Today, when a photograph of Barack Obama or a Kardashian or Lionel Messi — or, for that matter, a photograph of any of us — can be seen by literally millions of people within moments of being made, it’s easy to take the ubiquity of portraits of the famous, the powerful and even the notorious for granted. The dissemination and consumption of pictures — photographs, of course, but also caricatures, posters, graffiti and all manner of other still, static images — is now so all-pervading in so many cultures that it’s easy to forget that, not too long ago, one person’s face being recognized on a global scale was a rare and striking phenomenon.

Four or five decades ago, the number of public figures whose faces were familiar to people on virtually every continent was far, far smaller than it is today. Muhammad Ali, of course. Che Guevara. John F. Kennedy. Pelé. Marilyn Monroe. More than a handful, for sure — but far from the countless faces of the famous, the notorious and the ubiquitous with which we’re bombarded today. Travel back another decade or two, and not only is the number of globally recognized figures even smaller, but the means of transmitting, sharing or otherwise displaying those famous faces are seriously limited. It’s a wonder, sometimes, that any major figure of the mid-20th century ever made a splash, visually speaking, outside of his or her own pond.

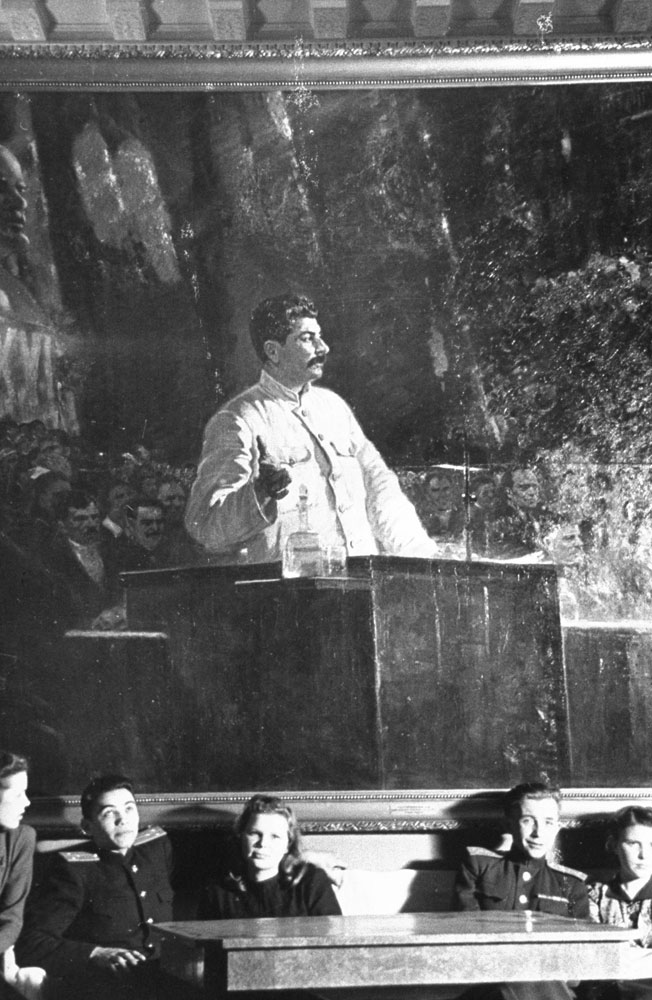

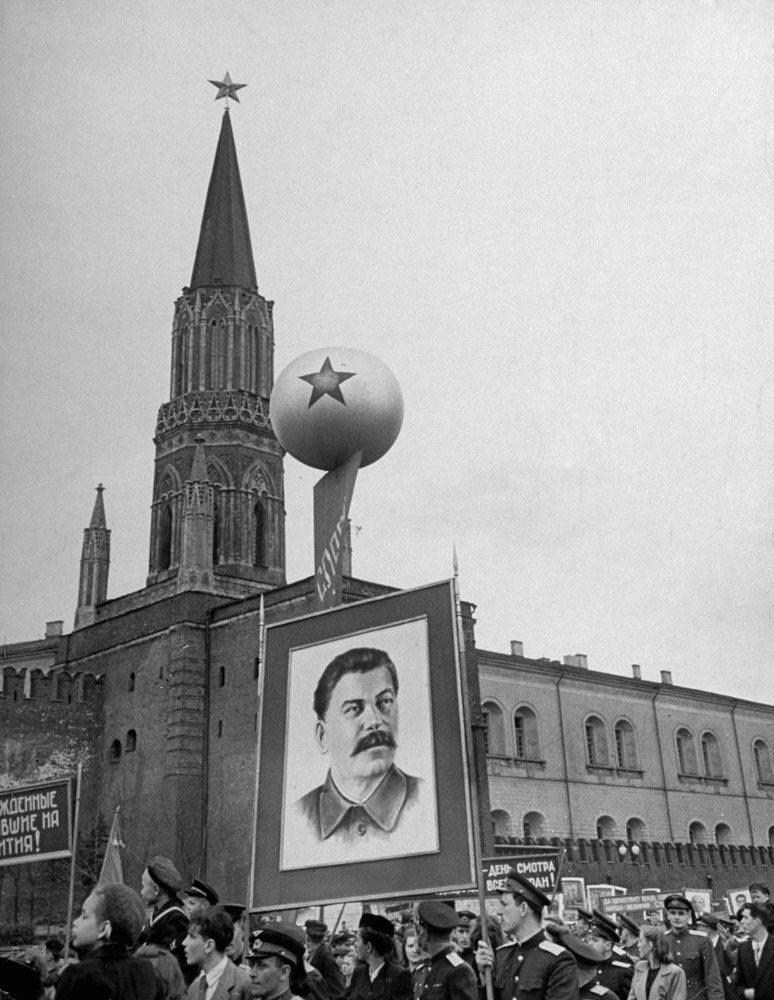

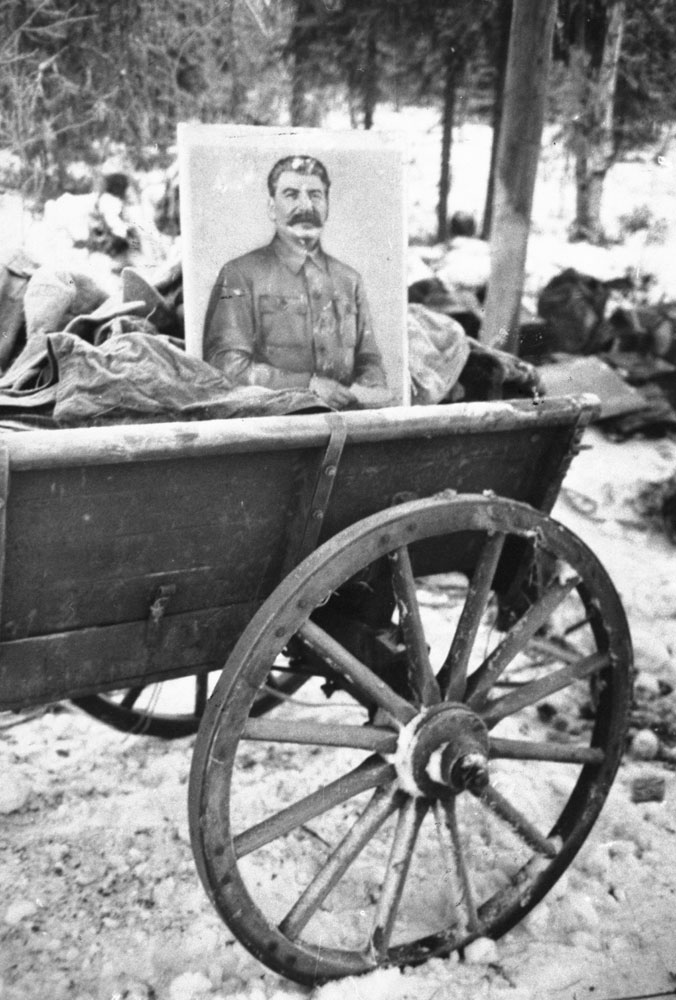

Which brings us to Stalin. Here, LIFE looks back at the way one of the most immediately recognizable — and infamous — figures of the past 100 years was pictured in countries around the world at the very height of his power.

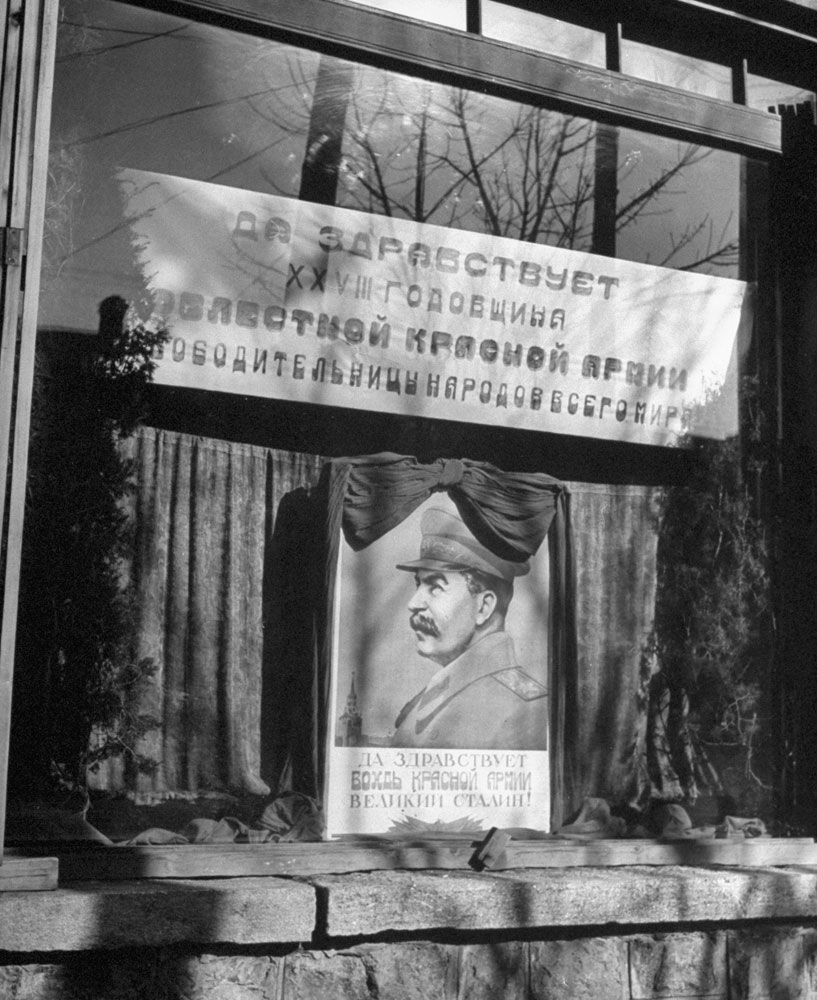

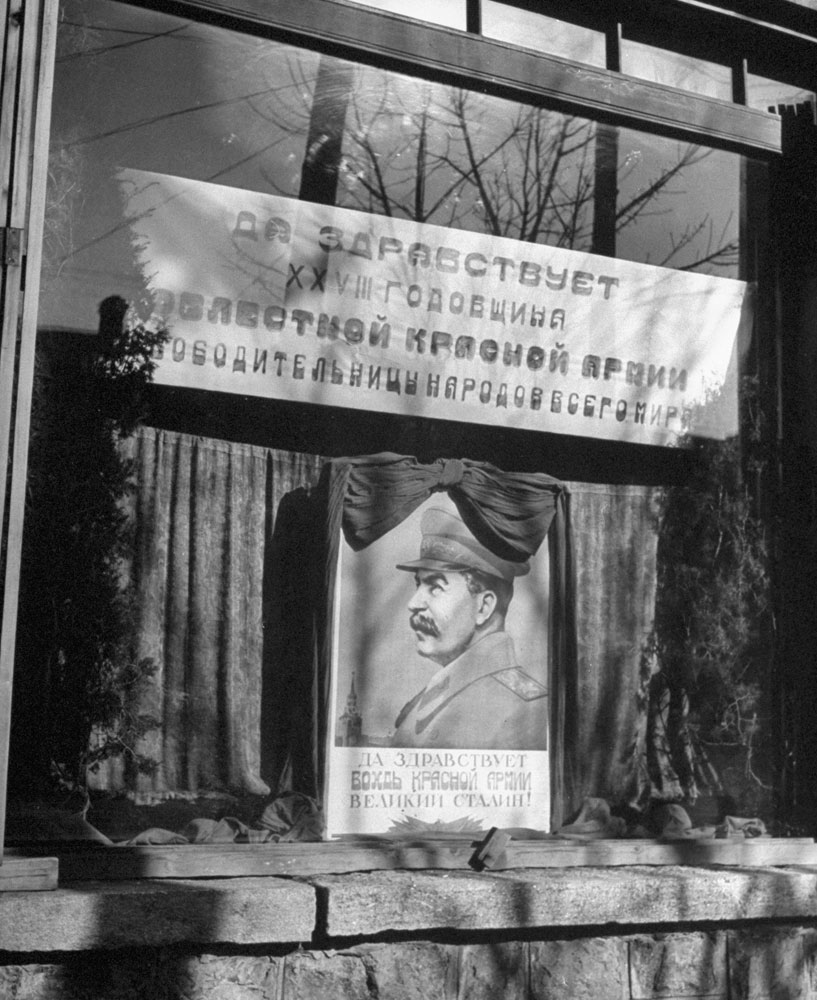

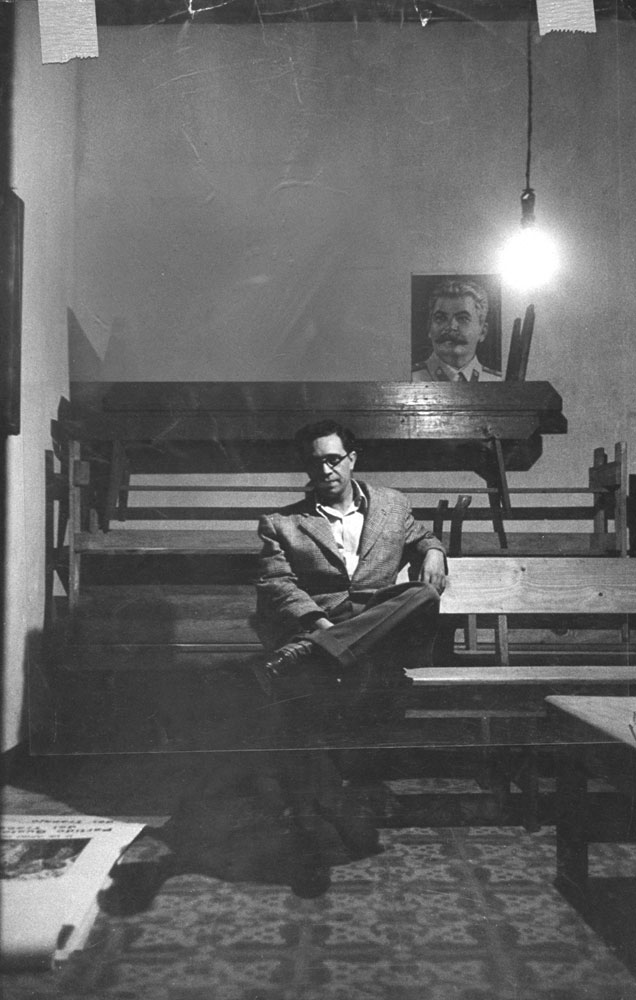

Far from the dizzying speed with which so much era-defining imagery travels today, whether it’s pictures of government-sponsored slaughter in Syria or the final embrace of a couple buried alive in a disaster, looking at these images of Stalin (left: a portrait by LIFE’s Margaret Bourke-White) one senses that his visual journey around the world was far more gradual, more deliberate, more akin to a glacier than a beam of light, or a series of one and zeroes flashing across the Internet.

But the plodding nature of his portrait’s travels, from Russia to Finland to China to Guatemala and beyond, hardly lessens the power of its prevalence. In fact, if anything, the slow, steady creep of Stalin’s visage around the planet 60 and 70 years ago feels, in some ways, more remarkable than the instantaneous, impossibly varied juggernaut of pictures that we encounter each day. There is something at once terribly gloomy and profoundly, clinically impressive in how widespread Stalin’s portrait became — as if one is mapping, in the face of its most prominent carrier, the path of a disease seen there, and there, and there. . . .

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com