The deadly shootout between police and biker gangs in Waco, Tex., has put a spotlight on one of American culture’s more confusing distinctions: the difference between motorcycle-loving hobbyists and organized biker gangs. As a former undercover agent told the Associated Press, the public and law enforcement can have trouble distinguishing between two subcultures that share lots of similarities.

That confusion is nearly as old as America’s motorcycle culture. In its early years, the nation’s motorbike market was relatively small. As TIME explained in 1939, it got a boost when Euthrie Paul du Pont, of the famous du Pont family, invested in the Indian Motorcycle Co. The company joined with Harley-Davidson, the other leading U.S. manufacturer, to sponsor the American Motorcycle Association and hold organized races that boosted the popularity of riding. When TIME covered the 1953 National Motorcycle Championship, the magazine found that the participants—drawn from the AMA’s 100,000 members— were “most of them temporary escapees from workaday jobs as mechanics, farmers or motorcycle dealers.”

By then, however, those weekend warriors had been joined in the public imagination by a darker element. In 1947, a fight among bikers led to a notorious melee in Hollister, Calif. That was followed by Frank Rooney’s 1951 story The Cyclists’ Raid, about a fictional violent biker gang, which in turn inspired the 1954 film The Wild One, starring Marlon Brando as an iconoclastic biker. “The audience sits frozen with a growing horror as the abscess of violence swells and swells until the watcher almost cries out for it to burst and be done with,” TIME’s critic wrote of the movie.

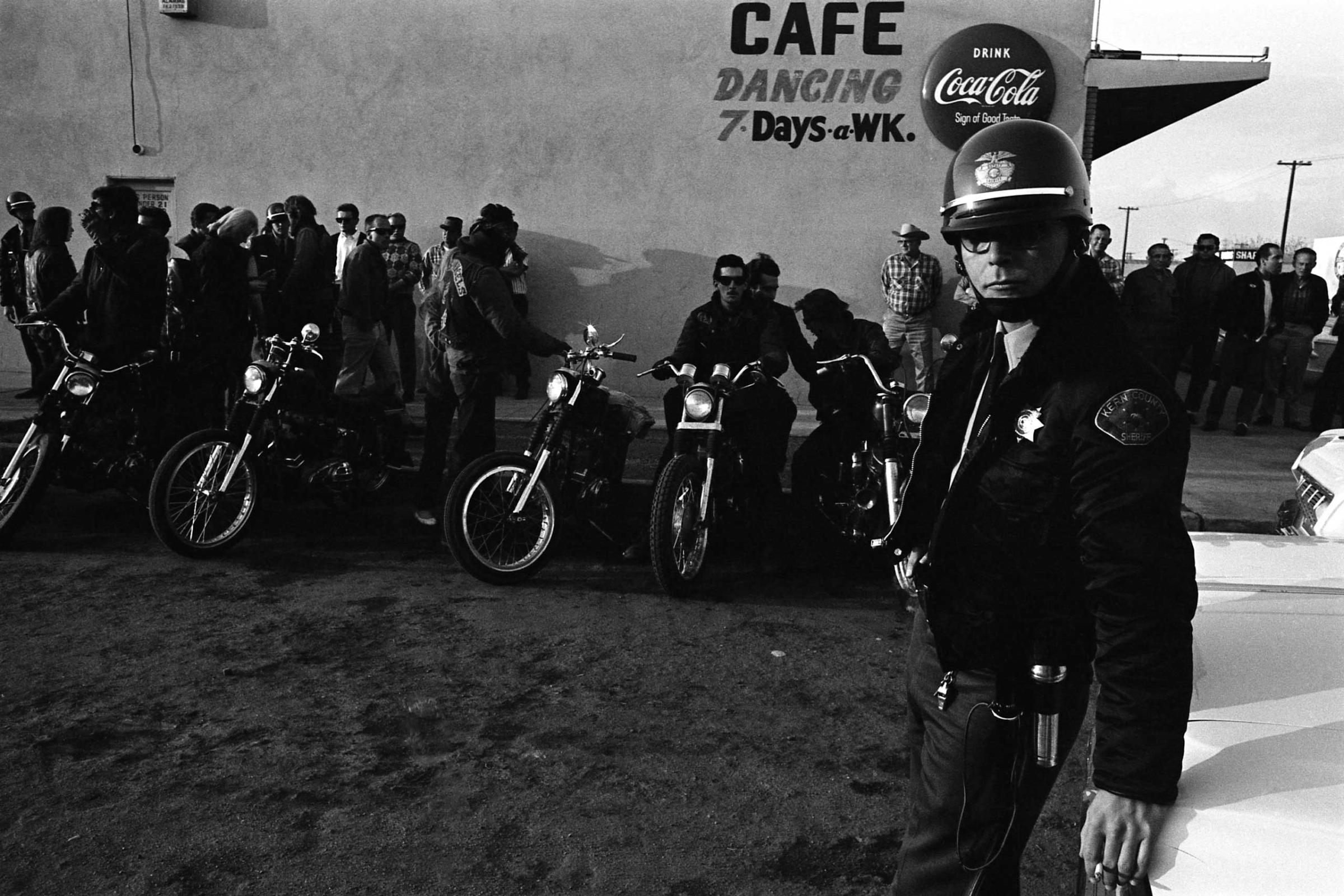

Meanwhile, the AMA tried to keep its distance. In 1957, for example, an AMA event in Angels Camp, Calif., was marred by violence. The small town had agreed to host motorcycle races and had taken precautions—quadrupling its two-man police force—in case of trouble. The safeguards, however, proved inadequate, as TIME reported:

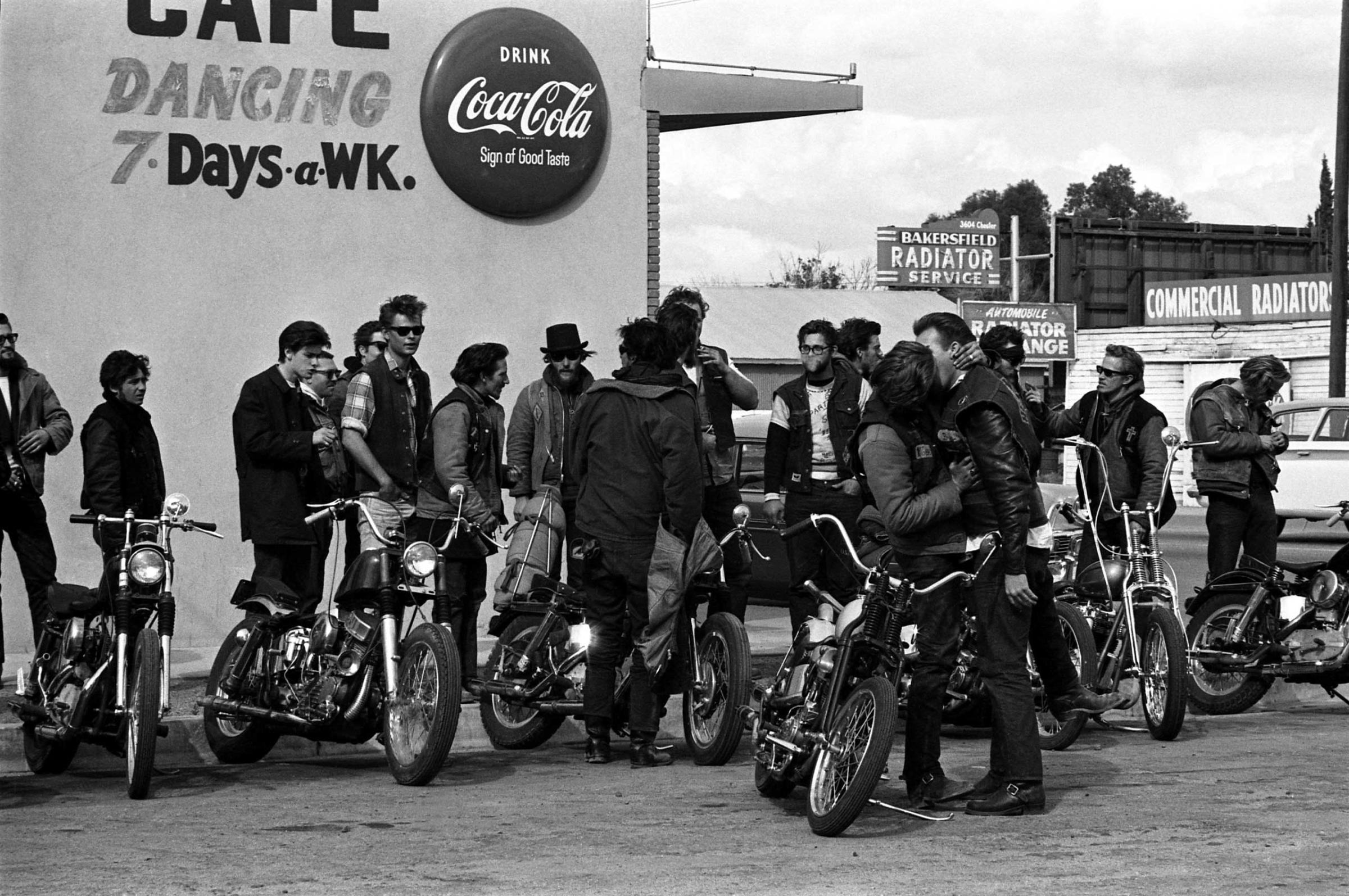

The A.M.A. pitched its camp in the fair grounds just outside town. The hoodlums, their waists girdled by metal chains and their leather jackets emblazoned with gang names—Vampires, Huns, Tartars—parked their cycles on Main Street and tossed their bedrolls beside Angels Camp’s bubbling trout stream. Then they took over the community. They bought all the beer in town (100 cases), buzzed over to neighboring Altaville for more, and for wine. They guzzled fast, tossed empty cans and bottles into gutters. Residents soon found drunks stretched in their doorways. A group trailed a town girl; while one yelled obscenities, the rest of the pack twirled waist chains menacingly to discourage interference. Three of Angels Camp’s four bars shut down; merchants decided to close early. Then came action. Flashing down the Main Street hill with muffler throbbing, a long-haired youngster wheeled artfully through a knot of idlers, snatched a can of beer on the fly. Hundreds of daredevils kicked their starters, ready to meet his challenge.

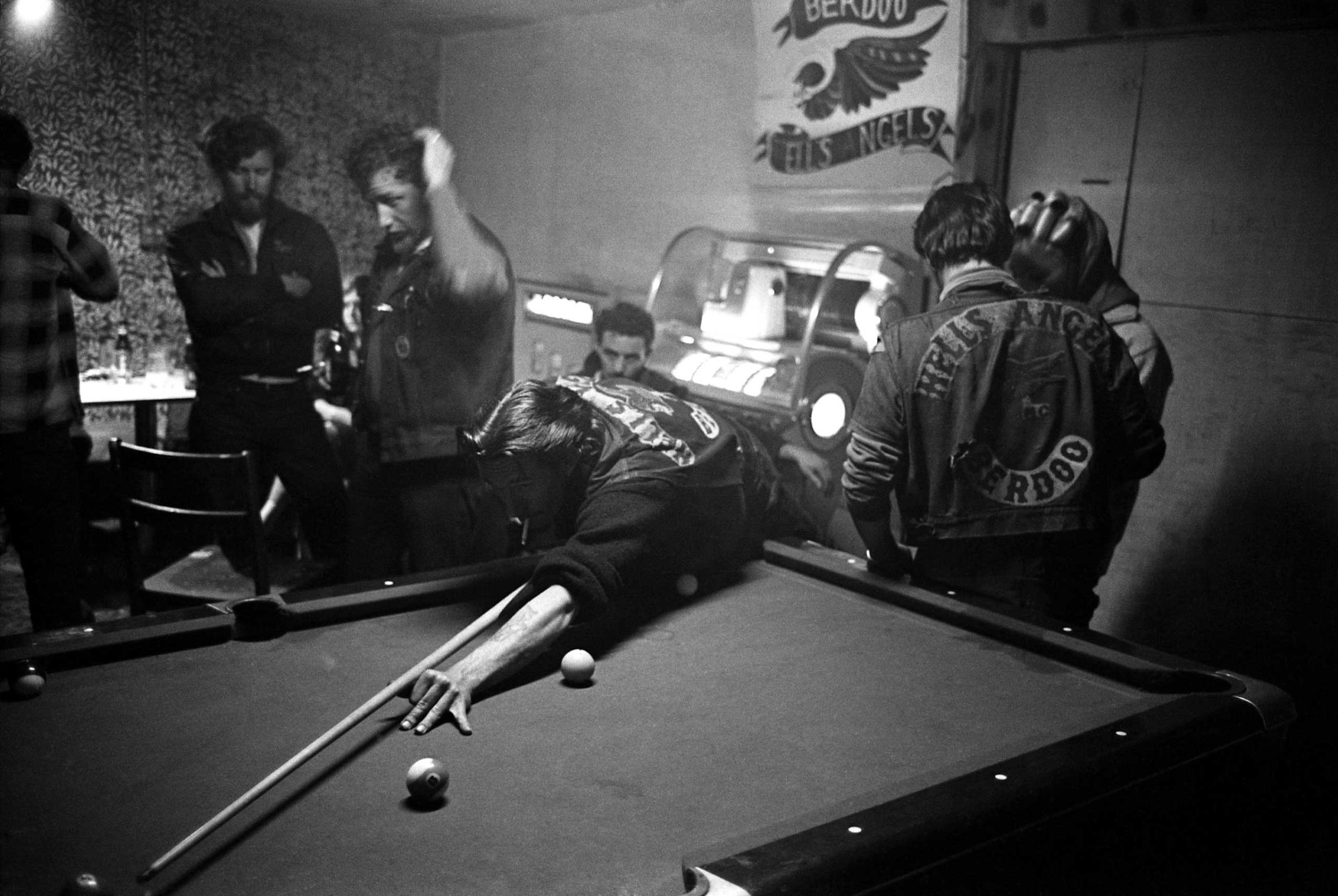

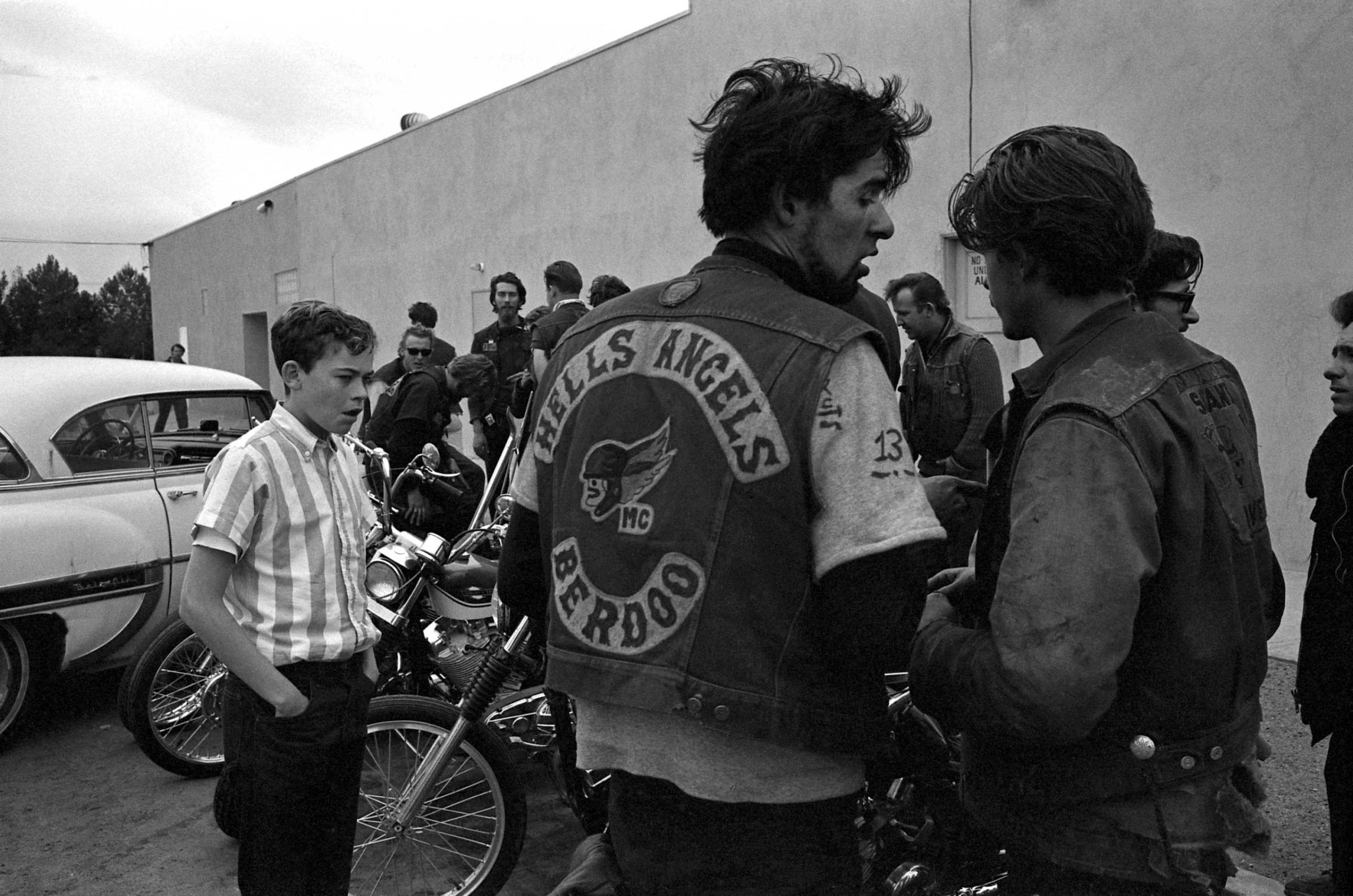

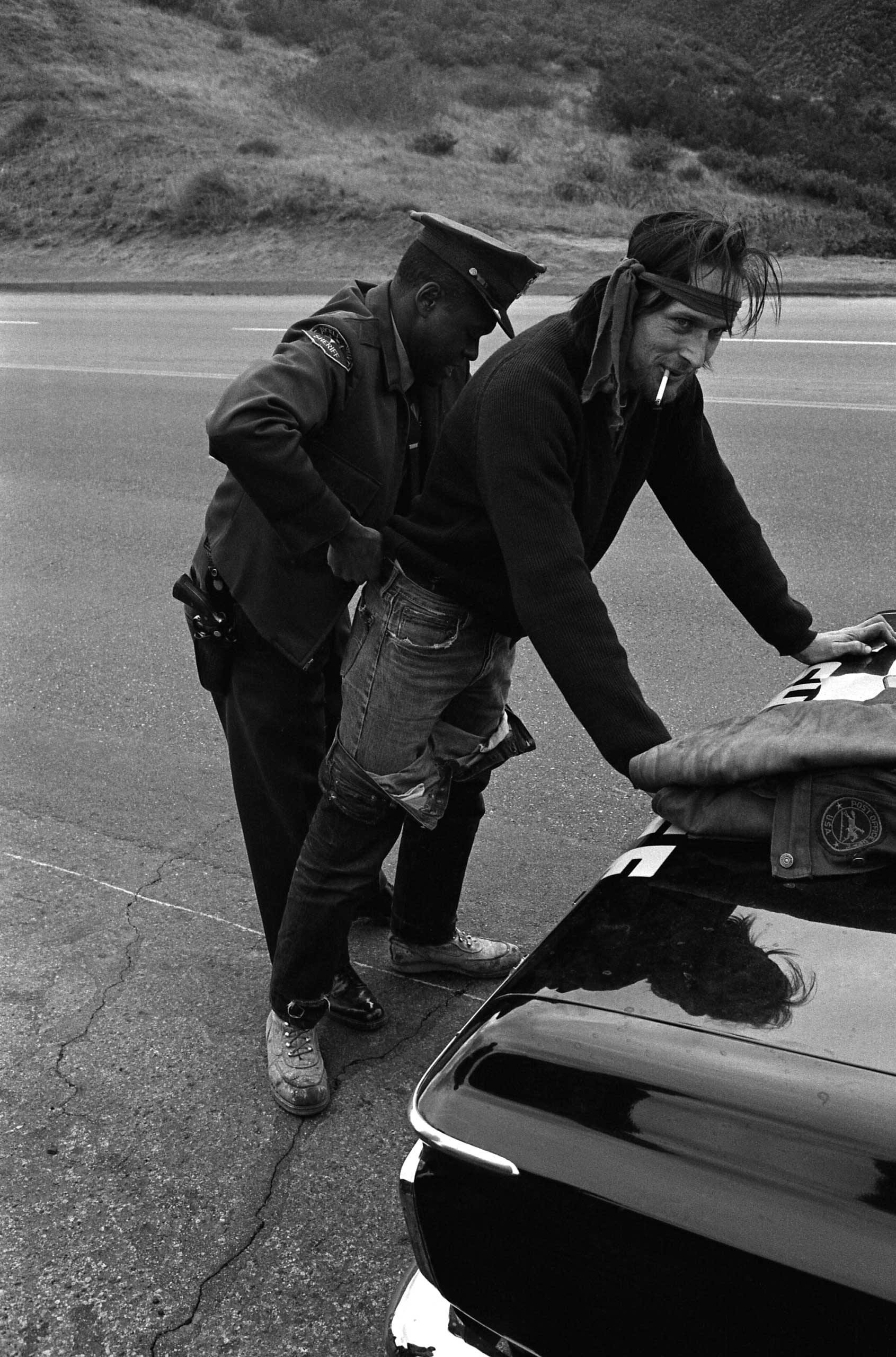

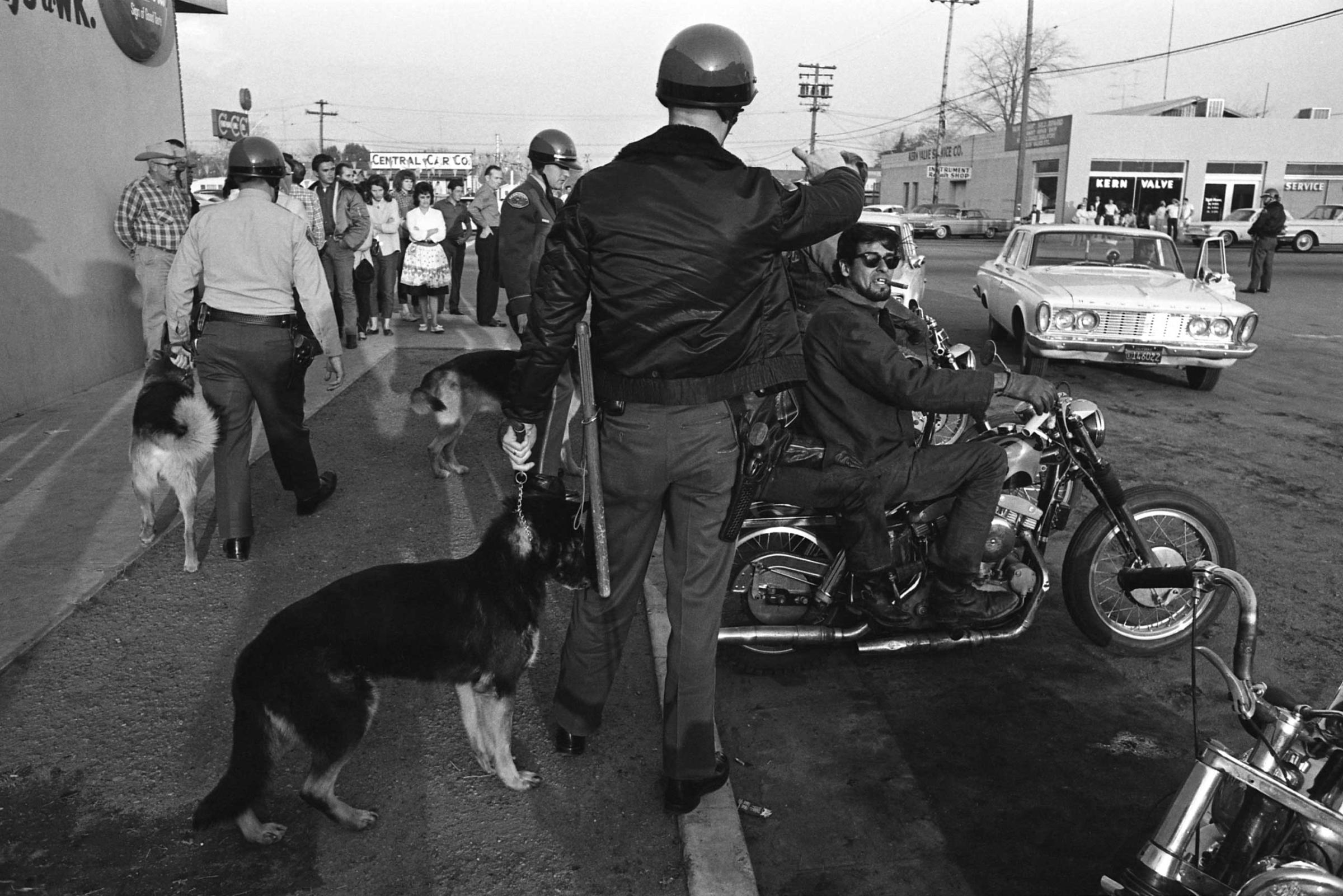

Those clashes only intensified after the founding of the Hell’s Angels around 1950. In 1965, California Attorney General Thomas C. Lynch announced that an investigation of the Angels had found that its 450 members had earned 874 felony arrests between them, that their initiation rite required new members to supply a girl who was willing to sleep with everyone in the club, and that they often ran riot through whole towns, terrorizing residents for fun.

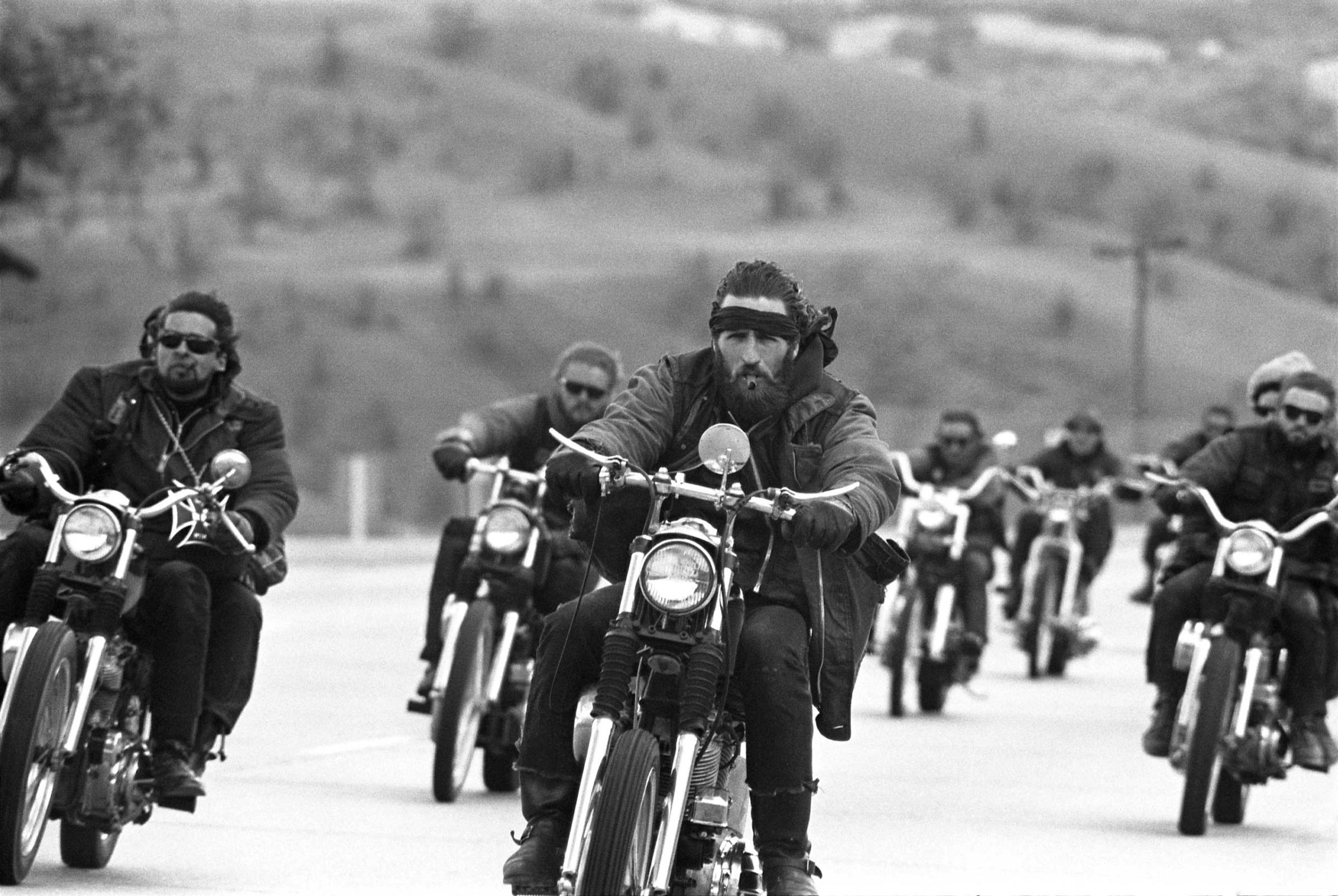

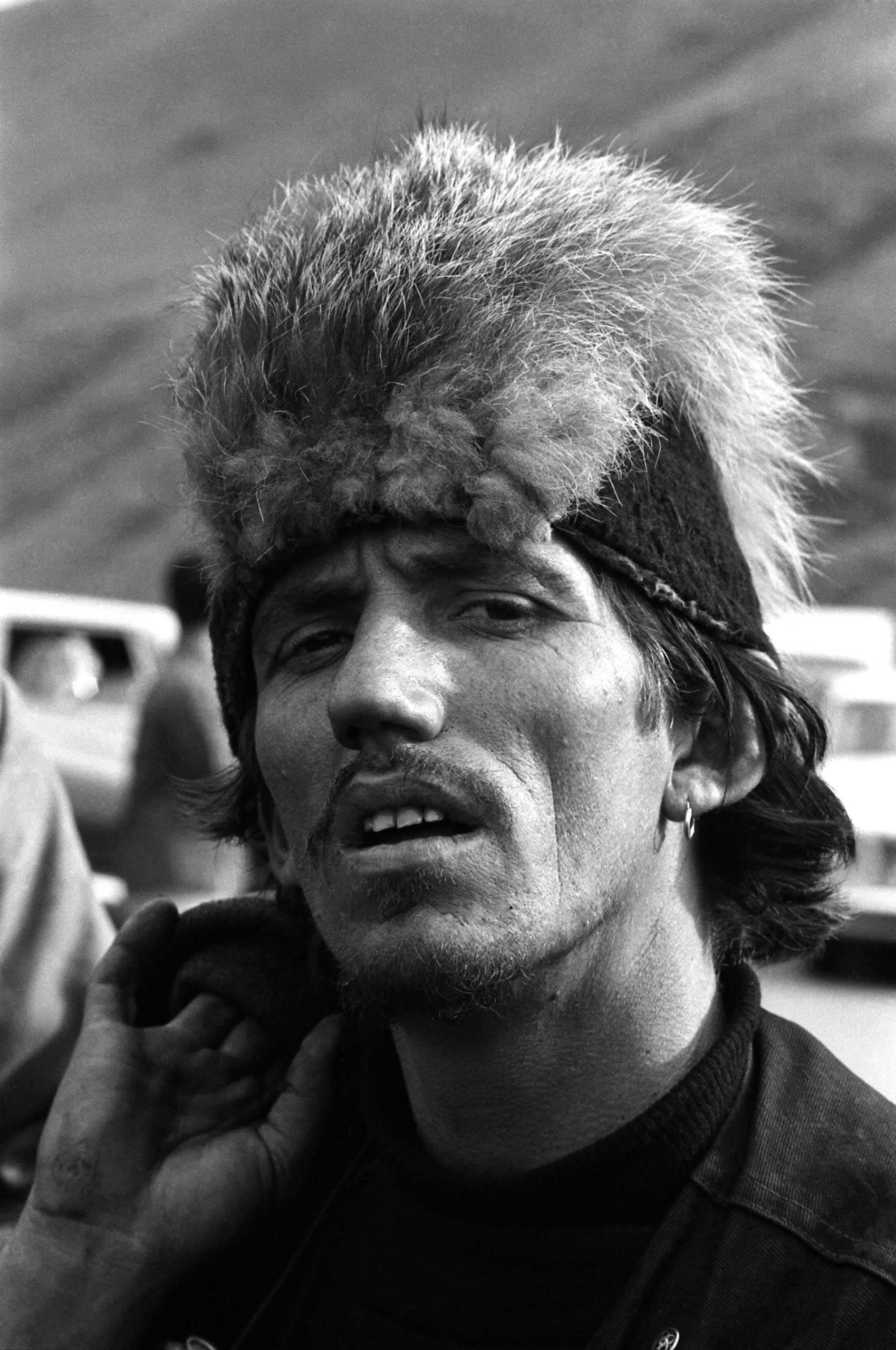

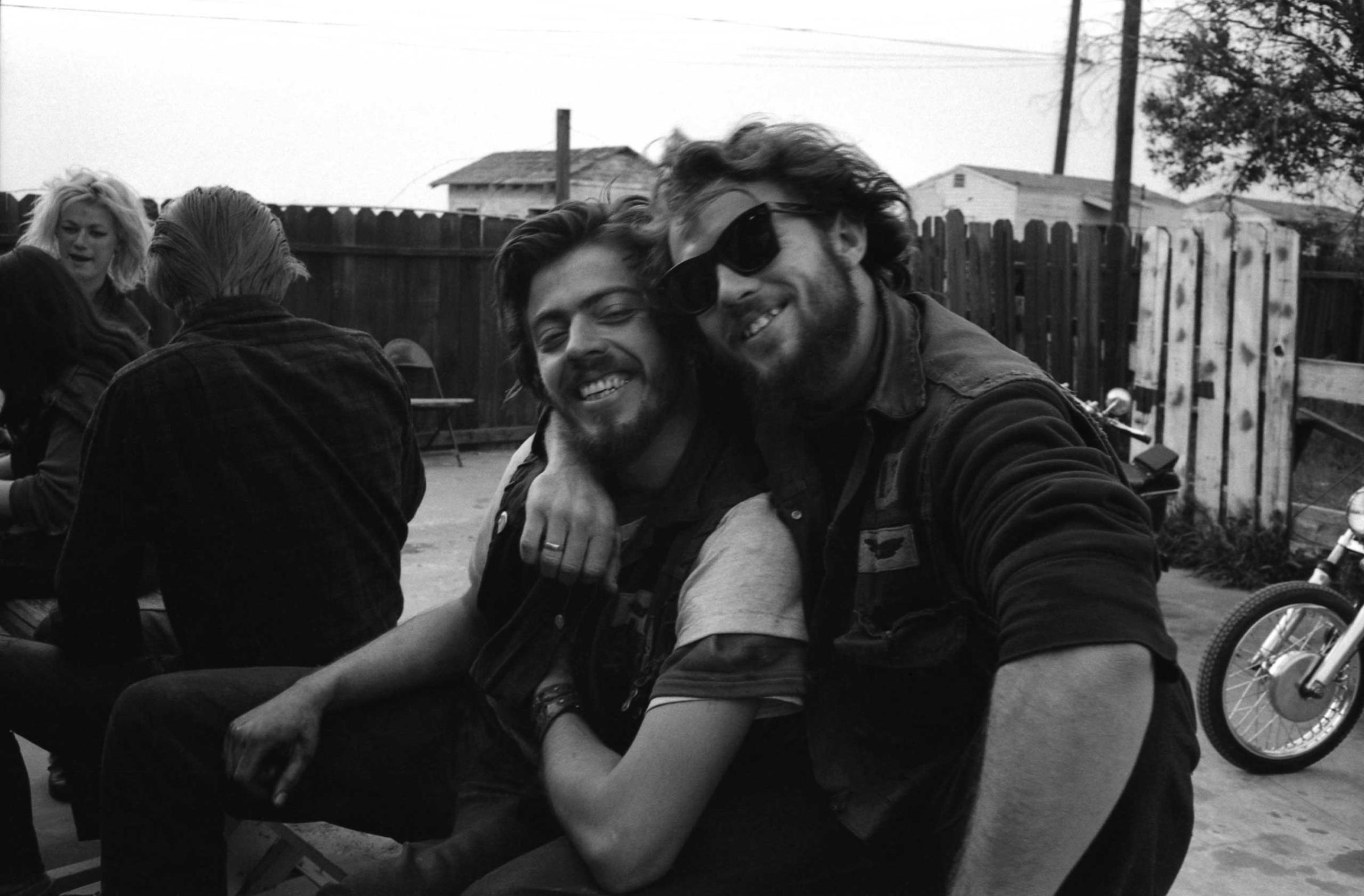

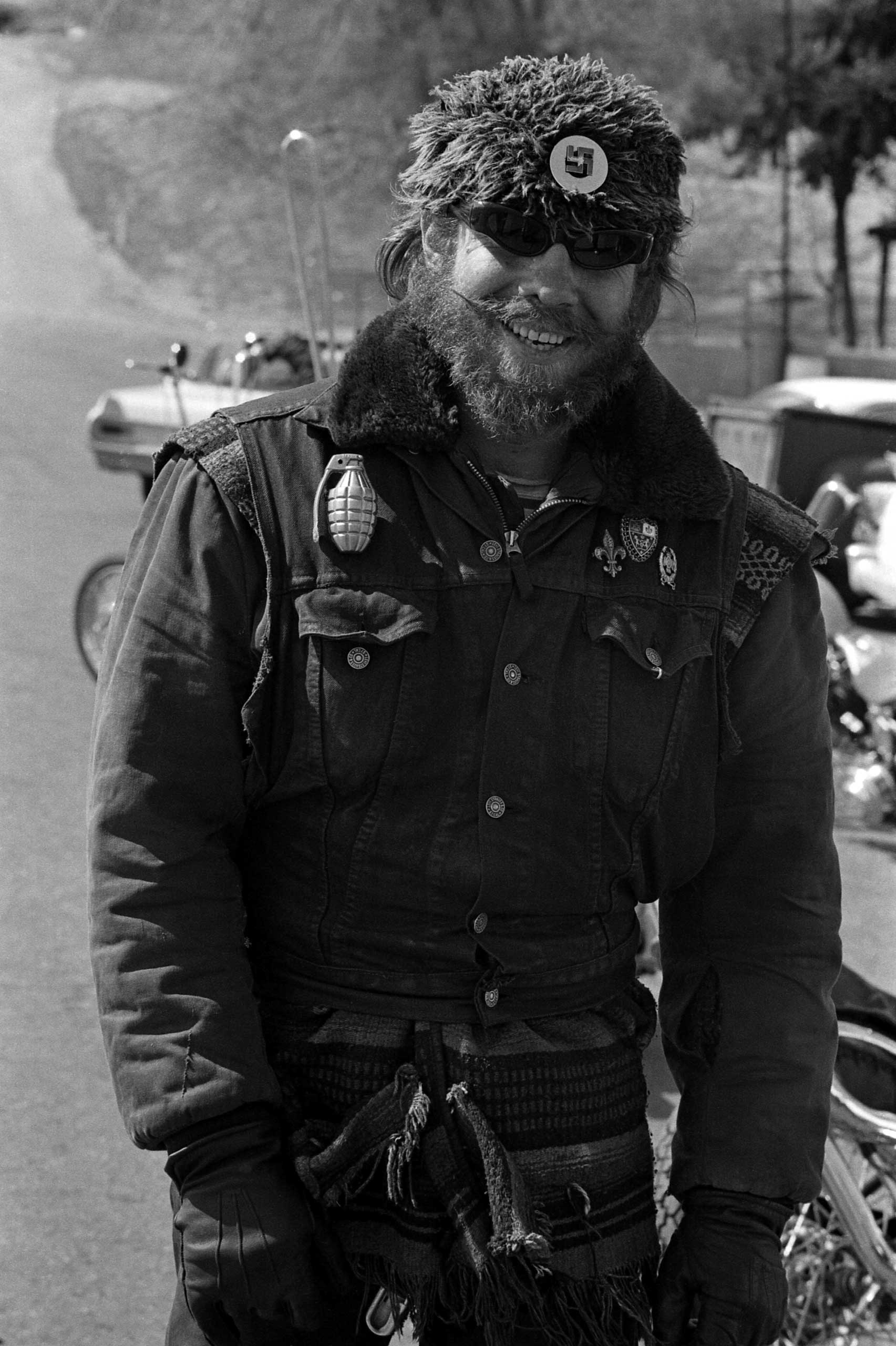

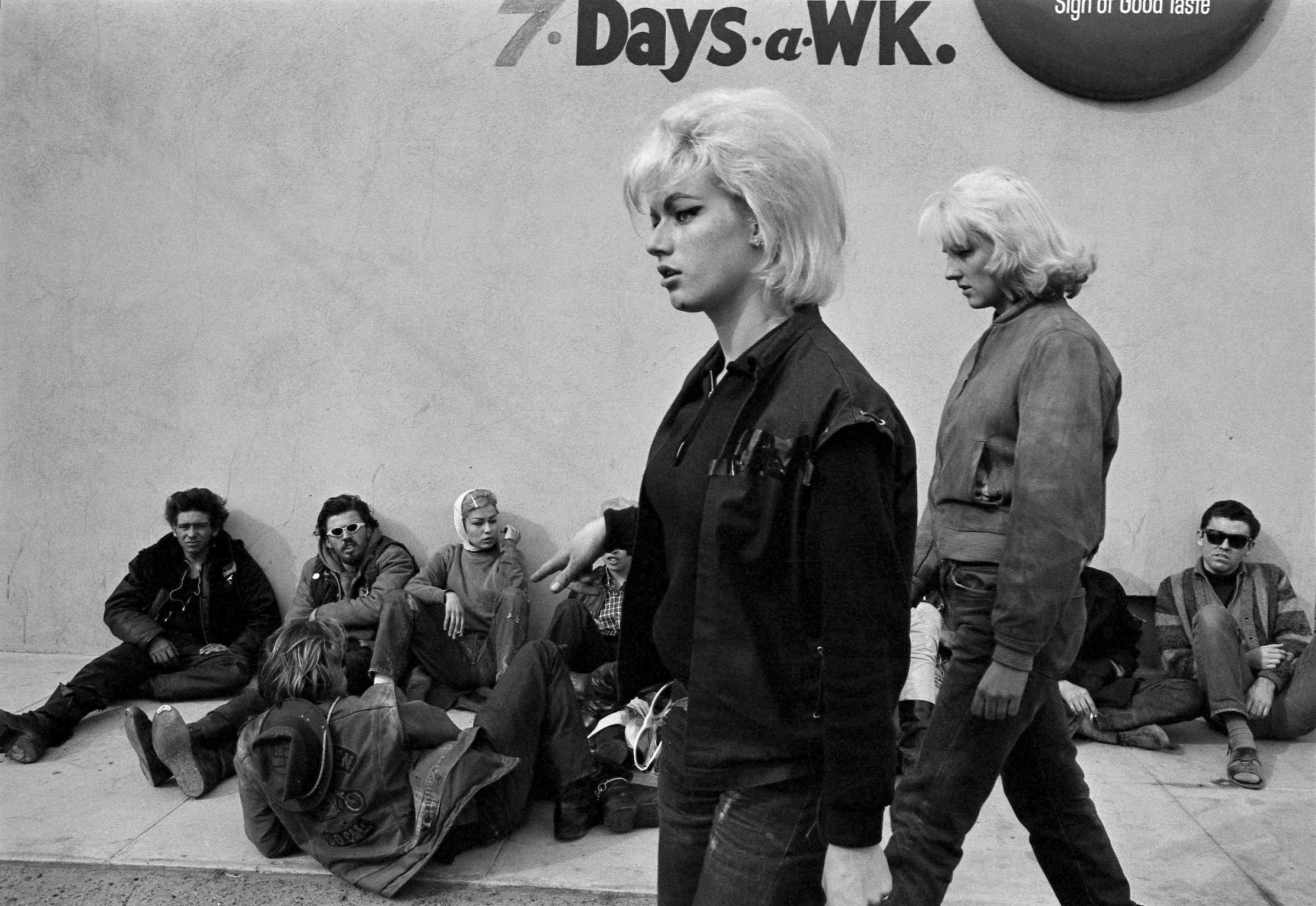

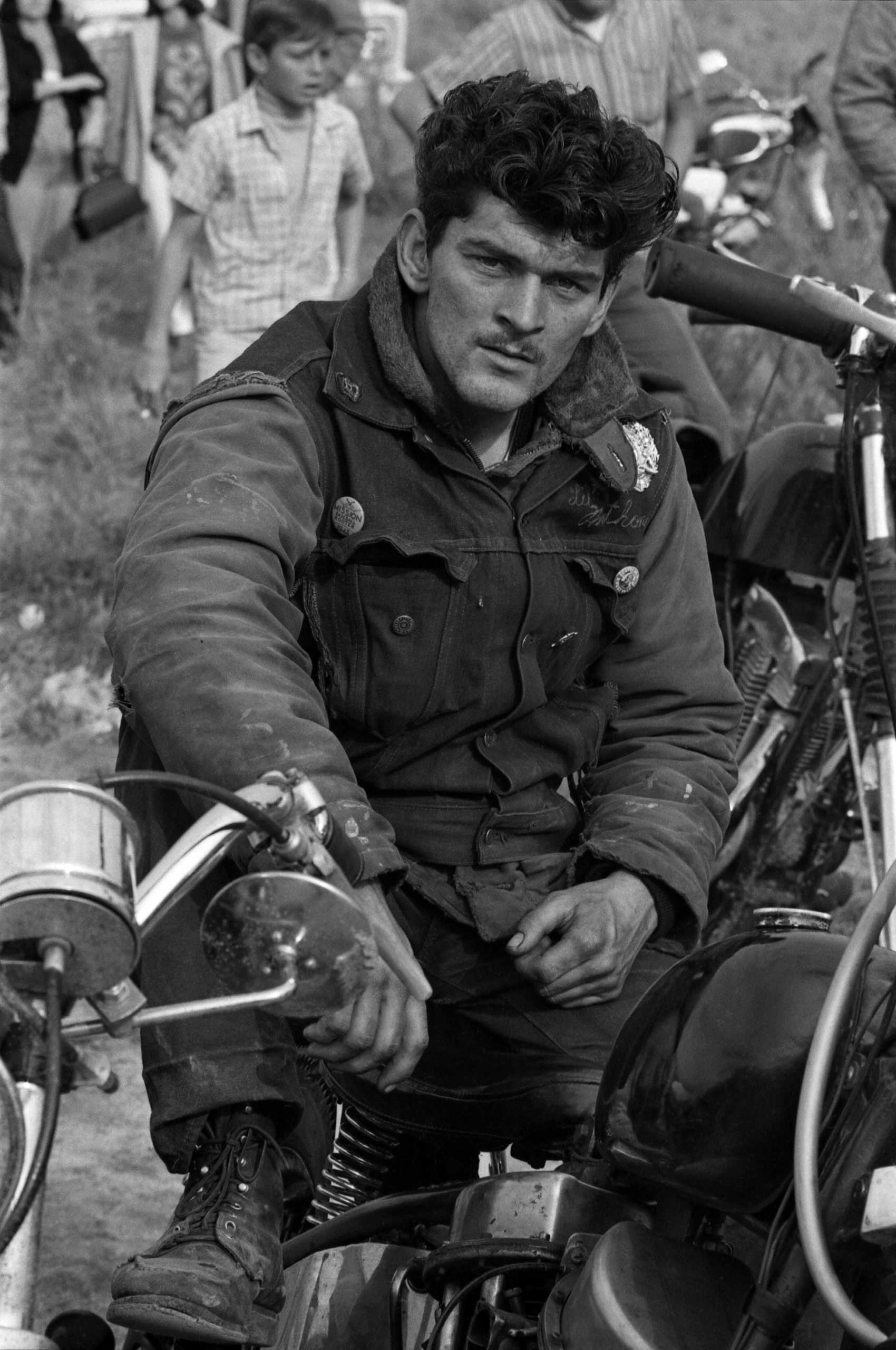

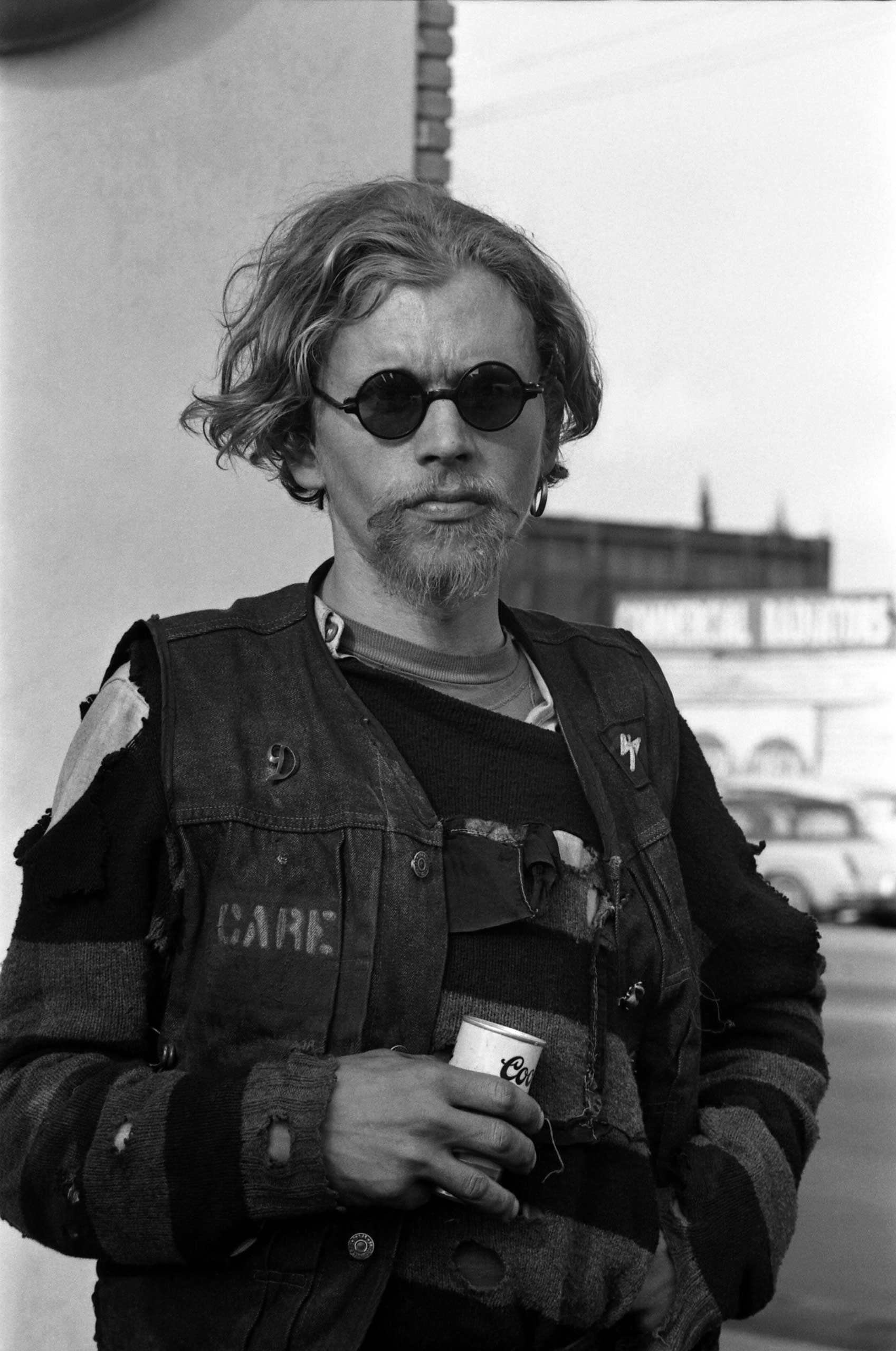

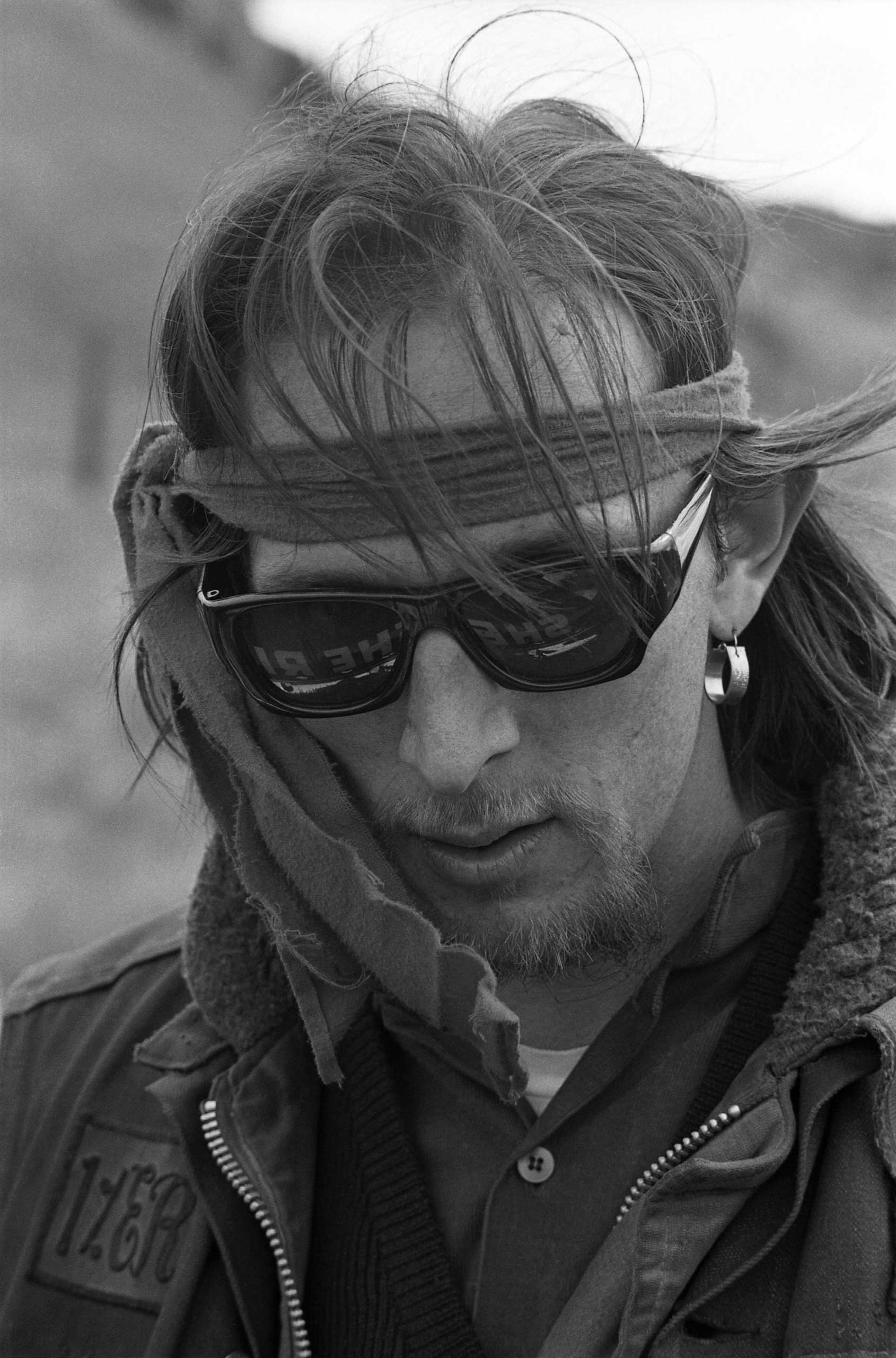

“Guzzling beer and shaking the countryside with obscene laughter, they broke up legitimate motorcycle rallies and often sacked small coastal towns. Perversely, pop music (Black Denim Trousers and Motorcycle Boots) and film (The Wild One) romanticized such outlaw riders as tragic, misunderstood loners, giving the Angels a place that they scarcely deserve in American folklore,” TIME later noted. “As the bike culture burgeoned, the Angels’ legend became as grimy as their beards, Levi’s and leather vests.”

The occasion for that remark was a 1971 knife fight between the Hells Angels and a rival gang called the Breed. It was at the time “the deadliest rumble in the history of maverick motorcycle gangs,” leaving five gang members dead and 21 injured. It was also another example of the tension between legit motorcycle lovers and those outside the law: the location chosen for the brawl was a trade show sponsored by the Cleveland Competition Club, a chartered American Motorcycle Association organization. “[The] annual show is designed to brighten motorcycling’s image, and has never witnessed as much trouble as a fistfight,” TIME wrote. “The proceeds were to go to a crippled children’s fund.”

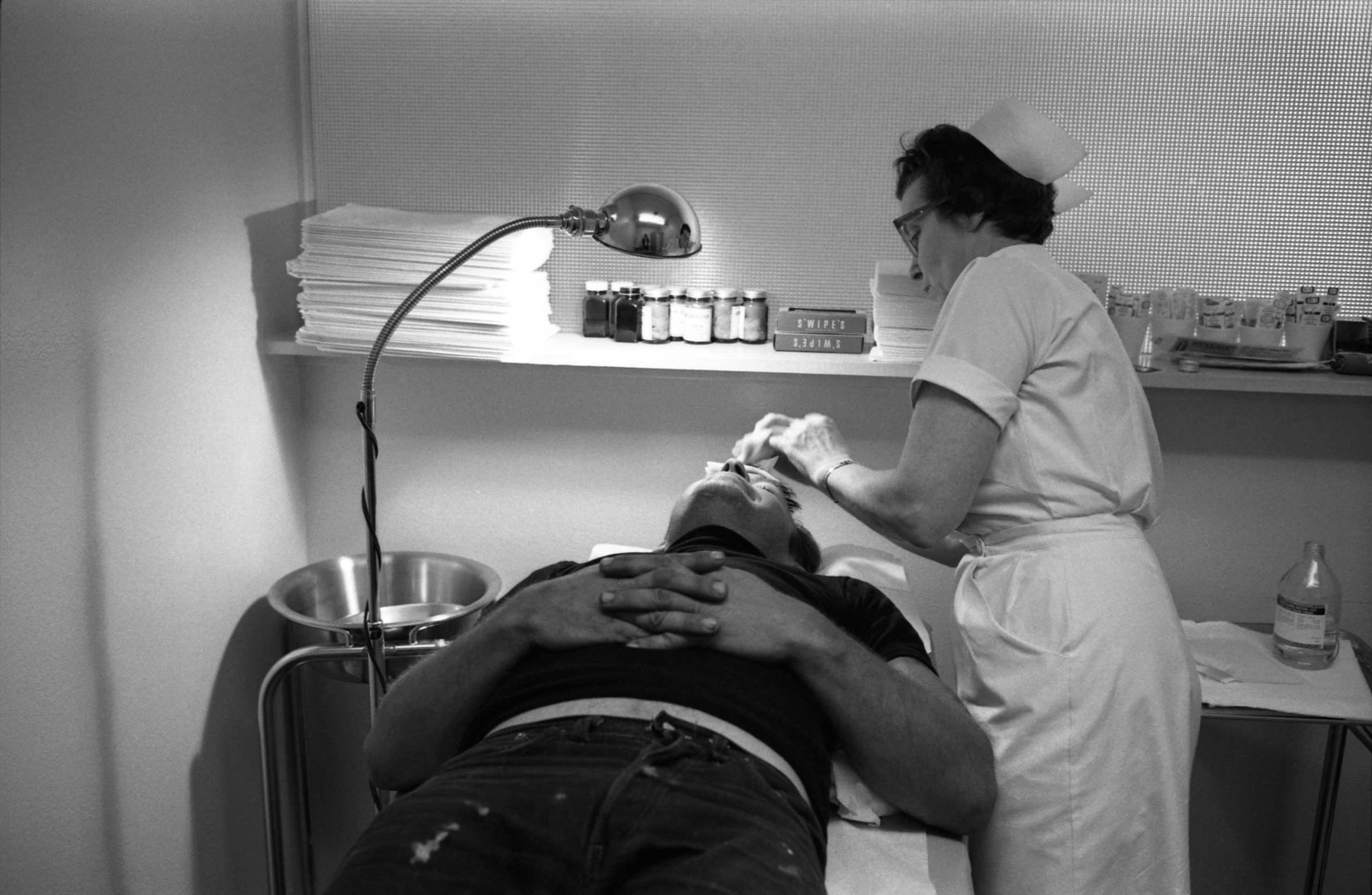

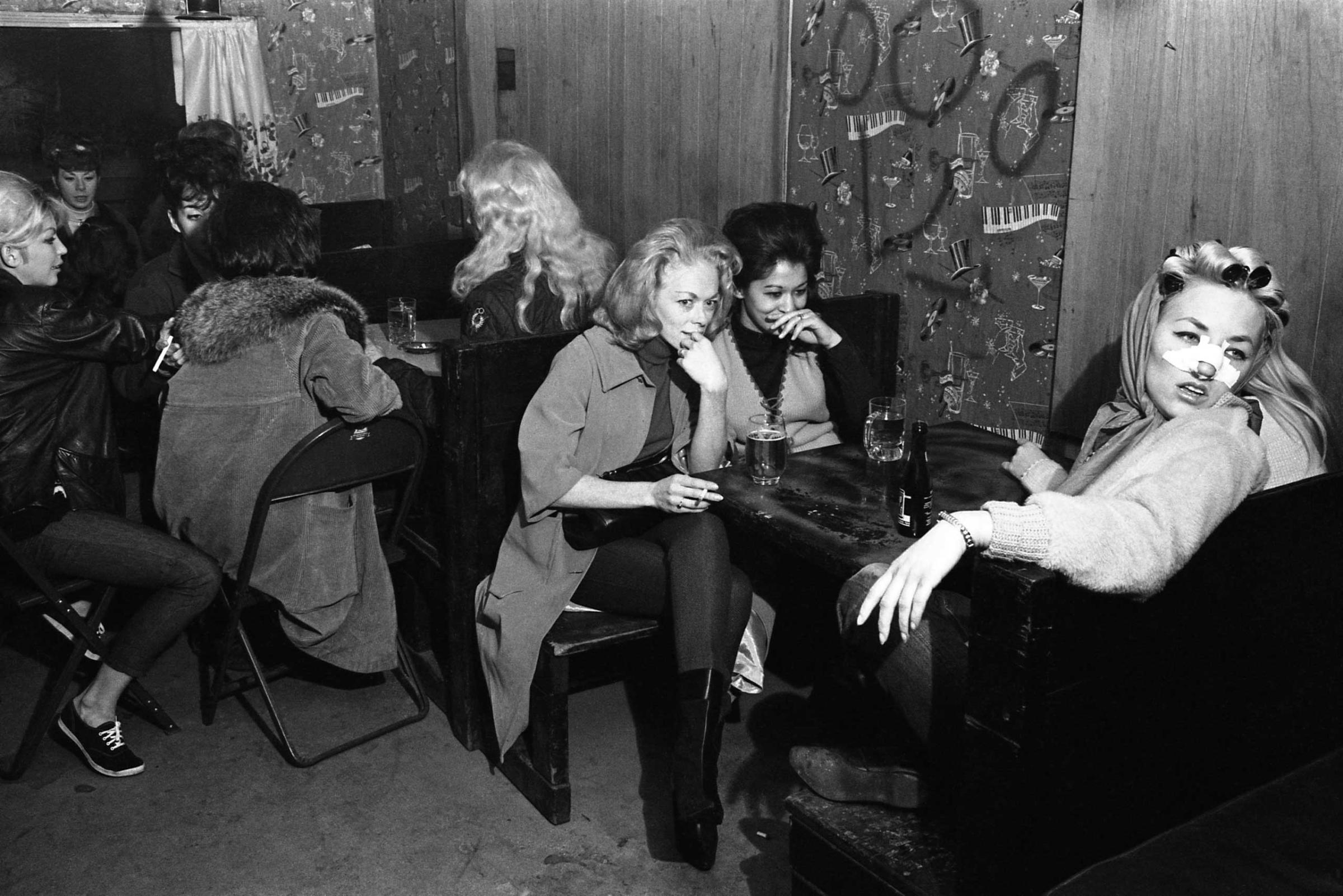

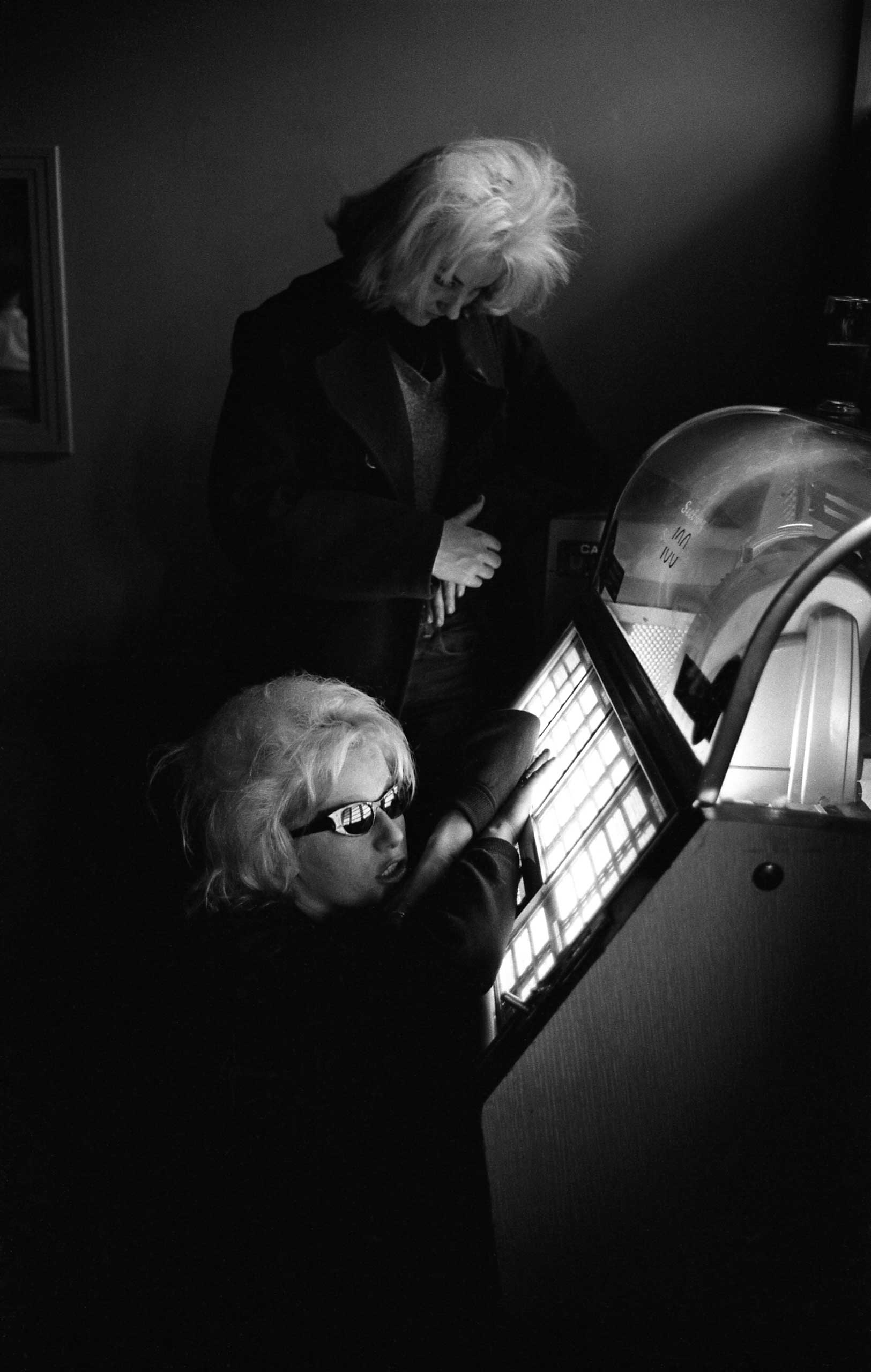

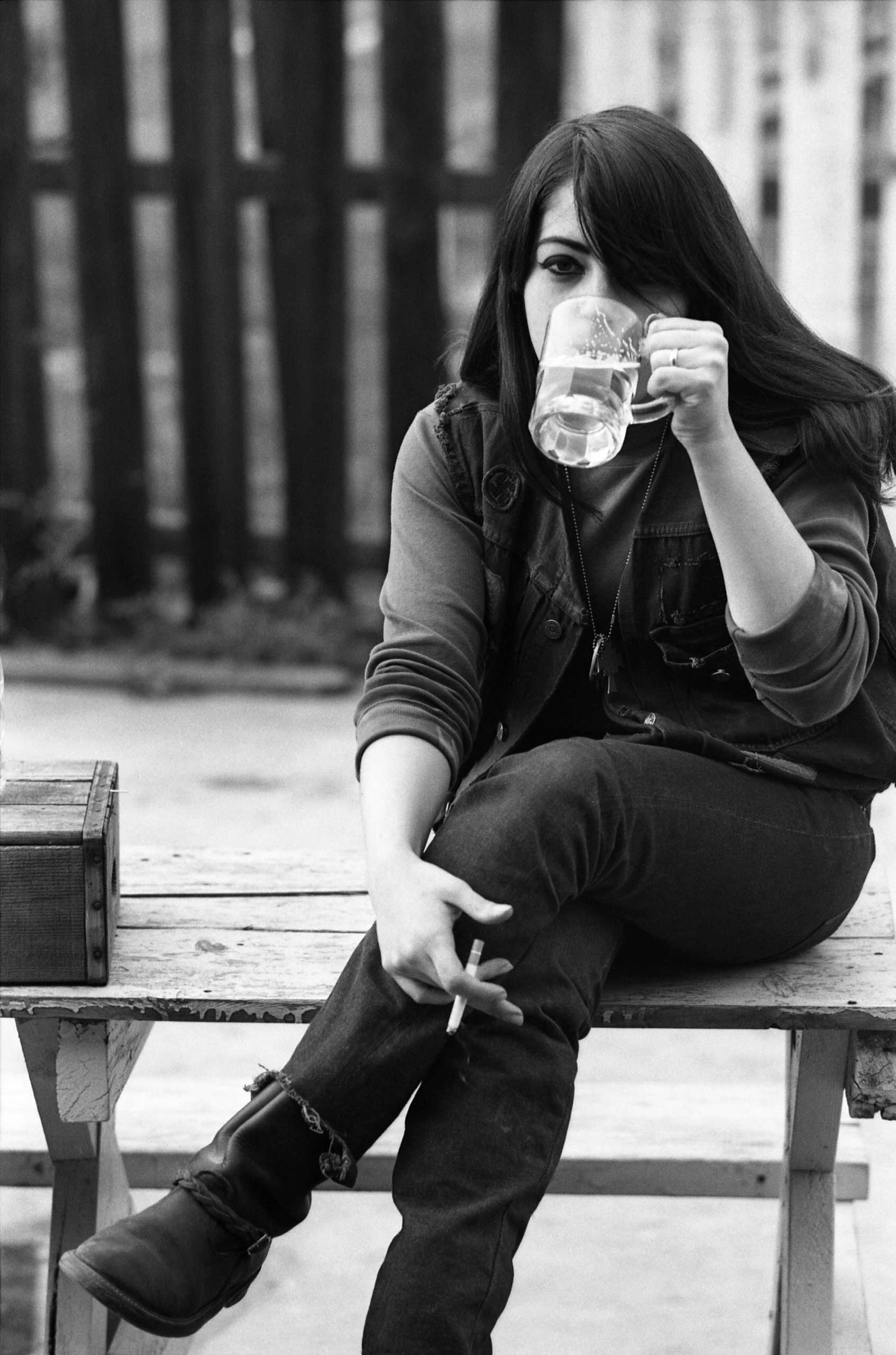

LIFE Rides With Hells Angels, 1965

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com