind that a Chinese astronaut with ill will would want to or need to steal. And more to the point, if there’s one thing the men and women who fly in space will tell you, it’s that once they get there, terrestrial politics mean nothing at all—the sandbox silliness of politicians who are not relying on the cooperation of a few close crewmates to keep them alive and safe as they race through low Earth orbit. From space, as astronauts like to say, you can’t see borders. It’s a perspective the lawmakers in Washington could use.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com