Correction appended, May 27

Rick Santorum was closing out his speech to the GOP’s governing class at a posh desert resort near Phoenix. His time to address the Republican National Committee coming to a close, he took a moment to remind the party’s elders of their history. “We stick with tradition,” the former Senator from Pennsylvania said in early May.

With restless party chairmen and activists shifting in their seats, the failed 2012 candidate made a not-so-subtle pitch for the Santorum for President, 2016 Edition, which started on Wednesday, with a rally in Cabot, Pa.

“Since primaries and caucuses went into effect, every Republican nominee has met one of three tests,” Santorum said in Arizona. “One, they were Vice President. Two, they were the son of a former President. And three, they came in second place the last time and ran again and won.”

If history were predictive of how Republicans pick their nominee, then 2016’s nomination should be Santorum’s for the taking. He came in second to Romney in 2012 and, in his telling, won as many nominating contests as Reagan did during his 1976 bid. (In truth, Reagan won 11 primaries in 23 states, whereas Santorum won a combined 11 contests in states that held primaries and caucuses.)

But history alone is not going to overcome Santorum’s significant obstacles as he seeks the White House for a second time. With a penchant for incendiary language, a stronger crop of likely competitors, an expected nine-figure deficit against his rivals for the nod, few of his competitors now count him in the top tier of candidates, and there are serious questions about him even making the cut for the first debate on Aug. 6.

“I know what it’s like to be an underdog,” Santorum said in Pennsylvania’s Butler County on Wednesday, beginning an uphill climb for the nomination. “Four years ago, well, no one gave us much of a chance. But we won 11 states. We got 4 million votes. And it’s not just because I stood for something. It’s because I stood for someone: the American worker.”

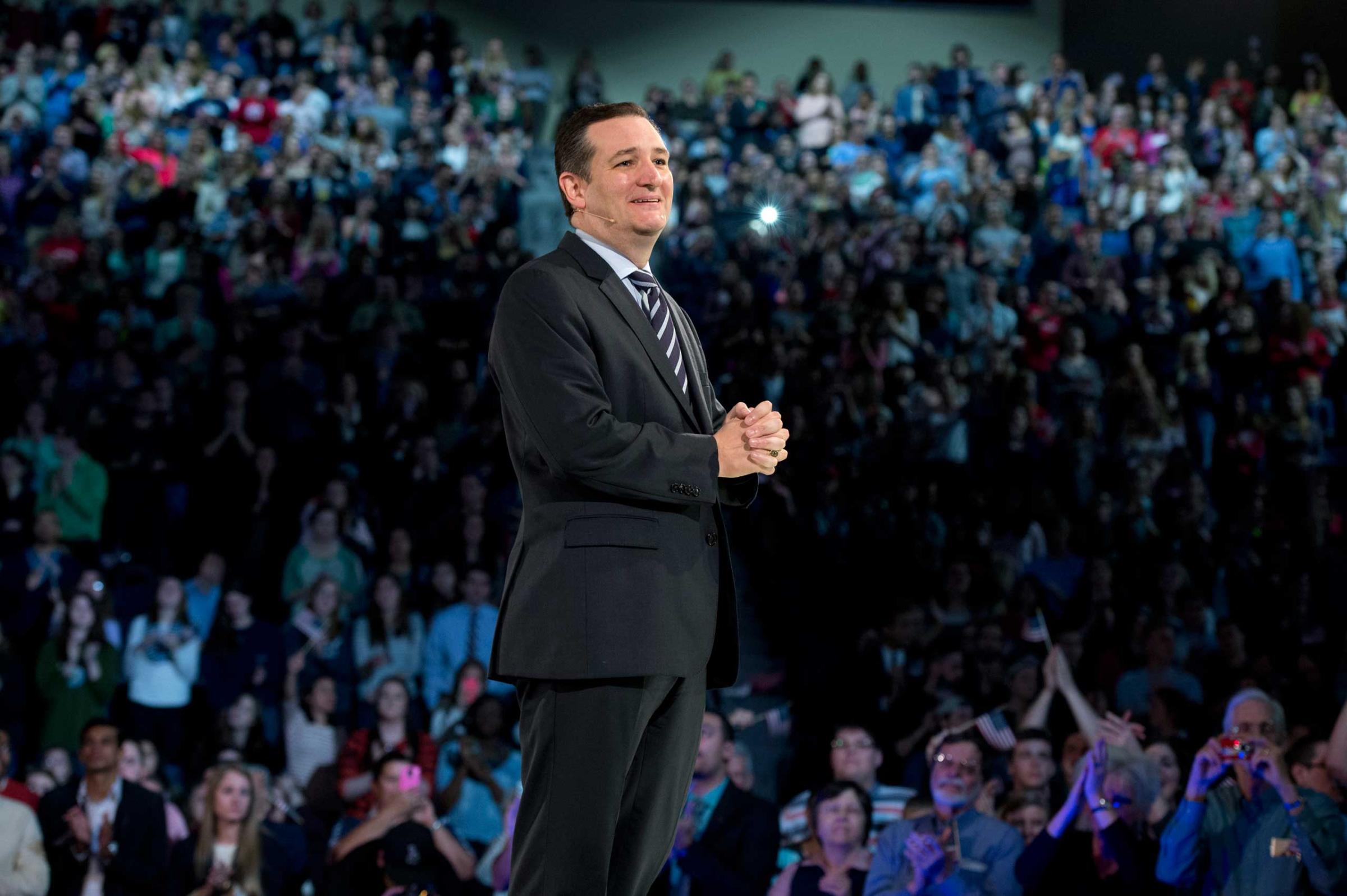

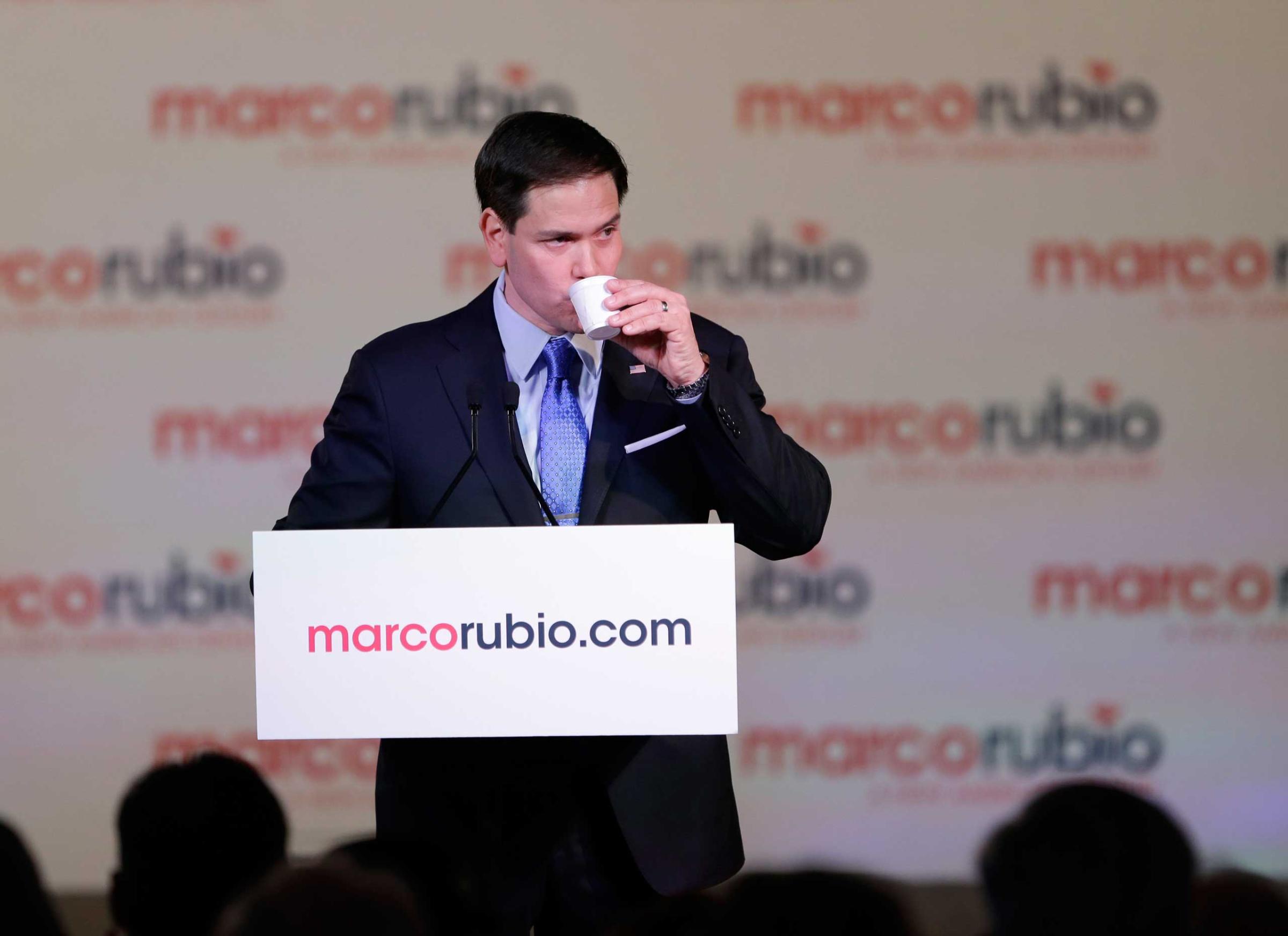

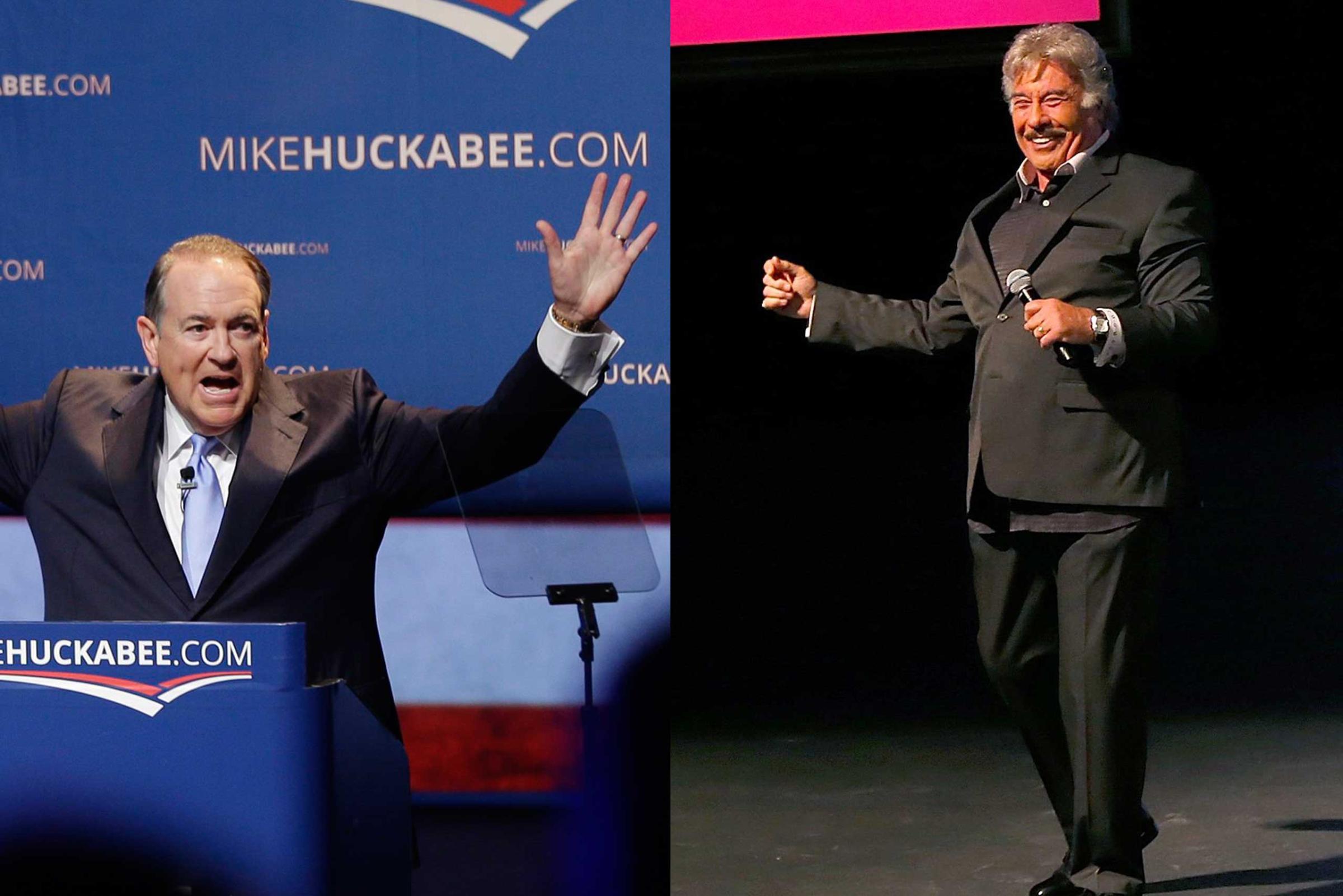

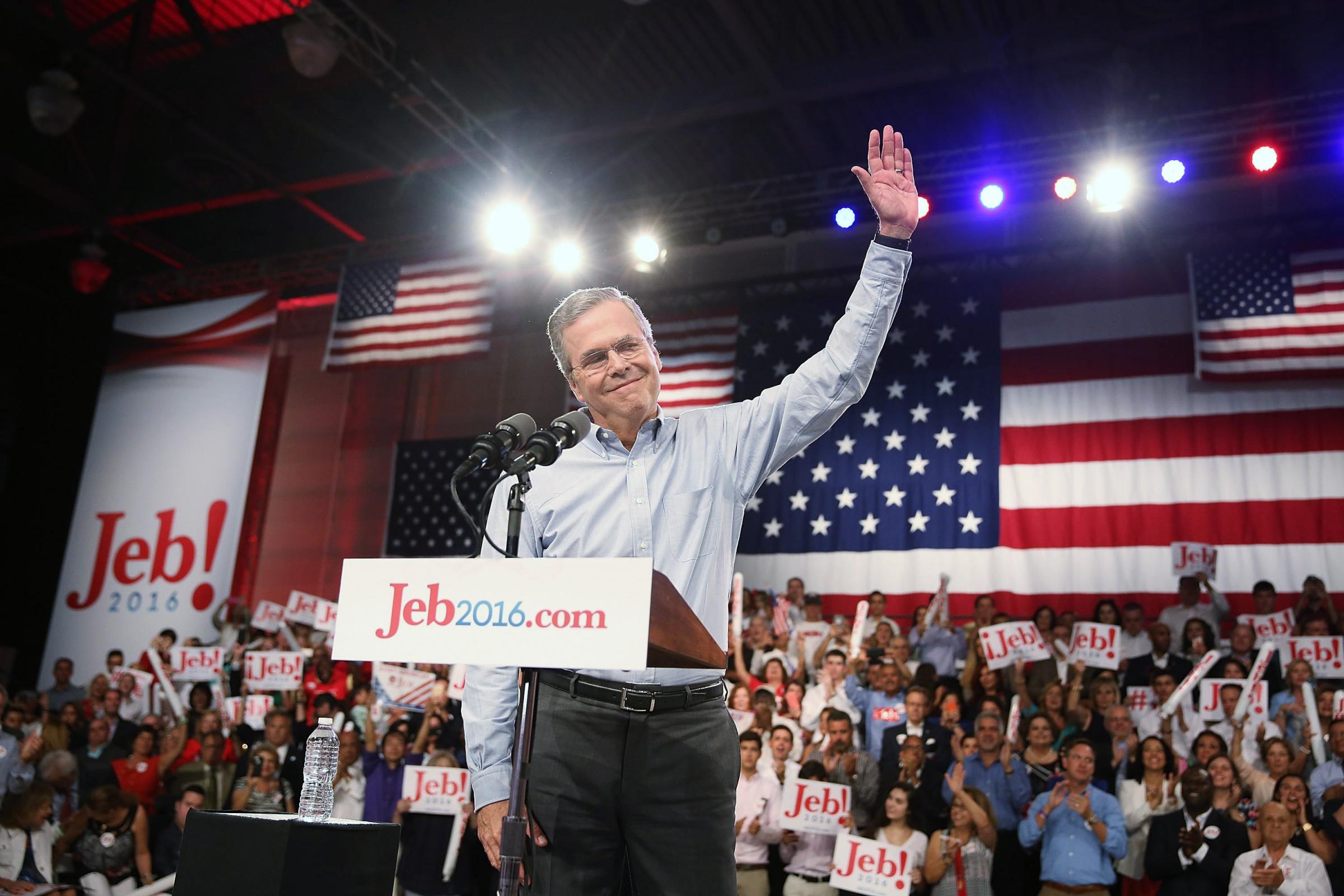

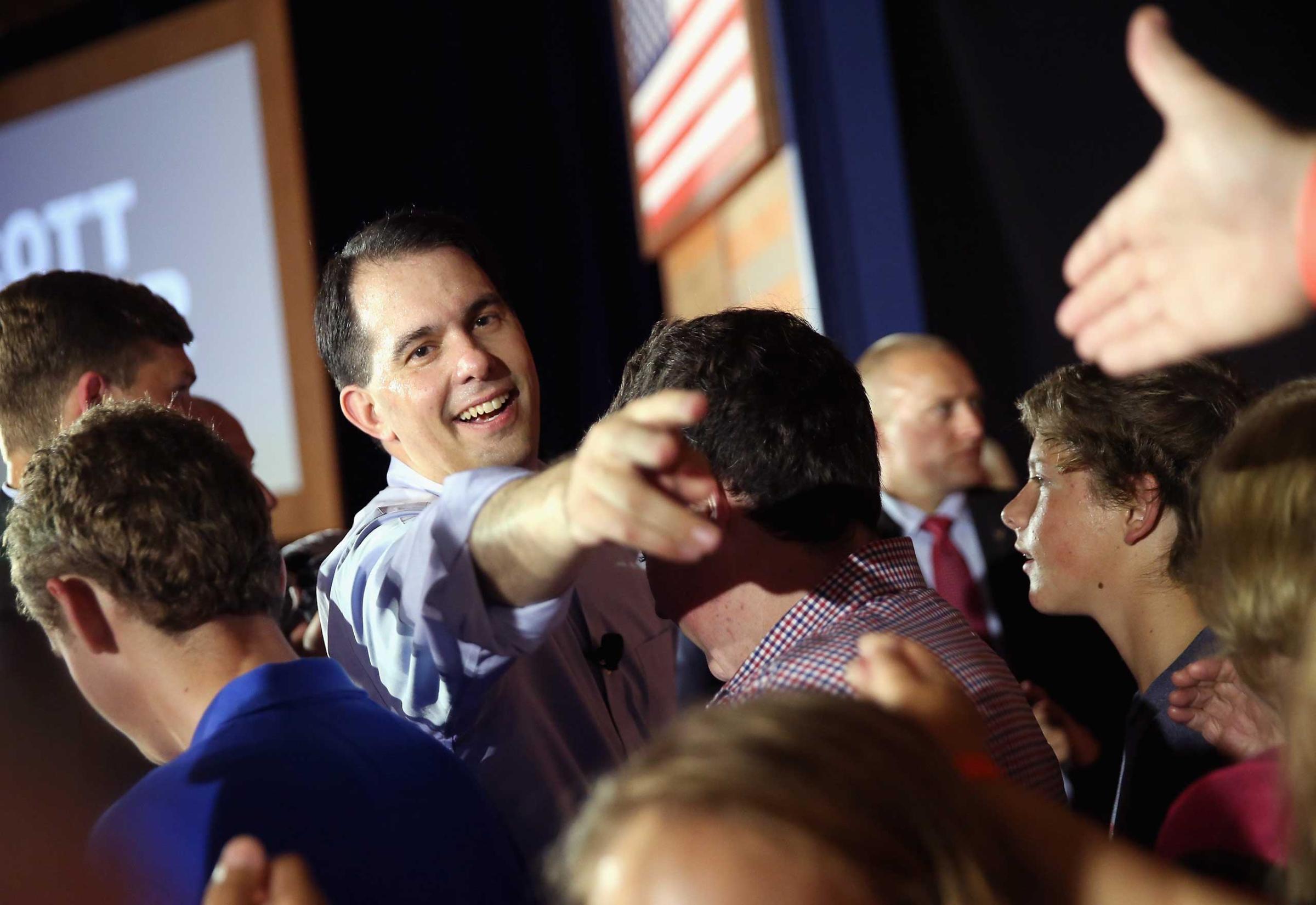

But this time, Santorum faces a tougher field of competitors. Fresh-faced newcomers, such as Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida and Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky, have the GOP optimistic it can appeal beyond its shrinking footprint. Conservative rock stars such as Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker and Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas can electrify crowds. Former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee can tap into his past as a Baptist pastor and whip the Christian conservative base of the party into a frenzy. And former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush has the pedigree and roster of campaign donors that might overshadow missing other traits voters say they are seeking.

Santorum, out of office since early 2007 after losing reelection by 18 percentage points, can do none of those. He is 57—a decade older than some of his rivals and roughly in the middle of the pack when it comes to birthdays. He fails to energize conservative audiences with speeches that are closer to college lectures than political rallying cries. He speaks about his faith in deeply personal ways but cannot match Huckabee in the pulpit. And Santorum is an admittedly terrible fundraiser, often turning off would-be donors with his contrarian style.

“The last race, we changed the debate,” Santorum told his kick-off rally. “This race, with your help and God’s grace, we can change this nation. Join us.”

His crowds so far this year have been thin. But Santorum is used to that. He toiled in relative obscurity in 2011, visiting all 99 Iowa counties in the passenger seat of an activist’s pickup. He staged a surprise win in the leadoff caucuses but had insufficient infrastructure to capitalize on Iowa’s enthusiasm.

Instead, he turned to often divisive and cantankerous rhetoric. For instance, Santorum could seldom open his mouth with unleashing an invective about others and cast himself as a victim. He called Romney “the worst Republican in the country to put up against Barack Obama.” He said John F. Kennedy’s 1960 speech, in which the future president said “the separation of church and state is absolute,” made the Pennsylvania Senator “want to throw up.” Santorum promised that, as President, he would talk about “the dangers of contraception in this country, the whole sexual libertine idea.”

Earlier this year, Santorum told NBC News that his 2012 campaign was defined by “dumb things” he said and “crazy stuff that doesn’t have anything to do with anything.” He acknowledges things went off the rails the further into the nominating process he hobbled, even as his campaign was running out of cash and the White House nod grew increasingly impossible to snag.

Even so, Santorum crowed to a tea party crowd in South Carolina earlier this year: “I was the last person standing.” He earned 234 pledged delegates to the party’s nominating convention in Tampa. Romney had amassed more than 1,400.

Even so, Santorum tells voters and reporters his political endurance qualifies him to become the nominee this time. He insists he is battle-tested under pressure, unlike his rivals.

“As you’ve seen, Commander in Chief is not an entry-level position, and the White House is the last place for on-the-job training,” Santorum said Wednesday.

Santorum has his history right. Mitt Romney was rewarded the nomination in 2012 after failing to win it in 2008. John McCain’s 2000 failed run was rewarded with the nomination in 2008. Bob Dole won the nomination in 1992 after an unsuccessful turn as the GOP’s 1976 Vice Presidential nominee. George H.W. Bush was the nominee in 1988 after losing to Ronald Reagan in the 1980 primaries and then serving eight years as his Vice President. Reagan himself won the 1980 nomination after failing to win the nod in 1976. Richard Nixon won the White House in 1968; he served eight years as Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Vice President before losing the Presidency as the GOP nominee in 1960.

Only four times in the last 60 years has the Republican electorate nominated a Presidential neophyte—and the most recent examples are suspect at best. George W. Bush, the son of a President, won the White House in 2000 as a first-time national candidate. Gerald Ford rose to the Presidency after Nixon’s resignation and lost the White House in 1976 to Democrat Jimmy Carter as a first-time coast-to-coast candidate. Barry Goldwater came up short as the GOP nominee in 1964, and Eisenhower won the 1952 nomination and Presidency as a first-time political candidate.

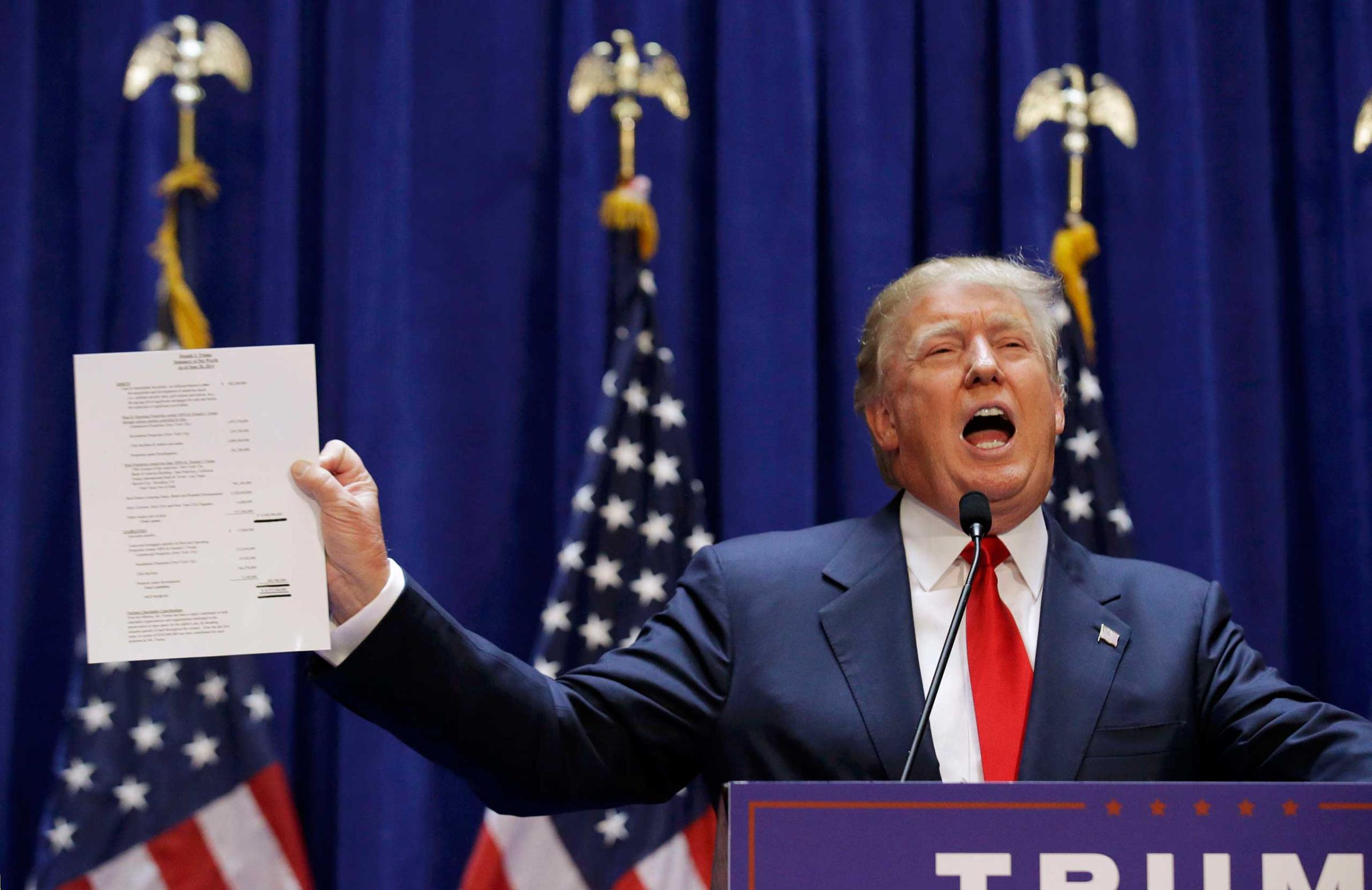

But those figures—new and veteran—ran sophisticated campaigns and had not alienated great swaths of the GOP. Santorum’s situation looks different, with several of his former top advisers having defected for other campaigns: 2012 campaign manager Mike Biundo is a Paul senior adviser. Spokespeople Hogan Gidley and Alice Stewart have signed with Huckabee. Even Santorum’s erstwhile driver from 2012, Chuck Laudner, has abandoned him—for Donald Trump.

Correction: The original version of this story misstated the date of the first Republican presidential debate. It is Aug. 6.

See the 2016 Candidates' Campaign Launches

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com