It’s known that the response to the most recent Ebola outbreak, which as of Tuesday had infected more than 27,000 people and killed 11,130, was far too slow. Now, a new study suggests that even once they got started, their approach to curbing the spread wasn’t the most efficient or effective.

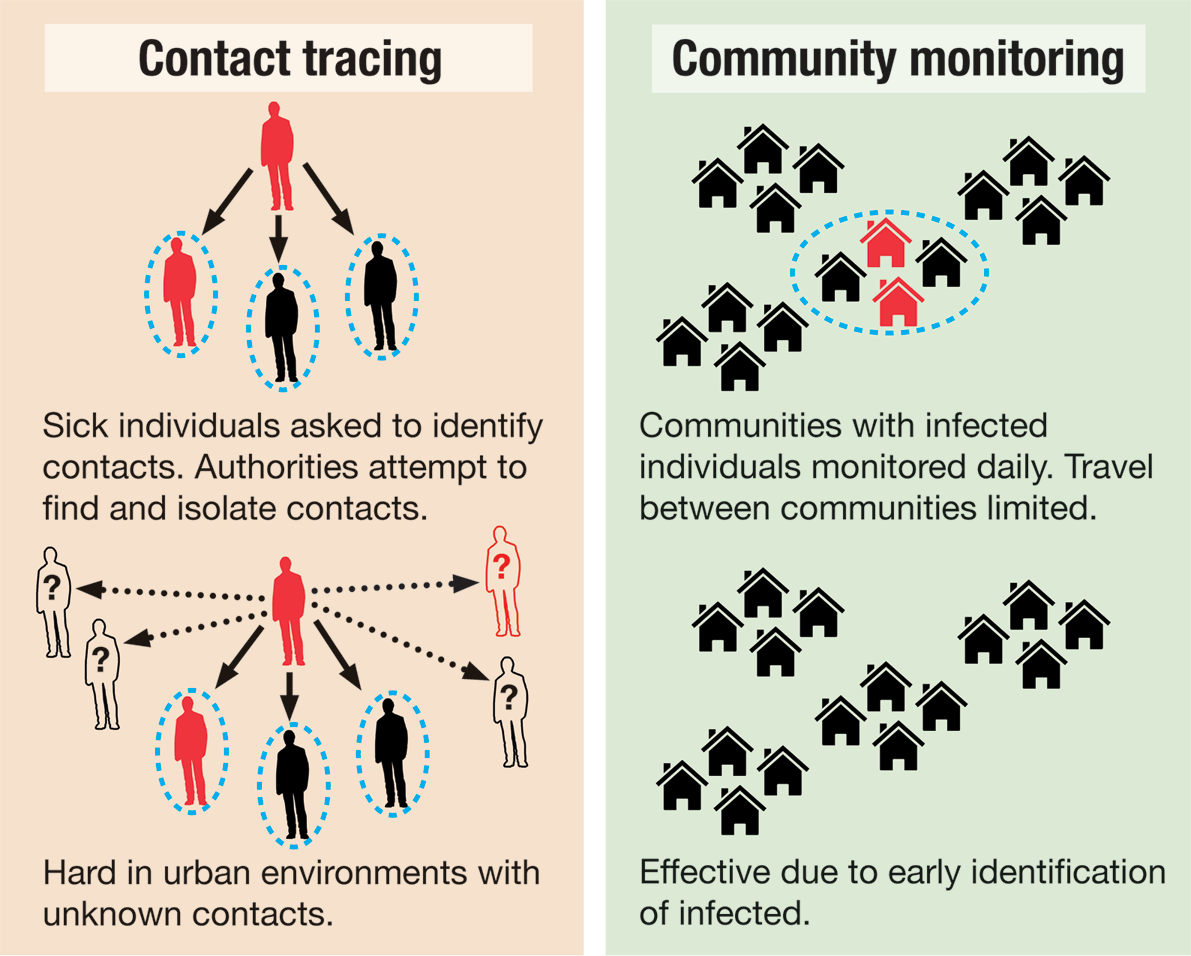

One of the staples of infectious disease outbreak responses was contact tracing: finding everyone who comes in direct contact with a sick person. And it makes sense that health authorities would employ that in this outbreak, since it’s proven in the past to be an effective way to contain the spread of a virus. However, experts at the New England Complex Systems Institute released new research Tuesday that argues contact tracing wasn’t the best approach.

Yaneer Bar-Yam, founding president of the Institute, and his colleagues conducted in-depth mathematical simulations that found that a community-wide response that monitors entire groups of people—rather than tracking down individuals who may or may not have been exposed to the virus via an infected person they had contact with—could have been more efficient.

In the simulations, the researchers accounted for a wide variety of factors and ultimately concluded that a response that focused on community-wide monitoring—for instance, going door-to-door to check on people in a given area as well implementing travel restrictions—would have been more effective than tracking down contacts of infected people one by one. The objective of a community response, they write, is to progressively limit the disease to smaller and smaller geographical areas, while simultaneously sending in resources.

“You treat the whole community as if it might have been in contact with someone,” says Bar-Yam. “Trying to figure out who [an infected person] was in contact with doesn’t make as much sense—and it’s not as cost effective as saying, ‘Well, everyone may have been in contact with these people, so we better check all of them.'”

One of the most telling parts of Bar-Yam’s study was when the researchers looked at what happens when people do not comply with the health guidelines that are put in place to curb an outbreak. After all, no matter how many times people are told what to do, it’s hard to persuade them to stay away from public areas, for instance, or to avoid travel to at-risk places. They found that community-wide monitoring is successful at ending the outbreak even if there’s only 40% compliance.

“You will save more lives if you have higher conformity,” says Bar-Yam of community monitoring, adding that, “from the macro picture you’re stopping the epidemic very rapidly.”

The Key to Liberia Being Ebola Free?

In mid-September 2014 in Liberia, cases of Ebola started to drop significantly. It’s unclear why, but the authors note that around that time, a community-wide approach to stopping the spread of Ebola was taken in Liberia.

Earlier this month the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a report on how it controlled the final cluster, and noted that the response included community-based approaches. And in a report on how Liberia got to zero cases, the WHO writes:

One of the first signs that the outbreak might be turned around appeared in September 2014, when cases in Lofa county, Ebola’s initial epicentre, began to decline after a peak of more than 150 cases a week in mid-August. Epidemiologists would later link that decline to a package of interventions, with community engagement playing a critical role.

In Lofa, staff from the WHO country office moved from village to village, challenging chiefs and religious leaders to take charge of the response. Community task forces were formed to create house-to-house awareness, report suspected cases, call health teams for support, and conduct contact tracing.

“I don’t know how difficult it would have been to implement it earlier,” says Bar-Yam. “Everyone kept saying, ‘Contact tracing is the tried-and-true right way to do this.'” Indeed, since contact tracing has been shown in numerous outbreaks in the past to be effective means of disease containment, that was the de facto strategy in west Africa during this Ebola outbreak.

This study alone cannot prove that health authorities and volunteers were misguided in their use of contact tracing.

Is It Either/Or?

The CDC declined to comment about the paper specifically, but spoke to TIME about the agency’s use of contact tracing and community monitoring. “When you are able to understand the connections [between people], while imperfect, you understand who is most likely to be infected and you are able to follow them,” says Jonathan Yoder, an epidemiologist with the CDC who responded to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. “At the end, it was really important that nothing was missed. One contact can start a whole other outbreak. I don’t know that it’s one or the other. I think the approach of engaging communities is really important.”

Bar-Yam says his work shows that there is an alternative approach to contact tracing alone, and that it appears to work—possibly more quickly than contact tracing, if done early enough.

The paper also underlines the importance of being nimble when it comes to dealing with outbreaks of infectious diseases like Ebola. “Everyone thinks in terms of statistics of prior events. Everyone looks at prior history and says ‘What are we going to be able to expect in the future based on what happened in the past?’” says Bar-Yam.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com