When Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space in April 1961, a stunned America had two questions: How could this happen? and When is one of our guys going up there? Weeks later, on May 5, 1961, the second question was emphatically answered when 37-year-old Alan Shepard blasted off from Cape Canaveral on his own historic flight — a feat that made the New Hampshire native the first American in space and marked a major United States triumph in the Space Race.

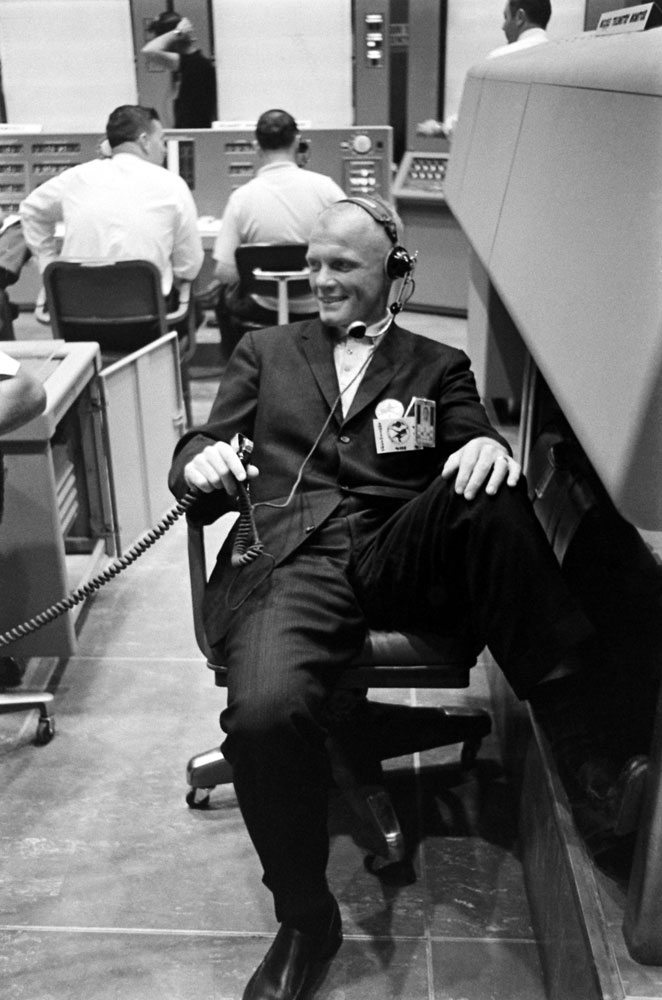

Here, on the anniversary of Shepard’s historic flight, LIFE.com presents pictures, the vast majority of them by LIFE’s Ralph Morse (dubbed “the 8th Mercury astronaut” by John Glenn), along with Morse’s own memories of that amazing era, and those magnificent young men in their flying machines.

Of the three astronauts chosen as candidates for America’s first manned space flight, only one could or would ultimately star in what LIFE magazine, in March 1961, called the “violent, historic event. . . . Some time this spring, either John Glenn or Virgil Grissom or Alan Shepard will crawl into a small capsule on top of a Redstone rocket and wait for the most awesome journey that man has ever taken.”

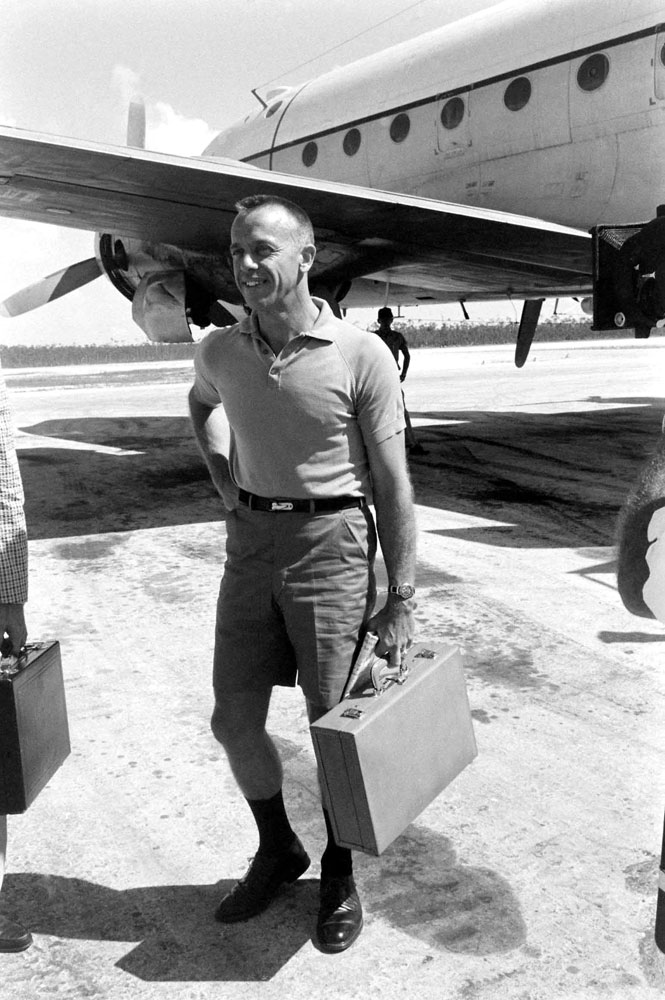

Shepard was a Navy test pilot who had logged more than 8,000 hours flying before joining the space program. He was also, LIFE assured its readers, “a cool customer. . . . The tallest (5′ 11″) of the astronauts, Shepard holds his wiry frame with a loose grace and dresses, even in sports clothes, with a crisp immaculateness that reflects his Naval Academy training.” For his part, Ralph Morse recalls that Shepard “was much slower at making friendships than Glenn or Carpenter or the others. But when Alan became your friend, he was a great friend. He was very, very smart, and personable when you got to know him. And like all of those guys, he was solid as hell. A perfect choice, really, for the first flight.”

After NASA announced that he was the one tapped for the first space flight, Shepard found himself in the heart of an unprecedented media storm. (NASA had delayed the announcement of who would wear the uneasy mantle of “the first American in space” for so long for that very reason — to try and keep the spotlight off of one astronaut for as long as possible.)

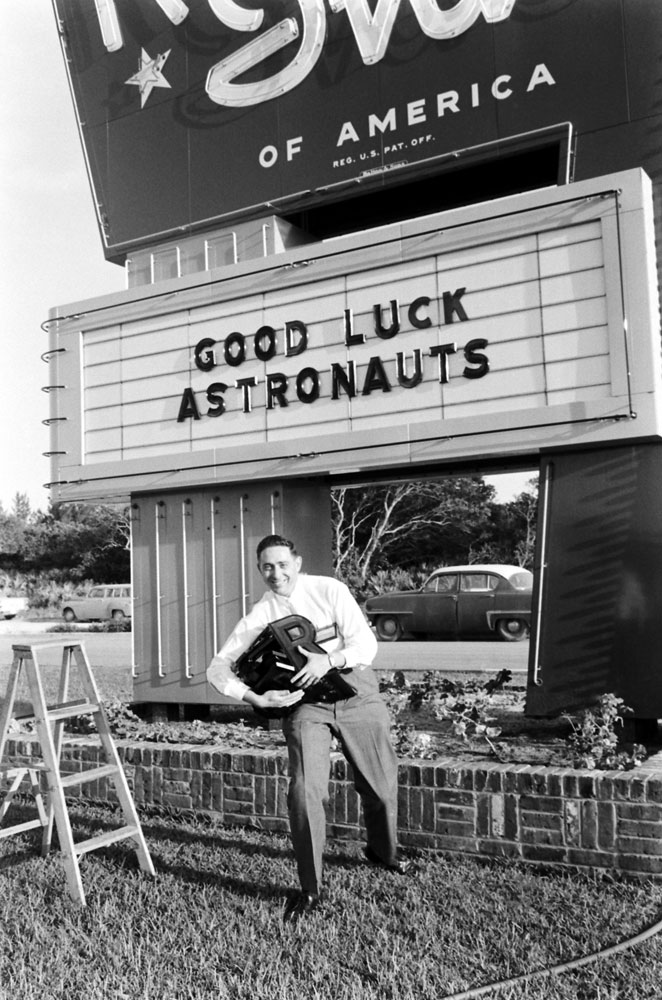

“These guys couldn’t go anywhere without being accosted,” Morse says. “They all had their own bungalows at the Cape [Canaveral], but there was no real privacy, especially as the launch date approached and people were getting worked up about the flight. Autograph seekers, reporters wanting quotes, photographers wanting pictures — it was endless. I don’t know how Shepard and the rest handled it as well as they did. They were unflappable.”

For his own part, of all the talents he feels are necessary in order to enjoy a long, fruitful career as a photojournalist, Ralph Morse comes back again and again to two in particular: the ability to be prepared, and the ability to make and keep friendships. As a perfect illustration of this credo, he told LIFE.com a story about making some of the most famous pictures ever to emerge from the Project Mercury era (slides 7, 8 and 9 in the gallery).

“Early on, in 1959,,” Morse said, “I wanted a picture of the seven guys in their space suits. NASA said they wouldn’t allow it. Besides, they said, the seven would never wear the suits at the same time. Now, each of these suits cost a hundred grand — huge money back then — and, you know, ladies who read magazines want to see what a hundred thousand dollar dress looks like. But NASA always said no. Finally, one afternoon, Shorty Powers — a public affairs guy for NASA and, as far as I could tell, a frustrated astronaut — Shorty tells me, ‘Ralph, we decided to let you do that picture. Tonight. But you gotta get the guys together — and you gotta get the suits on them.’

“So here it is,” Morse continued, “mid-afternoon, and I only have a few hours to get all seven of these guys together, suit them up, and make the picture. But I’m going to make this picture happen because these guys are my friends. The suit men, the technicians who actually help put the astronauts into the suits, they’re my friends, too. Five of the astronauts are with me in Langley [Virginia], and they’re up for it. But Glenn and Grissom aren’t there. Glenn is home in Arlington, so I call him up. ‘John, I need you for a picture. Can you come down tonight?’ He says, ‘Of course.’ But Gus is in St. Louis. I call him up. ‘Gus, I need you.’ He says he can’t make it, he has plans that night, impossible.

“Now I really get to work on Grissom,” Morse says, laughing at the memory. “‘Gus, you’re an astronaut!” I yell at him. “Charter a plane, fly in. I take the picture, you fly back. We’ll charge it to LIFE.’ And that’s what he did. Gus flies in from St. Louis, all seven of these guys get in the suits — which took about an hour, because the things were brand new. Grissom flies back to St. Louis a few hours later, and I got my pictures. That’s friendship.”

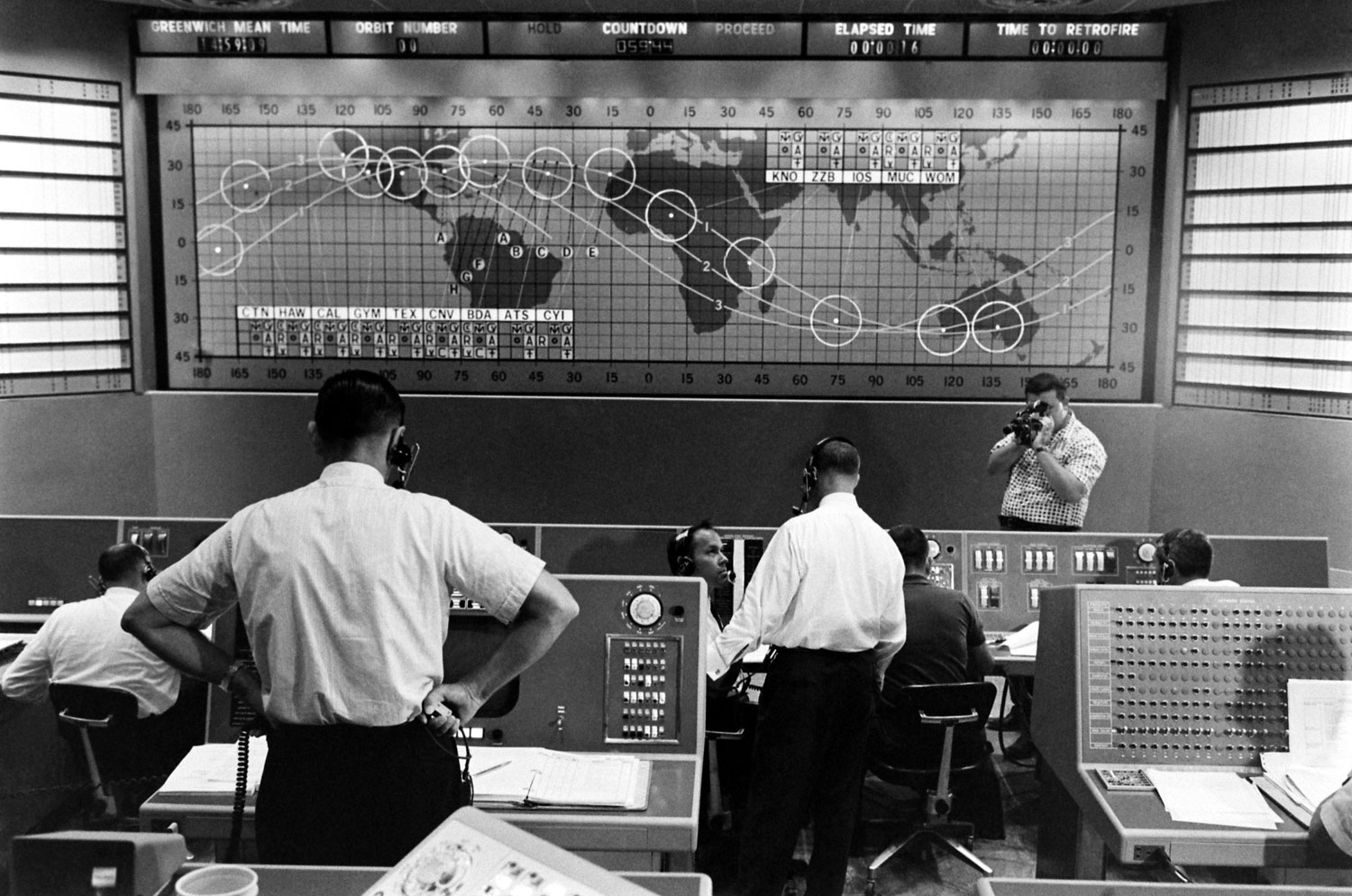

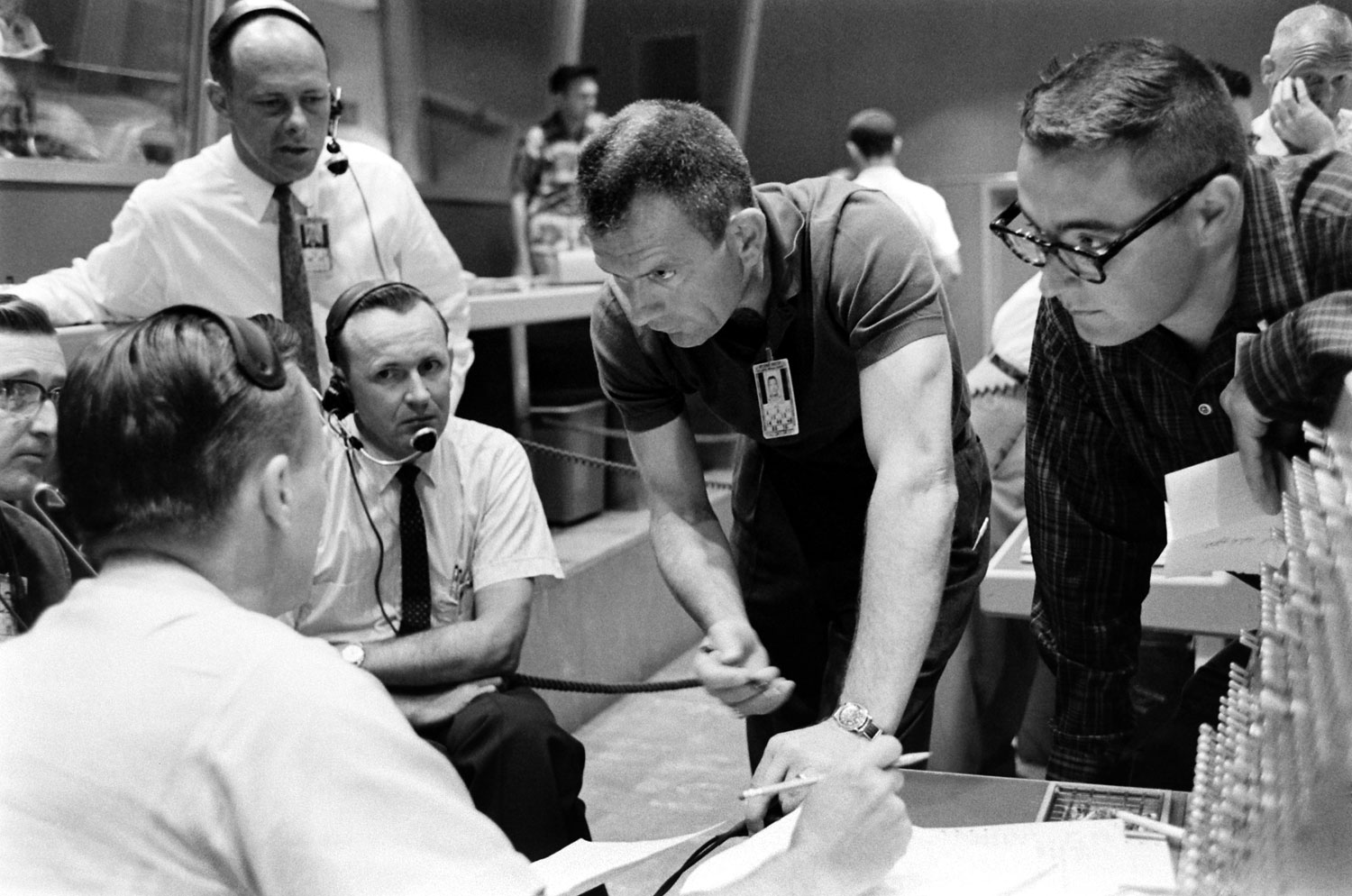

On Shepard’s launch day in May ’61, after he was secure in the capsule, the flight was delayed for four hours, partly due to weather — clouds would obscure filming of the launch — and because last-minute radio-system repairs were required. Cramped, uncomfortable (at one point, unable to exit the capsule, he urinated in his flight suit) and increasingly anxious to get underway, Shepard finally uttered one of the most famous communications in NASA history. Addressing the engineers and technicians at launch control, he asked, “Why don’t you fix your little problem and light this candle?”

While his flight proved a huge boost for NASA, Shepard did not, in fact, orbit the Earth. His was a “sub-orbital” trajectory, meaning he and his Freedom 7 craft reached a maximum altitude of around 115 miles — but did not come close to a true circling of the globe.

A few weeks later, President Kennedy famously declared: “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space. . . . But in a very real sense, it will not be one man going to the moon — if we make this judgment affirmatively, it will be an entire nation.”

[Read Jeffrey Kluger’s tribute to Neil Armstrong.]

Shepard was hardly one to rest on his laurels, and his NASA career included many more triumphs after his Freedom 7 flight. In 1971, as commander on Apollo 14, he became one of the handful of humans to walk on the moon — and (thus far) the only person in history to smuggle a golf club head aboard a space craft, attach it to a lunar-sample scoop handle and tee off on the lunar surface. One of his drives, he later joked, traveled for “miles and miles and miles.”

Alan Shepard, who retired as a U.S. Navy Rear Admiral, died in 1998. He was 74.

— Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE.com

![Alan B. Shepard [& Family]](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/50571230.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com