The story is so improbable, so marvelous, that it feels more like the remnant of a dream, or a half-remembered myth, rather than something that unfolded within living memory. . . .

September 12, 1940. A warm afternoon in Dordogne, in southwestern France. Four boys and their dog, Robot, walk along a ridge covered with pine, oak and blackberry brambles. When Robot begins digging near a hole beside a downed tree, the boys tell each other that this might be the entrance to a legendary tunnel running beneath the Vézère River, leading to a lost treasure in the woods of Montignac. The youngsters begin to dig, widening the hole, removing rocks—until they’ve made an opening large enough for each to slip through, one by one. They slide down into the earth—and emerge into a dark chamber beneath the ground.

They have discovered not merely another place, but another time.

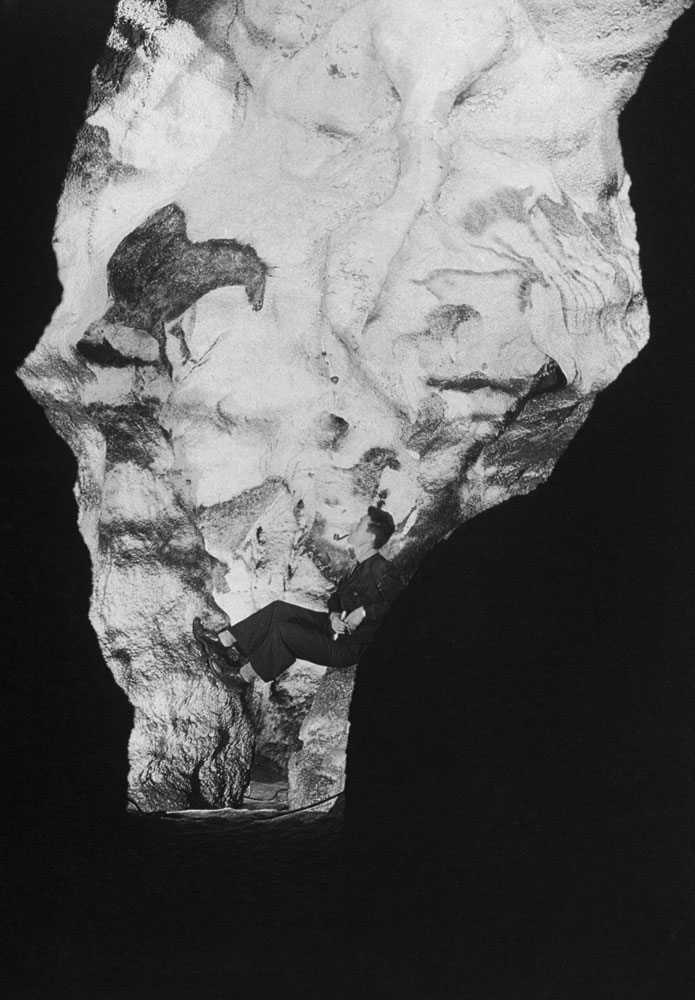

In the cool dark beneath the sunlit world above, the boys found themselves in “a Versailles of prehistory”—a vast series of caves, today collectively known as Lascaux, covered with wall paintings that, by some estimates, are close to 20,000 years old. In 1947, LIFE magazine’s Ralph Morse went to Lascaux, becoming the first professional photographer to document the breathtaking scenes. Now in his late-90s, Morse shared his memories of that time and place with LIFE.com, recalling what it was like to encounter the strikingly lifelike, gorgeous handiwork of a long-vanished people: the Cro-Magnon.

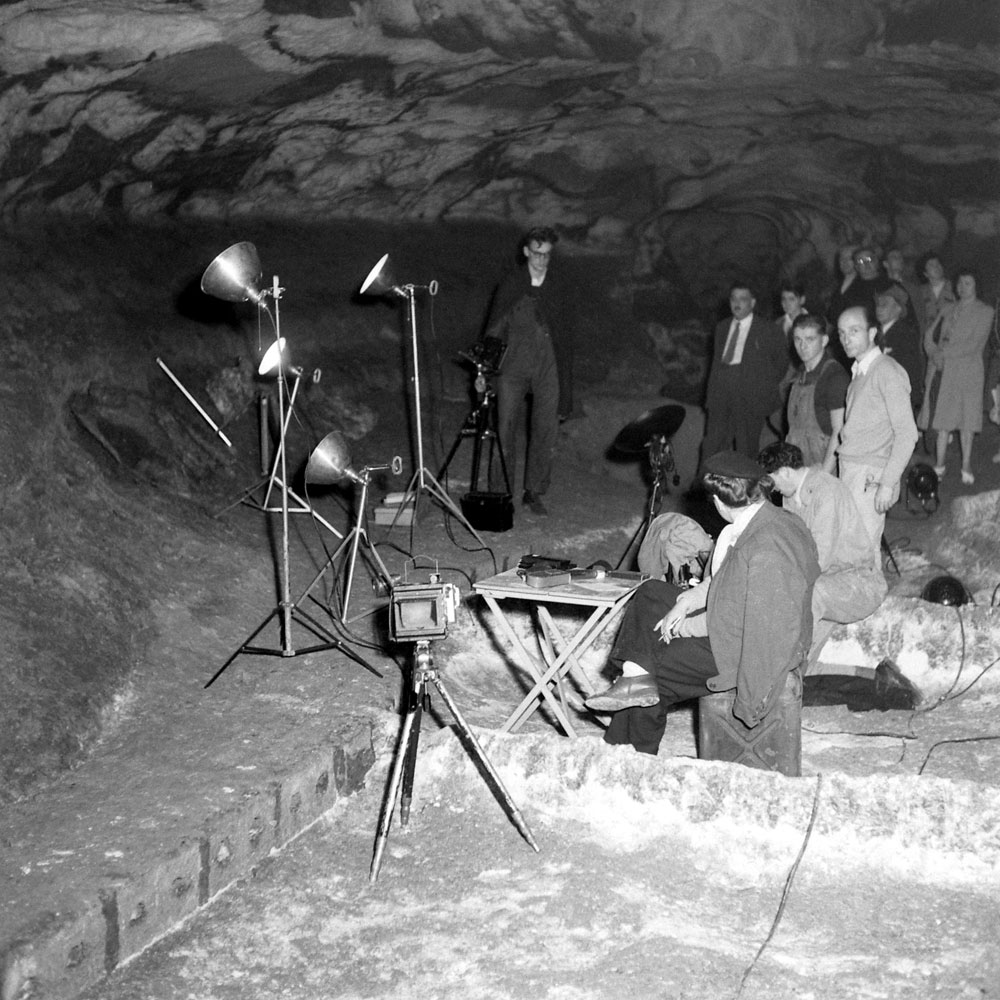

“LIFE re-opened its Paris bureau after the second World War ended, in the same offices we rented before the war,” Morse recalled. “One day, we get a message from New York about some cave that people have been talking about. We do a little research, and find out that even though the cave was discovered a few years before, no one’s ever photographed the paintings inside. We know that the first thing we need is a generator to power our lights, but getting a generator anywhere after the war was almost impossible. We had to have people in London ship one over.

“The first sight of those paintings was simply unbelievable,” he said. “I was amazed at how the colors held up after thousands of years—like they were painted the day before. Most people don’t realize how huge some of the paintings are. There are pictures of animals there that are ten, fifteen feet long.”

“But it wasn’t a comfortable assignment,” Morse remembered. “It wasn’t a refined setting. It was a dungarees-and-sweatshirt job. When we first went down, there were no steps. You slid down on your rear end on a piece of wood or the bare earth.”

The Cro-Magnon (from the French, “Abri de Crô-Magnon,” after a cave where remains were first found in 1868) were evidently far from the cartoonish, savage brutes of popular myth. In fact, over the past 150 years, scientists and artists alike have developed a complex, nuanced view of these early modern humans. In his most beautiful book, The Colossus of Maroussi (1941), the writer Henry Miller asserted: “I believe that Cro-Magnon settled here [in the Dordogne region] because he was extremely intelligent and had a highly developed sense of beauty.”

Miller, who was also an accomplished painter, went on: “I believe that in Cro-Magnons the religious sense was already highly developed and that it flourished here even if he lived like an animal in the depths of caves.”

One of the central challenges faced by those studying the many, many images in Lascaux’s numerous chambers (the Great Hall of the Bulls, the Chamber of Felines, etc.) is assigning dates to images painted in what can only be called different “styles.” Were the images at Lascaux painted by Cro-Magnon artists across scores of generations? Were they painted by hunters paying tribute to prey? By shamans hoping to harness, or appease, the power of the natural world? Theories abound; but no one really knows.

“We were the first people to light up the paintings so that we could see those beautiful colors on the wall,” Morse said. “Some people had been down there before us—but with flashlights, at best. We were the first to haul in professional gear and bring those spectacular paintings to life. It was a challenging project—getting the generator, running wires down into the cave, lowering all the camera equipment down on ropes. But once the lights were turned on. . . . Wow!”

“In [Cro-Magnon man’s] most expert period,” LIFE noted in its Feb. 24, 1947 issue (in which a handful of Morse’s photos first appeared), “his apparatus included engraving and scraping tools, a stone or bone palette and probably brushes made of bundled split reeds. He ground colored earth for his rich reds and yellows, used charred bone or soot black for his dark shading and made green from manganese oxide. . . . For permanence, the finest pigments of civilized Europe have never rivaled these crude materials.”

In 1948, a year after Morse’s pioneering photographic work, Lascaux was opened to the public. But in 1963, the cave was closed after 15 short years when experts determined that carbon dioxide from the breath of thousands of visitors, as well as spores and other post-Ice Age contaminants tramped in from above ground, were damaging the paintings. Today, only a handful of people are allowed inside Lascaux for a few days each year to monitor damage (a mysterious, encroaching mold is the latest culprit) while they work to keep the magnificent paintings adorning the walls from going the way of their creators, and vanishing entirely.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com