Despite its name, Mad Men was as much about Madison Avenue’s women as it was about its men. Its name reinforces what these women—women like Peggy Olson (Elisabeth Moss) and Joan Harris (Christina Hendricks)—were up against: a sexist, exclusive boys’ club that forced them to work harder for less pay and a near-daily dose of sexual harassment. Peggy and Joan are well-rounded characters, but they are also case studies in 1960s-era feminism, though they might not have defined their struggles in those terms.

In Sunday night’s season finale, Peggy and Joan both ended up as successful women forging ahead in their industry. But a look at how they got there is an exercise in opposites: Joan strikes out on her own while Peggy works her way up in the corporate machine. Joan chose work over romance whereas Peggy found romance at work. Joan raises her son without a partner, and Peggy gave her baby up for adoption. And Joan has succeeded despite a physical appearance that drew constant unwanted attention, whereas Peggy had to compensate for her plainness in an environment that values beauty.

Serving as a counterpoint to Peggy and Joan, throughout the series, was Betty Draper (January Jones), who, though she was certainly more than a symbol, served as a stand-in for the miserable housewife described in Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique. Showrunner Matthew Weiner read works by Friedan and other feminists while researching the script, and Betty embodied much of the dissatisfaction and entrapment so many housewives felt at the time.

In 1970, when the show ends, women weren’t necessarily discussing work-life balance in the sense of “having it all,” as the conversation sometimes goes today. But applying that framework, anachronistically, to the lives of Mad Men’s leading ladies yields some noteworthy insights. If “having it all” can be defined as balancing a fulfilling career and personal life, then Peggy, Joan and Betty draw sticks of varying lengths.

Betty, of course, draws the shortest by far—terminal lung cancer—and just as she was finding her calling. Joan draws longer, but not as long as she would have hoped. She gets the fulfilling career but at the price of losing a would-be fiancé, and she’s stuck in a role—motherhood—which she struggles to fully embrace. Peggy, however, seems to get as close to “it all” as any woman on the show, finding both love, in the form of Stan Rizzo (which some would argue was a rom-com cop-out), and a promising career at McCann Erickson.

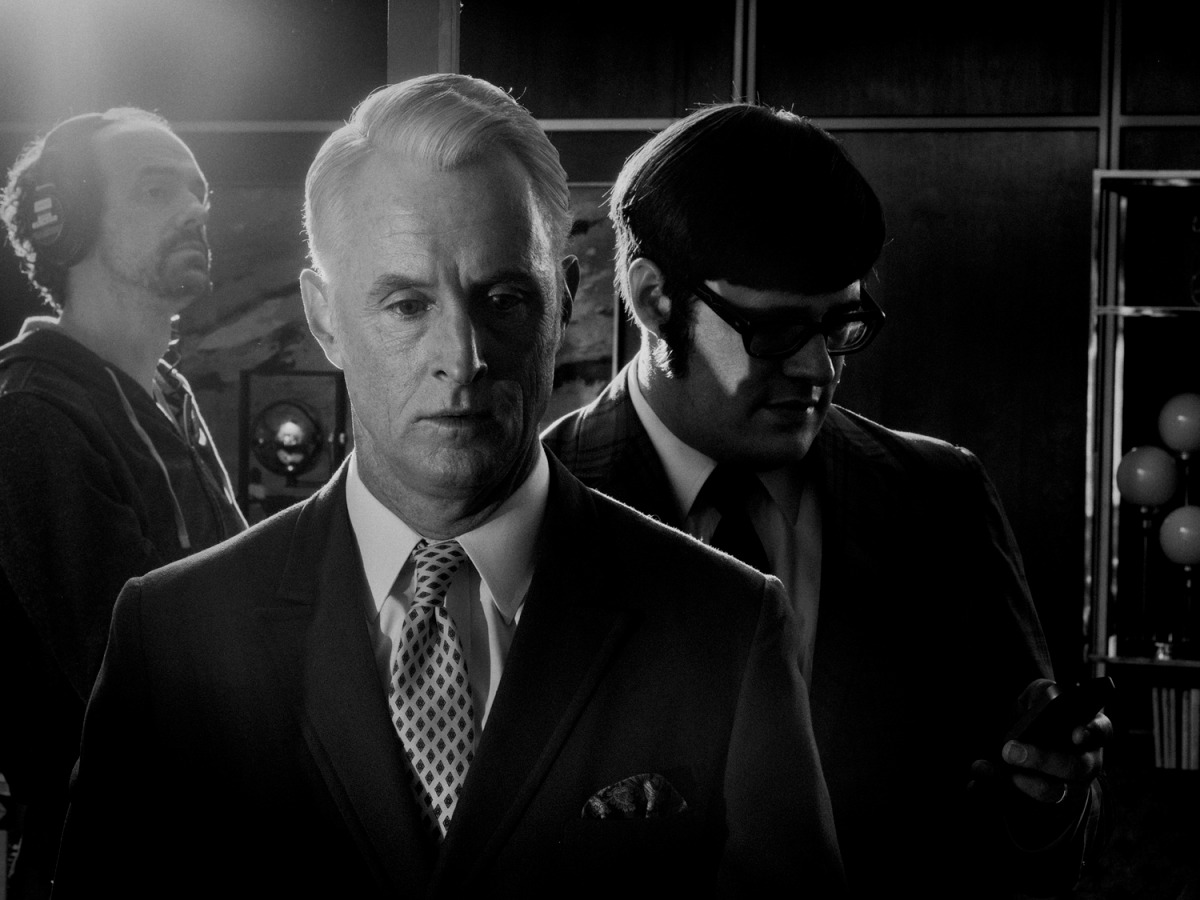

'Mad Men' Up Close: Photos From the Set of the Celebrated Show

Is it a coincidence that Betty, of the shortest stick, holds the most regressive ideas about women? That Joan, who’s relied, at least in part, on the advice she gave Peggy on the latter’s first day—go home, put a bag over your head and be honest with yourself about what needs improvement (to paraphrase)—gets only a portion of “it all”? And that Peggy, who has always relied on her intellect above her appearance, gets the most robust version of a happy ending? On a show on which even the apples and bananas in the Drapers’ kitchen are deliberately small—because these were the pre-GMO days—it would seem that nothing is a coincidence.

Of course, Mad Men‘s writers are presumably more sophisticated than doling out fate based on characters’ adherence to modern-day feminist values. It’s an unfair measuring stick with which to play God. But if they were, beneath the narrative, hoping to send a subtextual message to viewers about how women today should be valued and appreciated, this would be one way to do it.

The feminist struggle on Mad Men was often an implicit one, explored less in terms of outspoken ideology than in terms of the daily struggle to move forward in the workplace while possessing lady parts. Though Joan and Peggy proved that this struggle could be expressed in wildly different ways—and finally put their differences behind them in a satisfying win for female solidarity—the juxtaposition of their characters was also limited in an important way: They are both white women.

Second-wave feminism, a movement which Peggy and Joan never explicitly claimed but which rose to prominence during the era of Mad Men, was widely criticized for its exclusion of non-white women. The characters of Dawn (Teyonah Parris) and Shirley (Sola Bamis), two black secretaries with more minor roles on the show, offered an opportunity to explore the richer territory of the racial divisions within feminism during the 1960s.

Dawn and Shirley face racism in the office, both overt and subtle, in addition the sexism Peggy and Joan face. But the decision not to feature their stories more prominently—or, more likely, the lack of a proactive decision to feature them—was a missed opportunity for a fuller examination of women at work in the ‘60s.

Though Weiner has said there will be no spin-offs, many seem to be holding out hope that we have not seen the last of Dawn and Shirley. And in the absence of a spin-off, we can only hope that the fictional Dawn and Shirley found the same satisfaction that Joan and Peggy did. Shirley, we know, bid adieu to advertising for good. As she told Roger on her way out of the office, “Advertising is not a very comfortable place for everyone.” Joan and Peggy would certainly have agreed, though they would not have fully understood.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com