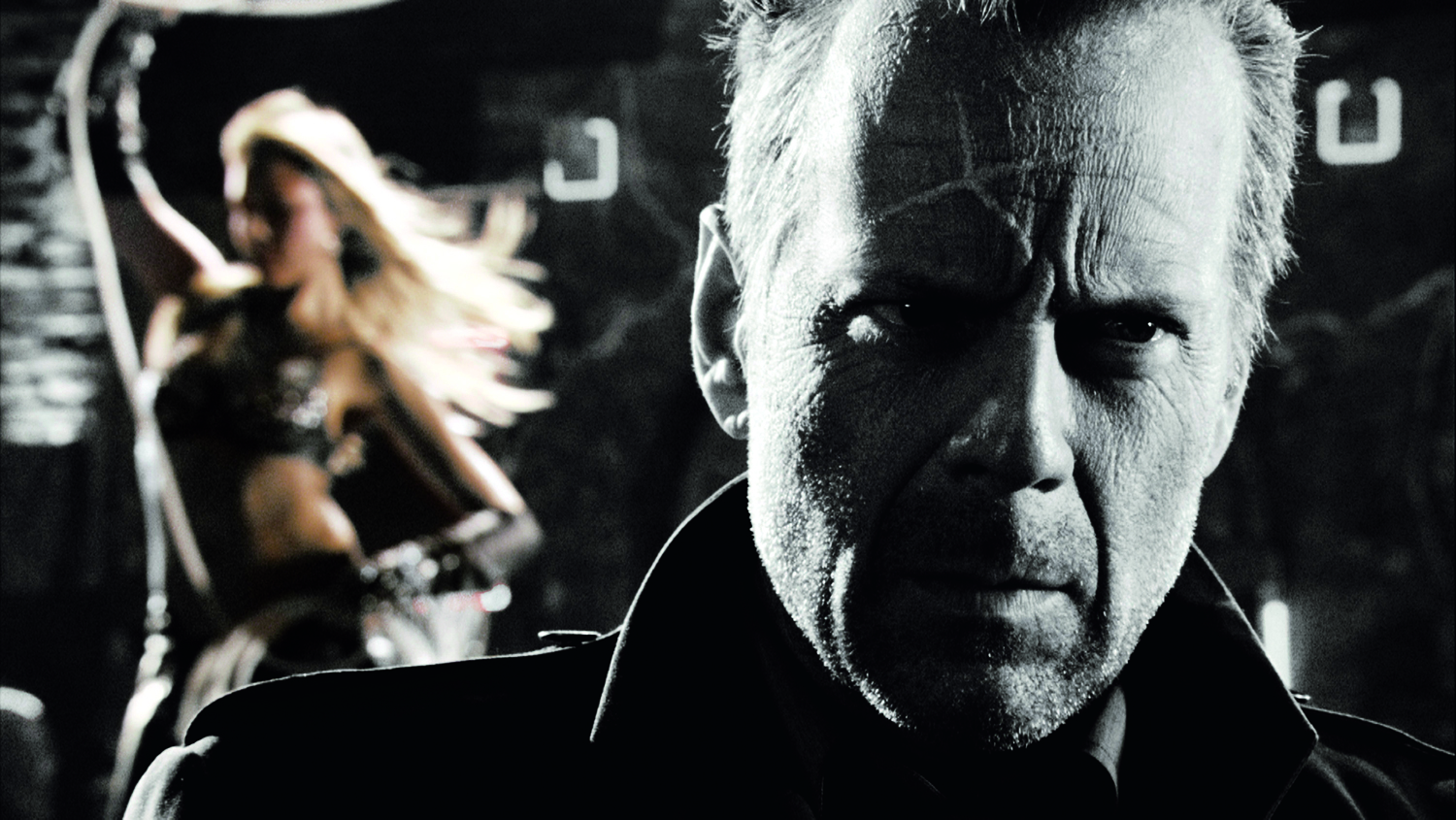

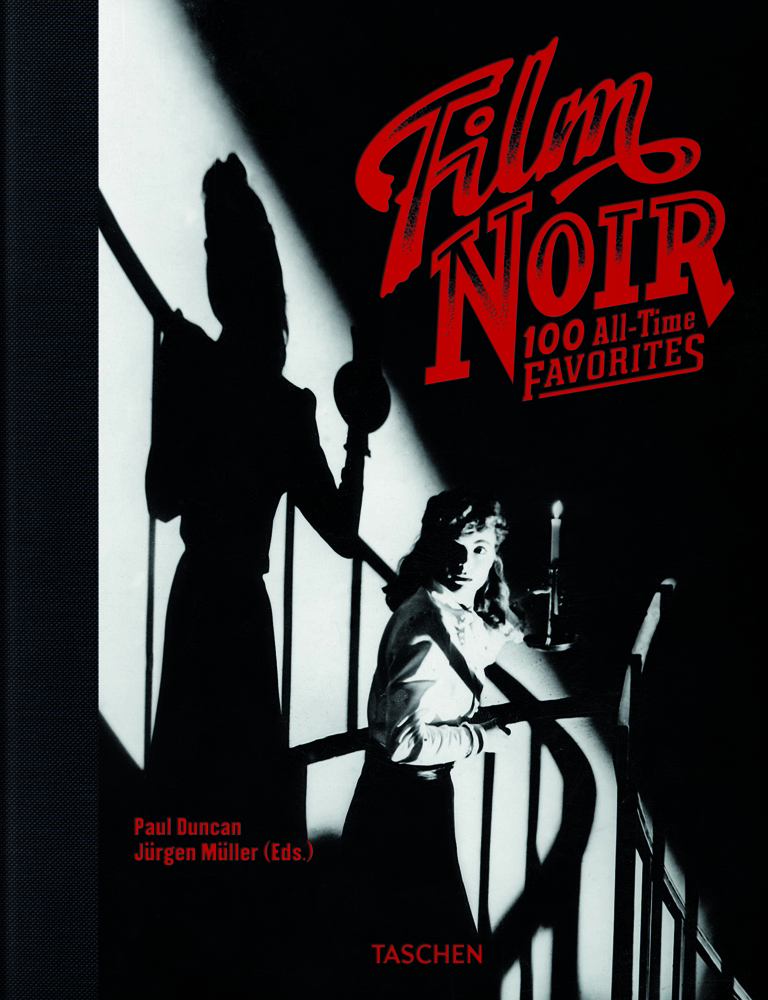

Most people who love movies have seen a good number of noir films — whether they knew they were watching noir or not. After all, scores of classics — and countless lesser, but still thoroughly entertaining, films — from the 1940s and ’50s are noir titles: The Maltese Falcon, Double Indemnity, Detour, Gilda, Out of the Past, They Live by Night, White Heat, Touch of Evil and on and on. Here, LIFE.com celebrates noir with a gallery of photos from some of the greatest films in the genre (including more recent neo-noir gems) and an excerpt, below, from writer-director Paul Schrader‘s introduction to TASCHEN’s new book, Film Noir: 100 All-Time Favorites.

In 1946 French critics, seeing the American films they had missed during the war, noticed the new mood of cynicism, pessimism, and darkness which had crept into the American cinema. The darkening stain was most evident in routine crime thrillers, but was also apparent in prestigious melodramas.

The French cineastes soon realized they had seen only the tip of the iceberg: as the years went by, Hollywood lighting grew darker, characters more corrupt, themes more fatalistic, and the tone more hopeless. By 1949 American movies were in the throes of their deepest and most creative funk. Never before had films dared to take such a harsh uncomplimentary look at American life, and they would not dare to do so again for twenty years.

Film noir is not a genre. . . . It is not defined, as are the Western and gangster genres, by conventions of setting and conflict, but rather by the more subtle qualities of tone and mood. It is a film “noir,” as opposed to the possible variants of film gray or film off-white.

Film noir is also a specific period of film history, like German Expressionism or the French New Wave. In general, film noir refers to those Hollywood films of the ’40s and early ’50s that portrayed the world of dark, slick city streets, crime and corruption.

Film noir is an extremely unwieldy period. It harks back to many previous periods: Warner’s 30 gangster films, the French “poetic realism” of Carné and Duvivier, Von Sternbergian melodrama, and, farthest back, German Expressionist crime films. . . . Film noir can stretch at its outer limits from The Maltese Falcon (1941) to Touch of Evil (1958), and most every dramatic Hollywood film from 1941 to 1953 contains some noir elements.

There are also foreign offshoots of film noir, such as The Third Man, Breathless, and Le Doulos. Almost every critic has his own definition of film noir, and a personal list of film titles and dates to back it up. Personal and descriptive definitions, however, can get a bit sticky. A film of urban nightlife is not necessarily a film noir, and a film noir need not necessarily concern crime and corruption. Since film noir is defined by tone rather than genre, it is almost impossible to argue one critic’s descriptive definition against another’s.

— Paul Schrader

Film Noir: 100 All-Time Favorites is available from TASCHEN.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com