In the annals of consumer electronics companies that have slipped from great heights, none has taken a bigger fall far from its glory days than Sony. But after years of struggling to right itself, the company is finally making real progress on a turnaround.

Just as Apple helped revive itself in the early 2000s with the iPod, Sony built much of its success on the idea of helping people carry music around in their pocket–first with the transistor radio in the 50s and 60s and later with the Walkman portable cassette player. Those products, coupled with smart engineering, made the Sony brand synonymous with peerless quality.

In the early 2000s, Sony began to lose its competitive edge. Rivals like Samsung had emerged to undercut its higher-priced TVs and stereos. Sony couldn’t get a foothold in new markets like mp3 players. Its earlier expansion into new areas like insurance and its overspending on film and music studios left it with a structure that was at once bloated and siloed.

Sony named Howard Stringer as CEO in 2005 to turn things around. Stringer cut a charismatic figure, but couldn’t speak Japanese and, as a lifelong media executive, lacked an engineering background. Stringer tried to conjure a convergence of electronics and media properties that never quite gelled. (Stringer is on the board of Time Inc.) Meanwhile, further setbacks struck: the global recession in 2009, the Fukushima earthquake in 2011 and a stronger yen that hurt Japanese exports.

MORE: How Apple Just Save Best Buy

Sony has posted net losses for six of the past seven years. As a result, the price of its ADRs traded on the NYSE fell from $55 in early 2008 to below $10 in late 2012. (An ADR is a stock that trades in the U.S. but represents a specific number of shares in a foreign corporation.) Its credit ratings eventually fell to near junk levels. But then things began to look up: After bottoming out below $10 in 2012, its ADRs have risen back near $33 this month, a rally of 238% in the last two and a half years.

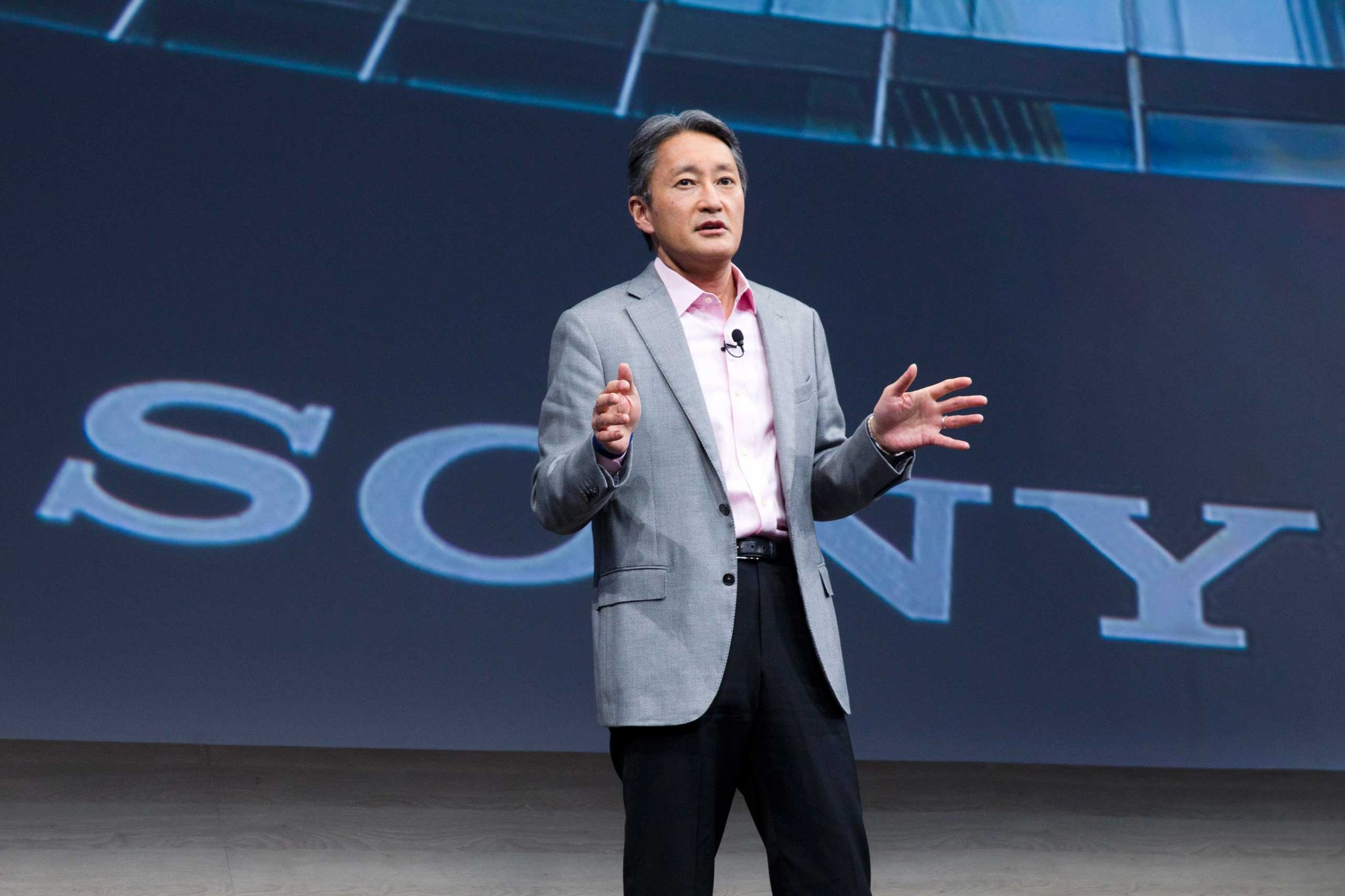

The change came after Sony replaced Stringer with Kazuo Hirai in early 2012. Hirai was a Sony veteran known for wringing profits from troubled businesses like the PlayStation gaming division. And like Stringer, Hirai didn’t fit the mold of the Japanese salaryman. Hirai grew up in Japan and North America, giving him a fluency in English and also a gift for being plainspoken, like when he told the Wall Street Journal on taking the job, “It’s one issue after another. I feel like, “Holy shit, now what?”

See The 15 Best Video Game Graphics of 2014

Hirai began an ambitious restructuring of Sony over the three years that followed. He quickly announced a “One Sony” structure that built on Stringer’s convergence with an emphasis on communication and joint decisions among siloed divisions. He focused the electronics business on mobile, gaming and imaging products. Over time, he cut thousands of jobs, sold off the Vaio PC unit, separated the ailing TV business into its own company and overhauled the smartphone lineup.

All of this added to financial losses with restructuring charges and made for a tumultuous 2014. But the low point came last November, with the infamous hack that left sensitive documents from Sony Pictures Entertainment in public view. But it was just around this time when some analysts began voicing their conviction in a Sony turnaround. The turnaround painstakingly plotted by Stringer and Hirai was finally bearing fruit.

That became more evident when Sony reported its most recent earnings. There were encouraging signs in the past year’s finances, like revenue rising 6% and the TV business posting its first profit in 11 years. But the better news was in the cautious forecast for the coming year.

MORE: These Are the Fastest Growing Cities in America

The bulk of the restructuring was behind Sony, CFO Kenichiro Yoshida said, and while revenue may decline 4% this fiscal year, operating profit would rise fourfold to $2.6 billion, its highest profit since 2008. Hirai had earlier projected net income to rise above $4 billion by 2018, which would be its biggest profit since 1998, before the great fall began.

There’s still some restructuring to do. The revenue decrease this year will come largely from Sony’s move away from mid-range mobile phones to focus on the high end of the market. While camera sales continue to decline, Sony is seeing strong growth in imaging sensors used in smartphones. Overall, Sony will be a smaller company in terms of revenue but with bigger sales and slow, steady move from aging markets into growing ones.

A turnaround needs more than cost cutting and restructuring. Sony has a long road ahead to go from playing catch-up in technology markets to playing a leading role in new ones. That step requires a lot more work, but Sony’s return to profitability makes a major turnaround as feasible as it’s been in more than a decade.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com