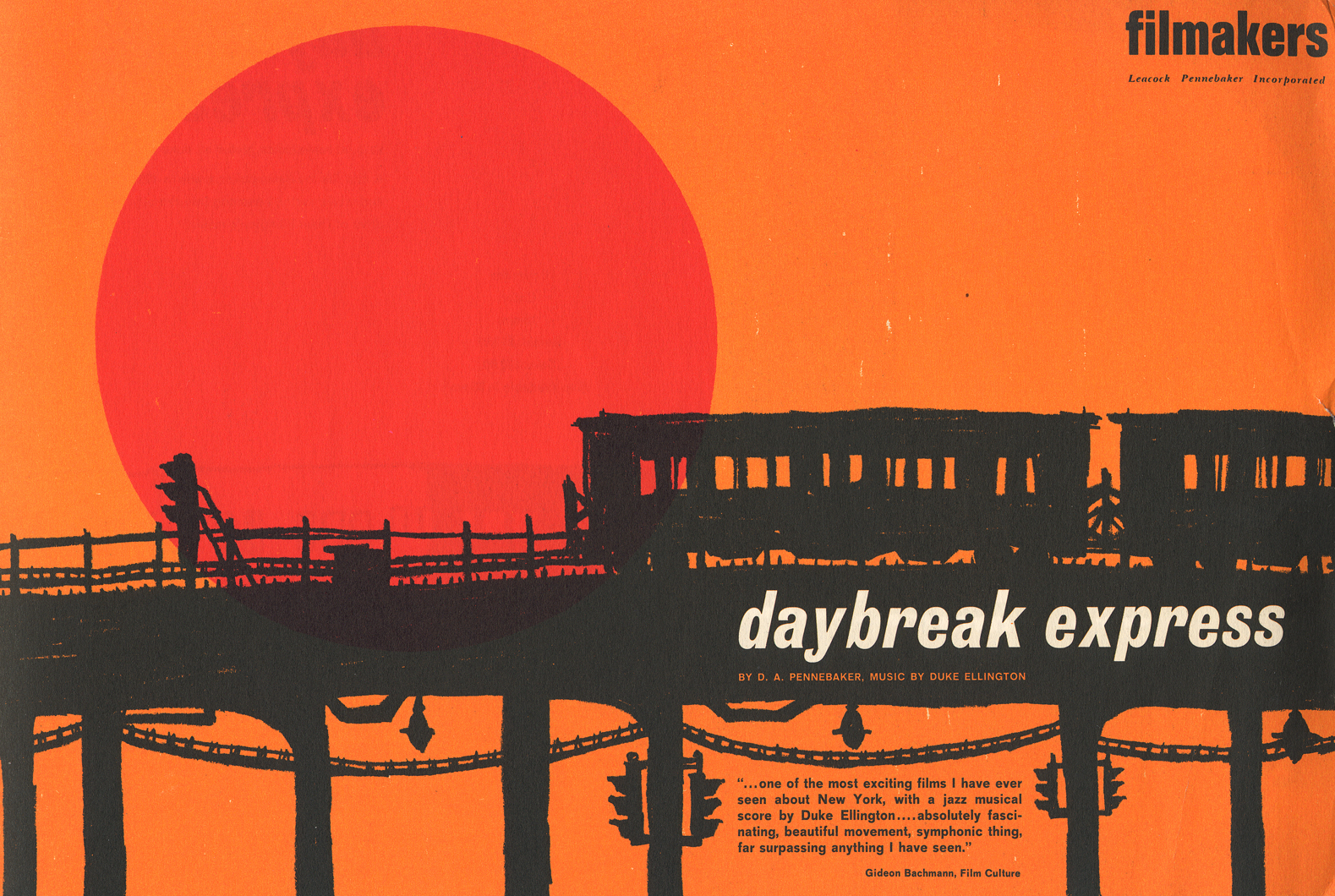

In 1953, Donn Alan “D. A.” Pennebaker produced and directed his first film, Daybreak Express, a vivid, dizzying tribute to New York City’s elevated subways. The film pays tribute to a day in the life of a bustling city, but omits any traditional narration in favor of a stirring soundtrack by Duke Ellington. As the sun rises and sets on subway cars and city buildings, Pennebaker’s camera chugs along at a perfect pace with the music. Clocking in at just over 5 minutes long, the film packs the energy of a full day into a series of straightforward observations and disorienting abstractions, without ever missing a beat.

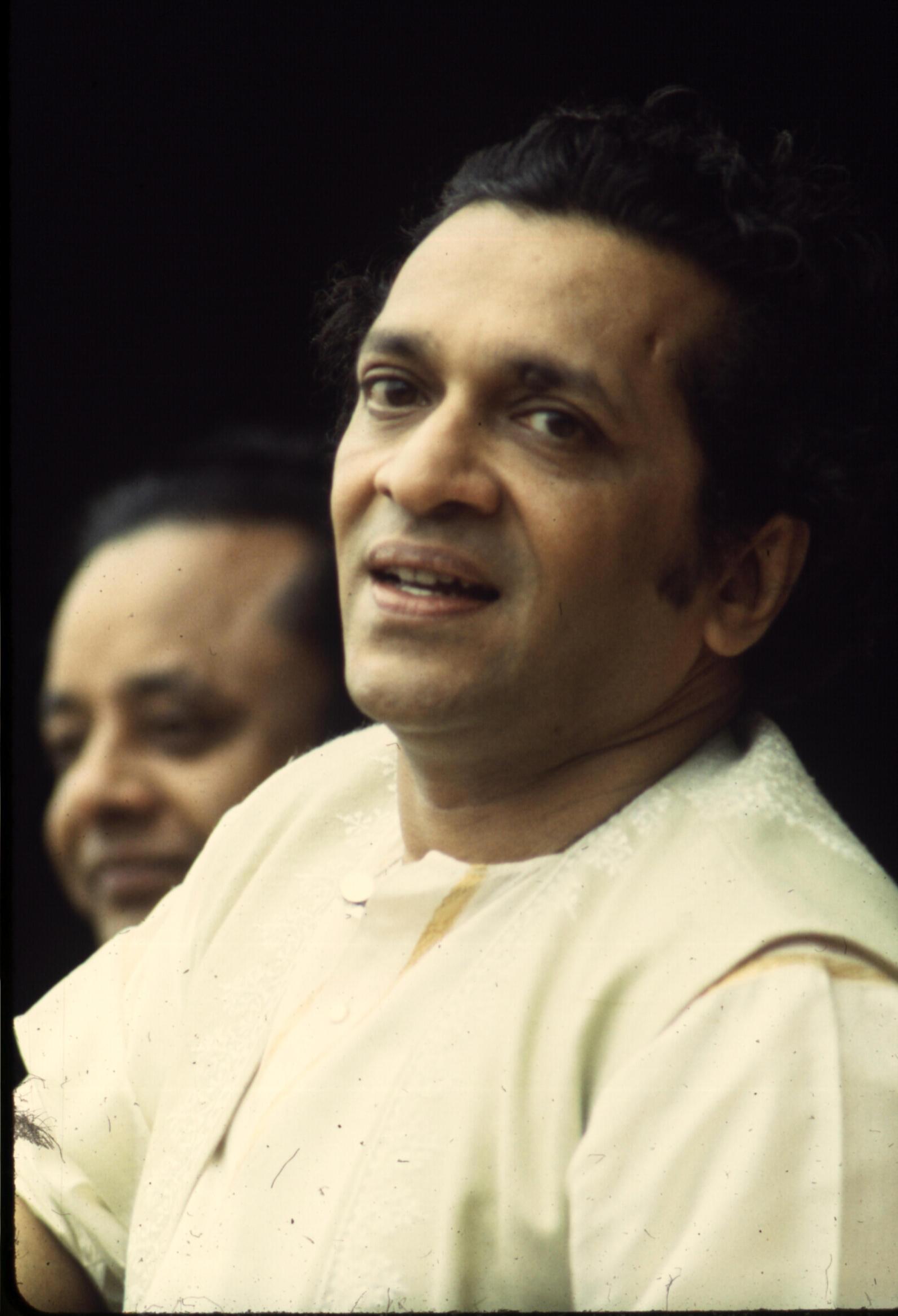

Having cast off his early ambitions to become an engineer, Pennebaker set out on his own, seeking like-minded and entrepreneurial individuals to join him on a quest to create artful films that nevertheless captured reality. His search would eventually lead him not only to his wife and filmmaking partner, Chris Hegedus, but to a cast of characters who would go on to change the very nature of documentary storytelling.

In the years after Daybreak Express, Pennebaker continued crafting on-the-fly films that followed real people through their daily lives. In 1954, his attempt to film his toddler during a day at the zoo turned into a rollicking chase through Central Park that became the black-and-white short film Baby, a film he said forced him to let go of any narrative structure he might have had, and let the subject dictate where the film was going. In 1959 he filmed Opening in Moscow, a Kodachrome exploration of an America-centric Russian trade fair that also marked his first collaboration with legendary filmmaker Albert Maysles.

“In Russia, we would go out to the countryside, away from Moscow, and try to film the locals,” Pennebaker recently told LIFE.com “But the problem was, we couldn’t do dialog. I saw what we were doing as a kind of theater, and you need dialog for theater. So the idea of getting dialog into these films became very important. We needed sound, but there were no cameras that could do it. Sync cameras were around, but they were heavy and you had to use them in a studio. We wanted something that we could bring anywhere, and that required machinery that didn’t yet exist.”

Pennebaker and his colleagues would go on to develop a lightweight, portable, sync-sound camera with financial support from LIFE magazine and the visionary leadership of Robert Drew, a writer and editor who was pushing the weekly magazine to approach journalistic filmmaking with the same care and attention it paid to documentary photography. Drew’s work with LIFE, and later with his own production company, Drew Associates, effectively laid the groundwork for the cinéma vérité movement in America.

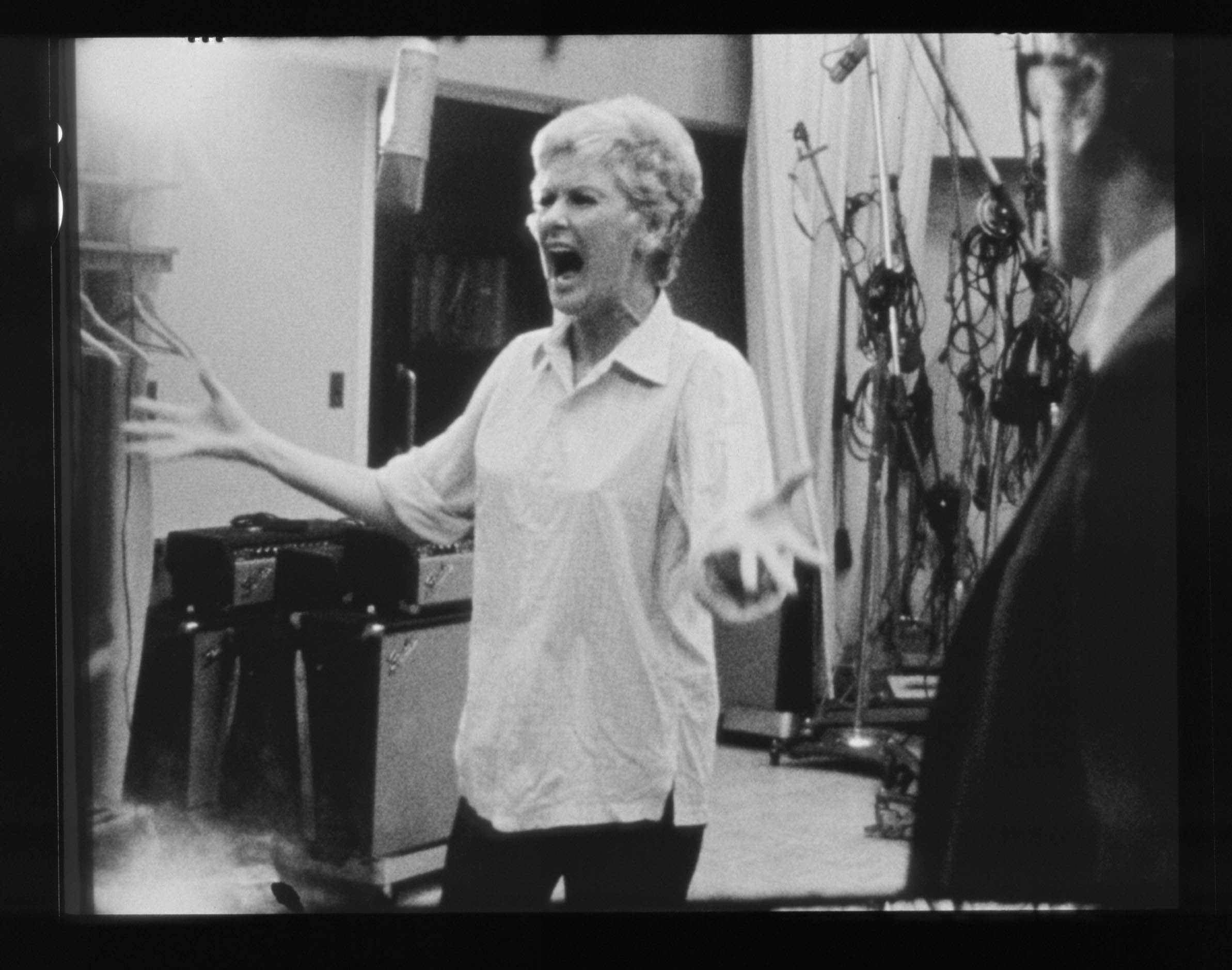

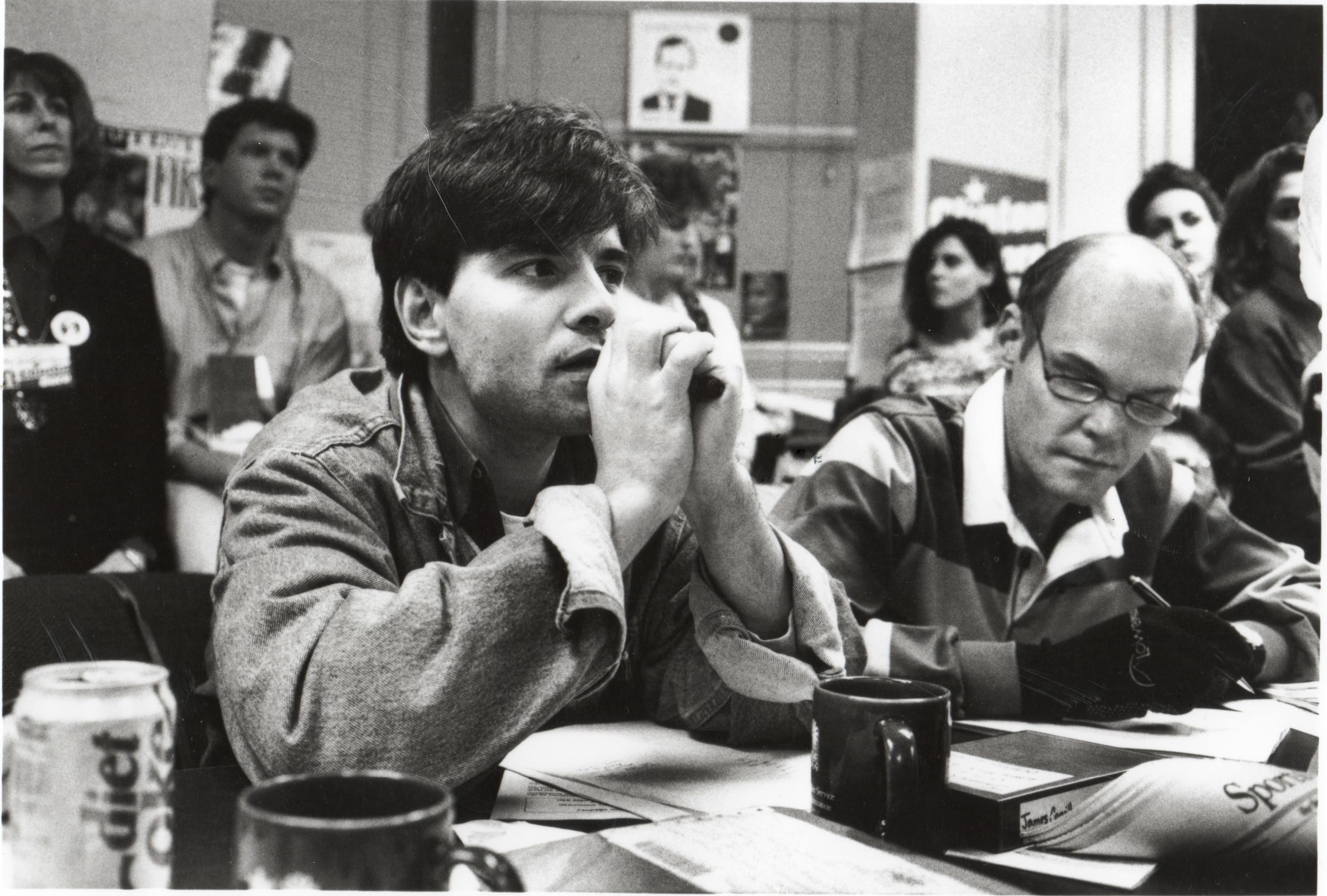

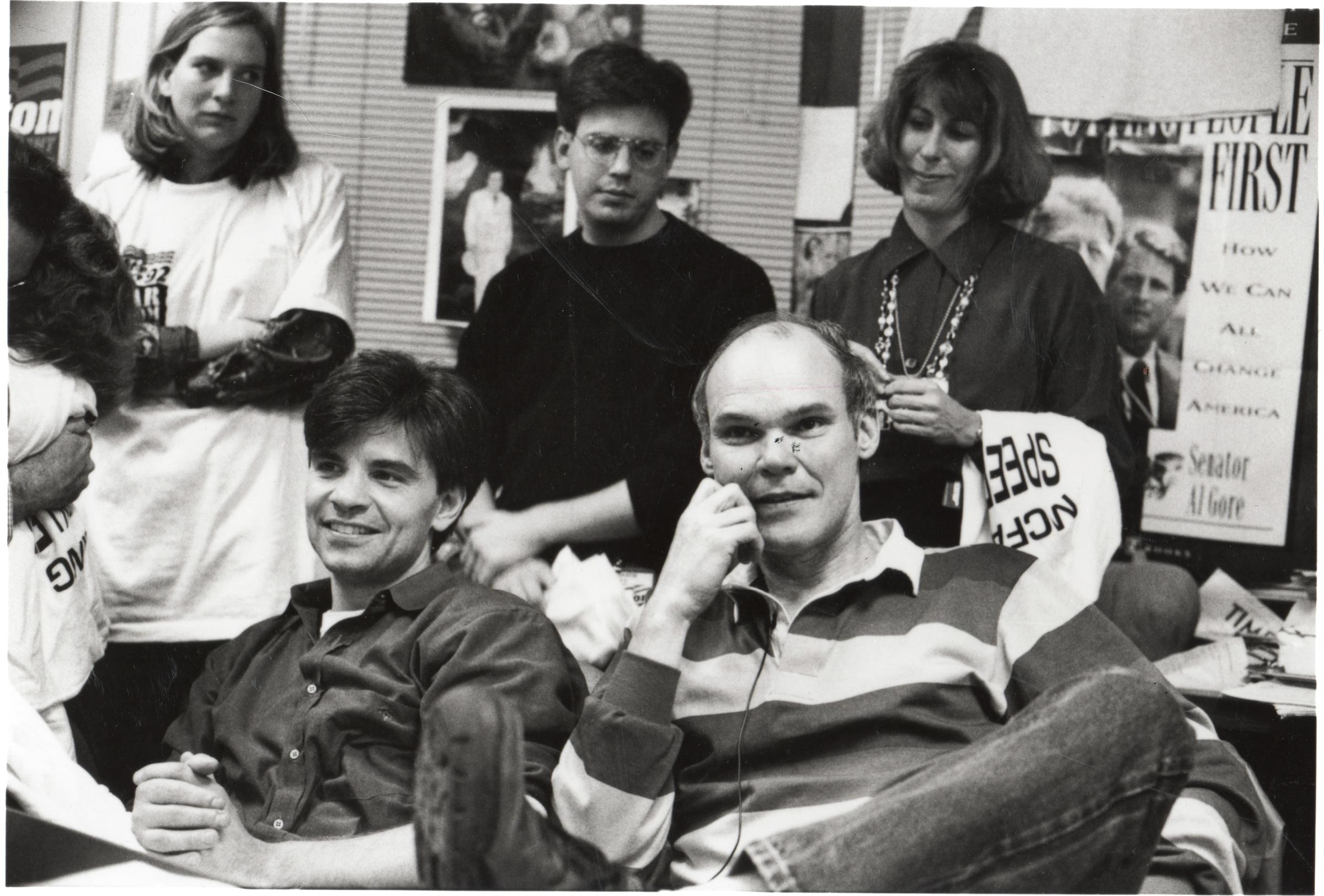

“There was a lot of excitement when these films first appeared,” Chris Hegedus recalls. “No one had followed real-life stories in that way before, and they really were trying to do something that LIFE magazine had started to initiate with its photojournalism, and take it a step further. I remember when I saw the first vérité films, I was given the feeling of really being there, and that had to do with both the picture and the sound. Since then, we’ve looked for stories like that, following people who are passionate about something in their lives and are taking some kind of risk, and we somehow convince them to bring us along on their journey.”

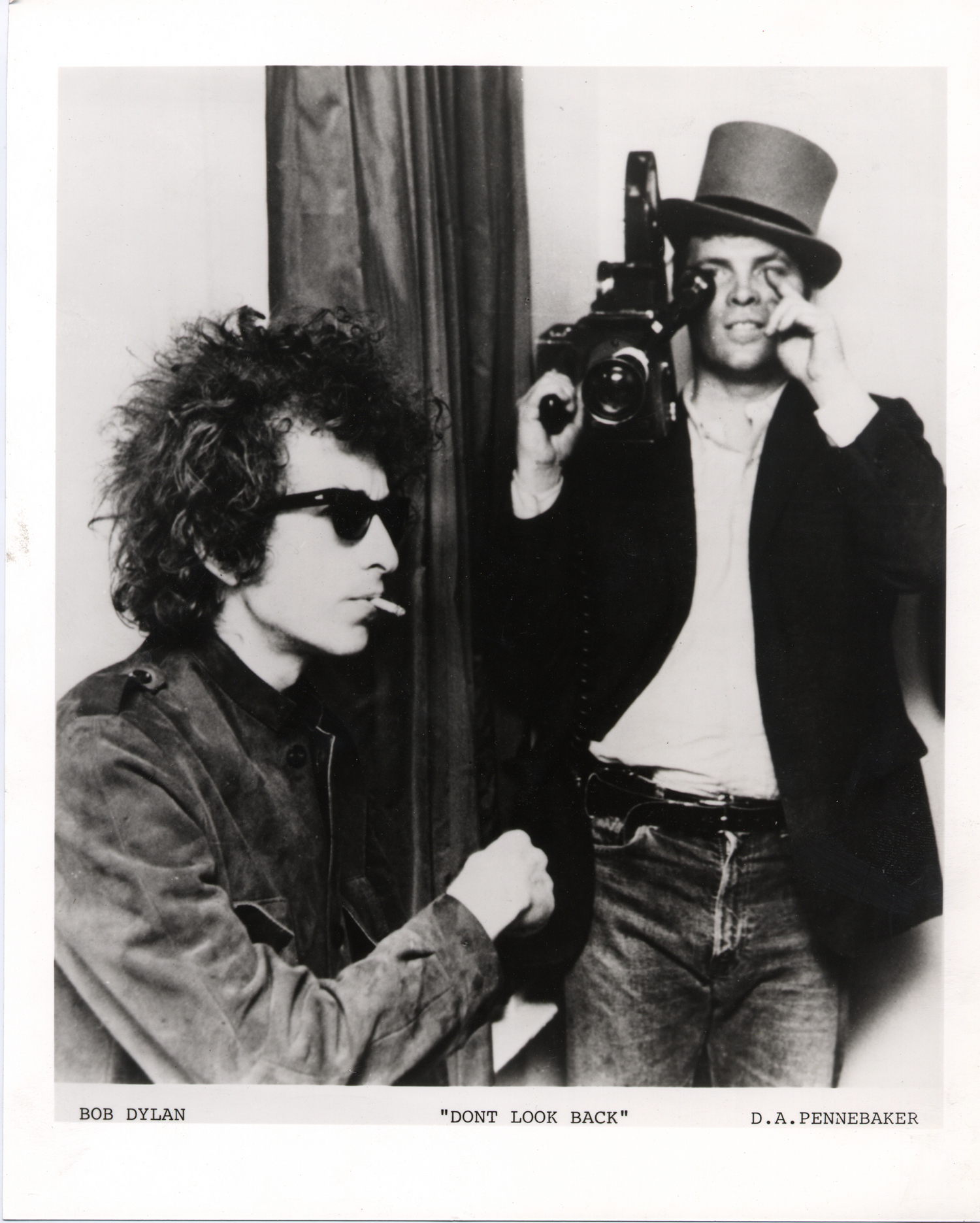

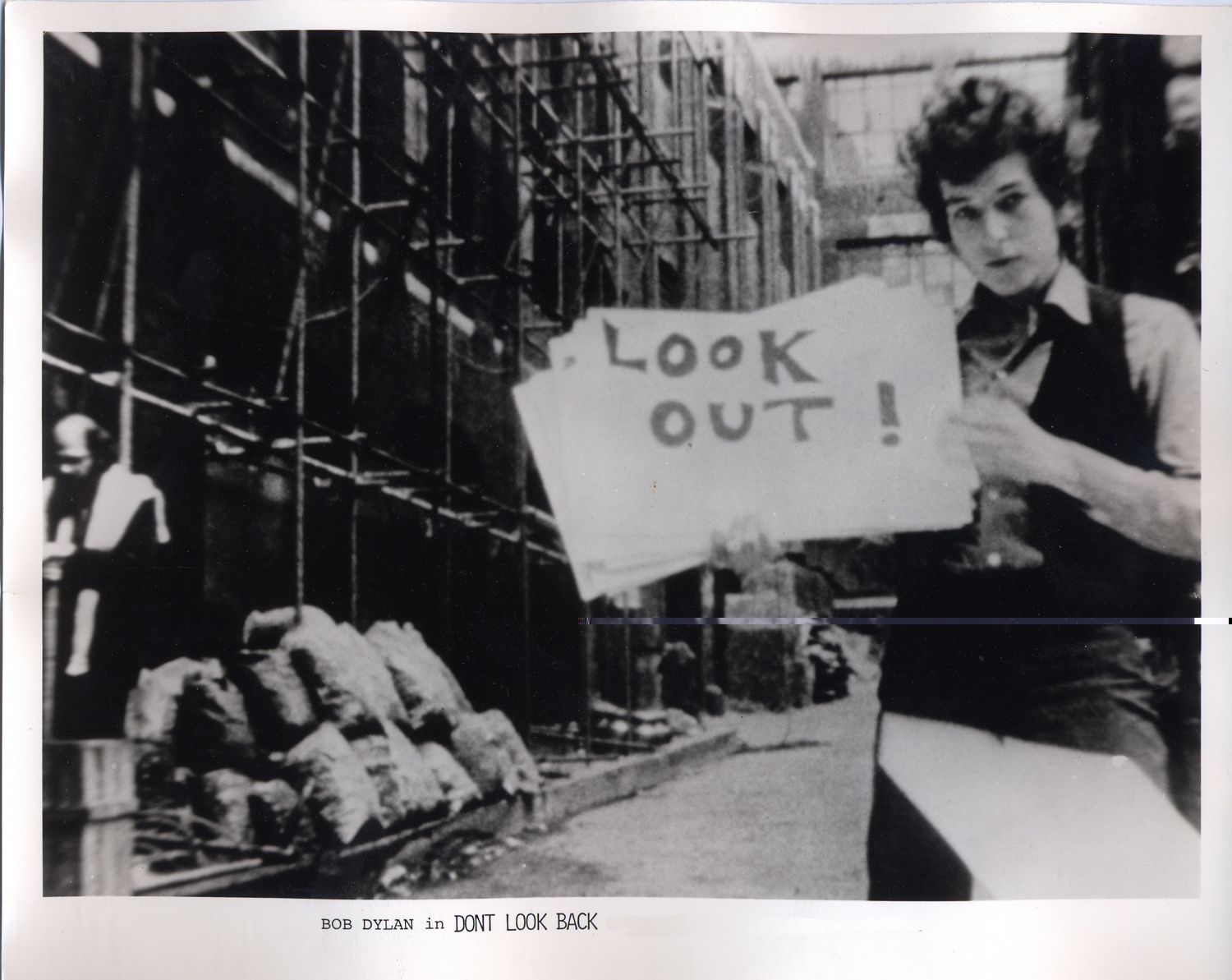

The journey that started in the early 1950s on the New York City subway has now spanned more than a half-century and produced more than 50 films, including 1967’s explosive concert documentary, Monterey Pop; 1965’s Don’t Look Back, Pennebaker’s revealing feature on Bob Dylan; and 1993’s The War Room, chronicling Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign. Pennebaker and Hegedus are being honored for their work this fall in both the weekly film series Stranger Than Fiction, which, in its 10-year history, has never before dedicated an entire season to a single filmmaking team, and by DOC NYC, New York’s largest documentary film festival, which will present the pair with a lifetime achievement award on Nov. 14, 2014.

Despite the accolades, Pennebaker says he owes much of his success to the subjects themselves, and the dedication of the team he worked with to pursue stories in a way that had never been done before.

“We weren’t dependent on things we couldn’t control,” he says today. “We weren’t really directors. We were beholders.”

Krystal Grow is a contributor to LIFE.com and TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instgram @kgreyscale

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com