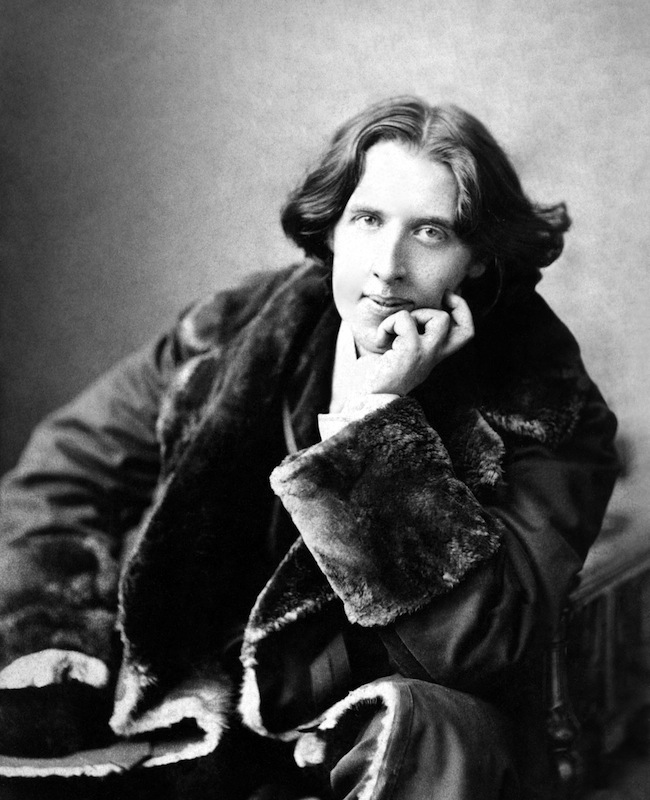

It took guts for Oscar Wilde to take a man to court for calling him a homosexual — or maybe it was hubris, according to the English playwright David Hare, who wrote The Judas Kiss about Wilde.

“He may have thought there wasn’t a situation that he couldn’t talk himself out of,” Hare told TIME in 1998, shortly before the play opened.

But if Wilde really thought that, he was wrong, and he would have discovered so on this day, May 25, in 1895, when he was convicted of “committing acts of gross indecency with certain male persons” and sentenced to two years of hard labor. (His health declined in prison, and he died in disgrace three years after his release, at age 46.)

The Irish poet, playwright and novelist had long relied on his sparkling wit to win over crowds of all kinds, in all circumstances. On an 1882 tour of the United States, for example, he captivated an audience of silver miners at the bottom of a Colorado mineshaft, according to a New York Times review of David M. Friedman’s book Wilde in America.

“I brilliantly performed, amidst unanimous applause,” Wilde reported, not incorrectly, of his reception at the mine.

In 1895, Wilde was at the height of his literary fame — The Importance of Being Earnest had just opened — and well established as London’s most charming dinner guest, when the father of his young lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, publicly accused him of the crime of sodomy.

Wilde took Douglas’ father, Lord Queensberry, to court for libel. He did so against the advice of friends like the journalist Frank Harris, who urged Wilde to drop the case and flee to France until the media storm had blown over, according to Barbara Belford’s book Oscar Wilde: A Certain Genius.

Wilde persisted nonetheless, expecting his own celebrity to win out over the ravings of Lord Queensberry. But the latter’s lawyers dug up enough dirt to get the libel charge dismissed, and to turn the tables on Wilde, who was arrested for being gay, or “committing gross indecency,” in the legal terms of the time.

It didn’t help that he had offended the sensibility of British reviewers five years earlier with The Picture of Dorian Gray. As The New Yorker pointed out in 2011, “no work of mainstream English-language fiction had come so close to spelling out homosexual desire.” The novel became a key piece of evidence against him in court.

Wilde quickly regretted having pressed his case, writing to Douglas from his prison cell, per The Atlantic, “I am here for having tried to put your father in prison.”

He went on to say, with typical eloquence and clarity of vision, that his greatest misjudgment had been to put his faith in a society that celebrated his wit but abhorred his sexuality. He wrote:

The one disgraceful, unpardonable, and to all time contemptible action of my life was my allowing myself to be forced into appealing to Society for help and protection … Of course once I had put into motion the forces of Society, Society turned on me and said, “Have you been living all this time in defiance of my laws, and do you now appeal to those laws for protection? You shall have those laws exercised to the full.”

Read more about the history of Britain’s anti-homosexuality laws, here in the TIME archives: The Unspeakable Crime

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com