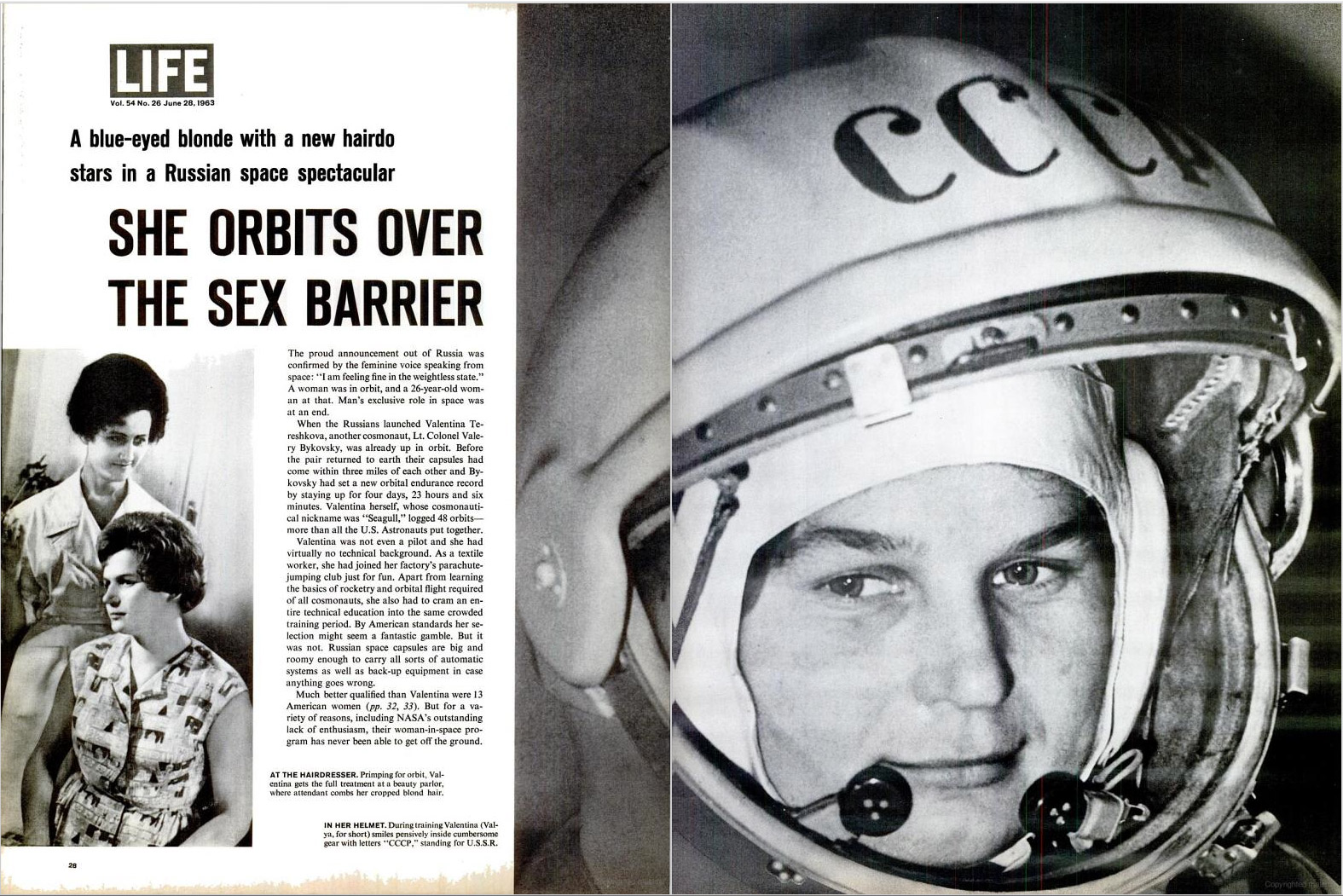

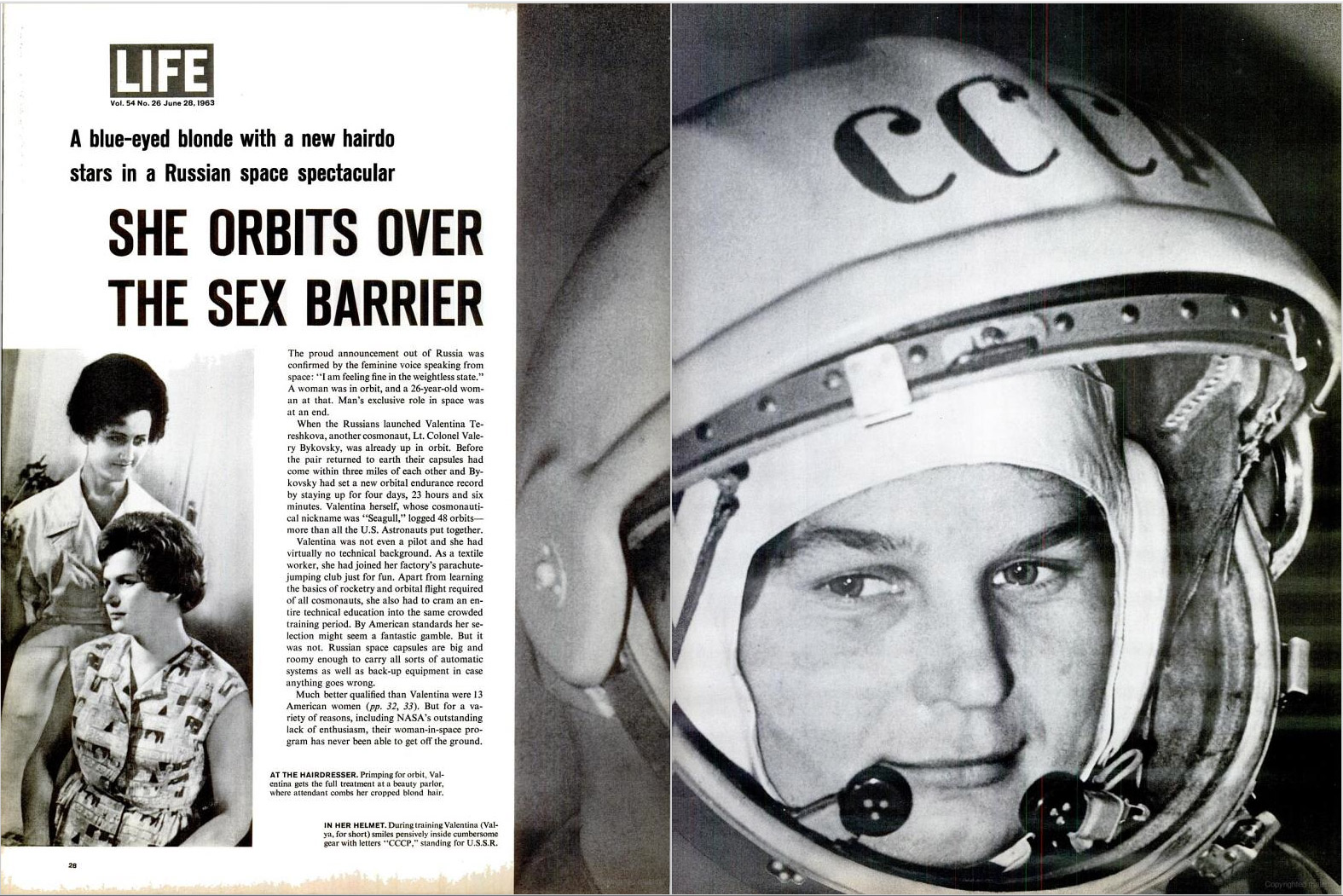

On June 16, 1963, 26-year-old Valentina Tereshkova was launched into space, beginning a three-day expedition during which she would orbit the earth 48 times. Tereshkova, a textile worker and member of her factory’s parachute-jumping club, had responded to a call for women interested in going to space. Among 400 applicants, she was selected for both her physical qualifications and her father’s legacy as a Russian war hero. She underwent months of intense training before earning the title of first woman in space.

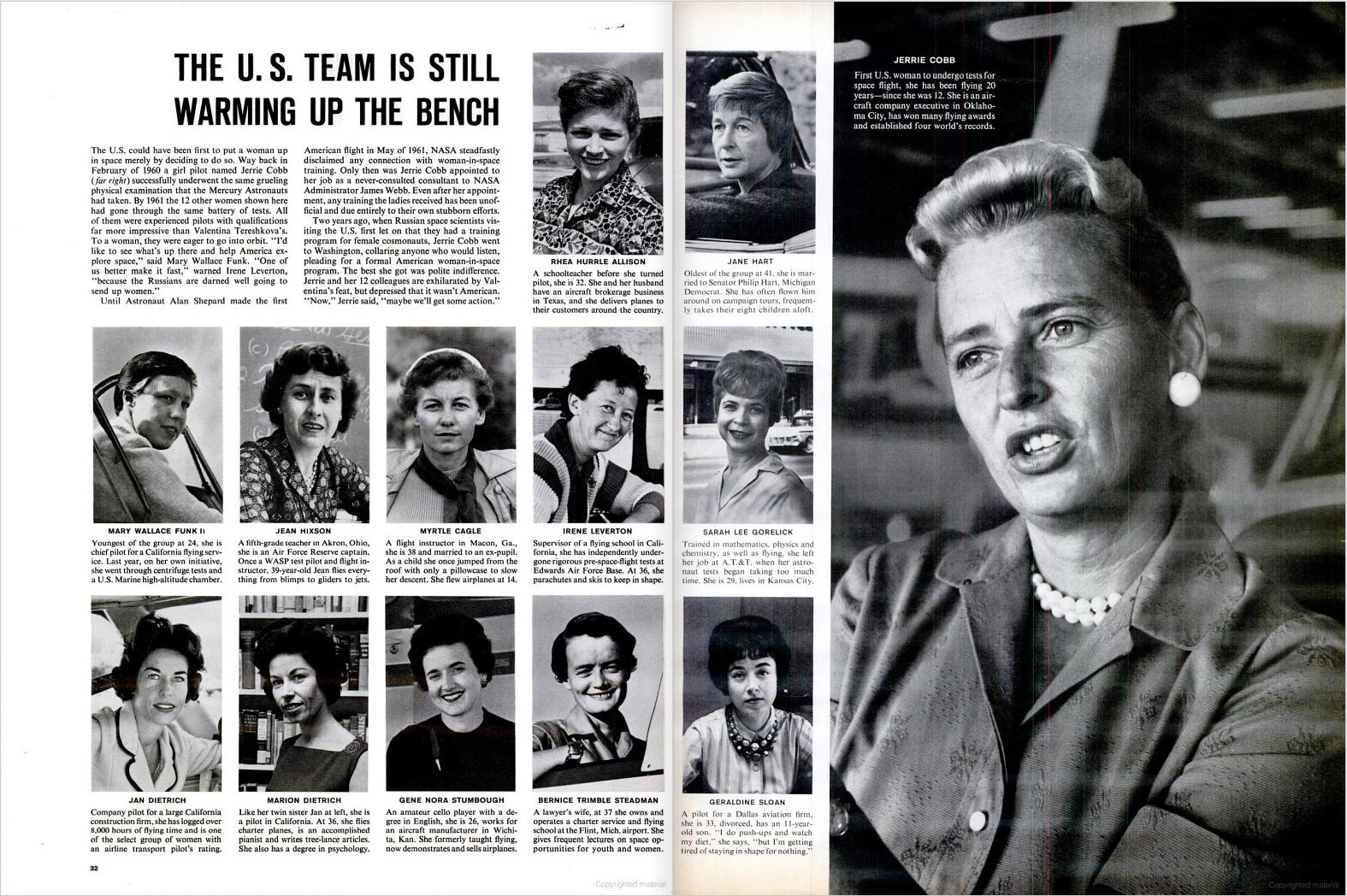

When LIFE featured Tereshkova later that month with the headline, “She Orbits Over the Sex Barrier,” the magazine was quick to point out that the U.S. had a deep bench of female astronauts “more qualified than Valentina.” For several reasons, though, “including NASA’s outstanding lack of enthusiasm, their women in space program has never been able to get off the ground.”

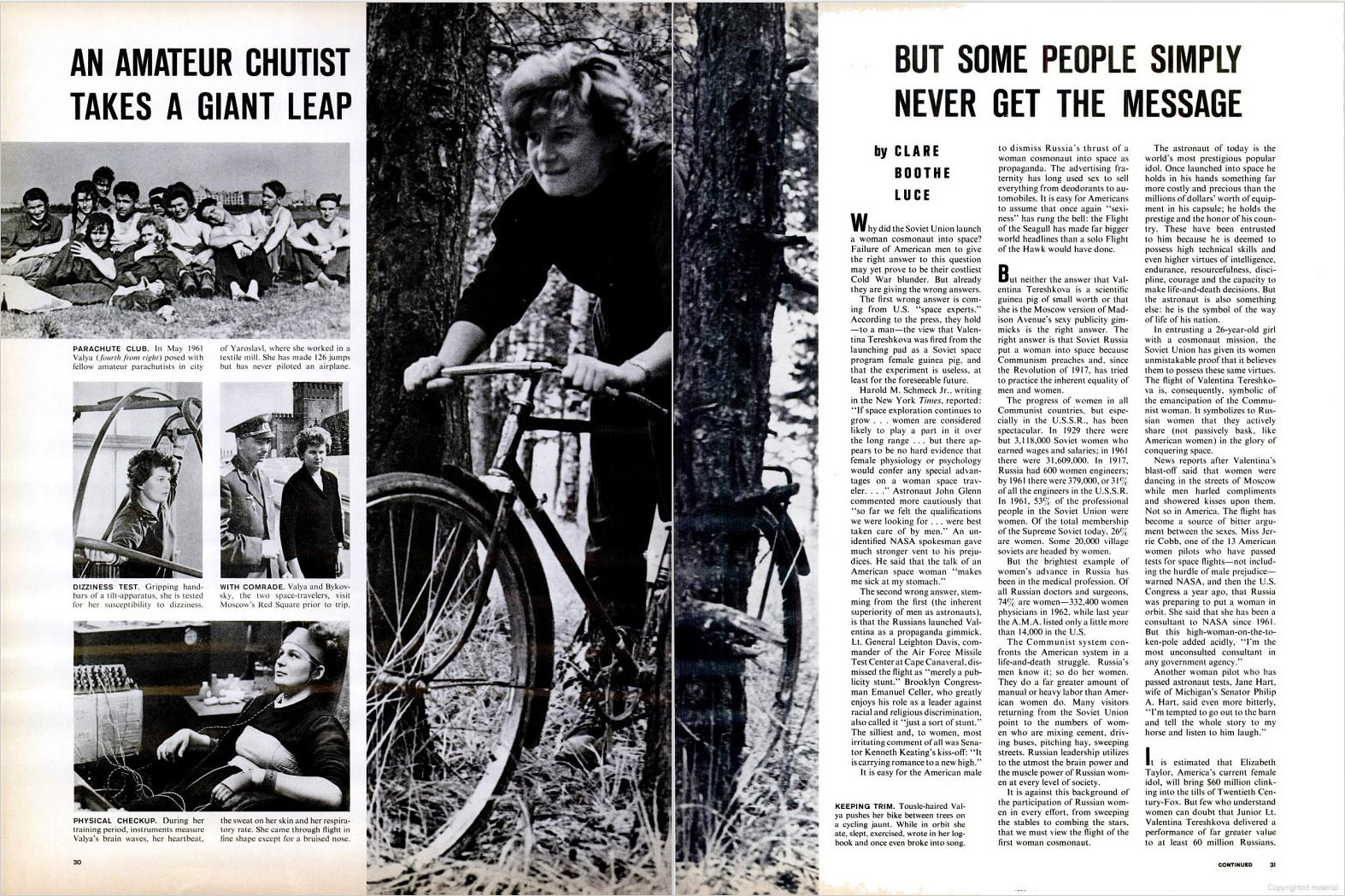

Clare Boothe Luce—writer, politician and wife to LIFE’s publisher Henry Luce—wrote an op-ed speculating as to why the U.S. lagged behind Russia in this arena. Luce referenced several U.S. space experts’ theories before offering her own. John Glenn, one of the Mercury Seven astronauts, posited that “so far we felt the qualifications we were looking for … were best taken care of by men.” Some said Tereshkova was just a Space Race publicity stunt. An unidentified NASA spokesman said the idea of a woman in space made him physically ill.

Boothe’s answer was much simpler: communism. “The right answer,” she wrote, “is that Soviet Russia put a woman in space because Communism preaches and, since the revolution of 1917, has tried to practice the inherent equality of men and women.” As evidence, she pointed to statistics in the field of medicine: In the USSR, 74% of doctors and surgeons were women, whereas they were still a relative rarity in the U.S. Russian woman were expected to participate equally in every level of society, from manual labor to the highest scientific feats.

“The flight of Valentina Tereshkova is, consequently, symbolic of the emancipation of the Communist woman,” Luce wrote. “The U.S. could have been first to put a woman up in space simply by deciding to do so.” Boothe’s argument, lauding communism and blatantly calling sexism on America’s community of space experts, was not only risky, but also pointed to an inequality that wouldn’t swiftly be addressed. Despite a plethora of space-ready female astronauts, it would be another 20 years before America sent a woman, Sally Ride, into space.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com