When 25-year-old Muhammad Ali, the heavyweight champion of the world and the world’s single most famous Muslim, refused induction into the United States Army in the spring of 1967 (“War is against the teachings of the Koran,” he said. “I’m not trying to dodge the draft [but] we don’t take part in Christian wars.”), there was little doubt in his or in anyone else’s mind that there would be hell to pay for such a principled, public stand.

Sure enough, on the very day in April 1967 when he refused (three times) to step forward when his name was called for induction, Ali was stripped of his heavyweight title and his license to box was immediately suspended. Less than two months later, on June 20, 1967, a jury in Houston, Texas, convicted Ali of violating Selective Service laws. Sentenced to five years in prison, Ali appealed and, in June 1971 the U.S. Supreme Court reversed his conviction. (Ultimately, he served no jail time.) By the time of the Supreme Court’s ruling, he’d already had his license to box reinstated and had returned to the sport, winning two bouts and, famously, losing to the new heavyweight champion, Joe Frazier, in the March 1971 “Fight of the Century” at Madison Square Garden.

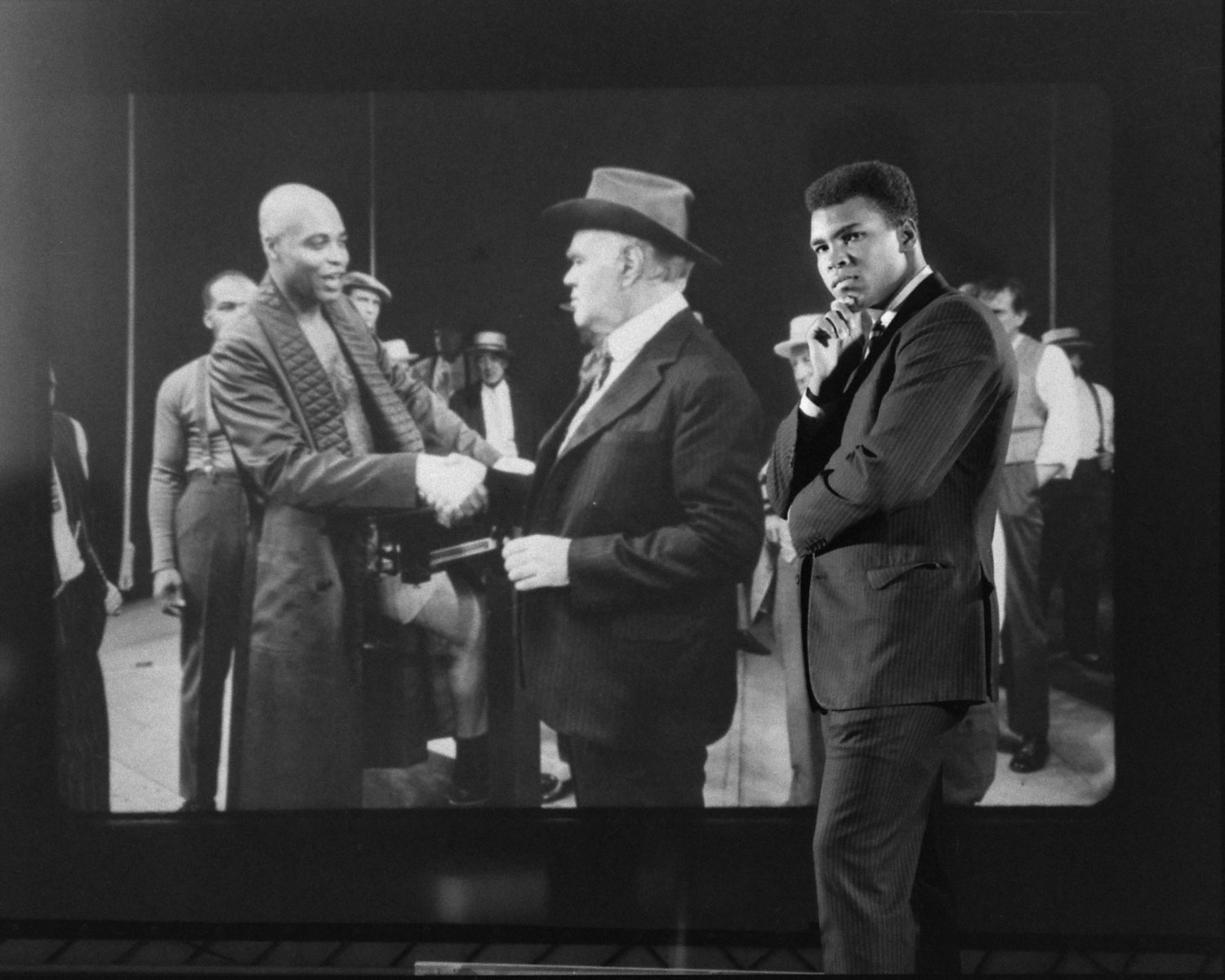

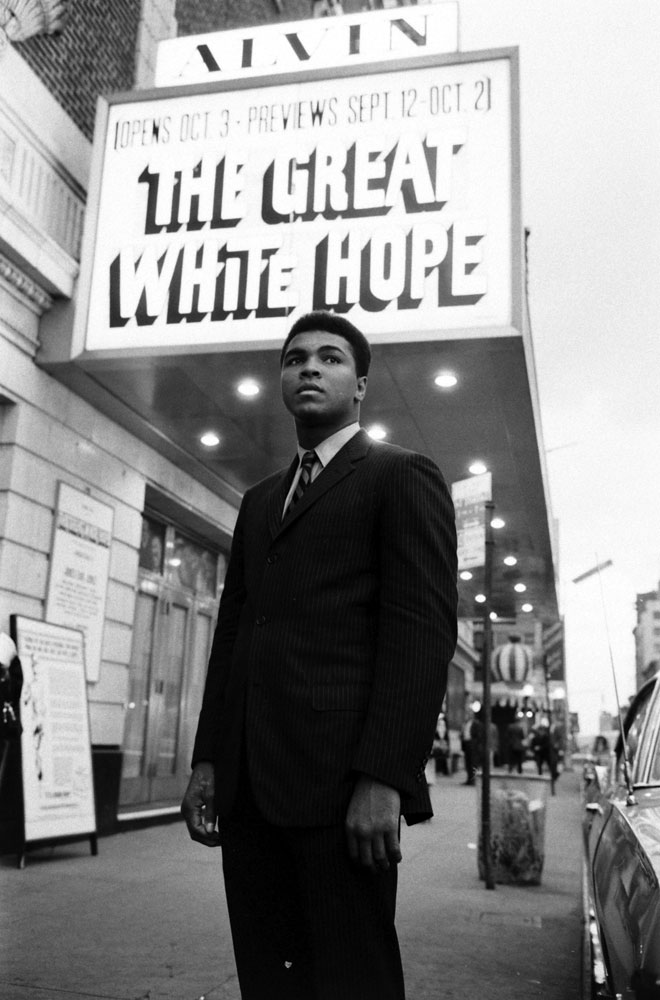

So, Ali was back, allowed once again to fight for the crown—a crown he eventually regained in jaw-dropping fashion in 1974’s legendary “Rumble in the Jungle” against George Foreman. But those many, many months when he was banned from the ring were history. They were gone. For years, while (largely) lesser fighters vied for the title and while his great nemesis, Joe Frazier, was relentlessly powering his way through the heavyweight ranks, Muhammad Ali was, in effect, in exile. Barred from the one place on Earth, the prizefighting ring, where his physical genius was permitted its fullest expression, the man Norman Mailer called “the World’s Greatest Athlete . . . the Prince of Heaven” was forced to find other outlets for his energy, other venues in which his unique personality could be given free rein.

For example, he spoke at colleges and universities—and was often greeted as a hero on campuses where anti-war sentiment was strong, and growing. But the one thing Ali never did was regret the decision and the actions that exiled him from boxing and kept the all-but-certain rewards—the riches, the adoring crowds, the glory—temporarily out of reach. He did not blame anyone else. He did not sulk.

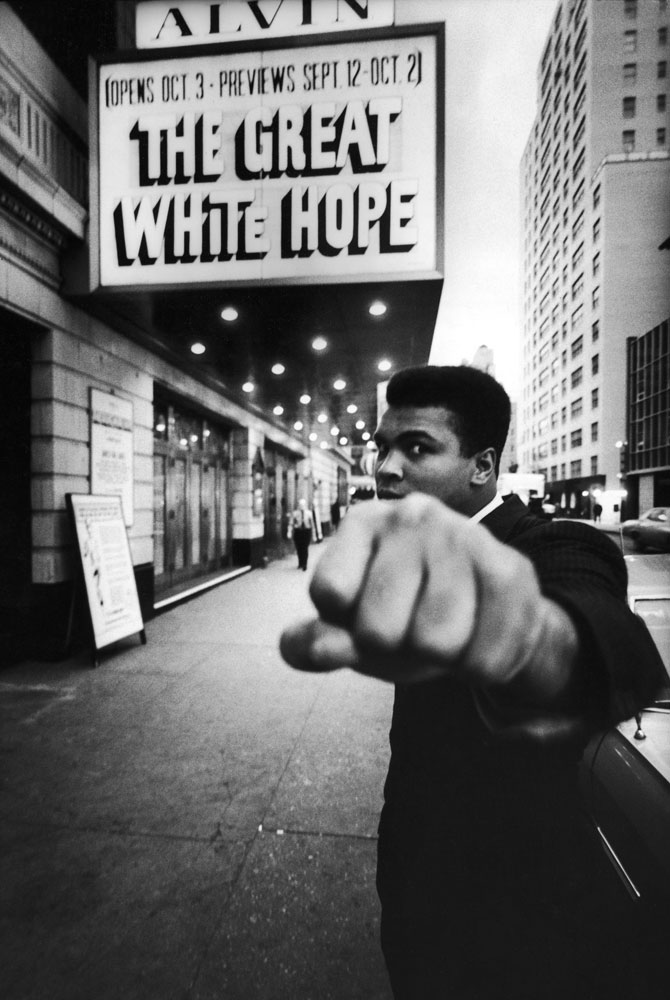

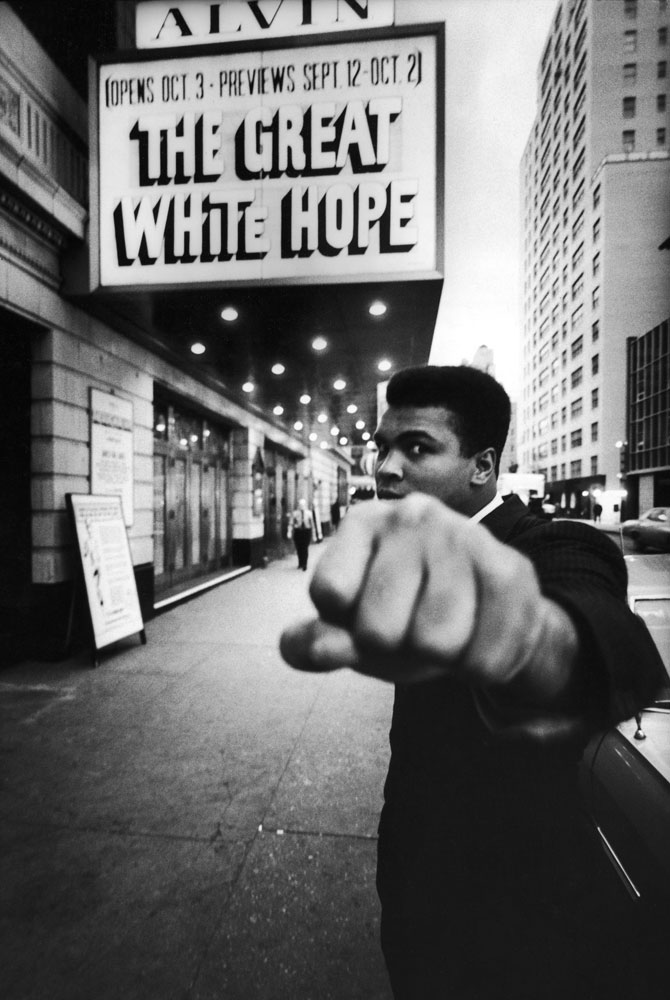

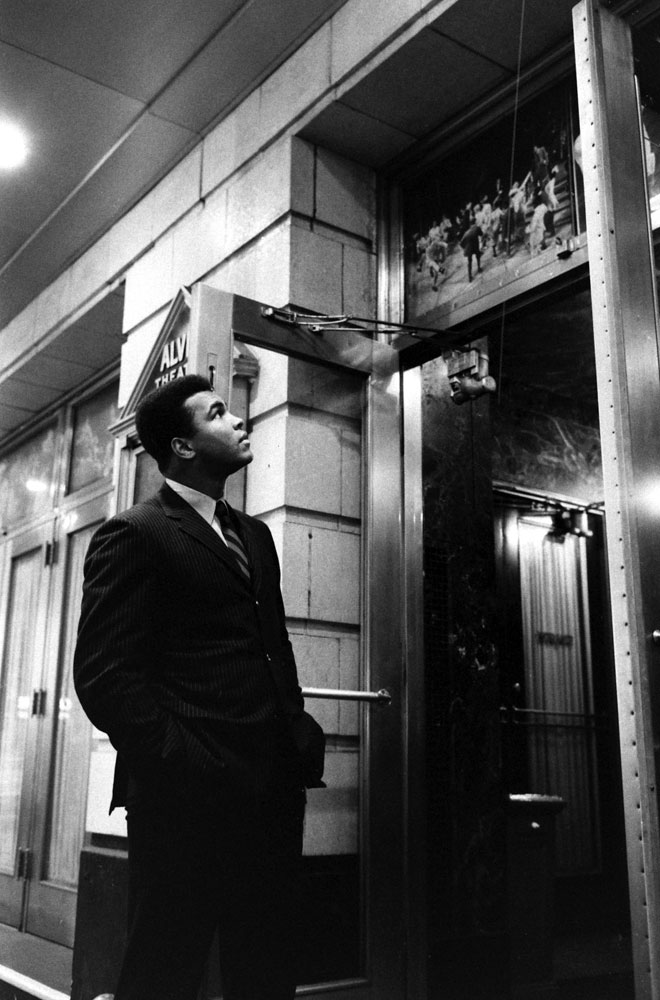

He came down West Fifty-Second Street [Pete Hamill wrote in an Oct. 1968 profile of the fighter in LIFE magazine], humming a song in the cold evening air, walking with the cold, bright swagger of a champion. . . . It had been 19 months since anyone had seen him do what he does better than anyone on earth—fight in a prize ring. On this evening in New York, it was as if he had never been away.

“Hey! There’s Cassius Clay!” a black girl said.

“Muhammad Ali, girl,” her boyfriend said. “Muhammad Ali. He changed his name, girl.”

People stepped out of a steak house to watch him go by. Auto horns beeped in salute. A middle-aged lady asked him to autograph her newspaper.

“Lookit me,” he said softly. “Bigger than ever. Bigger than boxing. As big as all history!”

He was loose and smiling and boyishly handsome. . . . It was as if nothing had ever happened to him that was ugly or malignant; as if no congressman had ever used his name in hatred, no anonymous editorial writer had savaged him, no draft board had ruled on his religious beliefs, no timid boxing commission had taken away that title which no one could take from him in the ring. . . . [He] was like the Cassius Clay of 1960 who had yet to learn that America could still strike down an “uppity” black man. . . .

And yet Ali does not seem bitter. “I’m happy,” he said, “’cause I’m free. I’ve made the stand all black people are gonna have to make sooner or later — whether or not they can stand up to the master.”

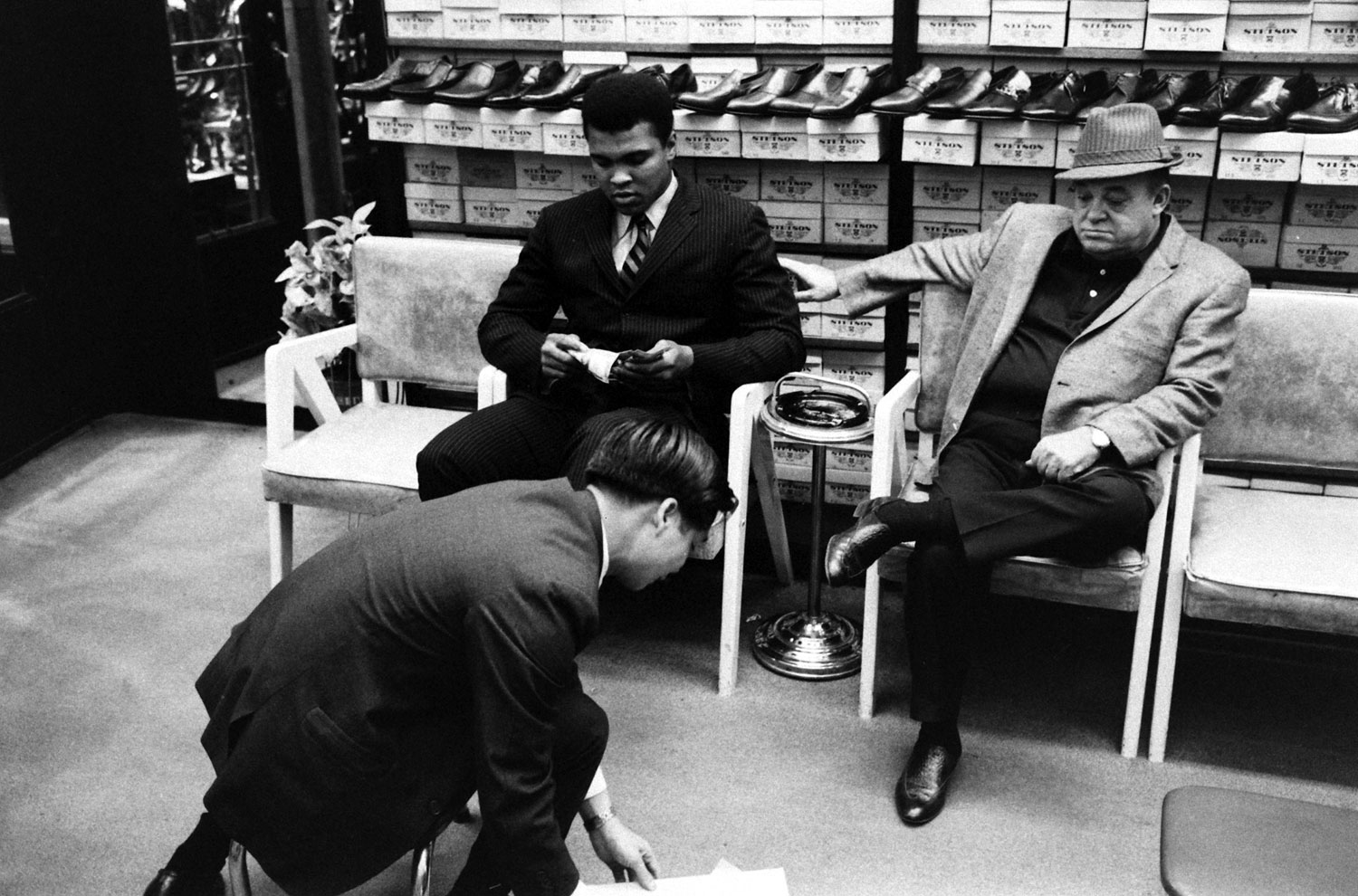

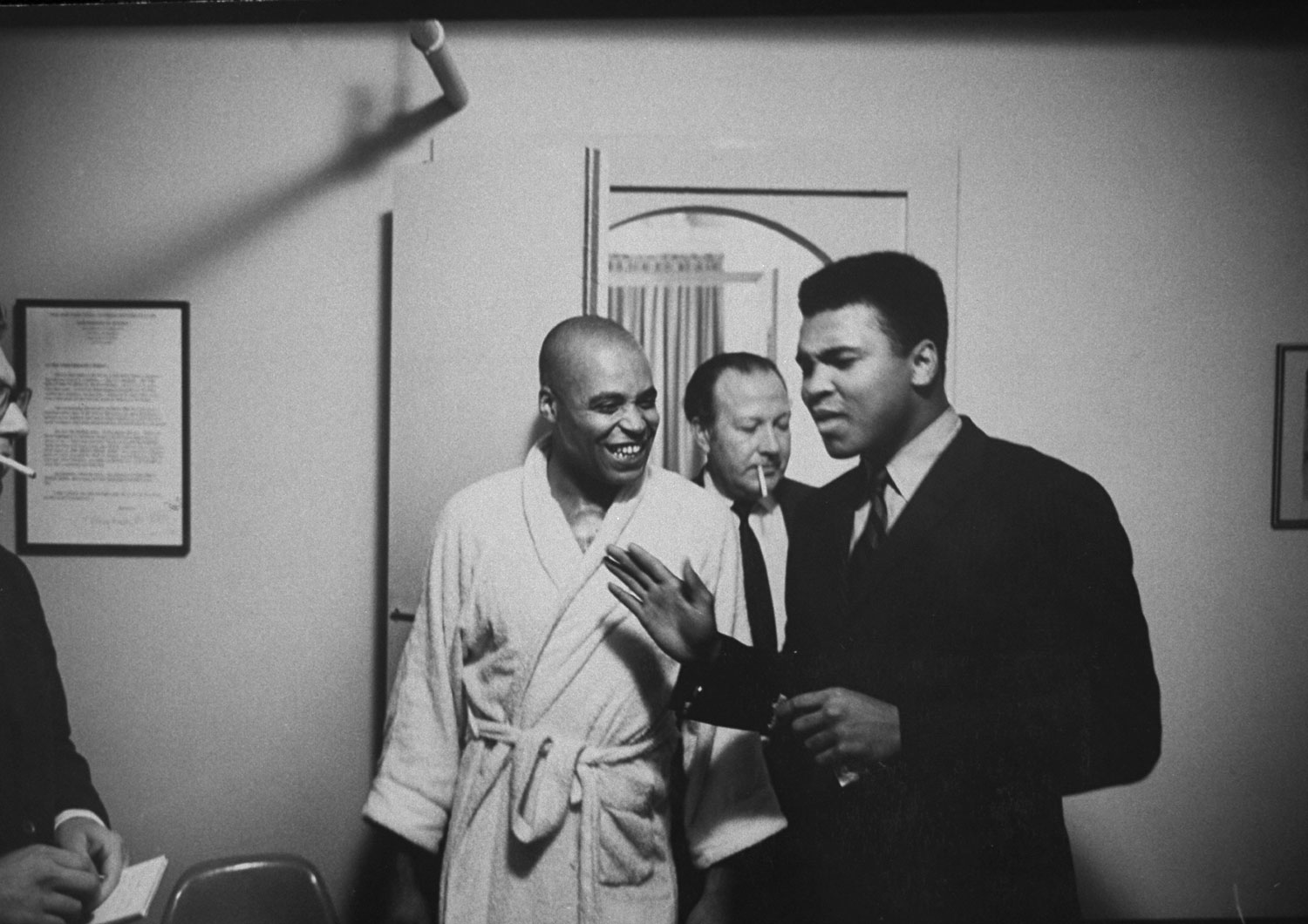

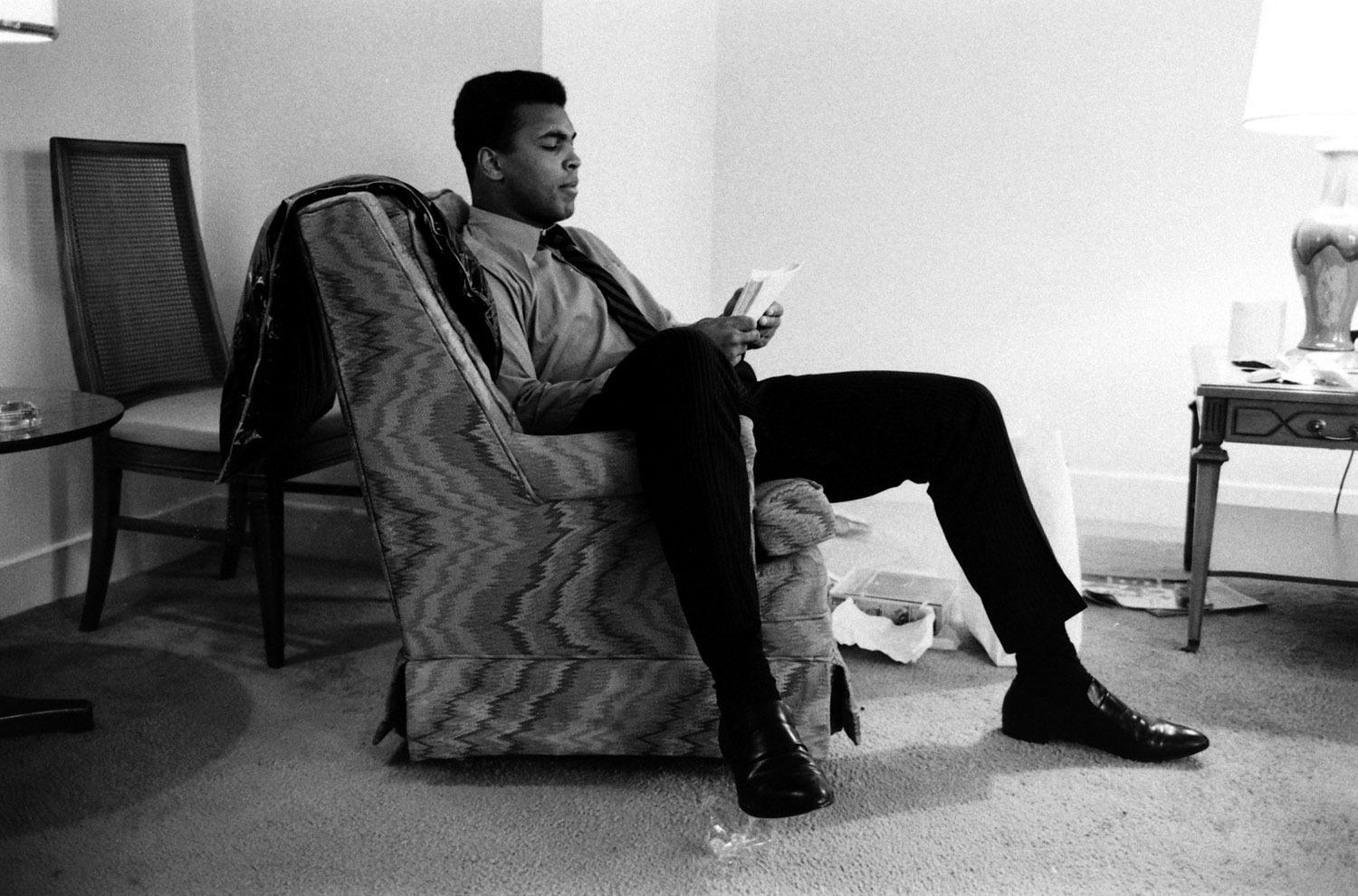

Here, LIFE.com pays tribute to the once and future champ with a series of photographs made in New York City in the midst of his exile from the ring: pictures of a preternaturally talented, charismatic young man at peace with his choices, and with his own conscience.

Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE.com

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Electoral College Actually Works

- Your Vote Is Safe

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- The Surprising Health Benefits of Pain

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com