The first night Late Night with David Letterman aired, Bill Murray bounded on stage and vowed to shadow Letterman for the rest of his career. “I know you’re on here late night where nobody can stop you,” he ranted. “‘If it’s the last thing I’m gonna do, I’m gonna make every second of your life from this moment on a living hell.”

Tuesday night, Murray will appear on the penultimate Late Show as Letterman’s last scheduled guest, and there’s an obvious symmetry to it, as well as history; Murray’s walked or flown onto Dave’s stage numerous times over the years. But there’s more to it than that.

In the current print edition of TIME (subscribe to read!) I have an essay about Letterman’s 30-plus years in late night. One point that I ended up cutting for space is that Murray is not just a fitting last guest because he was Letterman’s first. He’s inextricably bound to Letterman because in many ways they’ve had the same career.

When they first emerged nationally, Murray on Saturday Night Live and Letterman in late night, they developed reputations as master smartasses. They were entertainers part of whose acts riffed on the shtick of entertaining: think Murray’s lounge-lizard rendition of the Star Wars theme on SNL. The 1970s SNL and the 1980s Letterman, both grimy New York institutions, had a kind of punk-rock sensibility, puncturing the artifice that had bloated showbiz and stripping TV down to essentials and anarchy. (You could say the same of some other classic early-Dave guests, like Andy Kaufman and Sandra Bernhard.)

Fans responded to that same sensibility in Murray and Letterman, but their detractors saw a similarity too. People who didn’t like Murray thought he used irony as a crutch, using his laid-back delivery to smugly distance himself from, and make himself superior to, his characters and material. Letterman came in for some of the same knocks, as I write in my TIME essay:

To some detractors, Letterman was the culture’s Typhoid Mary of nihilism. In David Foster Wallace’s short story “My Appearance,” an actress is coached on how to succeed on Late Night: “Laugh in a way that’s somehow deadpan. Act as if you knew from birth that everything is clichéd and hyped and empty and absurd, and that’s just where the fun is.”

But to see Murray and Letterman as mere smirkers sold them both short. Murray’s comedy had a well of emotion; Letterman’s “irony” was in fact a passionate response against phoniness. And as their careers went on, they each became that rare kind of performer: the comic who matures and learns to express a kind of wisdom without overturning the schmaltz barrel. Murray kept making funny movies, but as he aged and greyed, he tapped into the melancholy that is often the silent partner of comedy, working with directors, like Sofia Coppola and Wes Anderson, who knew how to bring that out in them.

Letterman, meanwhile, struggled in the ’90s after moving to CBS; he topped Leno in the ratings for a while, but didn’t quite seem to know how to function as top dog rather than underdog. Then in his next decade–maybe not precisely with his heart surgery in 2000, but right around there–he entered his second great period, this time not as a comic bomb-thrower but as a raconteur, a spoken-word essayist. As Letterman aged and mellowed, he may have lost some edge, but he became the one guy in late-night talk who really knew how to talk–be it about 9/11, his 2009 sex scandal, or the mortality of his friend and guest Warren Zevon.

Latter-era Letterman and Murray weren’t two wise guys getting sappy in their old age. They were two artists mastering their instruments. I can think of no better way to say goodbye than to hear them duet one more time.

Bill Murray is Dave’s first guest (1982)

For Letterman, Murray has dressed like Liberace, a Kentucky Derby jockey and a Renaissance fop. His first visit set the tone of the show when, after a long rant in which Murray decried the host’s “mind games,” Letterman responded, “Now that you’re well-known, is it harder to be funny?”

Andy Kaufman challenges wrestler Jerry Lawler to a match (1982)

In a hoax bit, comedian Kaufman got pro wrestler Lawler to slap him in the face as Letterman smirked behind the desk. The stunt confirmed Dave’s status as a comedy chaos magnet—a master at remaining calm while hysteria swirled around him.

Dave gets dunked in a suit made of 3,400 Alka-Seltzers (1984)

What some do for science, Dave did for comedy. With a snorkel and goggles in place, Dave was dunked into a fizzy experiment in laughter. He’s helpless in his harness, floating in an effervescent water tank surrounded by the volcanic chaos of bubbles. The experiment was duplicated with the likes of sponges, marshmallows and velcro, showing how far Dave would go for a laugh.

The very first top 10 list (1985)

“Heats.” “Rice.” “Moss.” These were the initial entries in the show’s first Top 10 list, “Things That Almost Rhyme With Peas.” Sometimes presented by politicians, celebrities, sports champions and everyday heroes, the lists—more than 4,600 of them—became Letterman’s signature bit.

Cher calls Dave an a–hole (1986)

Dave’s meta-deconstruction of the late night form led to uncomfortable truths — such as in this segment, where an interview with Cher centered on why it took four years for her to agree to appear on the show. Her casual reasoning — “because I thought you were an a–hole” — became part of the show’s disarming folklore.

Madonna won’t stop stop cursing (March 31, 1994)

Letterman often had a flirty effect on female guests, causing many to leave filters at the door. Here, Madonna and Dave giggled and teased, discussing their underwear and making innuendos. Madonna sweetly told Dave he was a “sick f-ck.” Never has that term sounded quite so loving.

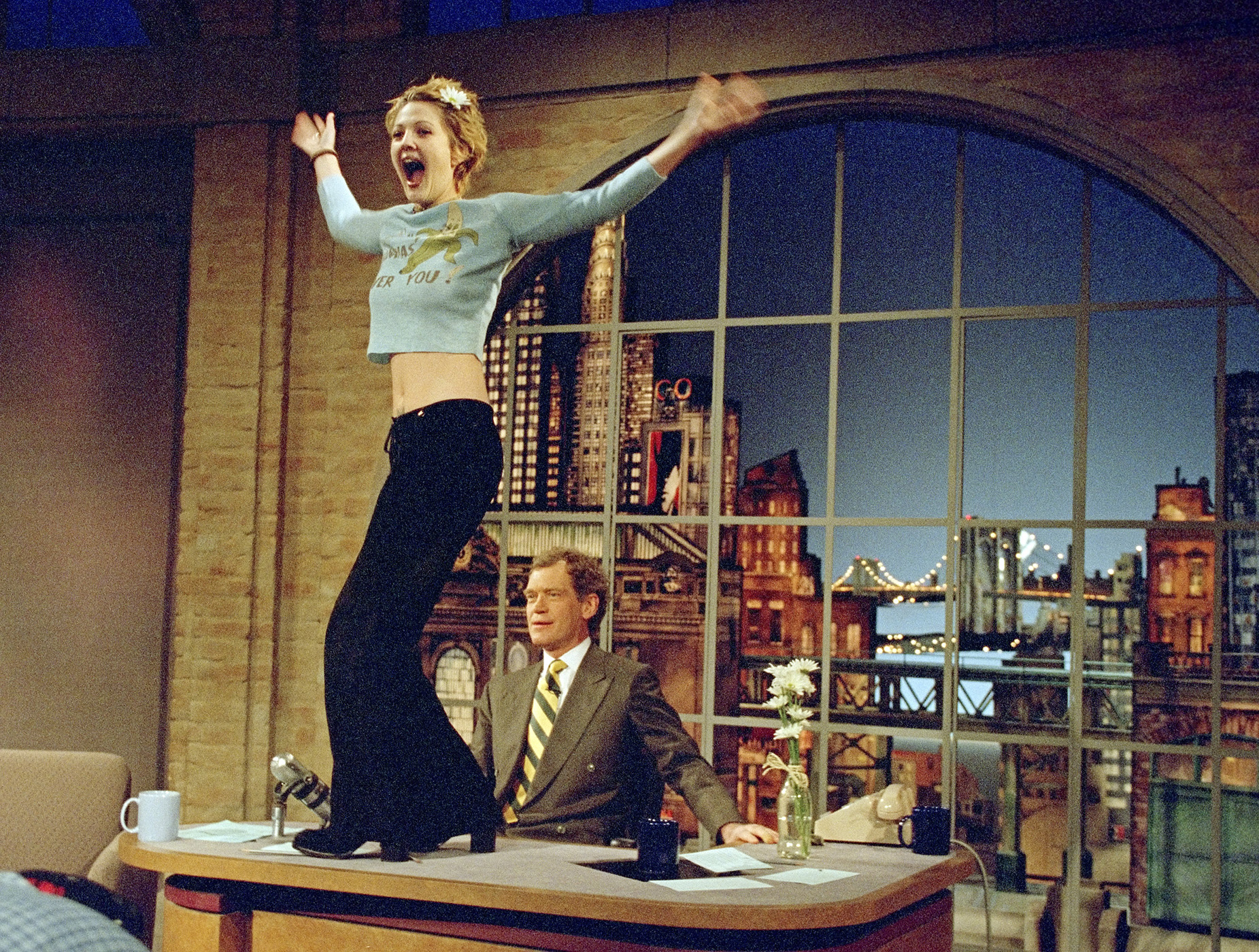

Drew Barrymore flashes Dave for his birthday (April 12, 1995)

In a ’90s version of Marilyn Monroe’s “Happy Birthday, Mr. President,” a 20-year-old, braless Barrymore surprised Dave with a dirty dance on his desk, followed by lifting her shirt. Dave’s reaction—confused but joyful surprise—contributed to the buzz.

Dave gets personal (2000 & 2009)

It’s one thing to be a great host with a knack for comedic moments. It’s another entirely to tap into the national psyche. Dave was long regarded as the king of irony, but that died in 2000, when he dropped all comedic facades to pay tribute to the surgical team that saved his life. It was a rare but powerful moment when Dave the host became Dave the man—a feeling that would be replicated as his messy personal cheating scandal went public nine years later—and his brittle realness drew us even closer to the legend we thought we knew.

Dave gives a heartfelt post-9/11 monologue (2001)

The first late-night host to return to TV, Letterman gave viewers real catharsis following a national tragedy. His eight-minute introduction was halting, honest and vulnerable, tapping into our collective fear and sadness. By the end, he also provided what we needed most: courage and hope.

Joaquin Phoenix is bizarre and rambling (Feb 2009)

Phoenix devised a meta-hoax that found him growing a long beard and claiming to have left acting for hip-hop. Included in this, for reasons not quite clear, was appearing on Letterman like he had no idea what was happening around him. Letterman fired questions at Phoenix despite the guest’s inability to string together a sentence. Ending the interview with, “Joaquin, I’m sorry you couldn’t be here tonight,” cemented the segment as a classic.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com