On a recent trip home to visit my parents in Southern California, I sat at the kitchen table with my mother and, over a cup of coffee, enjoyed some leisurely mother-daughter chatter. She asked about my life in New York, and my job as a photo editor at TIME. Among the things I told her about was our June coverage of the 70th anniversary of D-Day, and the incredible story behind Robert Capa’s famous pictures of the Normandy invasion.

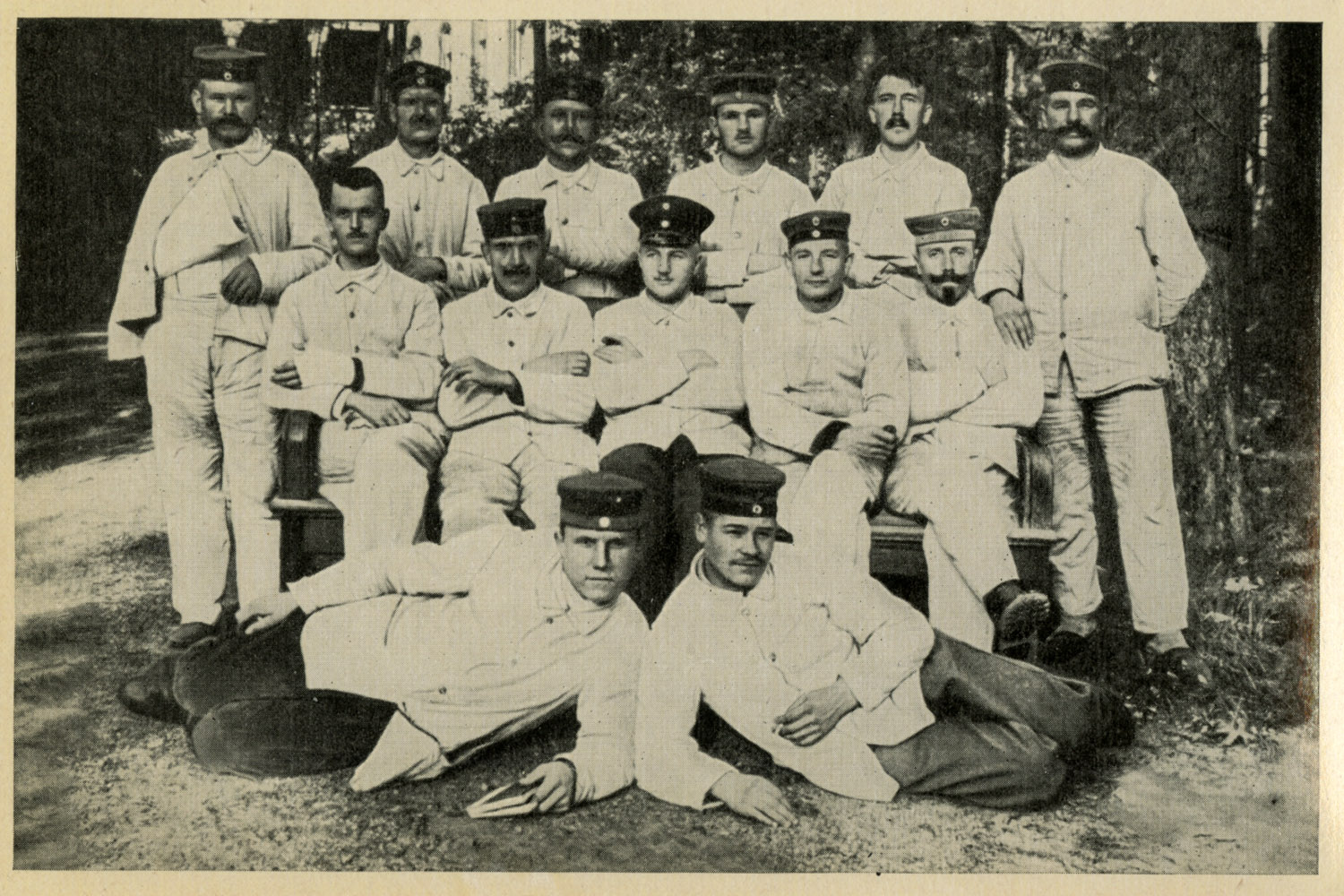

Incidentally, my grandfather, Staff Sgt. Paul T. Lipari (below), took part in D-Day, too, landing on Utah Beach in Normandy. Born in Easton, Penn., in 1914, the son of Sicilian immigrants and the second of eight children, Paul Lipari entered the U.S. Army in 1942 at the age of 28. A member of the 90th Infantry Division of Patton’s Third Army, he survived the D-Day assault that cost thousands of Allied lives, and served another 16 months before returning home. He was honorably discharged in 1945.

Since his death almost 15 years ago, my mother has occasionally shared with my brother, sisters and me the stories of her father’s life and service, and that day in the kitchen was no different. She told me things I’d already heard—and always enjoyed—about his training as a cook, marching with comrades down the Champs-Élysées, liberating the Flossenbürg concentration camp in Bavaria and the snapshots of Adolf Hitler that he brought back from the war. . . .

Wait. What?

My ears pricked up as I shifted from daughter mode to photo editor mode. Snapshots of Hitler? Now this was a story I hadn’t heard before.

Bringing souvenirs—sometimes bought, more often “liberated”—from foreign shores is something soldiers, sailors and marines have been doing since warfare was invented, and World War II was no different. But I had no idea what artifacts my grandfather might have come upon during his time in Europe. My mom went upstairs and returned minutes later with a large, floral-patterned box, and started organizing the contents on the kitchen table: photographs, newspaper clippings, maps, letters—and a small paper envelope containing what were, in fact, snapshots of the Führer.

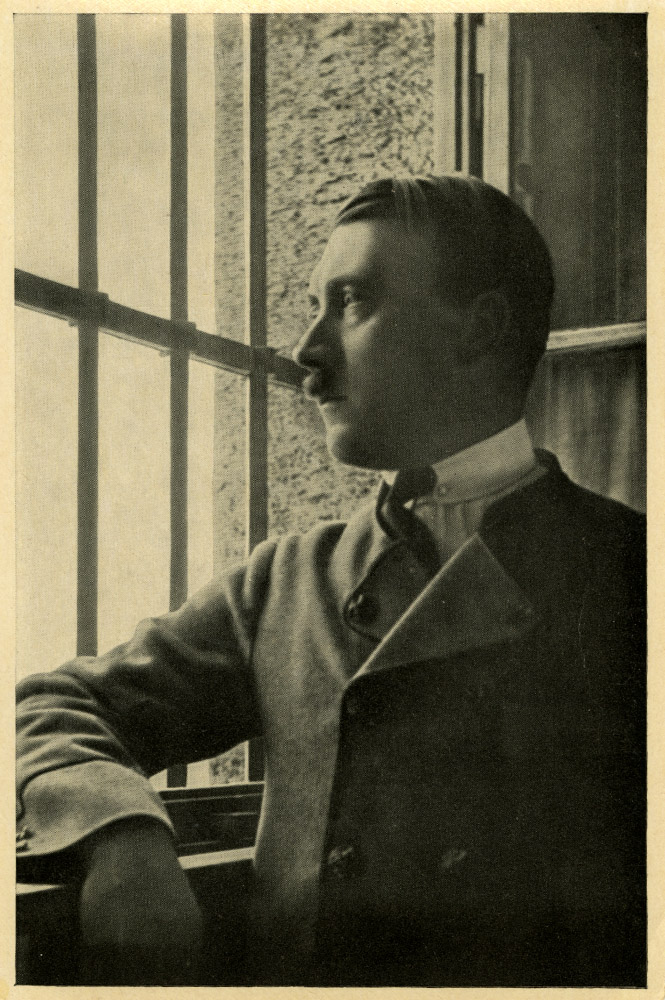

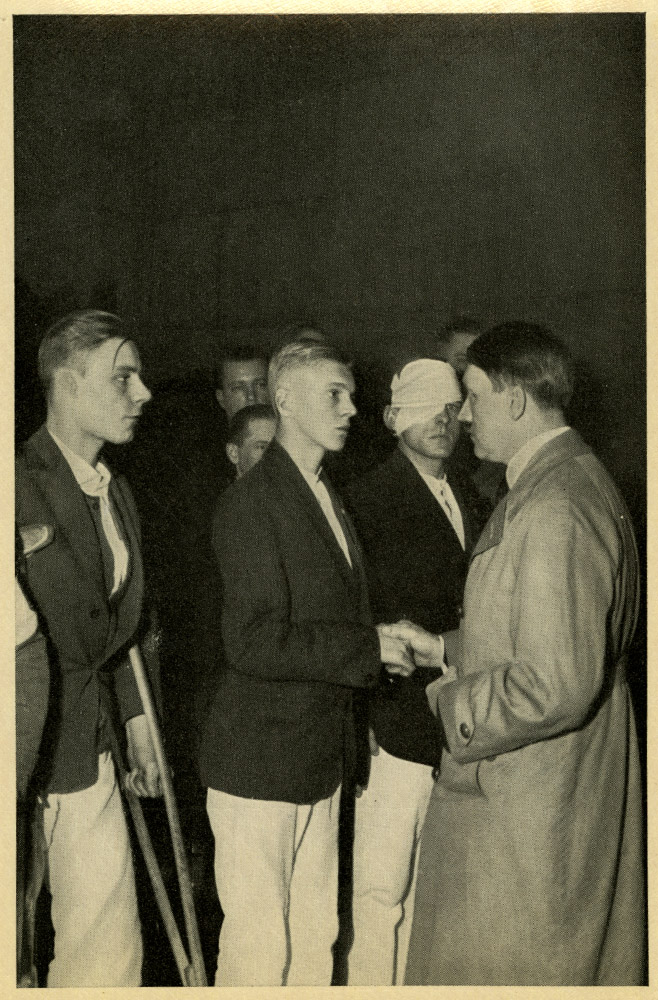

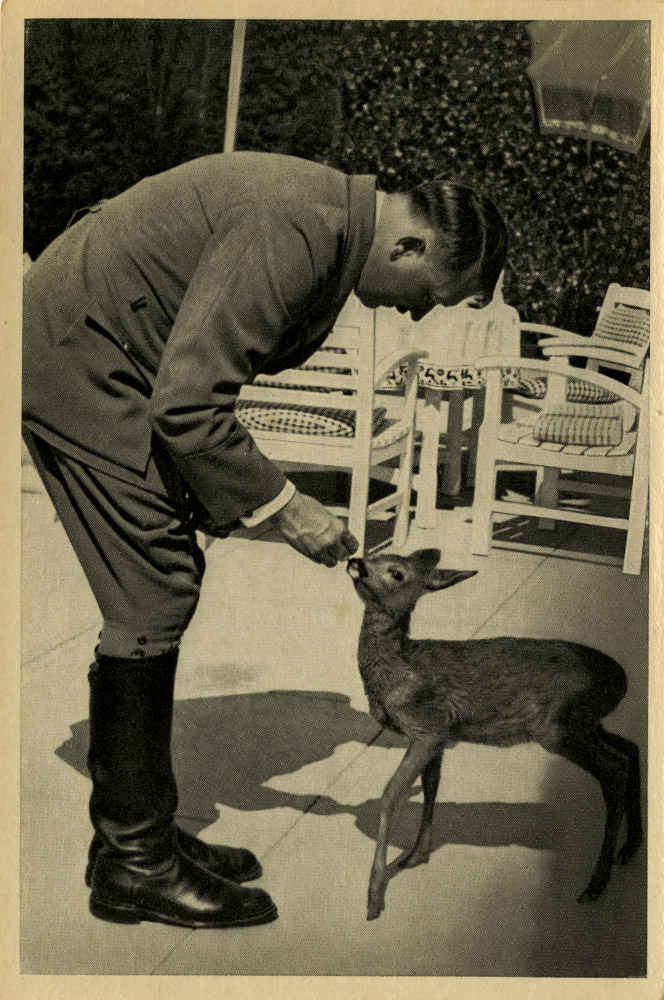

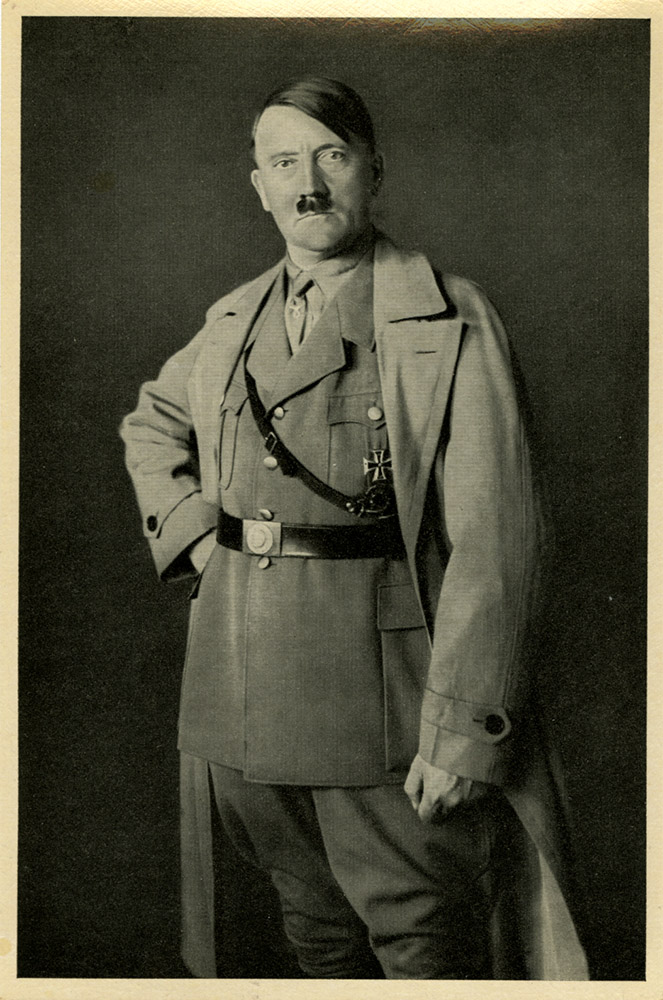

Adolf Hitler petting a fawn? Hitler watching a gymnastics festival? What were these?

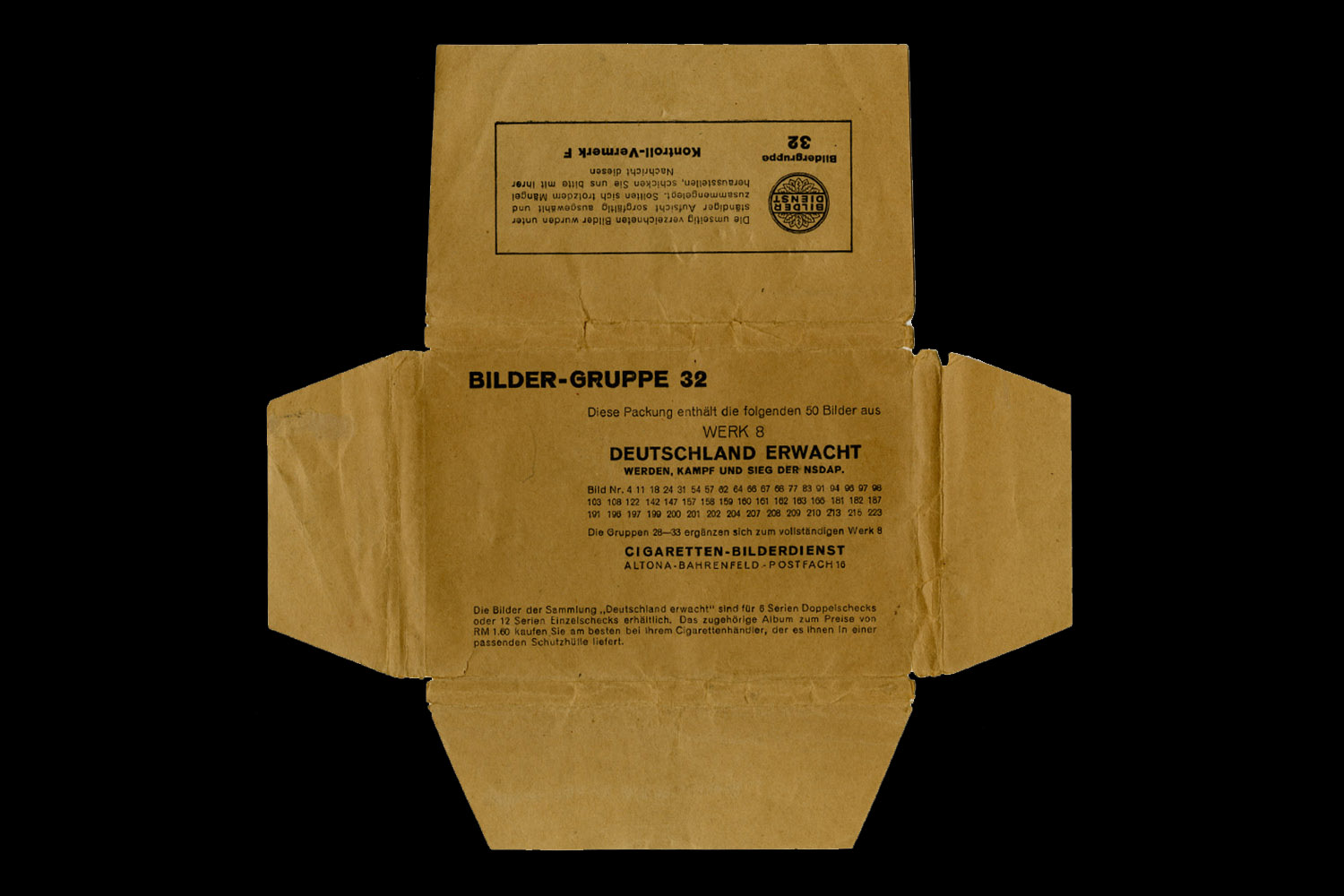

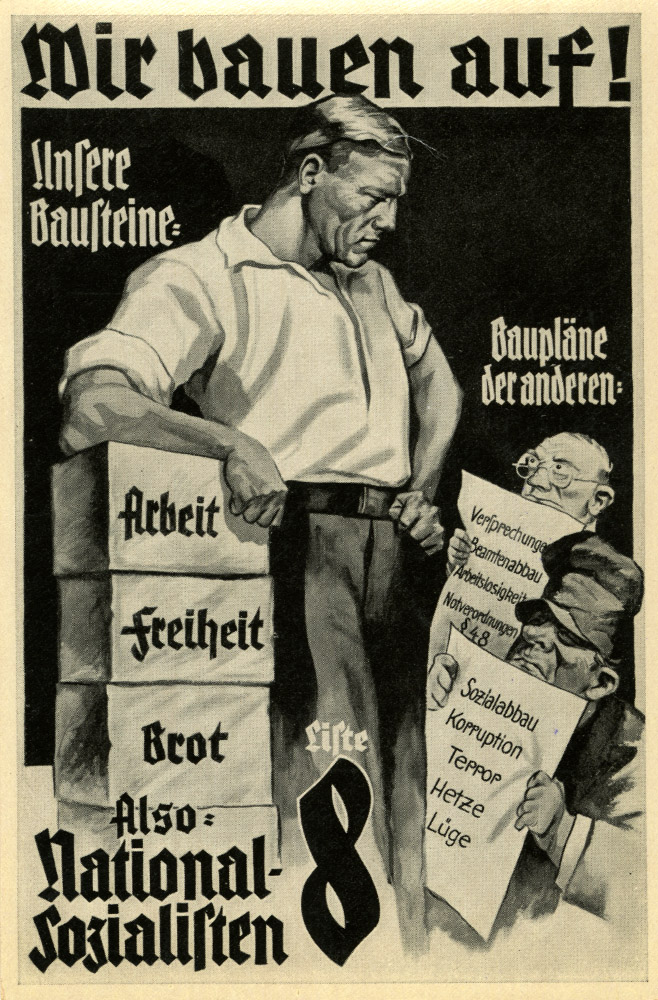

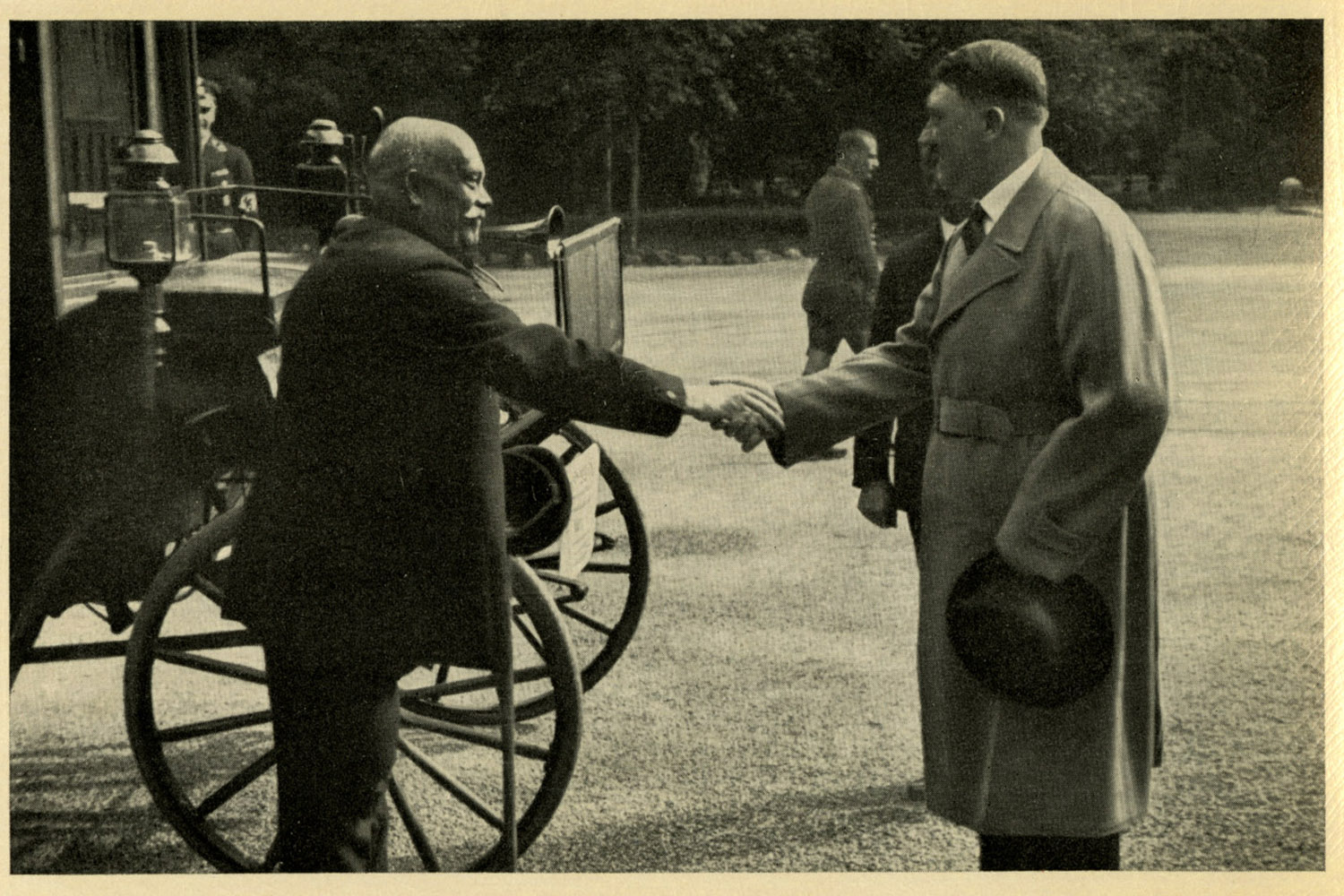

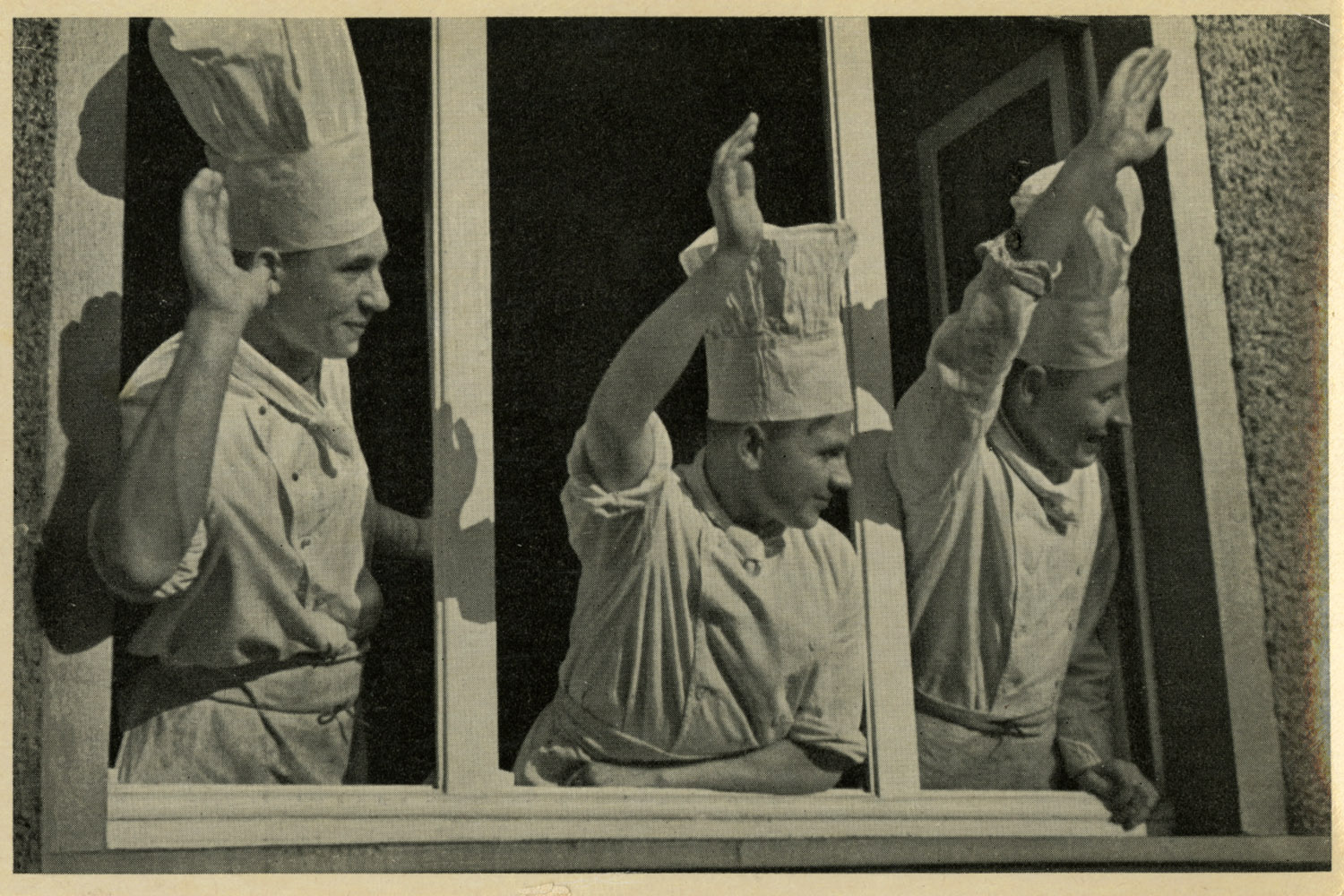

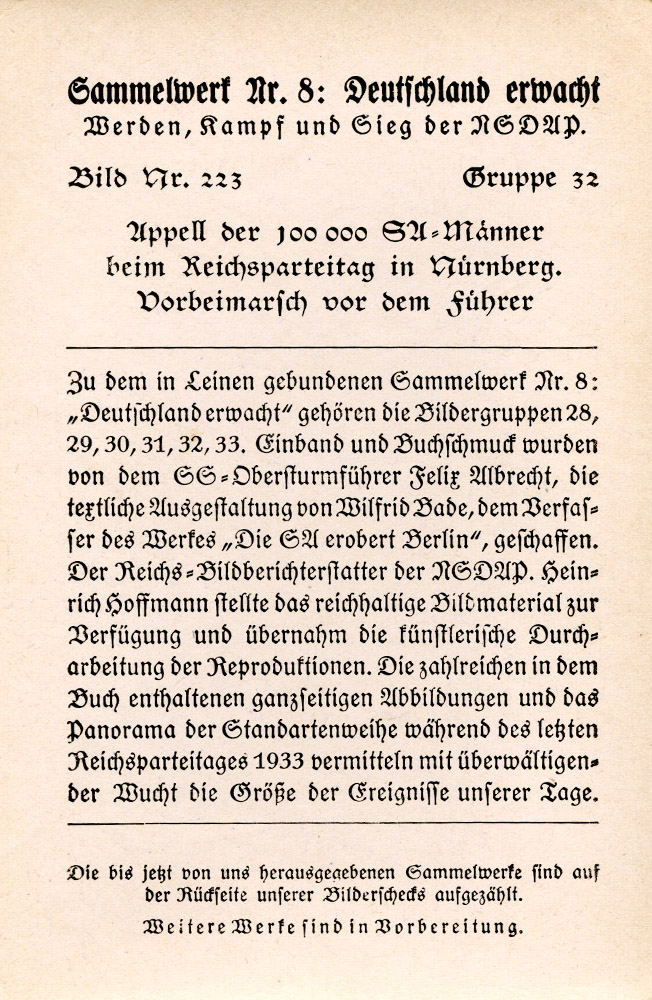

On the back of each photograph were numbers and a caption in German. I brought the packet back to New York for translation—with the idea of posting a gallery of the pictures online—and subsequently learned that the pictures were meant for a “cigarette picture book,” Deutchland Erwacht: Werden, Kampf Und Sieg Der NSDAP (“Germany Awakes: The Growth, Struggle and Victory of the NSDAP”).

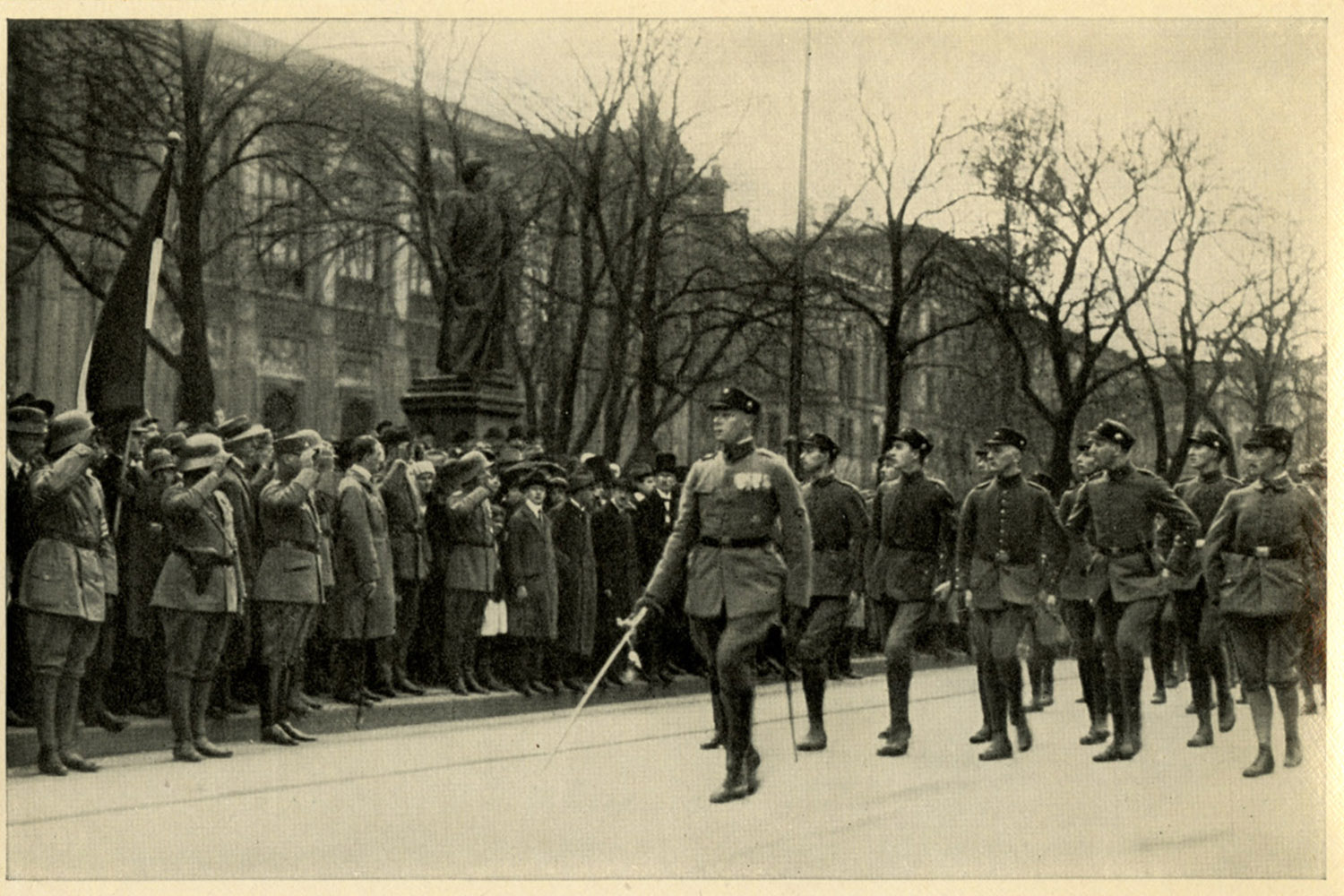

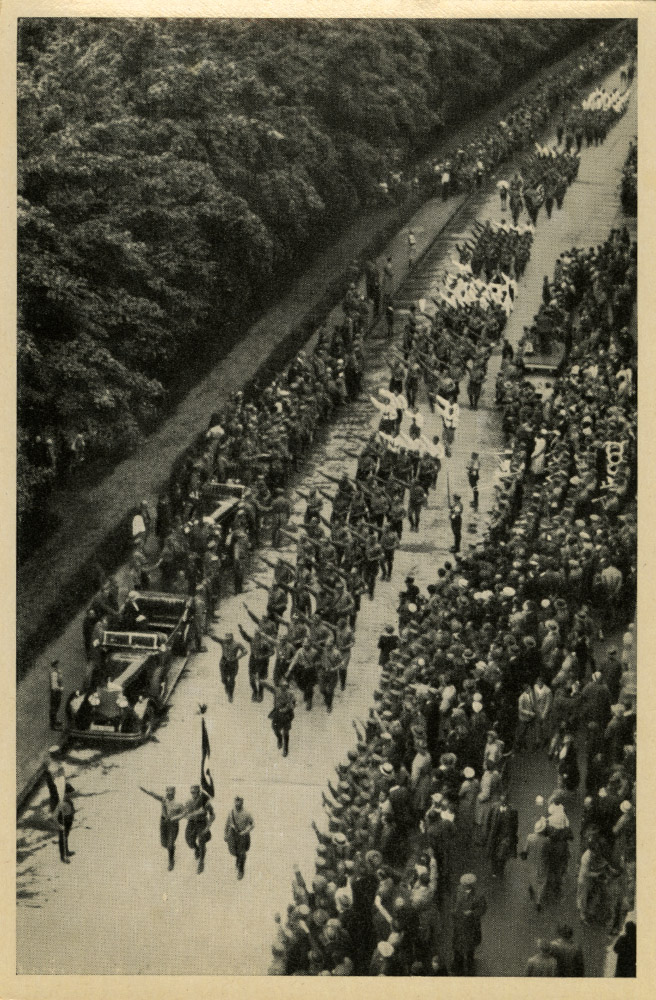

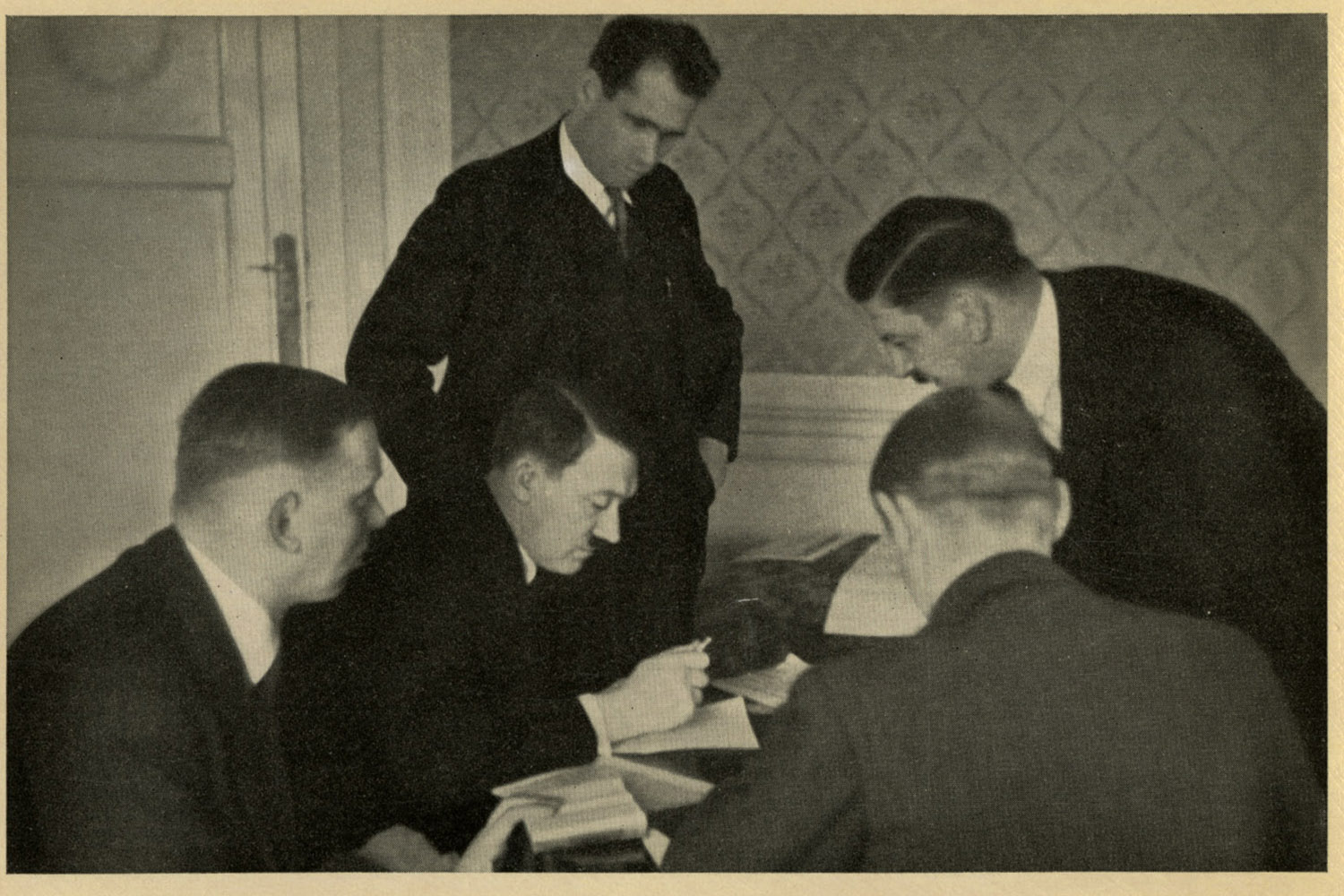

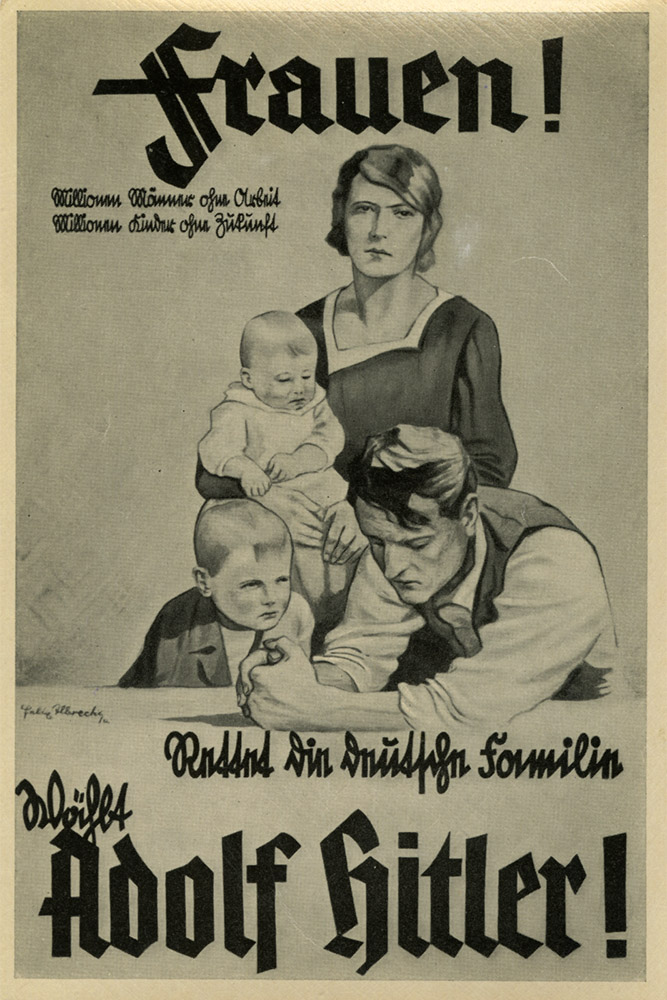

The purpose of Nazi-era cigarette books was, in short, blatantly propagandist. In the 1930s, after the rise of the Nazi Party, the National Socialist German Worker’s Party (NSDAP) collaborated with the German Cigarette Picture Service to deploy a series of photographs that would illustrate a carefully edited history of the party. The booklet itself contained text, and blank spaces to be filled in later with corresponding pictures. Smokers would find coupons in their cigarette packages, which they could then mail to the company. In return, each customer would receive a group of photographs to be mounted in the book. The end result: a picture-book that any patriotic, i.e., Nazi-affiliated, family could be proud of, chronicling the party’s ascendance under Hitler’s leadership.

How was it possible, I wondered, that I had never heard of this before? I was fully aware of the Nazis’ systematic use of propaganda to bolster the Reich’s creation myths and further the NSDAP agenda: publishing anti-Semitic newspapers; organizing book burnings; promoting Nazi-produced films and staging torchlight parades and grandiose rallies to stoke party pride. But why had I neither seen nor heard about what amounted to, in effect, Third Reich trading cards?

“Mass consumption and mass marketing had already come to Germany in the 1920s, and there was an appeal to a ‘collectors’ instinct’,” says Professor Volker Berghahn, Seth Low Emeritus Professor of History at Columbia University. “It was part of an attempt to draw a consumer into whatever things you were already producing, and that’s why the cigarette company was involved. And the Nazis had their own interest in getting people to learn their story. I’m sure many Hitler Youth were among the collectors, and were keen to fill their own albums.”

Most of the photographs in the series were made by Heinrich Hoffmann, the official photographer of the NSDAP, and for years the only person authorized to take pictures of Hitler. Hoffmann’s photos depict the Führer as heroic patriot; powerful leader; friend to men, women, children and animals. It’s hard to imagine not being influenced by exposure to such calculated political imagery—which is part of what makes the series, seen all these years later, so chilling.

After 1945, in an attempt to eradicate Nazism from Europe, the victorious Allies made it illegal to deal in Nazi propaganda and literature. These laws were enforced under subsequent German governments, which helps explain why Nazi artifacts such as the cigarette books are so rare within the country.

“Many Germans in the 1930s had a copy of Mein Kampf, [but] after 1945 you’d toss them into the dump, because you didn’t want to be associated with that book anymore,” notes Berghahn. “And, of course, much was destroyed by war. While there was mass circulation of books and albums like this in the Thirties, it presumably became a rare commodity by the mid-Forties.”

If my grandfather were alive today, I would have so many questions to ask him. Where did he find these cards? What caused him to pause and pick them up, and why did he bring them back home? I can’t help but wonder if he shared the same instinct that I have when I come across pictures like these: namely, a deep curiosity, as well as a desire to know more and to share that knowledge.

Today, almost 70 years after World War II ended, I feel I’m sharing what I’ve learned on his behalf.

Who could possibly foresee that sorting through photographs taken decades before I was born could bring me closer to my own family history? Or that it could, in a wholly unexpected way, teach me something new about my grandfather. All of which just goes to show, I guess, that you never know who or what you’ll encounter when you sit at a kitchen table with your mom and open up a box of memories

Bridget Harris is Senior Photography Producer at TIME

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com