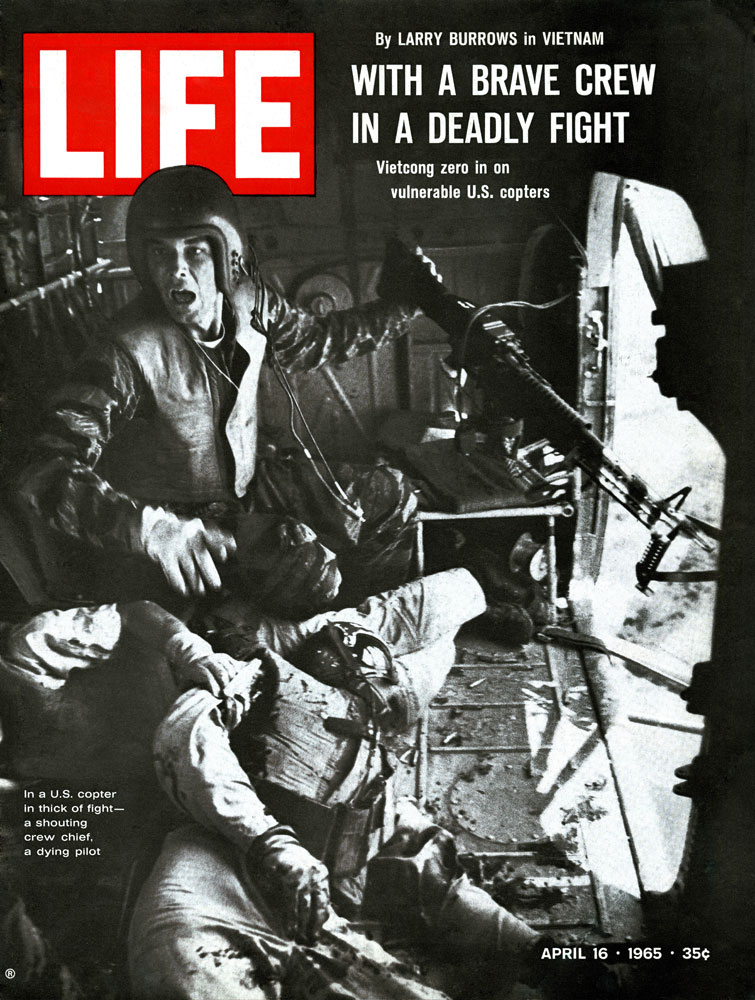

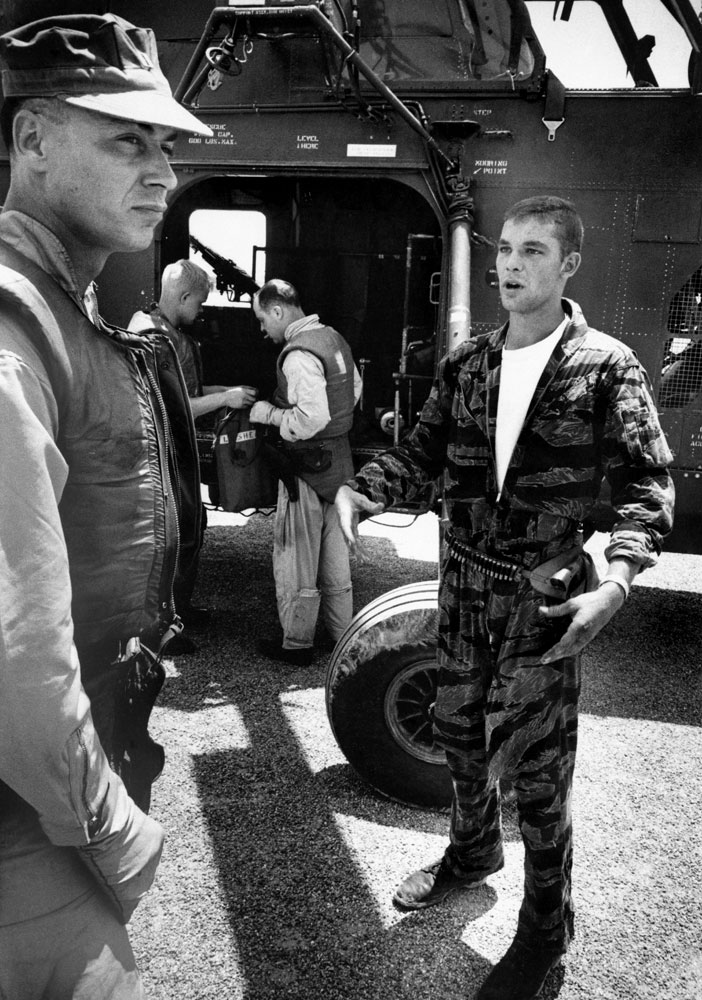

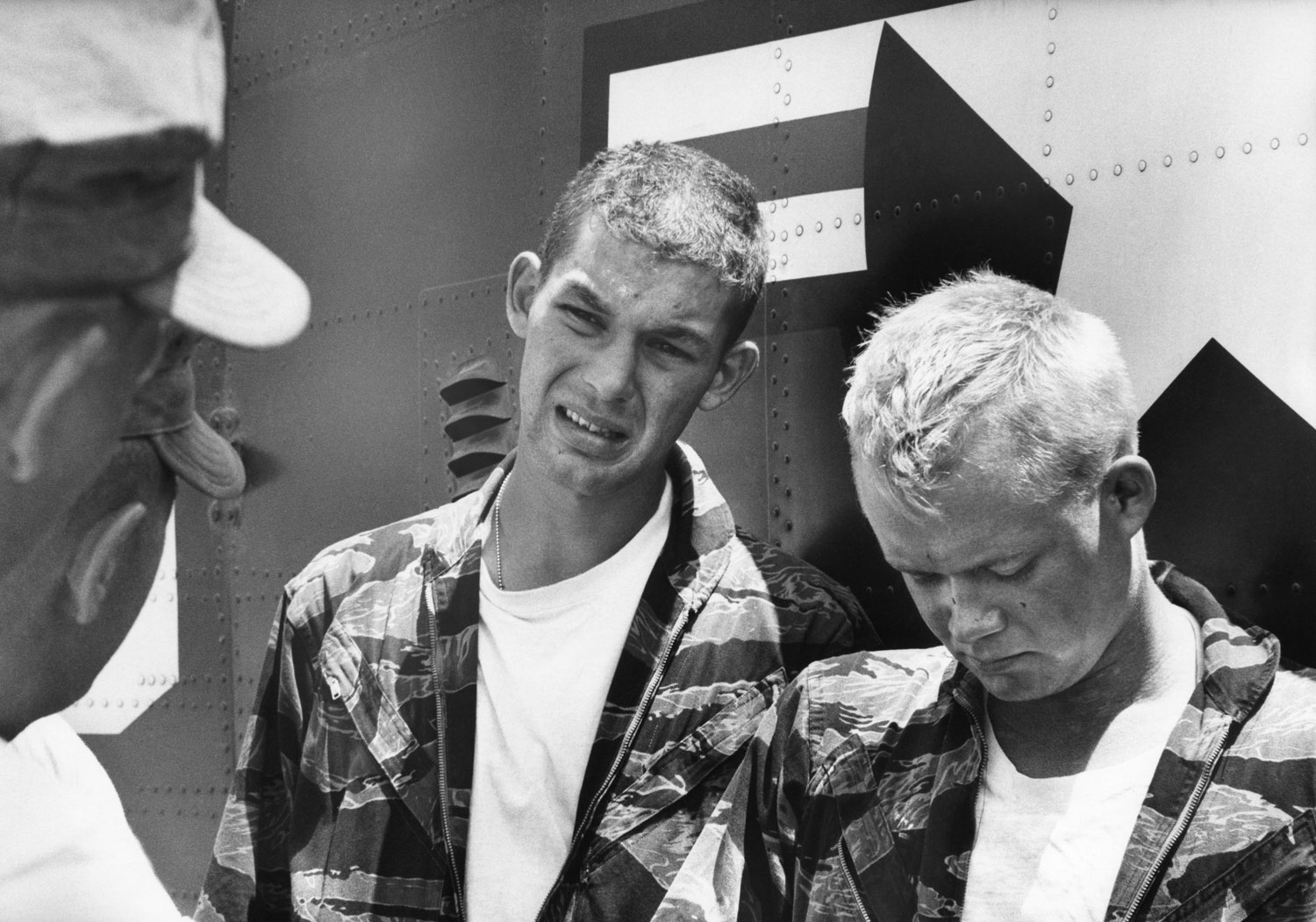

In the spring of 1965, within weeks of 3,500 American Marines arriving in Vietnam, a 39-year-old Briton named Larry Burrows began work on a feature for LIFE magazine, chronicling the day-to-day experience of U.S. troops on the ground—and in the air—in the midst of the rapidly widening war. The photographs in this gallery focus on a calamitous March 31, 1965, helicopter mission; Burrows’ “report from Da Nang,” featuring his pictures and his personal account of the harrowing operation, was published two weeks later as a now-famous cover story in the April 16, 1965, issue of LIFE.

Over the decades, of course, LIFE published dozens of photo essays by some of the 20th century’s greatest photographers. Very few of those essays, however, managed to combine raw intensity and technical brilliance to such powerful effect as “One Ride With Yankee Papa 13″—universally regarded as one of the greatest photographic documents to emerge from the war in Vietnam.

Here, LIFE.com presents Burrows’ seminal photo essay in its entirety: all of the photos that appeared in LIFE are here.

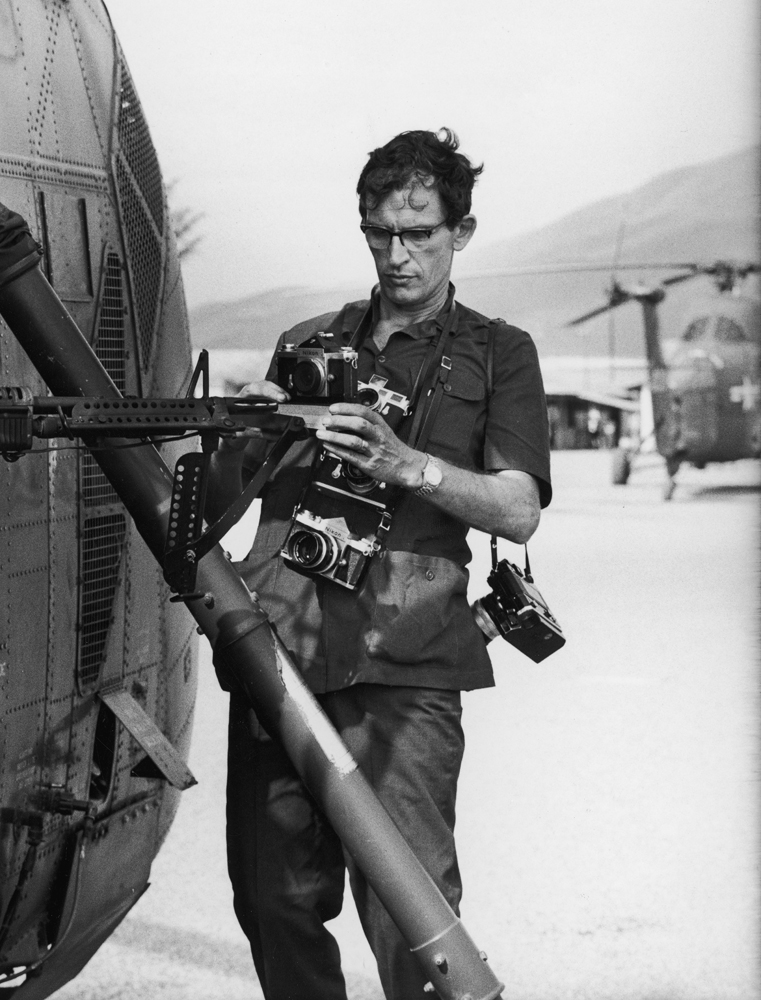

(Left: In a picture from the article, Burrows mounts a camera to a special rig attached to an M-60 machine gun in helicopter YP13 — a.k.a., “Yankee Papa 13.” At the end of this gallery, there are three previously unpublished photographs from Burrows’ 1965 assignment.]

Burrows, LIFE informed its readers, “had been covering the war in Vietnam since 1962 and had flown on scores of helicopter combat missions. On this day he would be riding in [21-year-old crew chief James] Farley’s machine—and both were wondering whether the mission would be a no-contact milk run or whether, as had been increasingly the case in recent weeks, the Vietcong would be ready and waiting with .30-caliber machine guns. In a very few minutes Farley and Burrows had their answer.”

The following paragraphs—lifted directly from LIFE—illustrate the vivid, visceral writing that accompanied Burrows’ astonishing images, including Burrows’ own words, transcribed from an audio recording made shortly after the 1965 mission:

“The Vietcong dug in along the tree line, were just waiting for us to come into the landing zone,” Burrows reported. “We were all like sitting ducks and their raking crossfire was murderous. Over the intercom system one pilot radioed Colonel Ewers, who was in the lead ship: ‘Colonel! We’re being hit.’ Back came the reply: ‘We’re all being hit. If your plane is flyable, press on.’

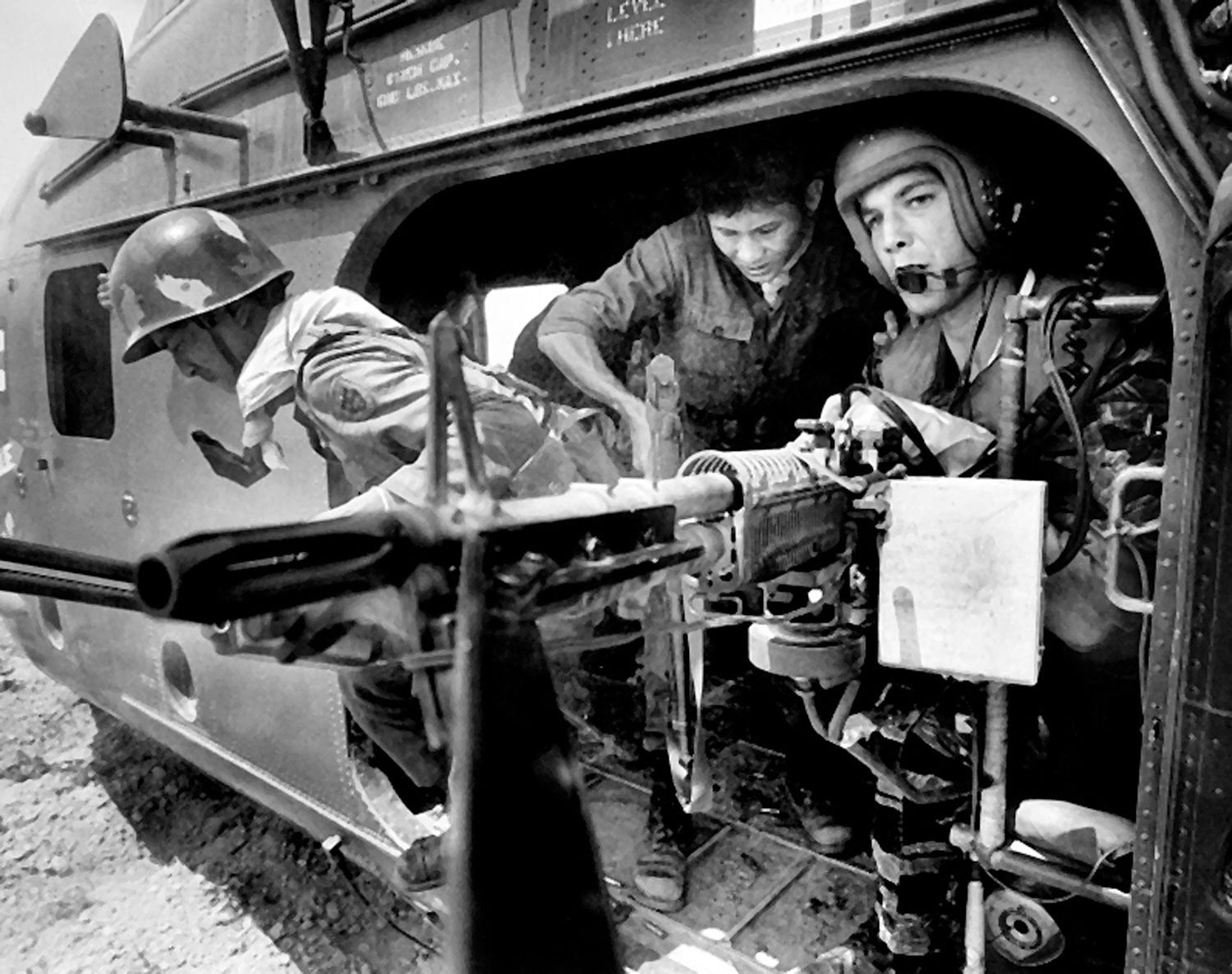

“We did,” Burrows continued, “hurrying back to a pickup point for another load of troops. On our next approach to the landing zone, our pilot, Capt. Peter Vogel, spotted Yankee Papa 3 down on the ground. Its engine was still on and the rotors turning, but the ship was obviously in trouble. ‘Why don’t they lift off?’ Vogel muttered over the intercom. Then he set down our ship nearby to see what the trouble was.

“[Twenty-year-old gunner, Pfc. Wayne] Hoilien was pouring machine-gun fire at a second V.C. gun position at the tree line to our left. Bullet holes had ripped both left and right of his seat. The plexiglass had been shot out of the cockpit and one V.C. bullet had nicked our pilot’s neck. Our radio and instruments were out of commission. We climbed and climbed fast the hell out of there. Hoilien was still firing gunbursts at the tree line.”

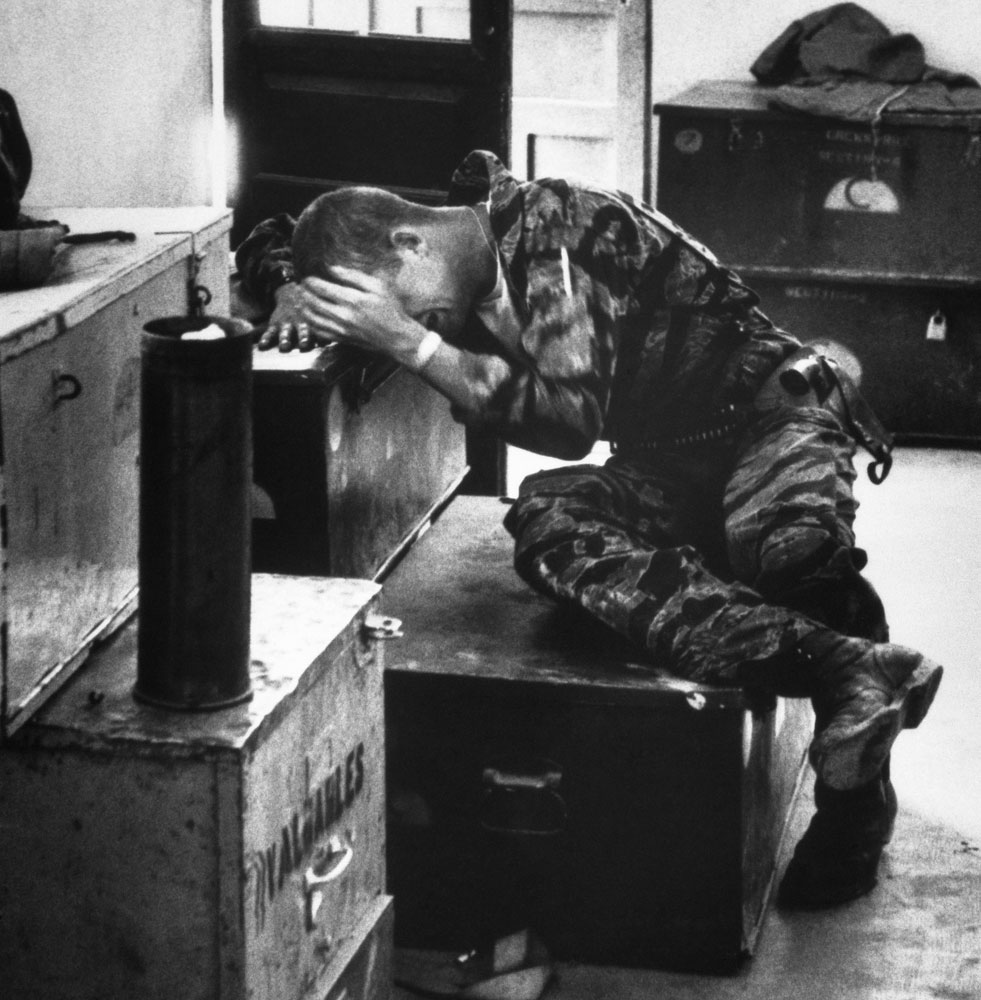

Not until YP13 pulled away and out of range of enemy fire were Farley and Hoilien able to leave their guns and give medical attention to the two wounded men from YP3. The co-pilot, 1st Lt. James Magel, was in bad shape. When Farley and Hoilien eased off his flak vest, they exposed a major wound just below his armpit. “Magel’s face registered pain,” Burrows reported, “and his lips moved slightly. But if he said anything it was drowned out by the noise of the copter. He looked pale and I wondered how long he could hold on. Farley began bandaging Magel’s wound. The wind from the doorway kept whipping the bandages across his face. Then blood started to come from his nose and mouth and a glazed look came into his eyes. Farley tried mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, but Magel was dead. Nobody said a word.”

In his searing, deeply sympathetic portrait of young men fighting for their lives at the very moment America is ramping up its involvement in Southeast Asia, Larry Burrows’ work anticipates the scope and the dire, lethal arc of the entire war in Vietnam.

Six years after “Yankee Papa 13” ran in LIFE, Burrows was killed, along with three other journalists—Henri Huet, Kent Potter and Keisaburo Shimamoto—when a helicopter in which they were flying was shot down over Laos in February, 1971. He was 44 years old.

Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE.com

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com