Mice certainly aren’t men, but they can teach us a lot about memories. And in the latest experiments, mice are helping to resolve a long-simmering debate about what happens to “lost” memories. Are they wiped out permanently, or are they still there, but just somehow out of reach?

Researchers in the lab of Susumu Tonegawa at the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT conducted a series of studies using the latest light-based brain tracking techniques to show that memories in certain forms of amnesia aren’t erased, but remain intact and potentially retrievable. Their findings, published Thursday in the journal Science, are based on experiments in mice, but they could have real implications for humans, too.

MORE: How to Improve Your Memory Skills

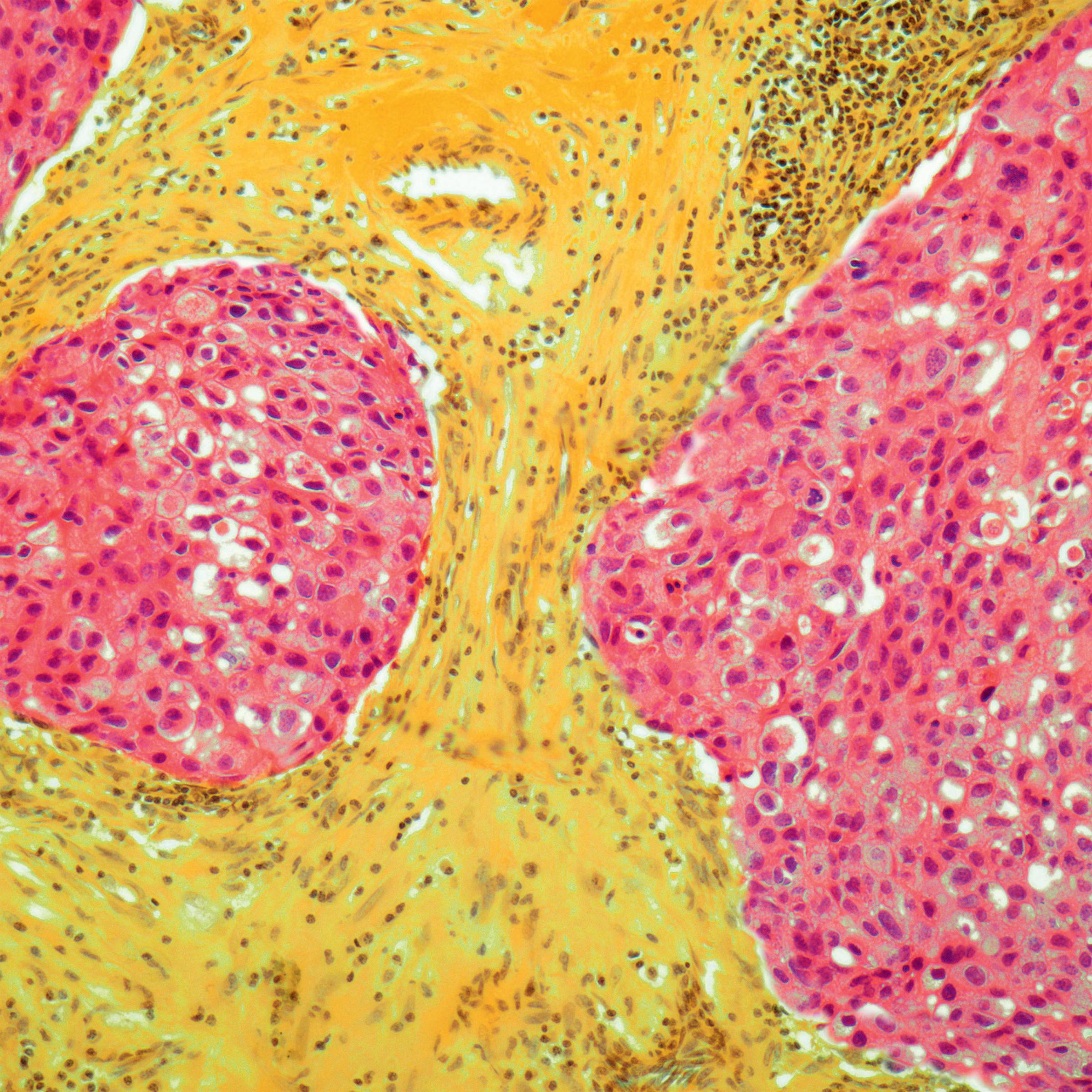

The mice were trained to remember getting a shock in a certain chamber. The scientists then used protein labels to tag the specific cells in the hippocampus of the brain that were activated and responsible for making that memory. According to Tomas Ryan, lead author of the paper, anywhere from 3% to 5% of the cells in a portion of the hippocampus are recruited to form a memory. When these mice were then placed into the same room again, they froze, recalling and anticipating the shock. But when the animals were given a drug that interrupts the memory-making process immediately after the shock, they no longer remembered the shock and didn’t freeze if placed in the room.

Then the researchers tried to retrieve the lost memory by simply activating just the circuit of cells that were responsible for the memory — without the shock. They did this using a technique called optogenetics, in which laser lights stimulate the tagged cells in the hippocampus. When the circuit was activated, the animals froze again, even if they were in a neutral room that they didn’t associate with the shock. The results suggest, says Ryan, that “this type of amnesia in general is due to inaccessibility of a memory; the memory itself is still present.”

MORE: You Asked: Do Brain Games Really Improve Memory?

While the studies were done in mice, the findings could have implications for memory loss in humans. Specifically, the work suggests that memories lost after a traumatic brain injury such as a concussion, car accident or even a stressful event or some forms of dementia may be retrievable. How successful that may be depends on how soon after the memory-robbing event the recall occurs; it’s more likely to happen, says Ryan, soon after the traumatic event and before the memory is completely stored in the brain. But if the brain is severely damaged, then it’s possible that the process of storing the memory itself is compromised, and the memory won’t be retrievable.

Still, there may be conditions where being able to find lost memories is critical, and these results indicate that those memories are still there, it’s a just a matter of finding the best way to retrieve them, which hasn’t been worked out yet for people.

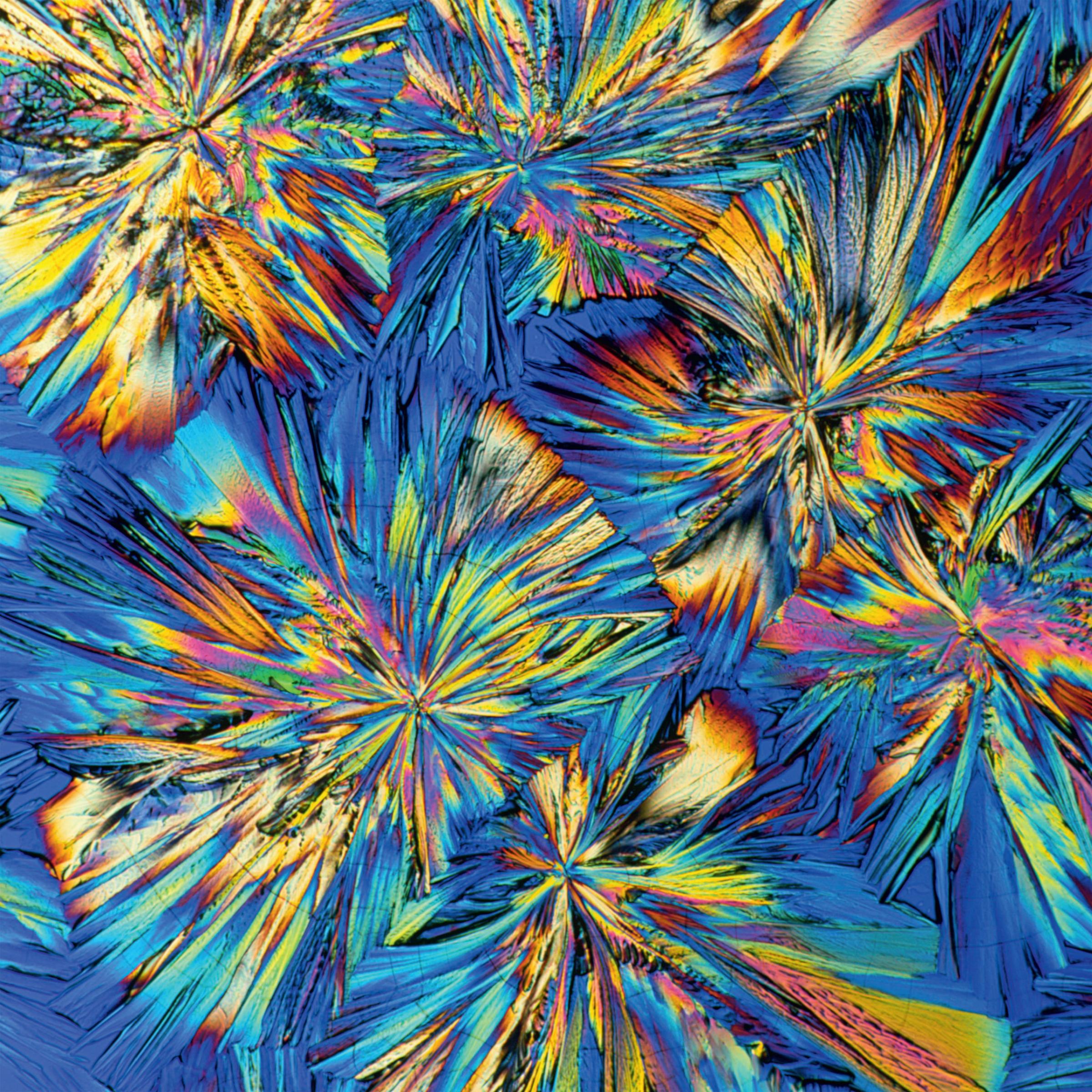

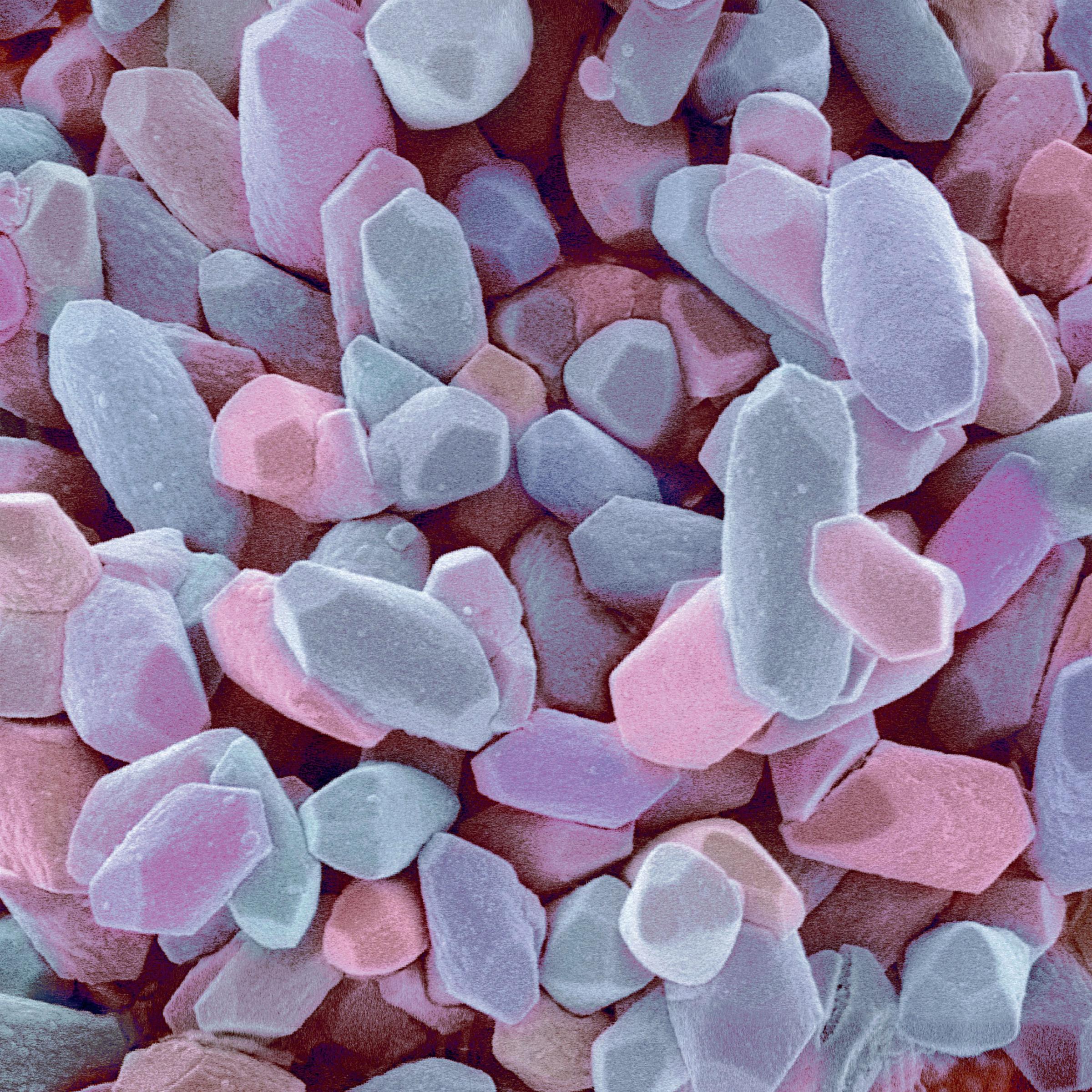

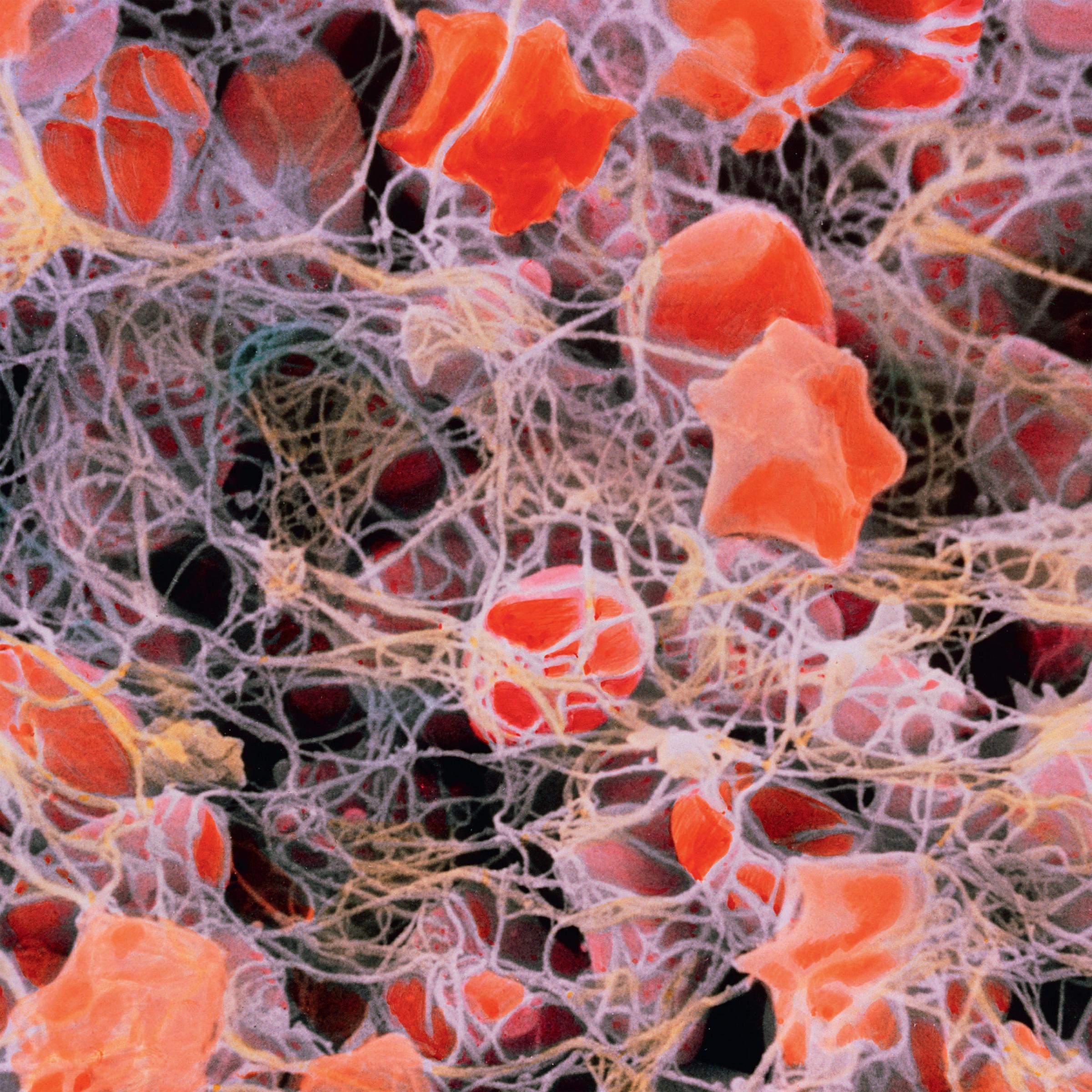

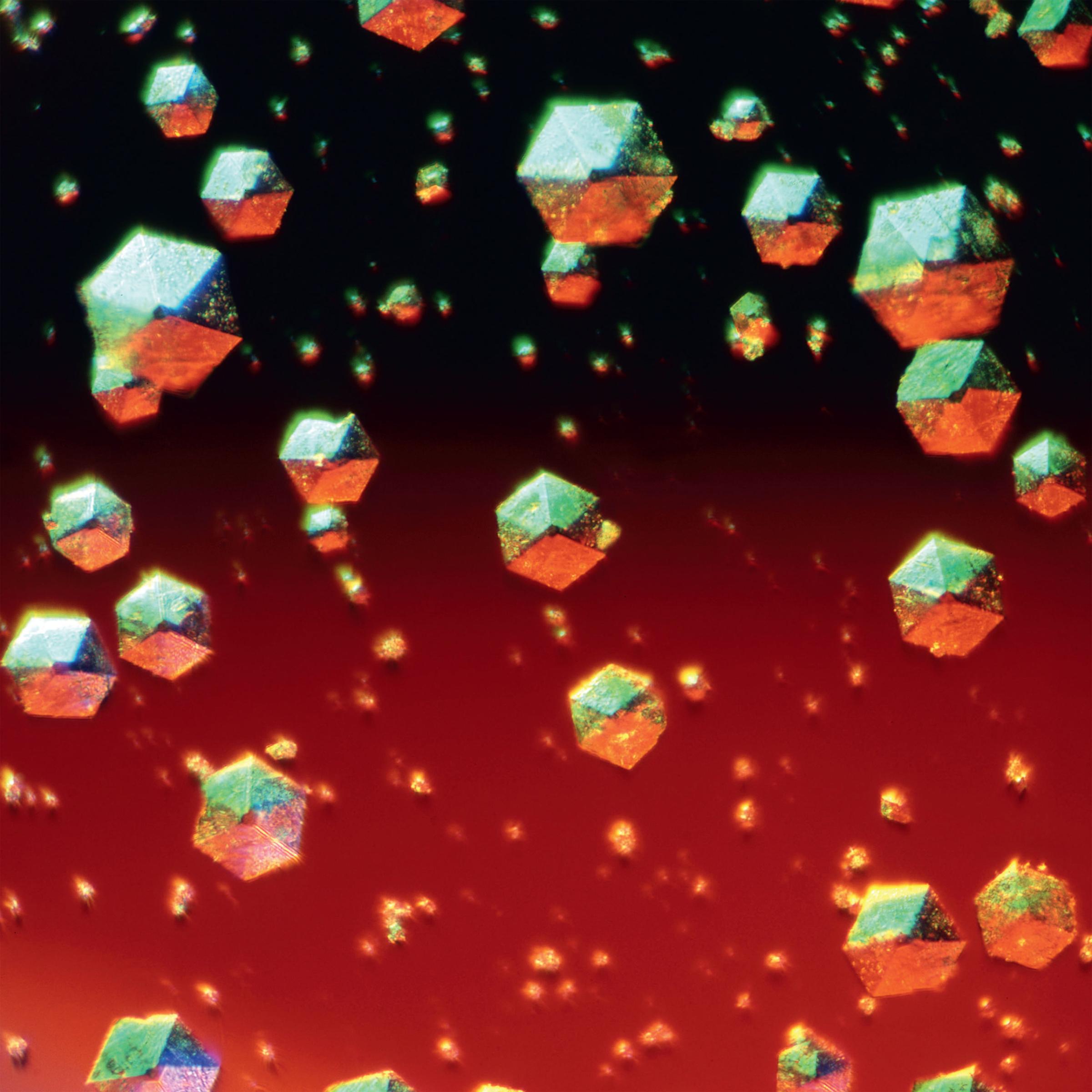

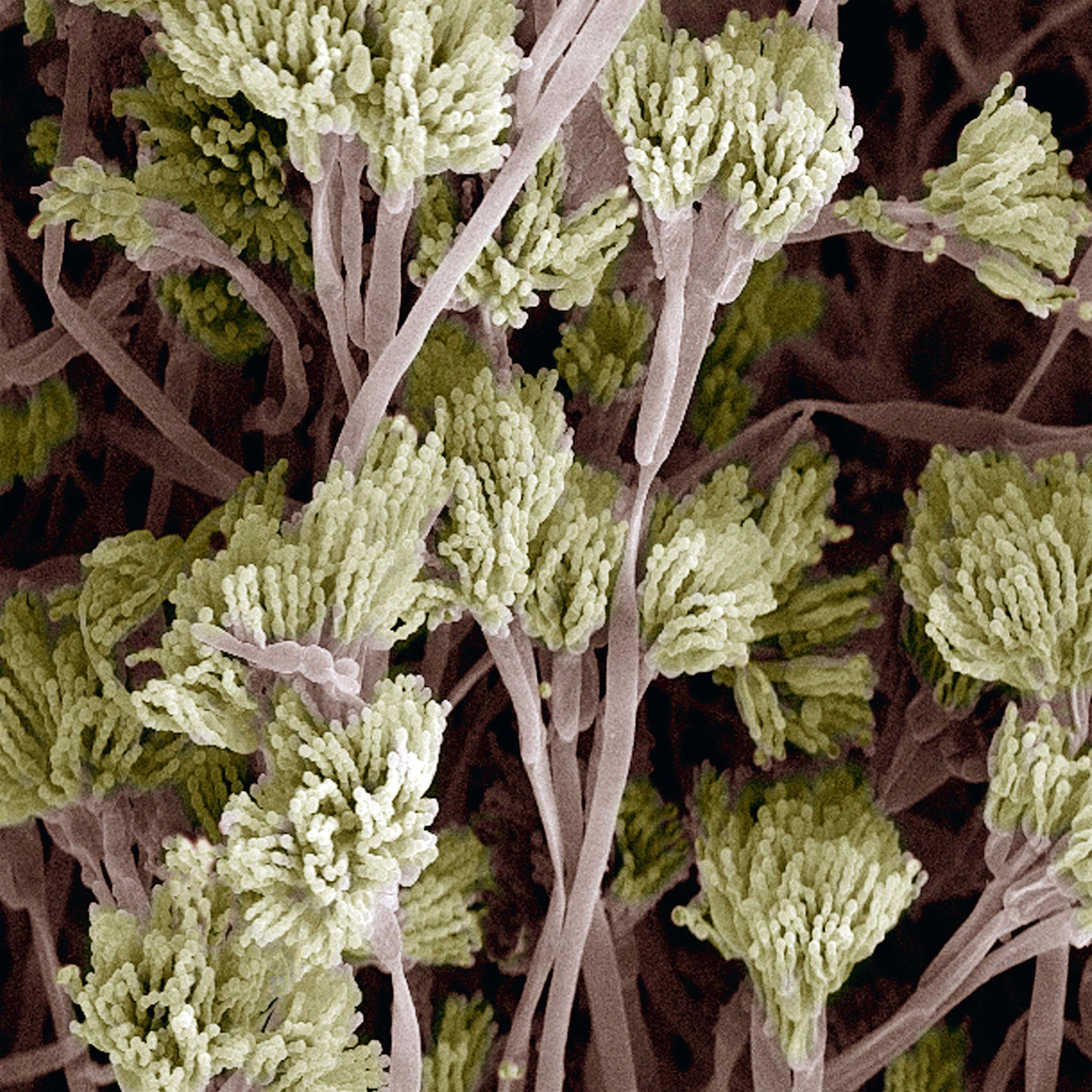

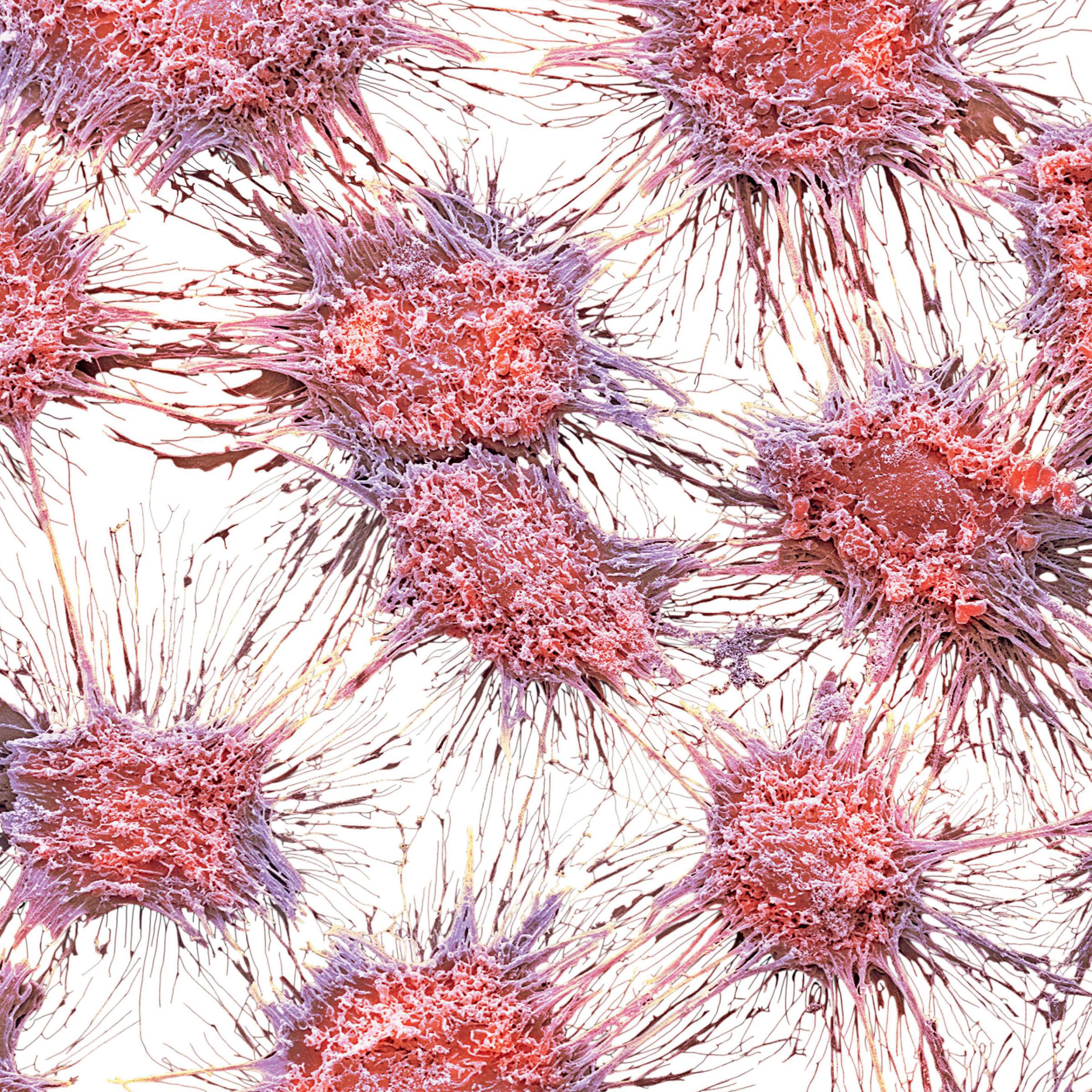

See the Human Body Under a Microscope

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com