Walker Evans was never one to bow to authority. A photographer celebrated for his landmark work with the Depression-era Farm Security Administration, he fostered a reputation as a rebel and contrarian, determined to make work that he believed answered to a calling nobler than press, propaganda or politics. Evans was an artist.

A promising writer early in life, the St. Louis native (b. 1903) was seduced by the powerful work of Eugène Atget and Paul Strand in his mid-twenties. He developed an uncompromising eye that blended an abstract, modernist sensibility with a searing social conscience. Evans was an avid reader of early photo-based journals, including Alfred Steiglitz’s legendary Camera Work, and had developed a keen awareness of the power of a finely edited photographic sequence, as well as the visual impact of typography and graphic design. For Evans, words, images and layout were more than haphazard parts of a disposable whole.

Having published his photos in TIME, Harper’s Bazaar and Architectural Digest, along with a groundbreaking solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1938 and the publication of his hugely influential monograph, American Photographs, Evans was hired in September 1945 as the only staff photographer at Fortune magazine, a seemingly unlikely fit for a photographer with a knack for glorifying the ordinary. He pitched unusual stories that, in less aesthetically diligent hands, would never have held their own in the luxurious pages of Fortune. But Evans, who was described in a 1948 editorial as “the most freewheeling member of the Fortune staff,” followed through with his lofty proposals and emerged with routinely brilliant spreads.

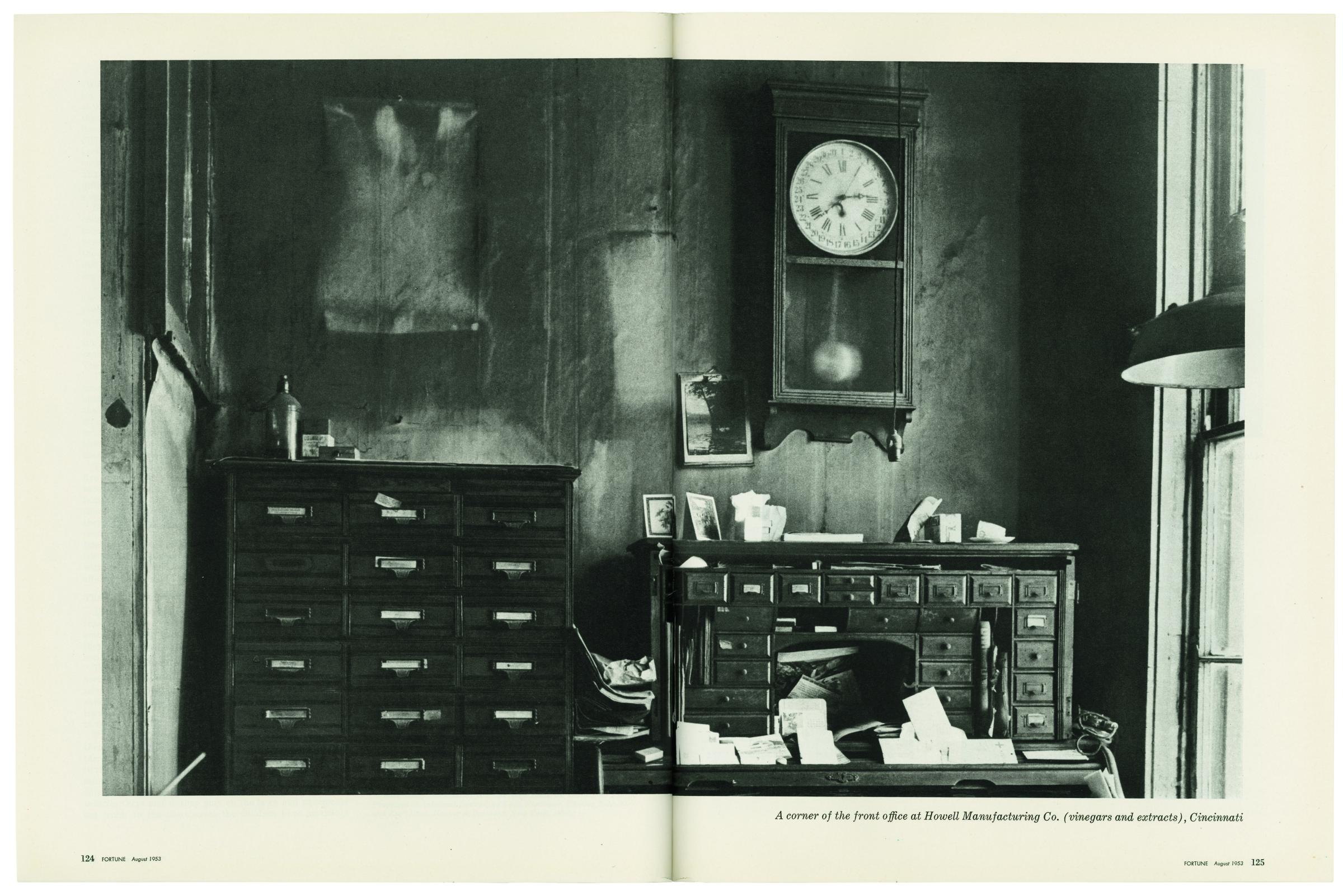

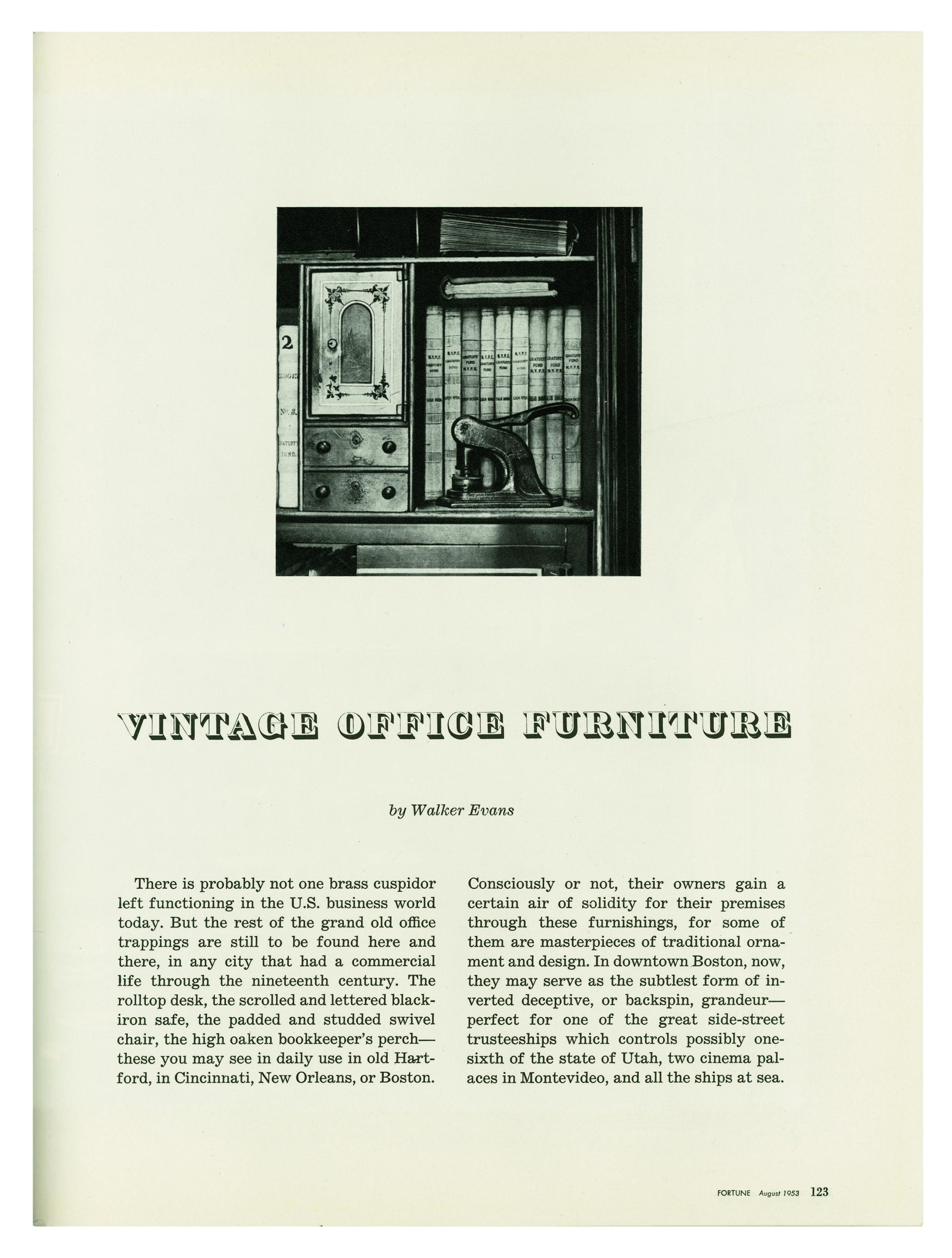

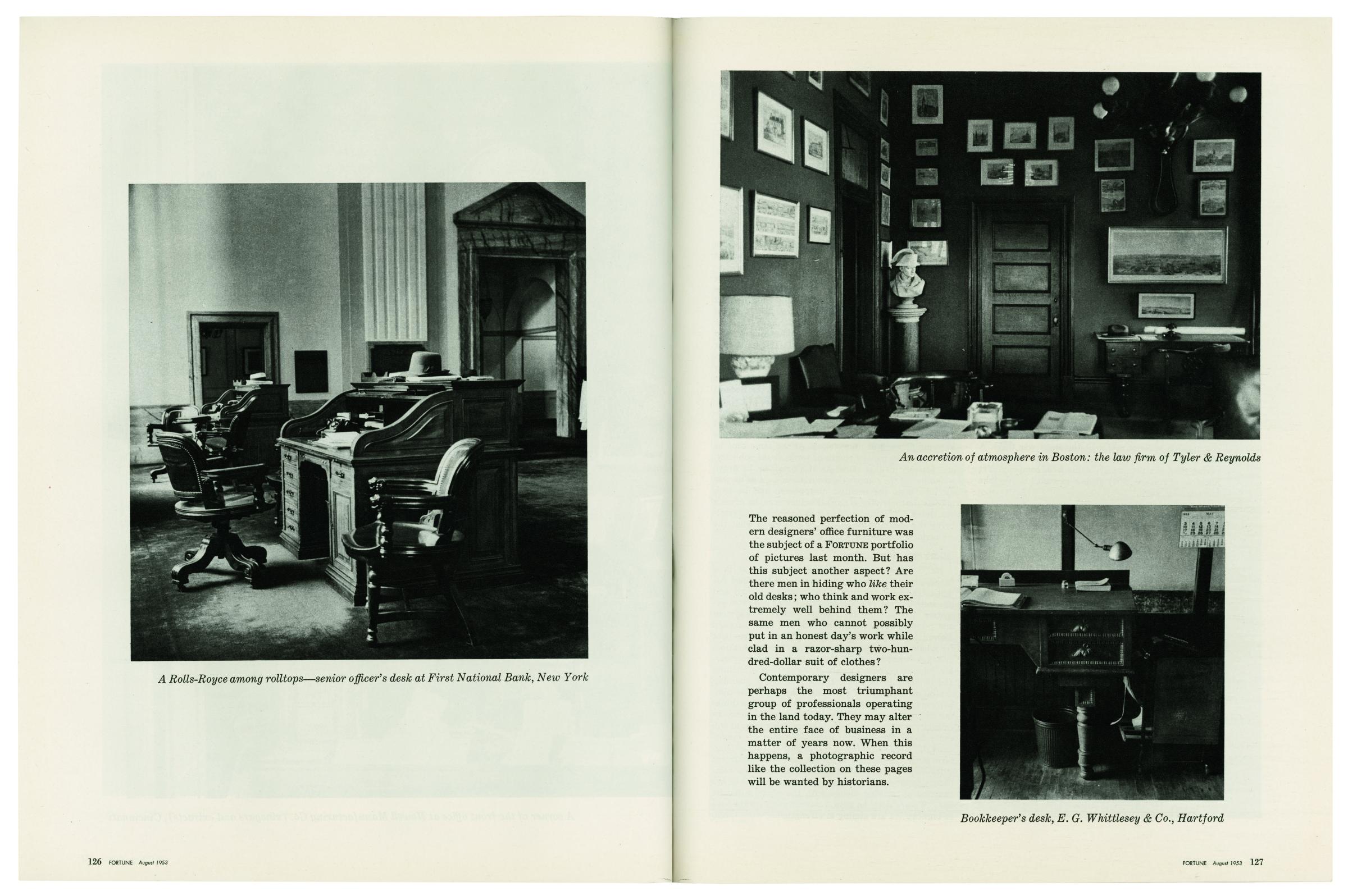

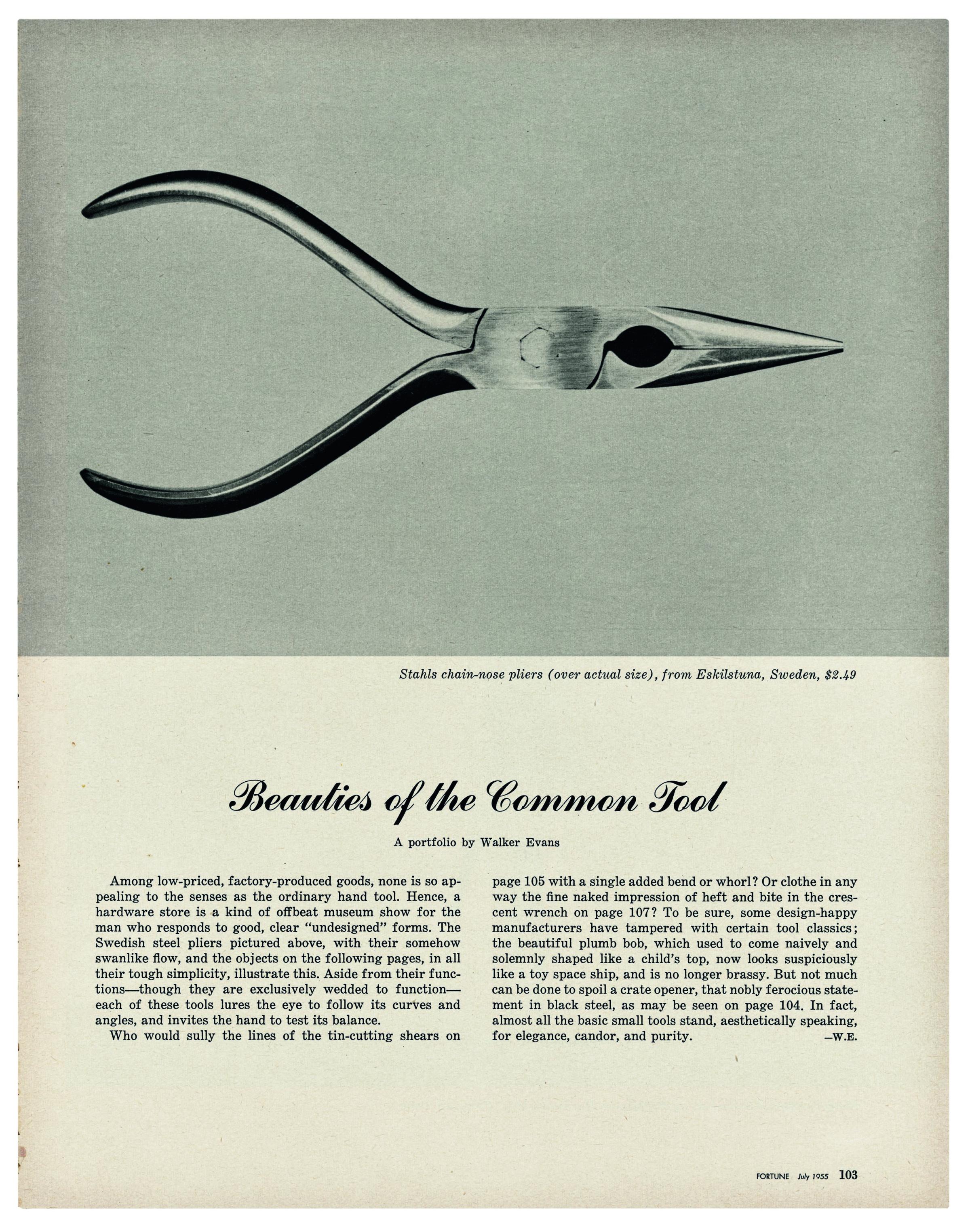

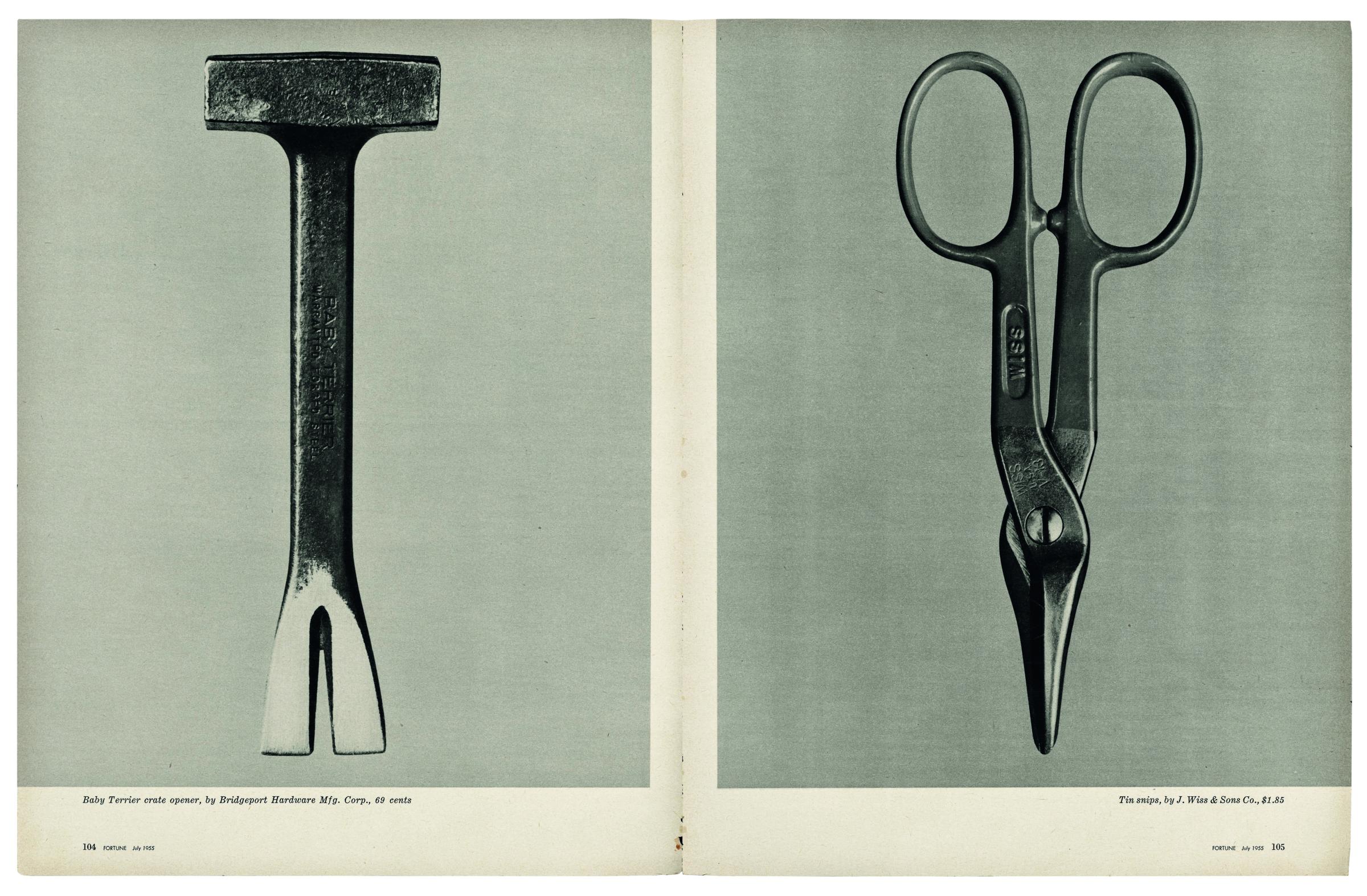

Case in point: Evans’ August 1953 feature on vintage office furniture, a five-page spread of regal black and white photos dedicated to the quiet dignity of well-worn yet elaborately designed roll-top desks and leather-padded chairs. The following year, Evans took another five pages to honor the “Beauties of the Common Hand Tool,” a sprawling ode to the “undesigned” splendor of pliers, tin snips and crescent wrenches, shot with a glossy studio precision typically reserved for high-end catalogs and advertisements.

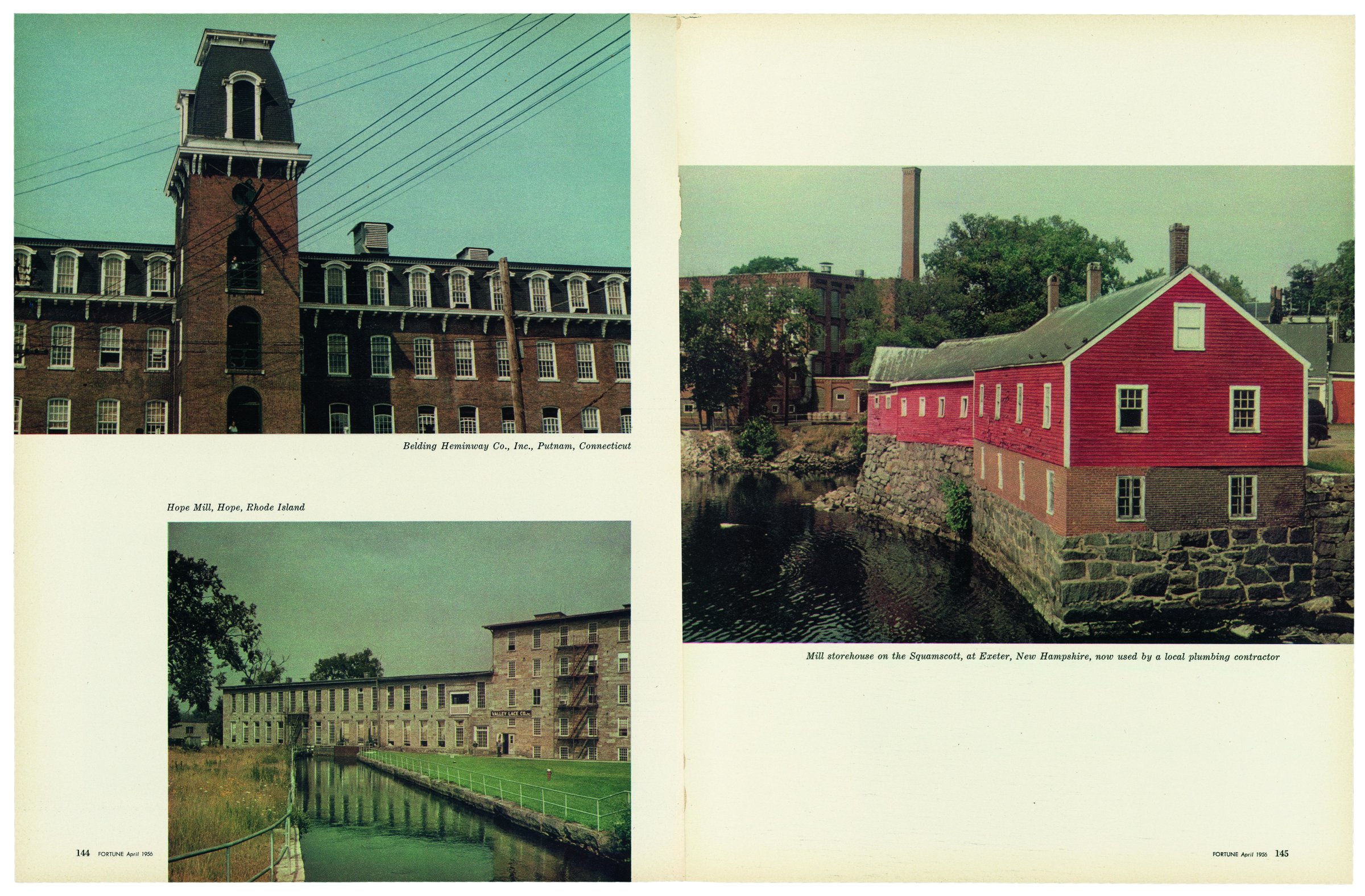

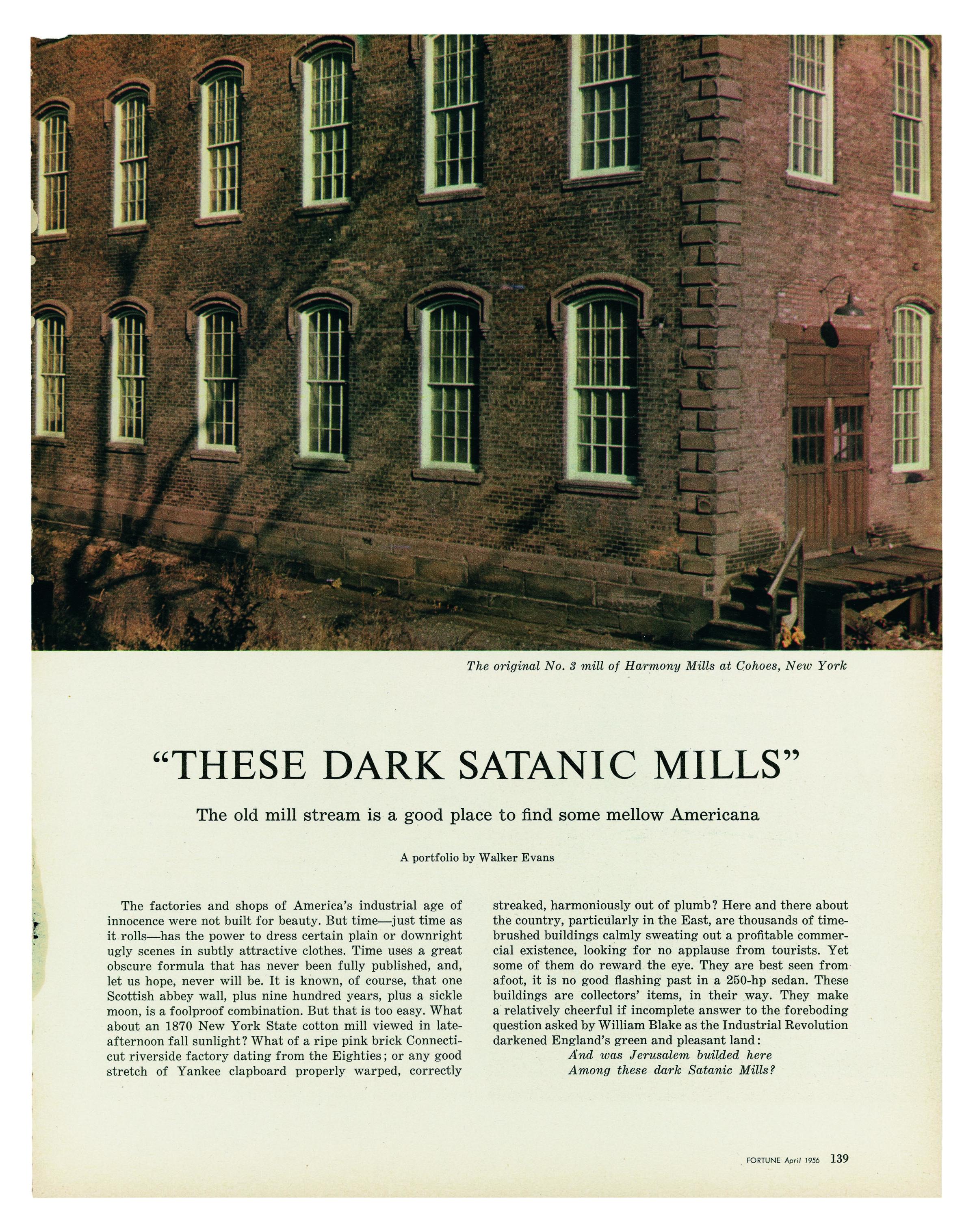

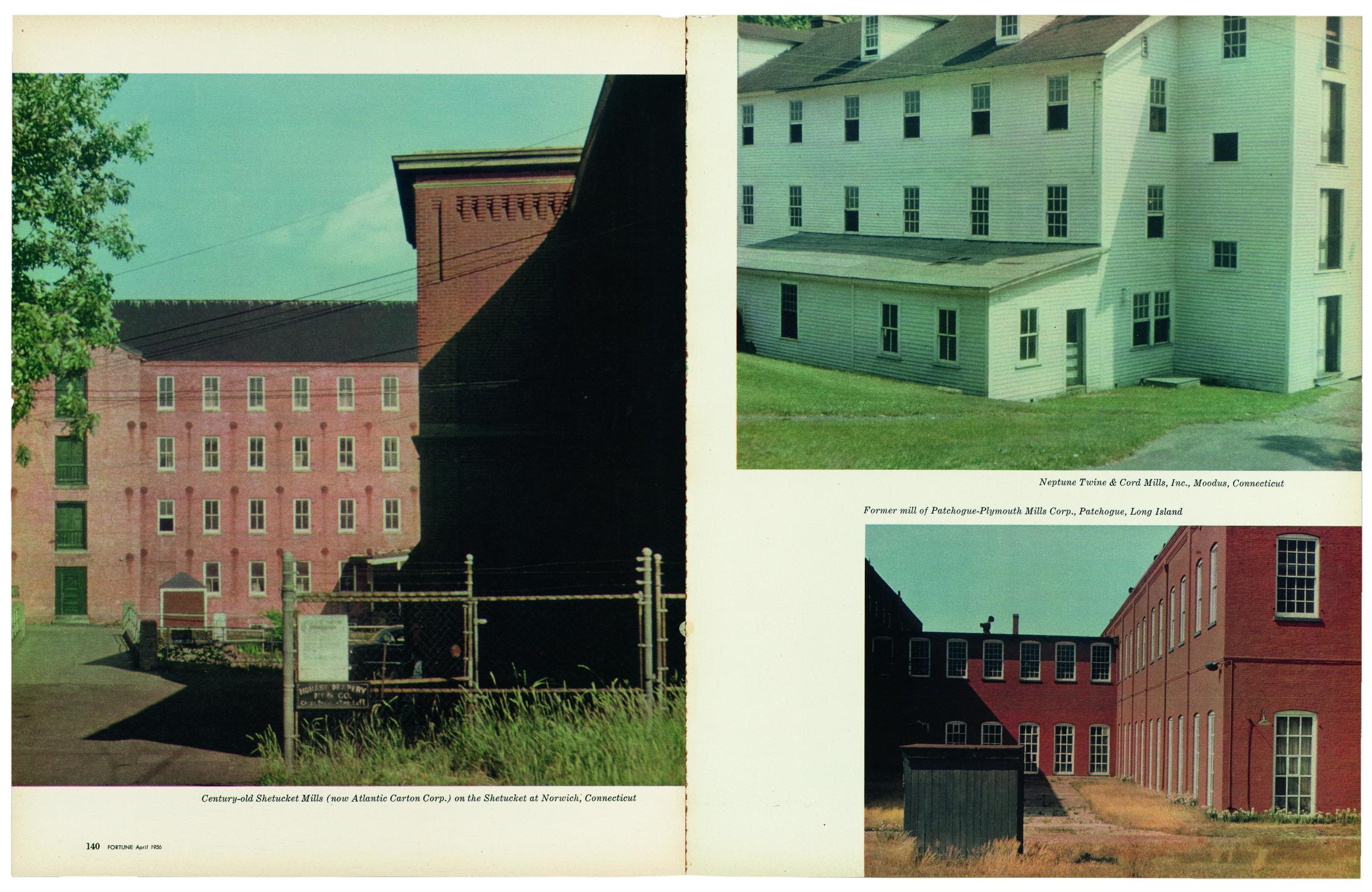

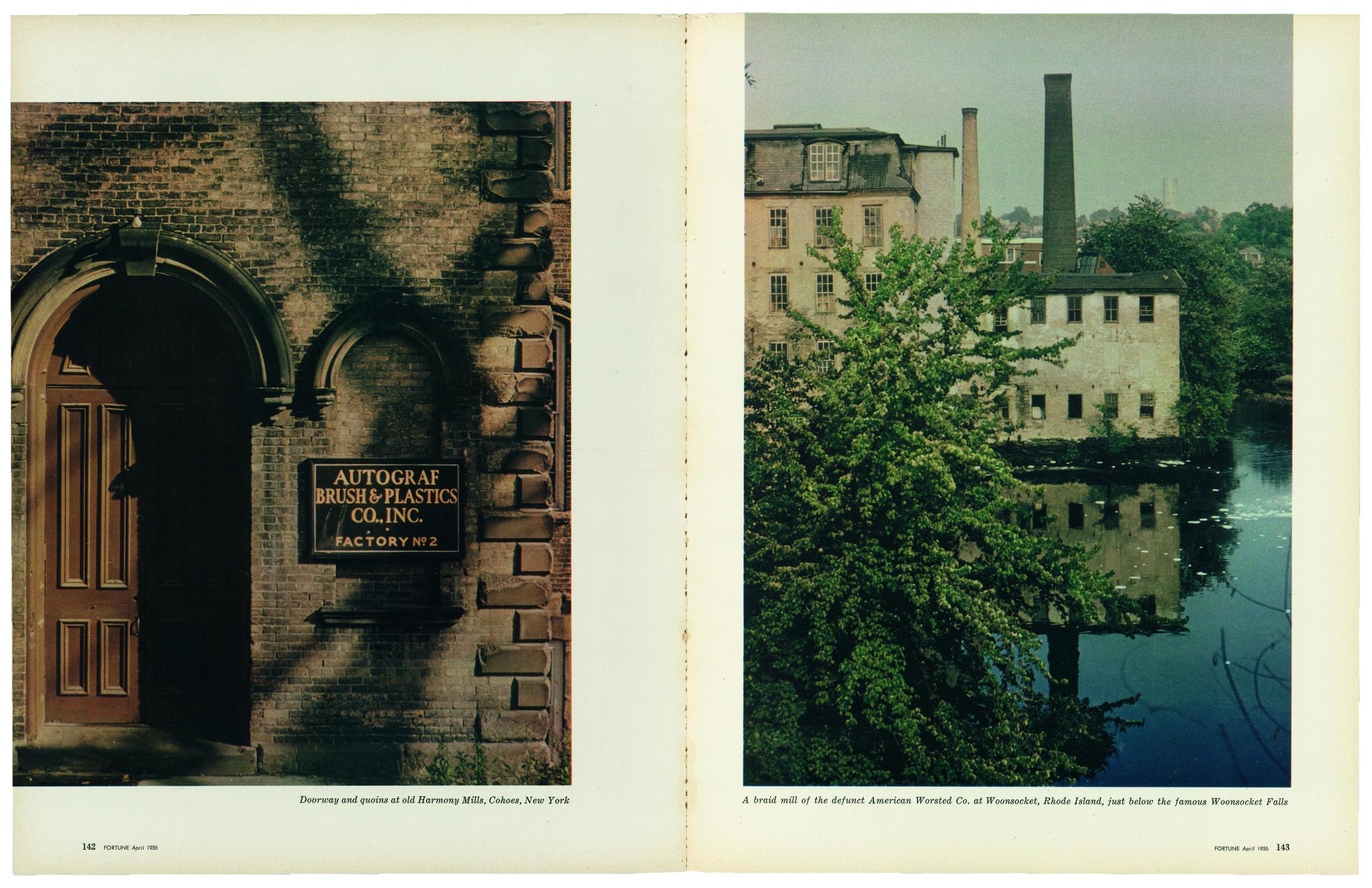

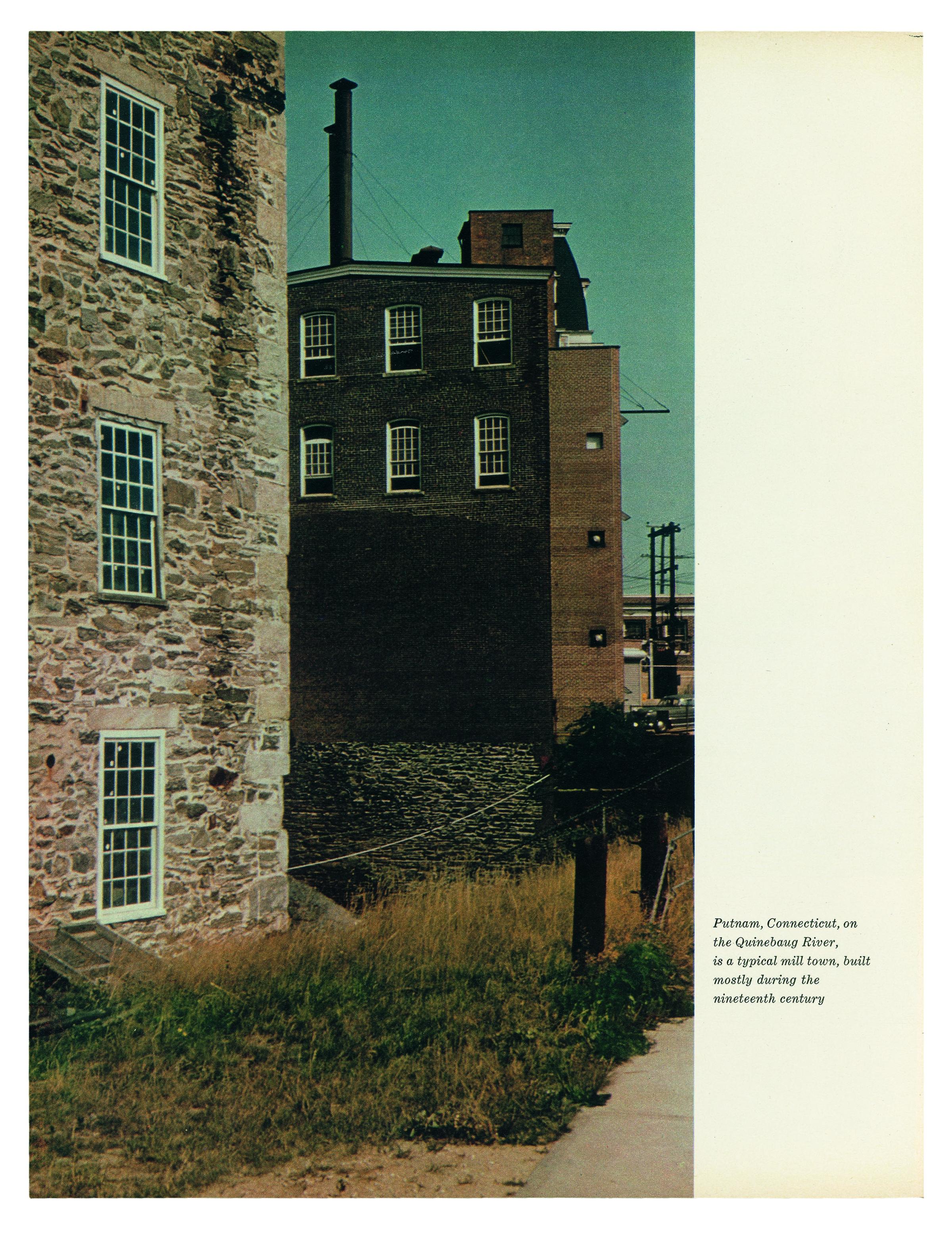

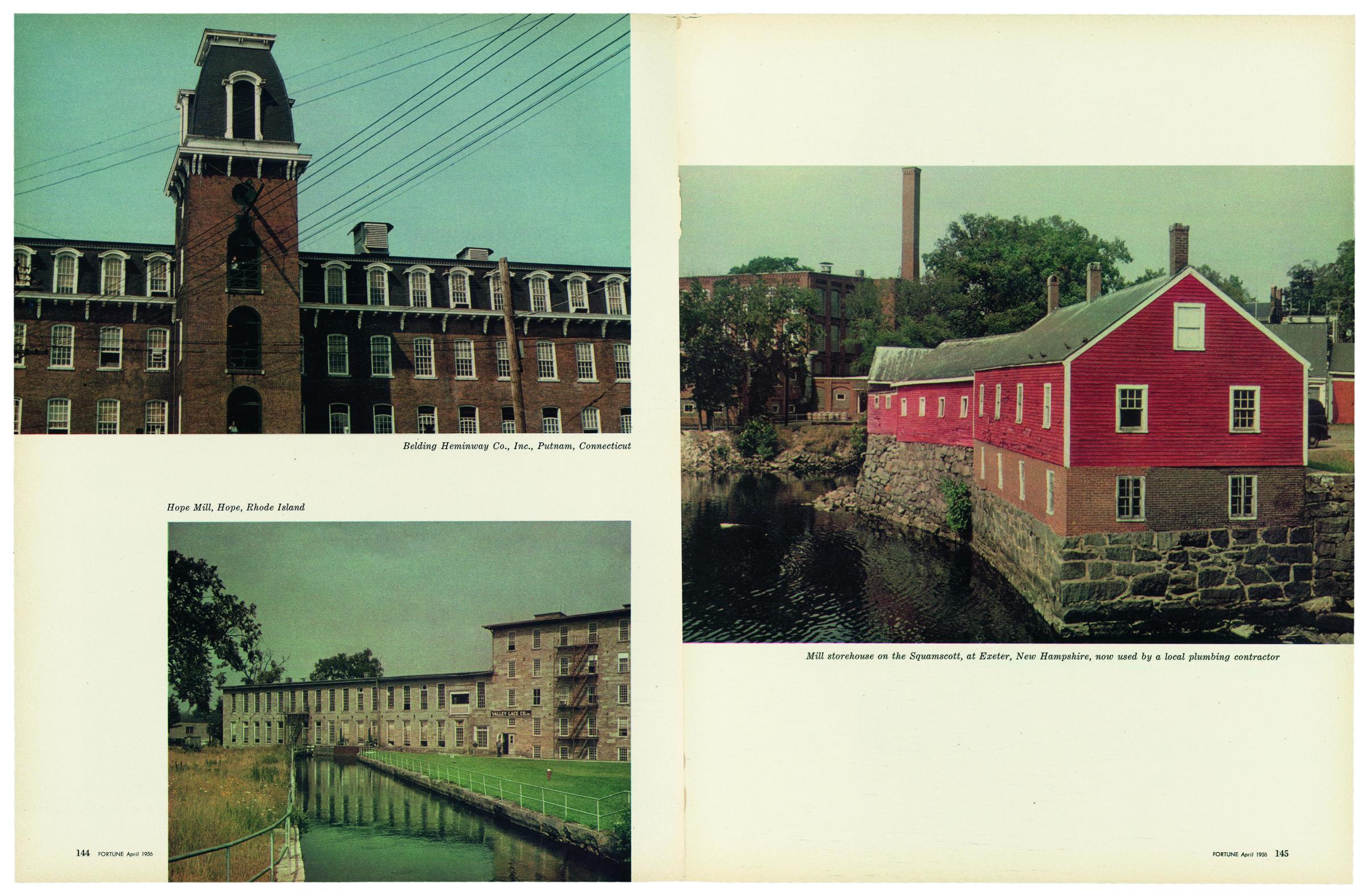

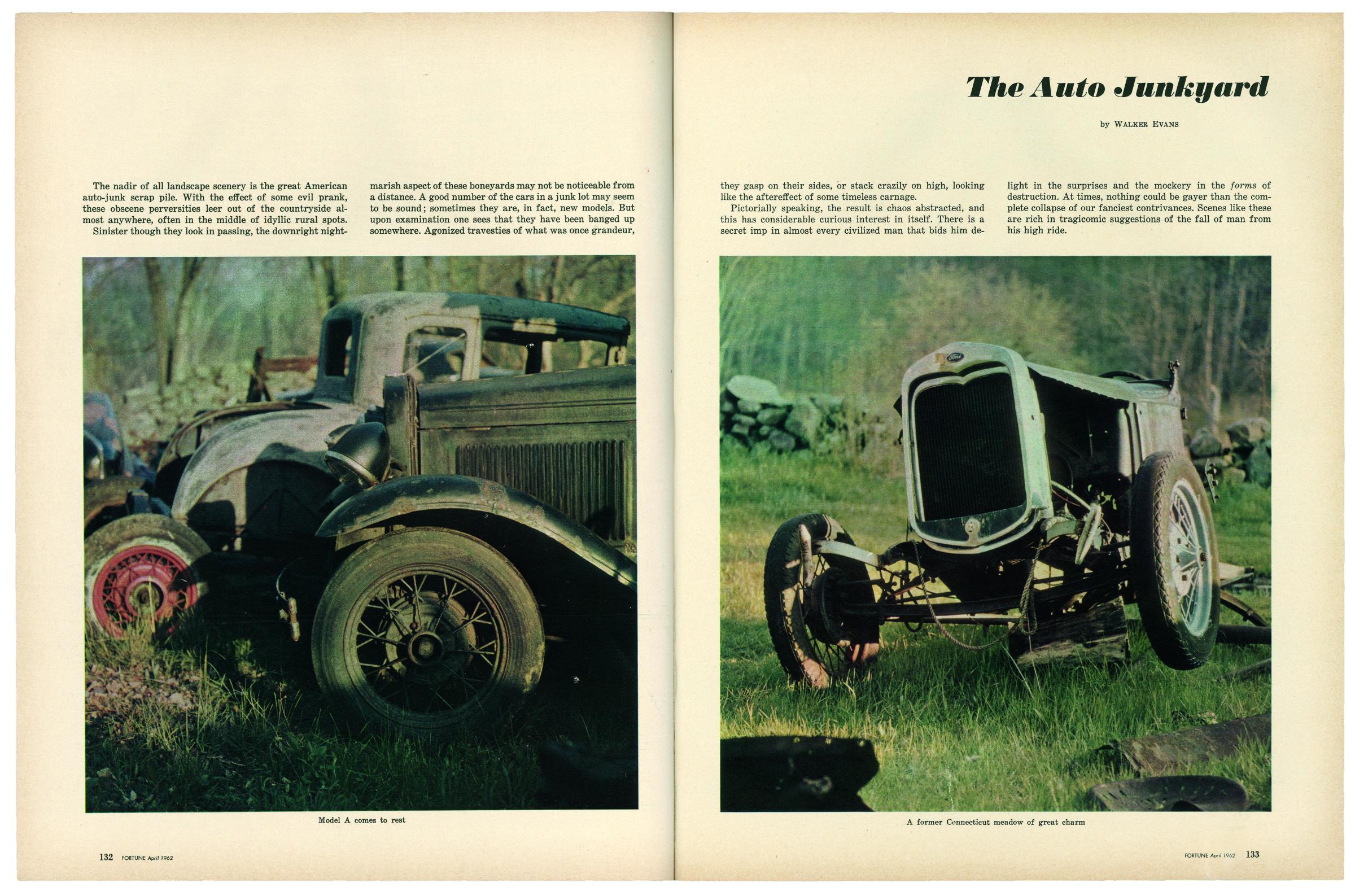

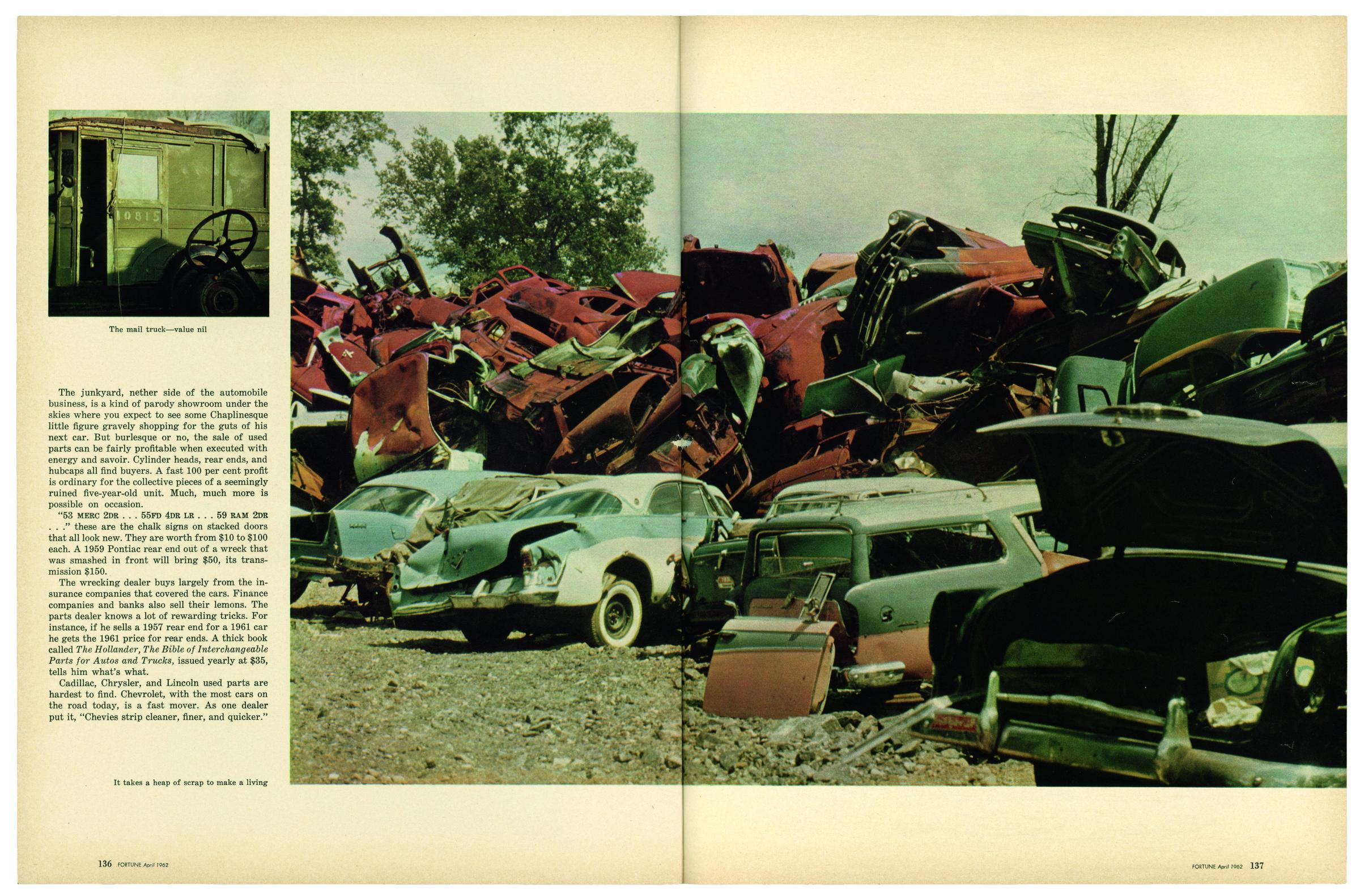

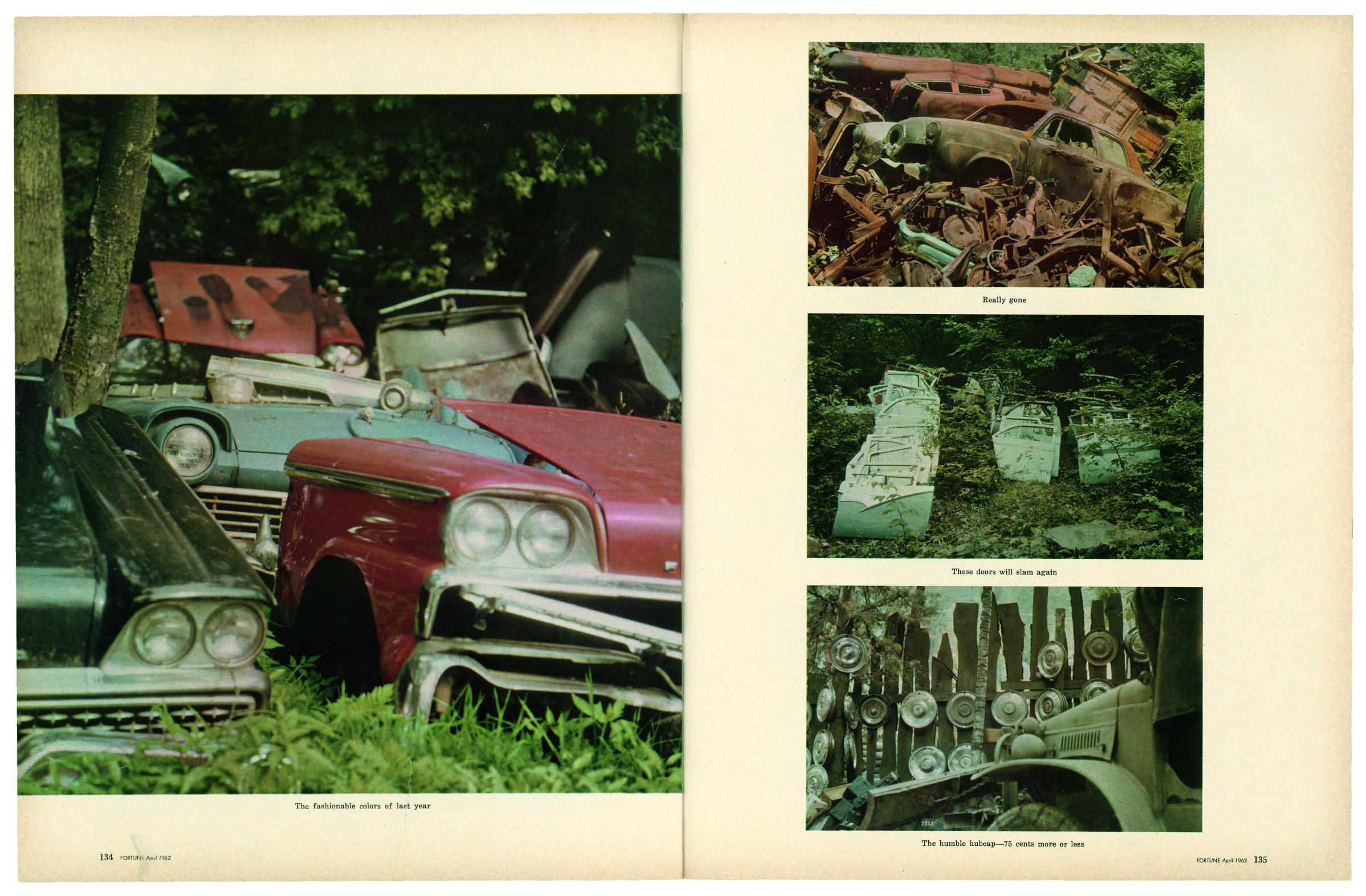

Fortune was one of the few magazines of its time to run color photography — a rarity Evans took full advantage of, producing multiple color portfolios during his tenure. In “These Dark Satanic Mills,” published in 1956, Evans devotes eight pages to what he called the “mellow Americana” of weathered mill buildings in the Northeast. In 1962, Evans returned to the region to document what he described in his accompanying copy as “the nadir of all landscape scenery,” the American junkyard. The rusted hulls of old Fords and Chryslers become a playground of auto-nostalgia through Evans’ lens, a “parody showroom under the skies.”

It’s impossible to overestimate the singularity of Evans’ role at Fortune, and at the other magazines where he contributed his time and talents, but a new book by David Campany (Steidl, 2014), explores this period of his photographic career — a period that has gone largely unnoticed due, in part, to the disposable nature of print. Exhaustively researched and meticulously edited, Walker Evans: The Magazine Work is a dense investigation not only of Evans’ work, but of the magazine industry at a crucial point in its development, when the worlds of art, design and documentary could cross, and a renegade with a singular vision could, quite literally, call the shots.

Krystal Grow is a contributor to TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram @kgreyscale.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com