Earlier this month, when presenting the upcoming fall TV schedule, a CBS executive described Survivor, which will begin its 31st cycle of episodes in the fall, as “the miracle show, the marathon show.” The series has found a core group of fans who keep its ratings unspectacular but very reliable. While brighter-burning stars get critical attention and social-media love, Survivor, with its two installments a year, chugs along, largely sticking to its formula: Every week, someone is eliminated from the physical and mental competition, until there’s no one left to vote out and a winner is declared.

This is not what one might have predicted when Survivor premiered 15 years ago, on May 31, 2000. The show’s first season, which aired that summer, was an out-of-the-box sensation the likes of which are almost never seen today; by the time the final episode aired, it was one of TV’s most consequential hits, with some 52 million people watching Richard Hatch take home the $1 million prize. By contrast, the season finale of Empire, considered TV’s biggest new hit in years, had 16.7 million total viewers; the Academy Awards (traditionally the highest-rated entertainment broadcast of the year) got 36.6 million viewers this year.

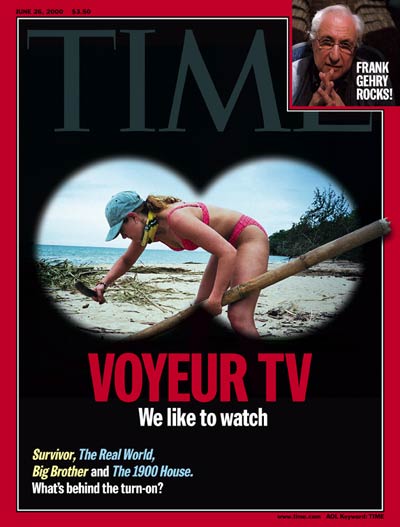

Though it was not the first reality show on television (MTV’s The Real World, for instance, predated it by some eight years), it brought a sense of danger and intrigue to the genre. Describing the appeal of the show, my colleague James Poniewozik, author of TIME’s June 2000 cover story about the phenomenon, wrote that the show’s appeal lay in the “Machiavellian twist” of the voting-off structure, and thus in “the suffering, the mean-spiritedness, the humiliation.”

The sense that Survivor was unusually mean-spirited and harsh has died down in recent years, not least because of the show’s twice-a-year repetition wearing down any opposition. Indeed, Survivor, having largely stayed the same as TV changed around it, is now truly family-friendly viewing, a slightly edgier Jeopardy! compared to the shows it helped to spawn. (Common Sense Media, an advisory group for parents, says it’s appropriate for 11-year-olds and up.) If anything, Survivor seems tamer than ever, as viewers learned after a burn incident in season 2 that doctors are standing by to swiftly deal with any true medical emergencies and as the privation of life on the island has grown less extreme. (No one, lately, has been eating rats.)

Survivor, unlike the cable mainstay The Real World, was a network-TV hit that could be replicated. (The 1970s’ An American Family was a zeitgeist hit, but its premise was all about exposing fissures, with zero upside for the participants. Who’d sign up for a season 2?) The show proved that a very cheaply produced series with the right concept can be huge, a lesson that’s been put into practice by producers of everything from Teen Mom to The Real Housewives of New Jersey.

These shows (along with much else in the reality genre) took from Survivor that the incendiary or shocking could do well; they pushed the envelope further than Survivor, bound by format and by keeping its contestants physically safe, ever could. Within the genre it helped create, Survivor, with its semiannual payouts to contestants who are framed by editing to look like strategic dynamos, is feel-good TV, but things are a lot meaner out there now.

Survivor contestants are people backstabbing one another because that’s the point of the game—and, as time has gone by, the contestants have by and large grown more conditioned to the game, and treat it less personally. There are exceptions, like a recent incident in which one contestant viciously mocked another for being single, but generally the disputes on contemporary Survivor have a businesslike air. And whatever personal revelations happen on the show, now, feel old-hat; Survivor changed the goalposts on what’s okay to say or do on TV to a degree that new incidents of nudity, betrayal or bickering have lost their power to shock. The proof of the power of early Survivor in quickly changing the culture is that late Survivor seems, now, old-hat.

And its followers in the reality genre, too, are less shocking than pleasantly predictable. Real Housewives are ribald and backstabbing, too, but that’s occluded through that franchise’s general air of pointlessness; they’ve learned all the lessons of Survivor but applied them to a game (of getting airtime, fans and potential endorsement deals) that never really ends. “More abstract and worrisome is the overall message the shows send: that life is an elimination contest, that difference means discord,” Poniewozik wrote in 2000. This message seems to have been sent loud and clear by Survivor; all of the candid reality shows in its wake treat the comings and goings of life like a game. No wonder Survivor seems nice by comparison. The wins, there, are about merit.

At the time Survivor first came on, its future and that of its genre’s were uncertain. It seemed just as likely that what Poniewozik called “VTV” or “voyeur television” would produce a consistent stream of world-beating hits as it did that, per TIME in 2000, “viewers may reject VTV altogether before long.” Neither prediction came true; reality television and Survivor both simply chug along. Big Brother, Fear Factor, The Amazing Race and a suite of cable series dedicated to probing the inner(-ish) lives of subcultures from pampered wives to Jersey Shore denizens, all became, over time, like wallpaper, no longer exceptional merely for existing. The only other major reality hits have been in the musical-competition variety, one that owes more to classic game shows than to any Survivor innovation other than low cost (although, with American Idol‘s early judge Simon Cowell, the genre tried to tap into a vein of venal nastiness that was pretty Survivoresque).

Even shows that aren’t megahits can provide enough cash to justify their existence (with the exception of Idol, which pays its celebrity judges big money and whose sagging ratings forced the show’s recent cancellation). By the standards of cable TV, The Real Housewives is, in its own way, as much a “miracle show” as Survivor, endlessly reiterating old feuds year after year, feuds that are meaner and darker than any vote-off that’s happened on CBS. Reality TV is, today, modeled after Survivor in one key regard; it all (with the exception of The Voice, still a hit) rates perfectly okay. This is the real miracle of Survivor: It just keeps going—and, so far at least, where it goes an entire genre follows.

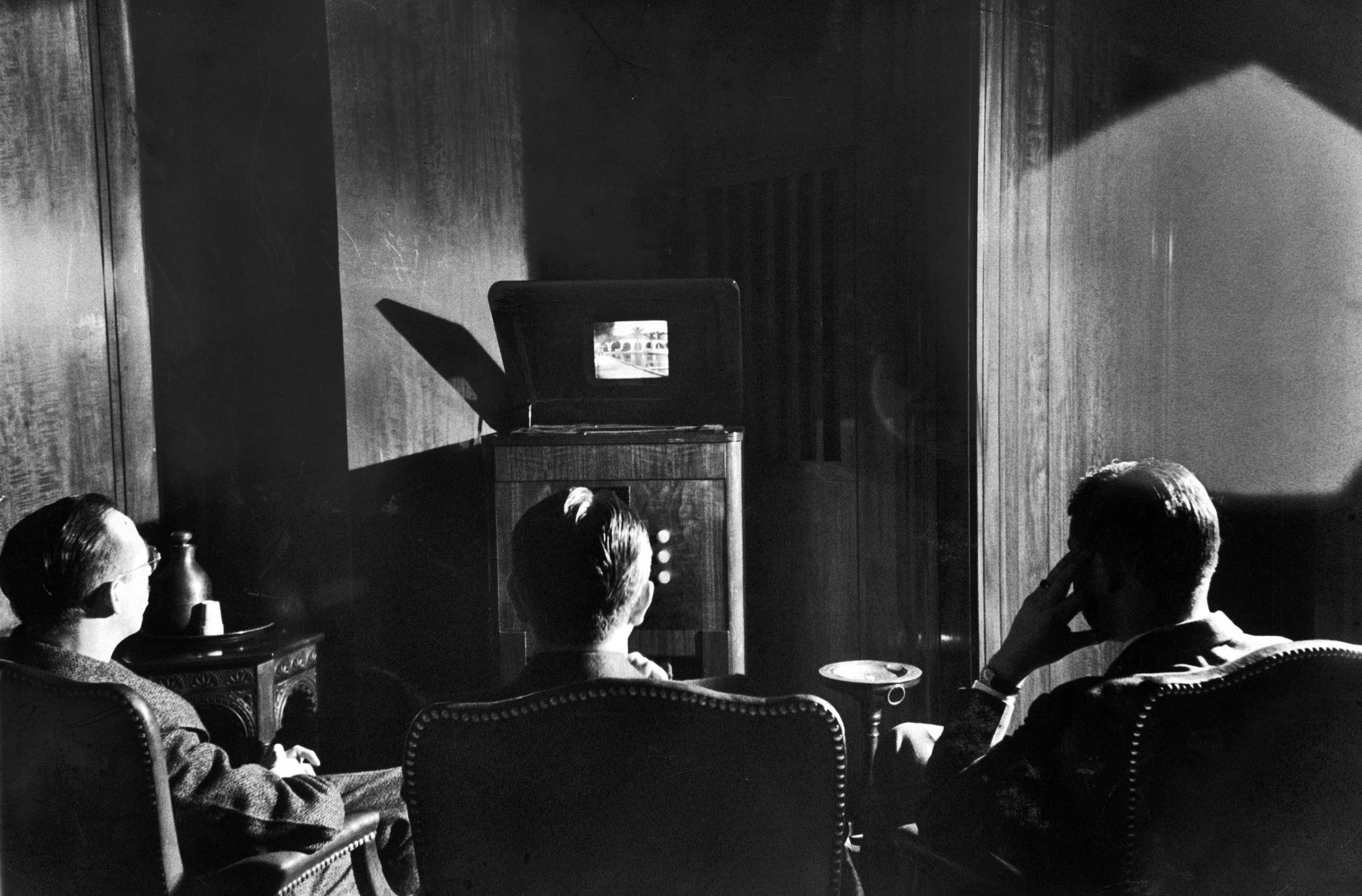

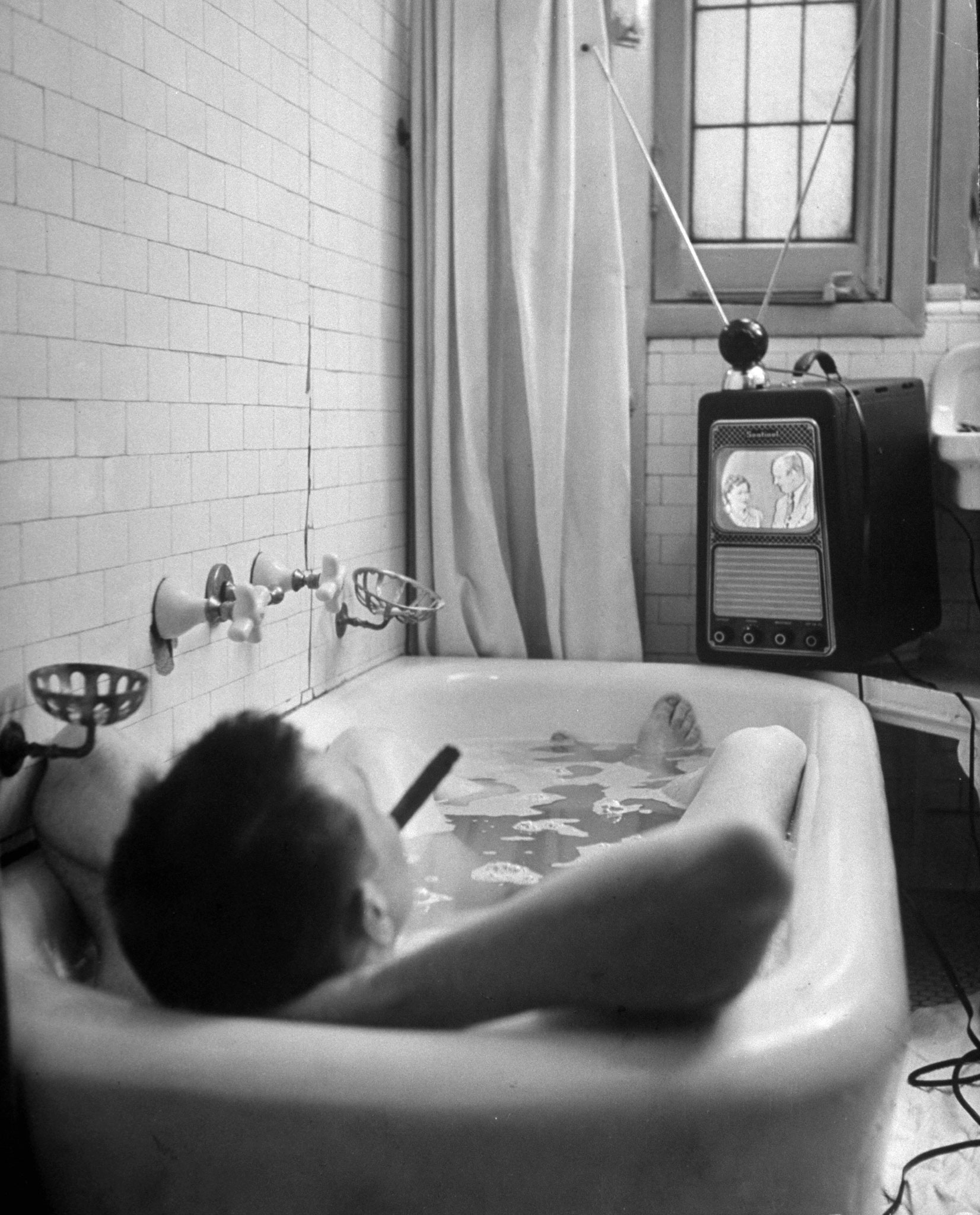

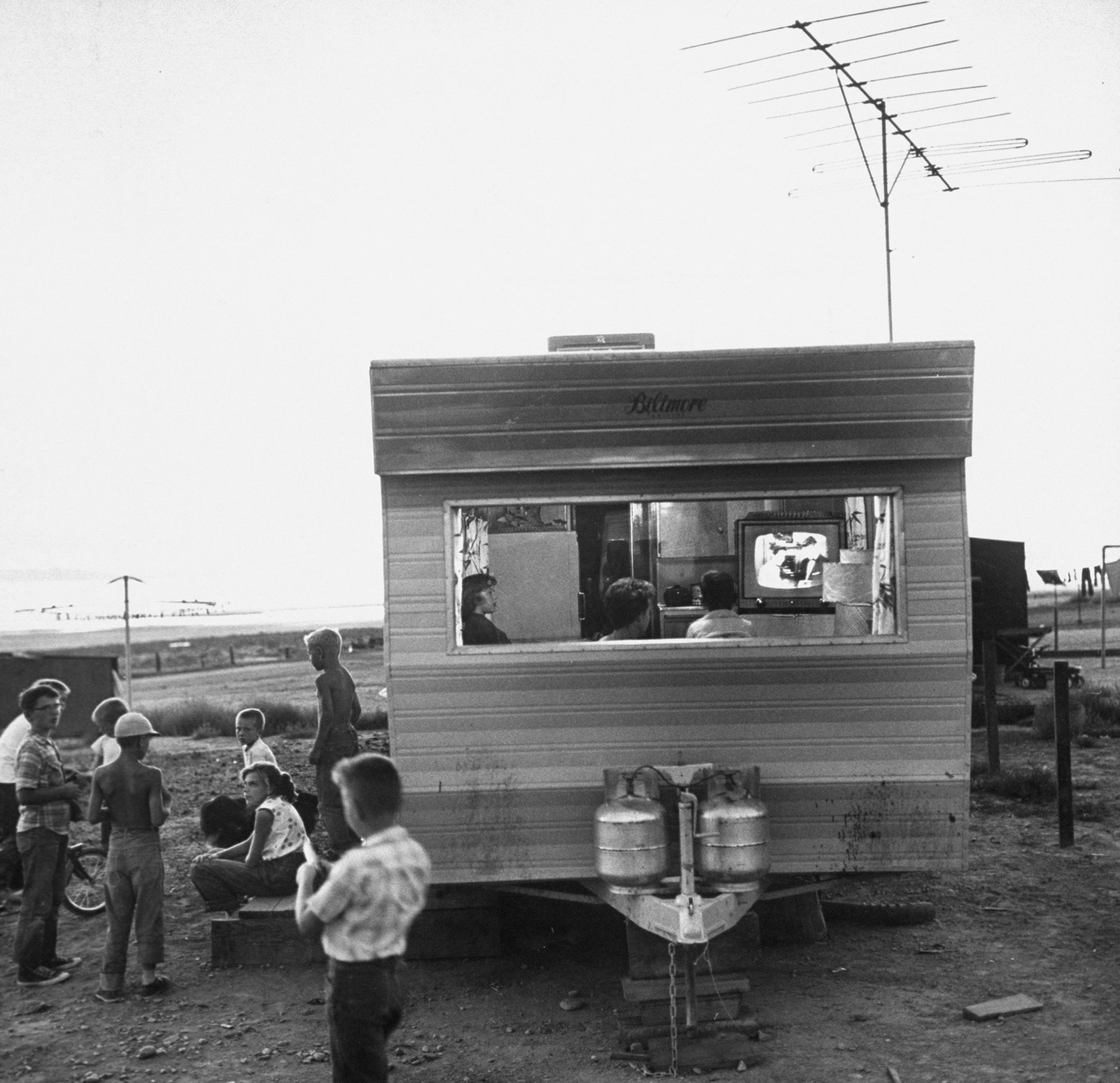

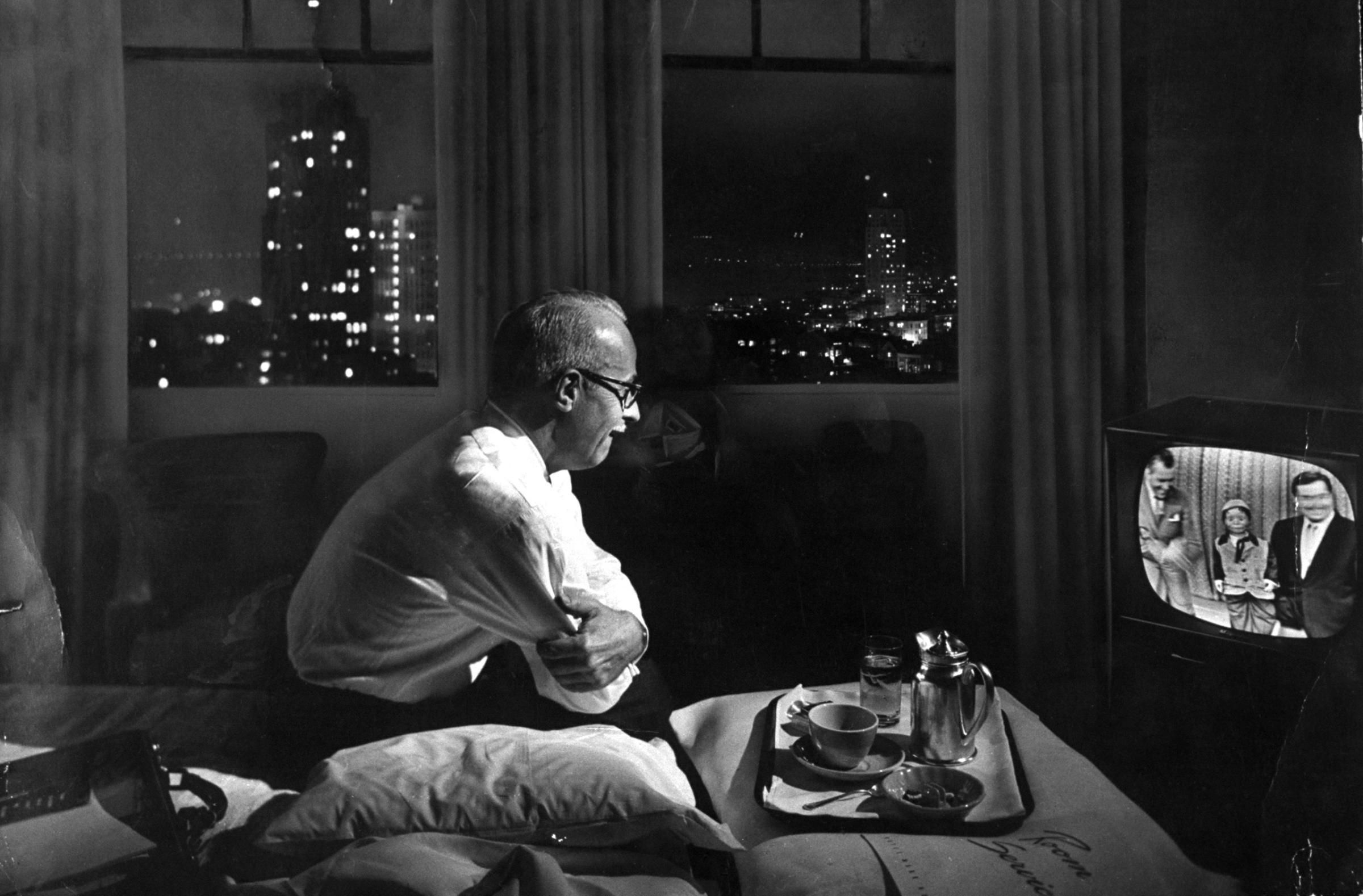

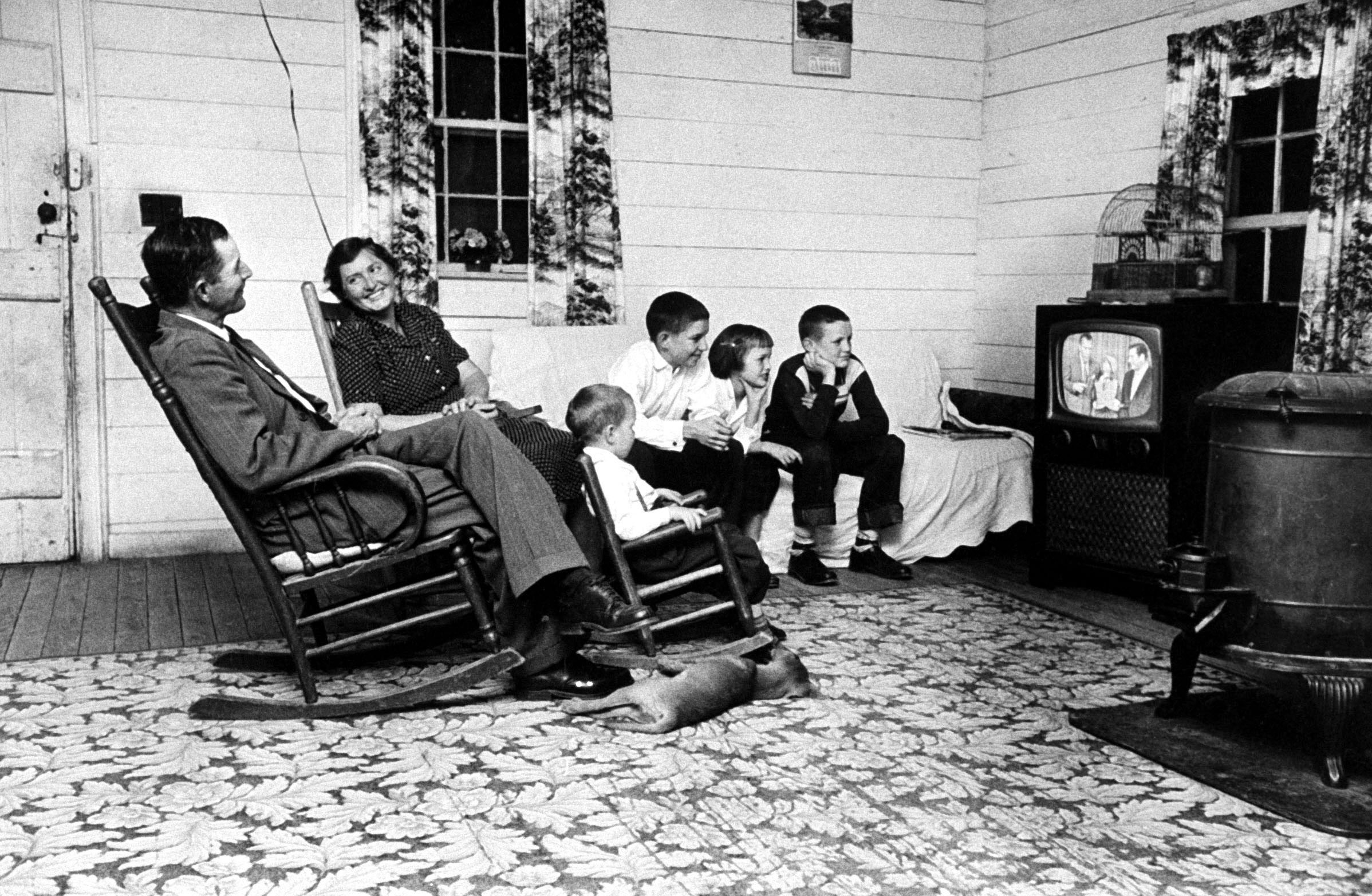

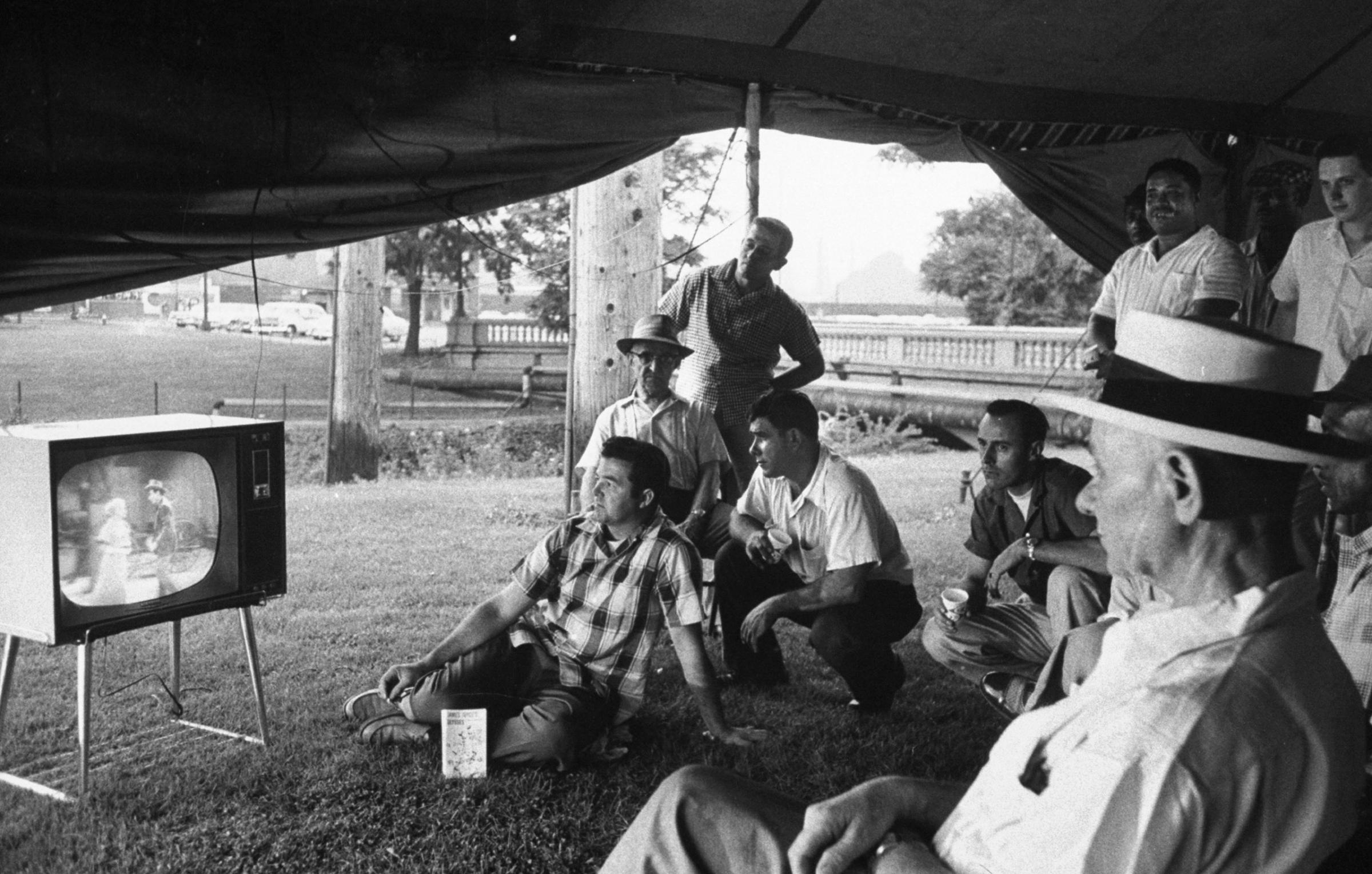

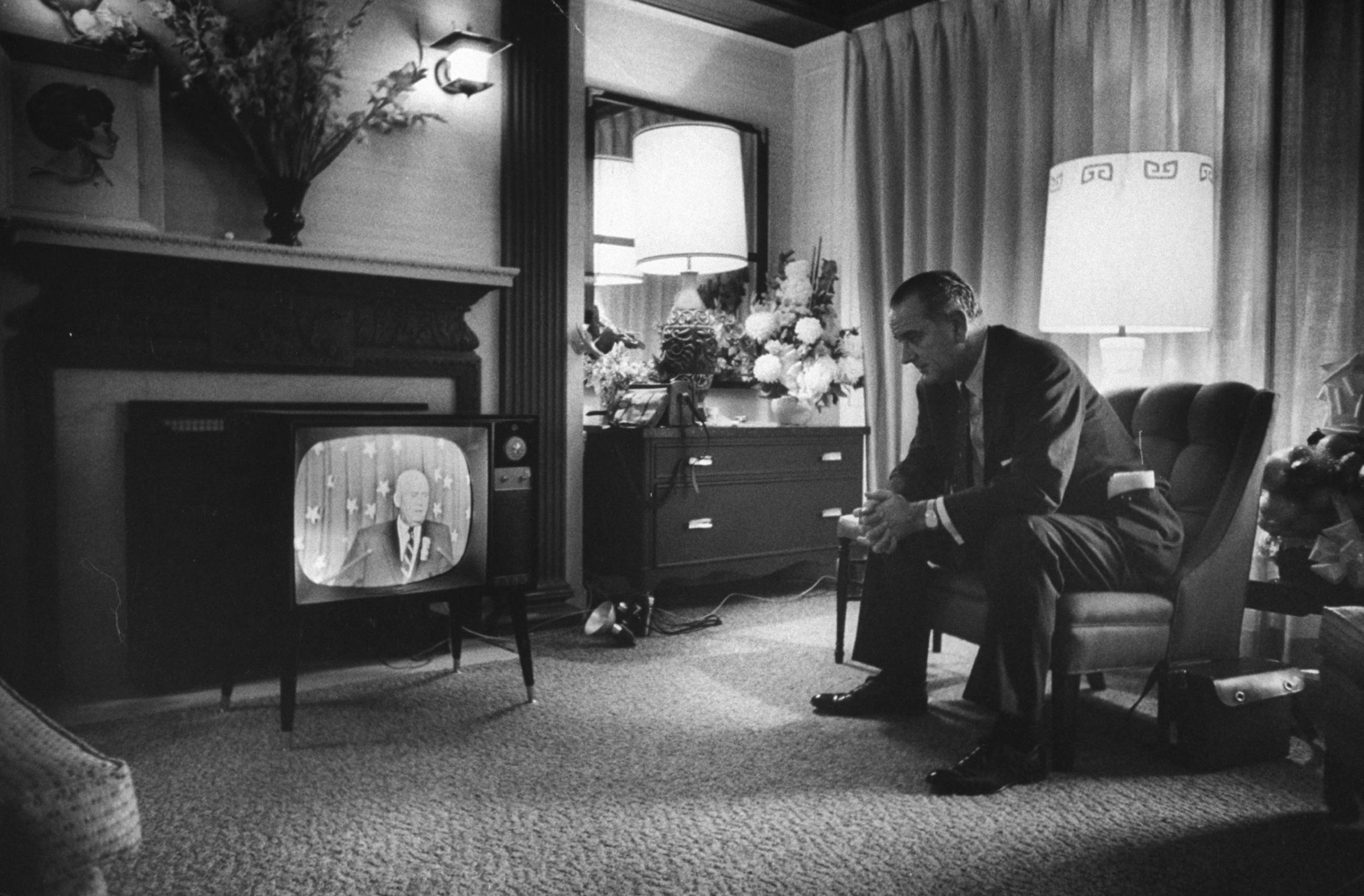

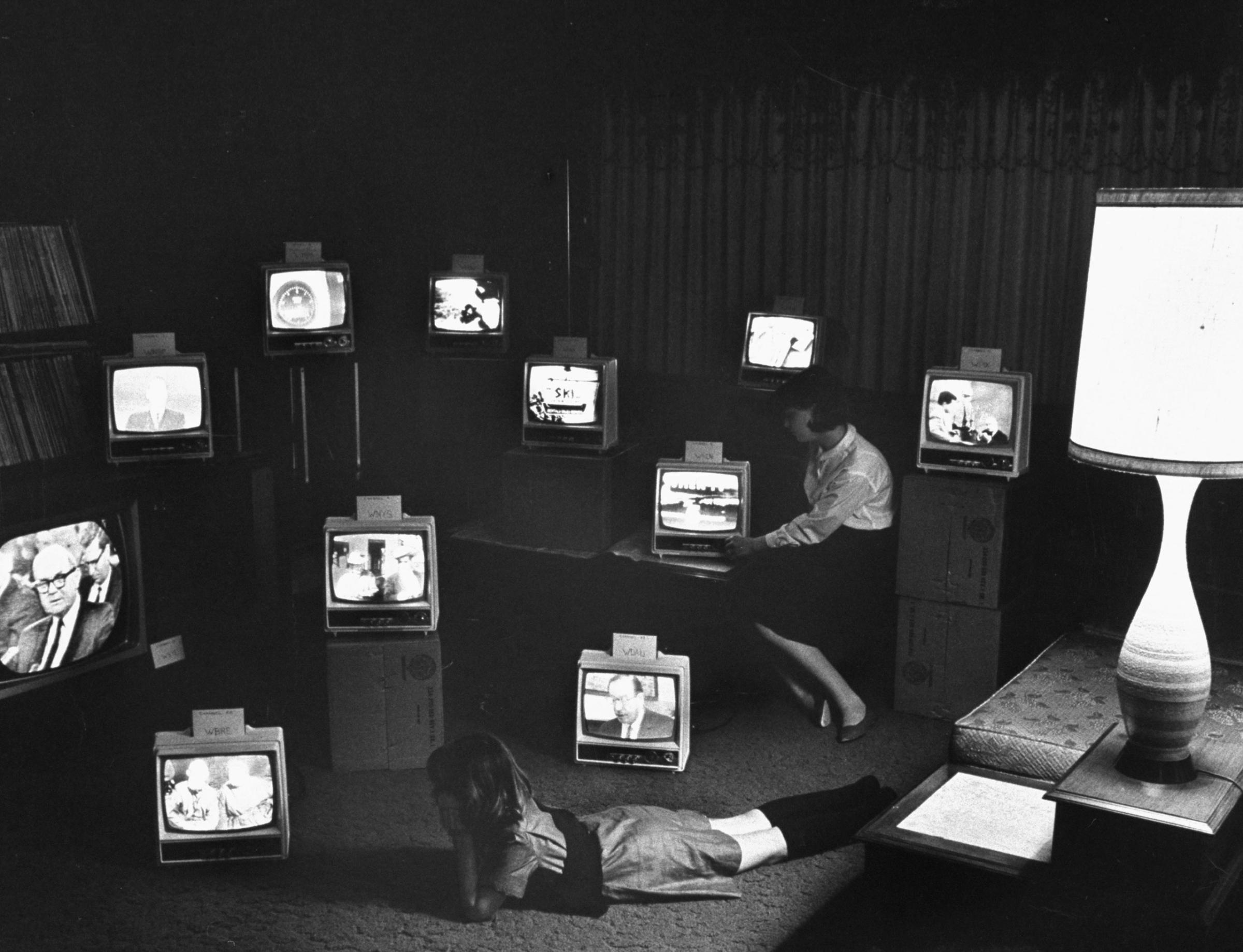

LIFE Watches TV: Classic Photos of People and Their Television Sets

![Jacob A. Malik [Misc.] A group of swimmers at an indoor pool watch the Russian ambassador to the United Nations, Jacob Malik, filibustering in the UN Security Council in 1950.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/141113-vintage-television-photos-07.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Mrs. Malcolm S. Carpenter [& Family] Astronaut Scott Carpenter's wife, Rene, and son, Marc, watch his 1962 orbital flight on TV.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/141113-vintage-television-photos-23.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Diahann Carroll [Misc.];David Frost [Misc.];Diahann Carroll;David Frost Actress Diahann Carroll and journalist David Frost watch themselves on separate talk shows. Carroll and Frost were engaged for a while, but never married.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/141113-vintage-television-photos-28.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com