The Presidential candidates are finally talking about foreign policy, but, not surprisingly, they aren’t yet saying much. “America must lead. We must combat tyranny and defend freedom. Our allies are counting on us. Our enemies are watching.” We’ve heard all this before.

They have good reason, of course, to avoid detailed descriptions of their policy plans. A candidate’s message is crafted to maximize fundraising and vote counts, not to enlighten the public, and foreign policy is the area where candidates are most likely to go light on substance. Even in an uncertain world, the American voter cares much more about hot-button domestic issues like health care, immigration, tax policy, entitlement reform, gay marriage and gun rights than they do about Syria, Ukraine, trans-Atlantic relations, or China.

More importantly, the United States has been a superpower so long that many voters appear to think that successful foreign policy is mainly a test of toughness and will. They don’t see the need to make tough choices—or why those choices will matter so much for the lives and livelihoods of their children and grandchildren.

We’ll hear more about America’s role in the world in 2016, in part because Hillary Clinton served as President Obama’s secretary of state. That encourages Republicans to talk about foreign policy issues that voters would otherwise prefer to ignore. And that’s a good thing, because we need to talk more about foreign policy—and with a new sense of urgency. The next president will make crucial decisions in an increasingly complicated world—and without reliable public support for plans that demand a long-term U.S. commitment.

In my book Superpower: Three Choices for America’s Role in the World, I put forward three possible paths for the future of U.S. foreign policy:

To help voters think about the top candidates and where they fit in on foreign policy, consider the following:

Jeb Bush: Indispensable America

“Everywhere you look, you see the world slipping out of control,” warned former Florida Governor Jeb Bush in February 2015. This was not the first time he has argued that America must lead to set things right. “America does not have the luxury of withdrawing from the world…Our security, our prosperity and our values demand that we remain engaged and involved in often distant places. We have no reason to apologize for our leadership and our interest in serving the cause of global security, global peace, and human freedom. Nothing and no one can replace strong American leadership… …If we withdraw from the defense of liberty anywhere, the battle eventually comes to us.”

This emphatic and unapologetic appeal to defend liberty anywhere it’s threatened comes from a candidate who has coined the term “liberty diplomacy” to describe his foreign policy aspirations. He has called for arms for Ukraine’s government and an aggressive approach against ISIS: “We have to develop a strategy that’s global, that takes them out. Restrain them, tightening the noose and then taking them out is the strategy. No talking about this. That just doesn’t work for terrorism.” While Rand Paul and Ted Cruz often speak to the Libertarian leanings of younger Republican voters with assertions of Constitutional limits on executive power, Bush, who has never served as a legislator, offers a more traditional Republican appeal for strong presidential leadership for a more forceful American role in the world.

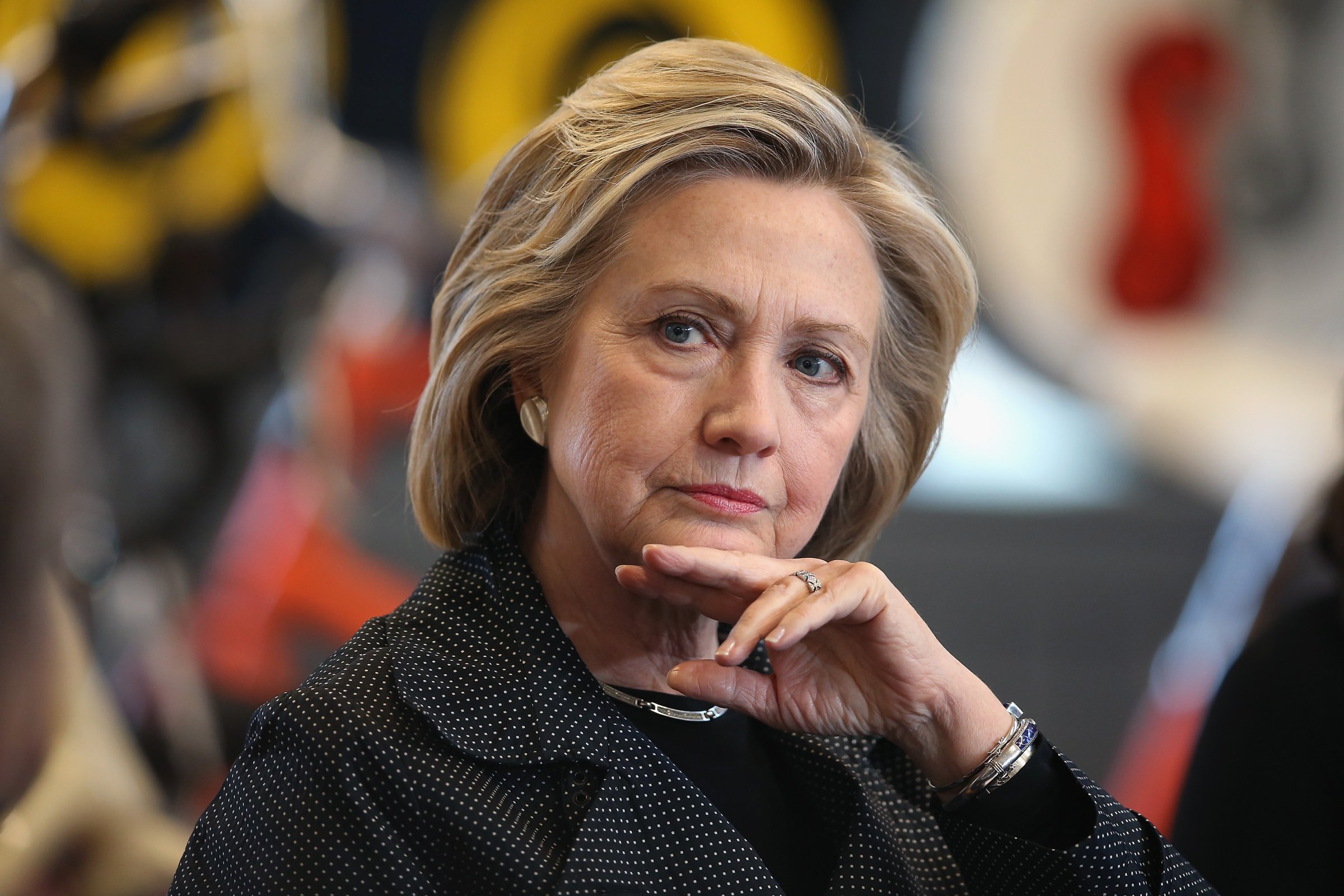

Hillary Clinton: Edging from Moneyball to Indispensable America

As President Obama’s secretary of state, Hillary Clinton offered a Moneyball-inspired vision of America’s future, one that set aside risks in favor of opportunities, emphasized economic rather than military power, and focused on political and economic inroads in East Asia rather than a global assertion of American values. She firmly rejected an Independent America approach: “There are those on the American political scene who are calling for us not to reposition, but to come home. They seek a downsizing of our foreign engagement in favor of our pressing domestic priorities. These impulses are understandable, but they are misguided. Those who say that we can no longer afford to engage with the world have it exactly backward — we cannot afford not to.”

She was a forceful advocate of “economic statecraft” which she described like this: “first, updating our foreign policy priorities to take economics more into account; second, turning to economic solutions for strategic challenges; third, stepping up commercial diplomacy — what I like to call jobs diplomacy — to boost U.S. exports, open new markets, and level the playing field for our businesses; and fourth, building the diplomatic capacity to execute this ambitious agenda. In short, we are shaping our foreign policy to account for both the economics of power and the power of economics.” To promote a “pivot to Asia,” she said that “The future of politics will be decided in Asia, not Afghanistan or Iraq, and the United States will be right at the center of the action.” She argued that “A focus on promoting American prosperity means a greater focus on trade and economic openness in the Asia-Pacific. The region already generates more than half of global output and nearly half of global trade.” She favored a pragmatic “reset” of relations with Putin’s Russia.

But in anticipation of the 2016 presidential campaign, Clinton’s rhetoric has become more universalist and more ambitious. In her book Hard Choices, she wrote that “To succeed in the 21st century, we need to integrate the traditional tools of foreign policy–diplomacy, development assistance, and military force–while also tapping the energy and ideas of the private sector and empowering citizens, especially the activists, organizers, and problem solvers we call civil society, to meet their own challenges and shape their own futures. We have to use all of America’s strengths to build a world with more partners and fewer adversaries, more shared responsibility and fewer conflicts, more good jobs and less poverty, more broadly based prosperity with less damage to our environment.” Voters are left to wonder whether a President Hillary Clinton would pursue a shrewd, targeted foreign policy or one built atop a foundation of comprehensive global leadership.

Ted Cruz: Marching from Moneyball toward Indispensable America

Before he began to hone his message for a presidential campaign, Texas Senator Ted Cruz was an articulate advocate of a Moneyball foreign policy. In 2013, he opposed action against Syria’s Bashar al-Assad. “Assad’s actions, however deplorable, are not a direct threat to U.S. national security. Many bad actors on the world stage have, tragically, oppressed and killed their citizens, even using chemical weapons to do so. Unilaterally avenging humanitarian disaster, however, is well outside the traditional scope of U.S. military action….it is not the job of U.S. troops to police international norms or to send messages…U.S. military force should always advance our national security.”

It’s hard to imagine a more forceful articulation of Moneyball foreign policy. Yet he added that “No other country is capable of putting together a coalition of like-minded nations and leading the fight against tyranny.” Political rhetoric aside, advocates of Moneyball America don’t call for a fight against “tyranny.”

Yet, as campaign season approached, the rhetoric began moving toward an Indispensable approach: “I’m a big fan of Rand Paul. I don’t agree with him on foreign policy. I think U.S. leadership is critical in the world… The United States has a responsibility to defend our values.” Or this: “One of the things [US] Ambassador [to the United Nations Susan] Rice said that was absolutely correct is that America is the indispensable leader. But what our allies are expressing over and over again is that leadership is missing… When America’s weak, when the American President is weak, it leaves our friends and allies vulnerable.” That statement and others like it leave him squarely in the Indispensable camp, where he will likely remain throughout the 2016 campaign.

Rand Paul: Caught between Independent and Moneyball America

Kentucky Senator Rand Paul offers a complex foreign policy vision, one poised uneasily between the Independent America approach his father advanced in past election campaigns and the Moneyball viewpoint more common within the mainstream of the Republican Party. In 2013, he wrote that, “America’s national security mandate shouldn’t be one that reflects isolationism, but instead one that is not rash or reckless, a foreign policy that is reluctant, restrained by Constitutional checks and balances but does not appease.” That’s an excellent articulation of Moneyball foreign policy.

One sentence later, he moves squarely into Independent America territory: “This balance should heed the advice of America’s sixth president, John Quincy Adams, who advised, ‘America goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.’” Anyone who supports Independent America will find truth in this statement: “We should not succumb to the notion that a government inept at home will somehow become successful abroad.” Or this: “We cannot continue to try to bully allies or pay off our enemies. So many of the countries we send aid to dislike us…and openly tell the world they will side with our enemies.”

Paul has, however, supported airstrikes against ISIS and a get-tough approach on Iran, a country he once said was “not a threat. Iran cannot even refine their own gasoline.” Senator Paul often appears uncomfortable with a full embrace of Independent America, but no candidate in the race offers a more forceful defense of this approach on individual questions of policy and principle.

Marco Rubio: Indispensable America

Ironically Florida Senator Marco Rubio, a candidate who often demonstrates an ability to connect with younger voters, appears to have fully embraced the Indispensable America point of view favored by his party’s establishment and so many older Americans. Consider these three statements. On the Middle East: “I always start by reminding people that what happens all over the world is our business. Every aspect of [our] lives is directly impacted by global events. The security of our cities is connected to the security of small hamlets in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia.” On the needs of America’s economy: “We’re 4 to 5 percent of the world’s population. So for us to grow our economy robustly and provide more economic opportunity to more people, we need to have millions of people around the world that can afford to trade with us, that can afford to buy our products and our services.” On relations with non-democracies like Iran, China, and North Korea, Rubio has said that “There is only one nation on earth capable of rallying and bringing together the free people on this planet to stand up to the threat of totalitarianism.” For those who favor an Indispensable America, Marco Rubio is a compelling choice.

Scott Walker: Incoherent America

Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker belongs in the Incoherent file. At times, he talks as if he might embrace the Indispensable. On ISIS, he has said, “We need to take the fight to ISIS and any other radical Islamic terrorists in and around the world….We have to be prepared to put boots on the ground if that’s what it takes…. When you have the lives of Americans at stake and our freedom-loving allies anywhere in the world, we have to be prepared to do things that don’t allow those attacks, those abuses to come to our shores.” During a trip to Britain, Walker answered a question on sending weapons to Ukraine’s government by insisting, “I have an opinion on that … but I just don’t think you talk about foreign policy when you’re on foreign soil.”

Walker has said he would scrap any deal President Obama signs with Iran’s nuclear negotiators, even over the objections of America’s closest allies: “If I’m honored to be elected by the people of this country, I will pull back on that on January 20, 2017, because the last thing — not just for the region but for this world — we need is a nuclear-armed Iran.” Maybe it’s just that candidate Walker is simply a political opportunist. Every candidate is guilty of that. Or maybe he has an unrealistic view of what’s possible. In response to a question about his ability to handle ISIS, Walker once claimed that “If I can take on 100,000 protesters [in Wisconsin], I can do the same across the world.” Let’s hope his worldview has since deepened.

In his new book Superpower: Three Choices for America’s Role in the World, TIME foreign affairs columnist Ian Bremmer diagnoses the drift in U.S. foreign policy—and offers a few alternatives for the next President. But where do you want to see the U.S. go? Take this quiz and find out:

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com