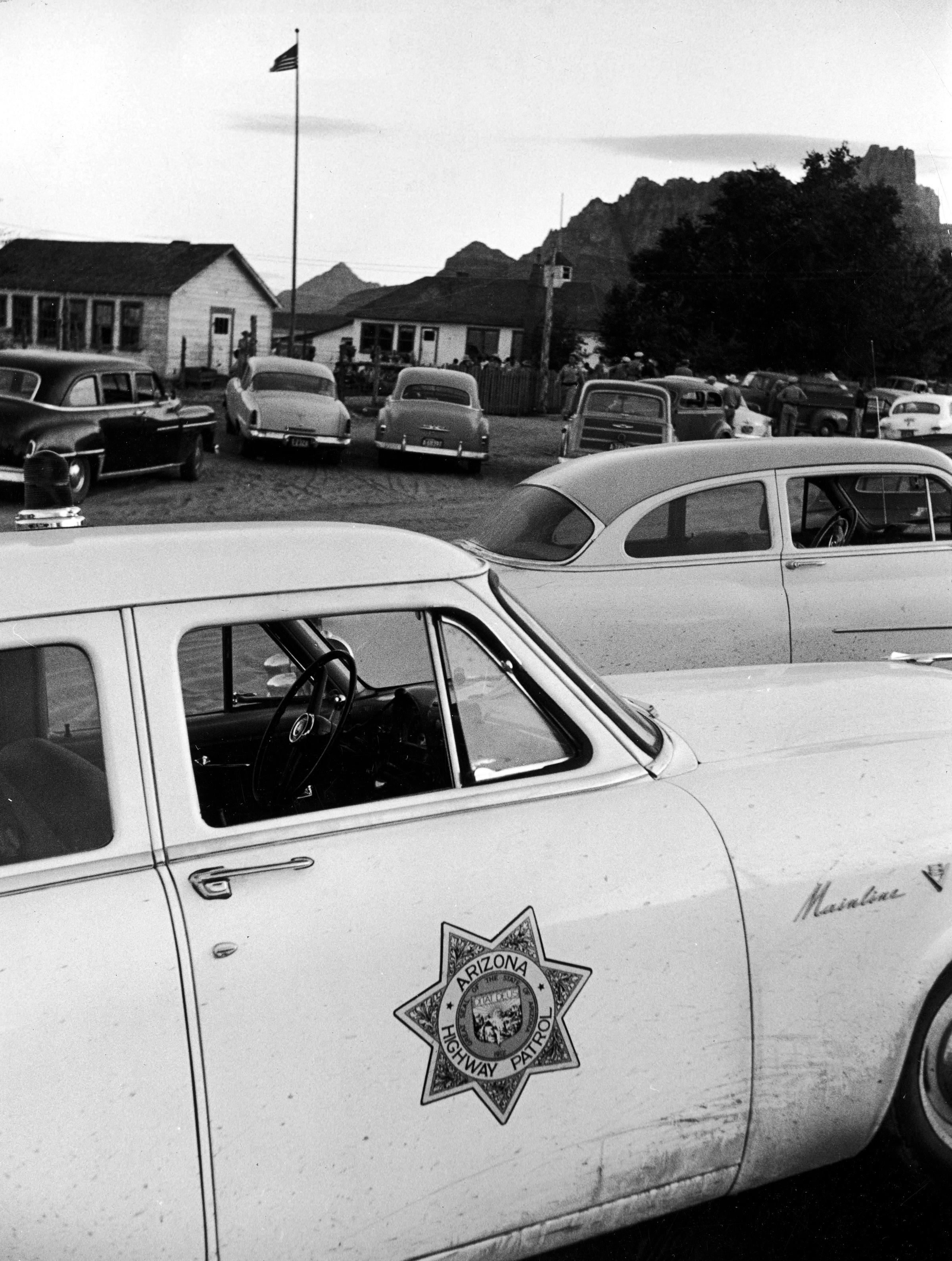

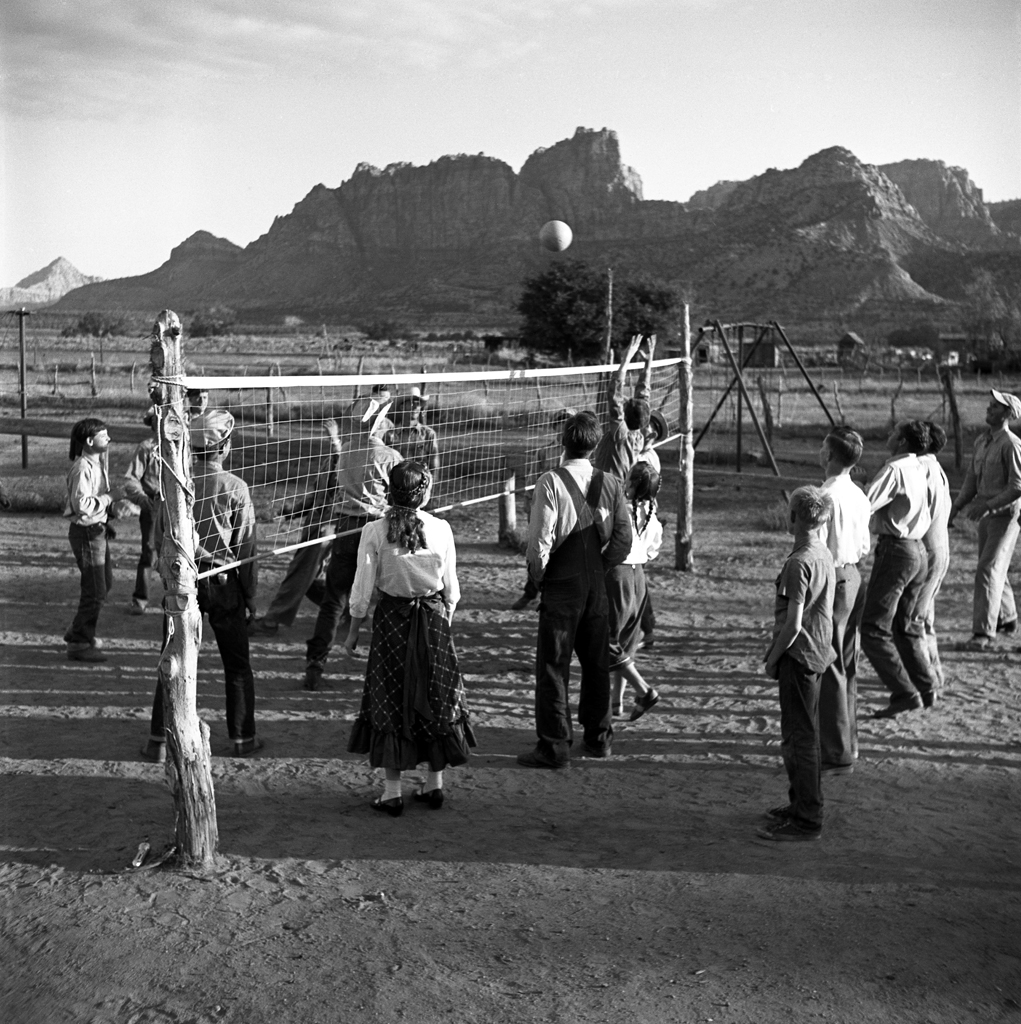

Just before dawn on July 26, 1953, Arizona law enforcement launched what has since become known as the Short Creek Raid: the arrest of men and women in an isolated community of Mormon fundamentalists who’d broken away from the church in order to live steadfastly — and illegally — in polygamy. According to a LIFE reporter invited to witness the event, “50 state troopers, five police matrons, 12 liquor inspectors, assorted photographers and the attorney general” descended on Short Creek (today known as Colorado City, Ariz.) and conducted the largest mass arrest of polygamists in American history.

The raid sent shock waves through other “plural marriage” communities — and, many people have argued in the years since, led directly to the sort of secretive, insular and insidious polygamist sects (like the one led by convicted child abuser and self-proclaimed Mormon “prophet,” Warren Jeffs) that have made headlines in recent years.

Here, six decades after Short Creek, LIFE.com offers a series of pictures — most of which never ran in LIFE — made by photographer Loomis Dean during a government raid on a small, isolated religious community.

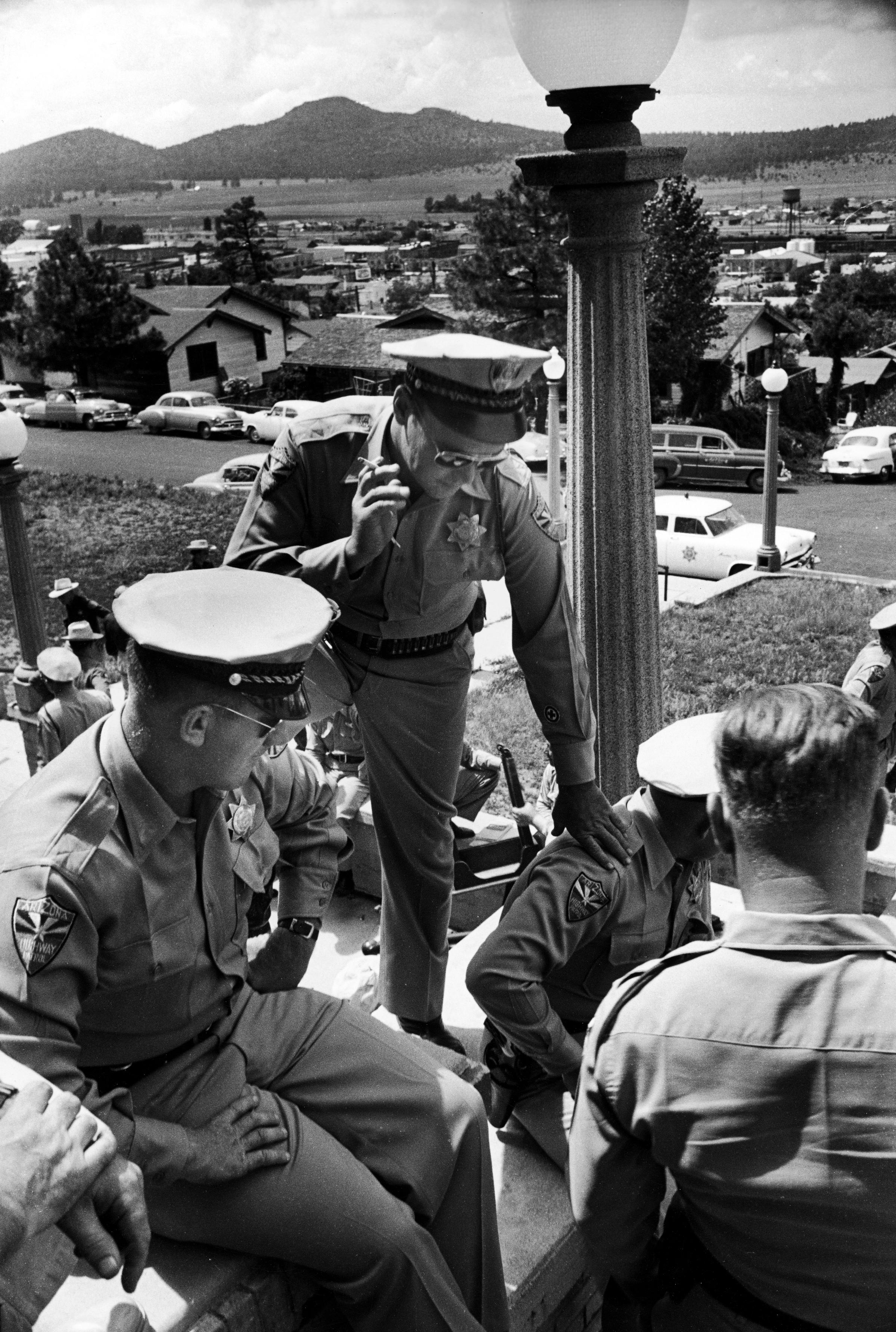

The day before the raid, the police — organized into teams — went over their plan. Accompanying photographer Dean was reporter Frank Pierson, who wrote in the notes that he sent back to LIFE’s editors in New York: “Leaving from points as far as 350 miles from Short Creek the groups were to converge on the town at exactly 4 AM Sunday. The Attorney General’s office prepared 122 indictments (36 men, 86 women) for insurrection. Officers were equipped with extra John and Jane Doe warrants to provide for the unexpected.”

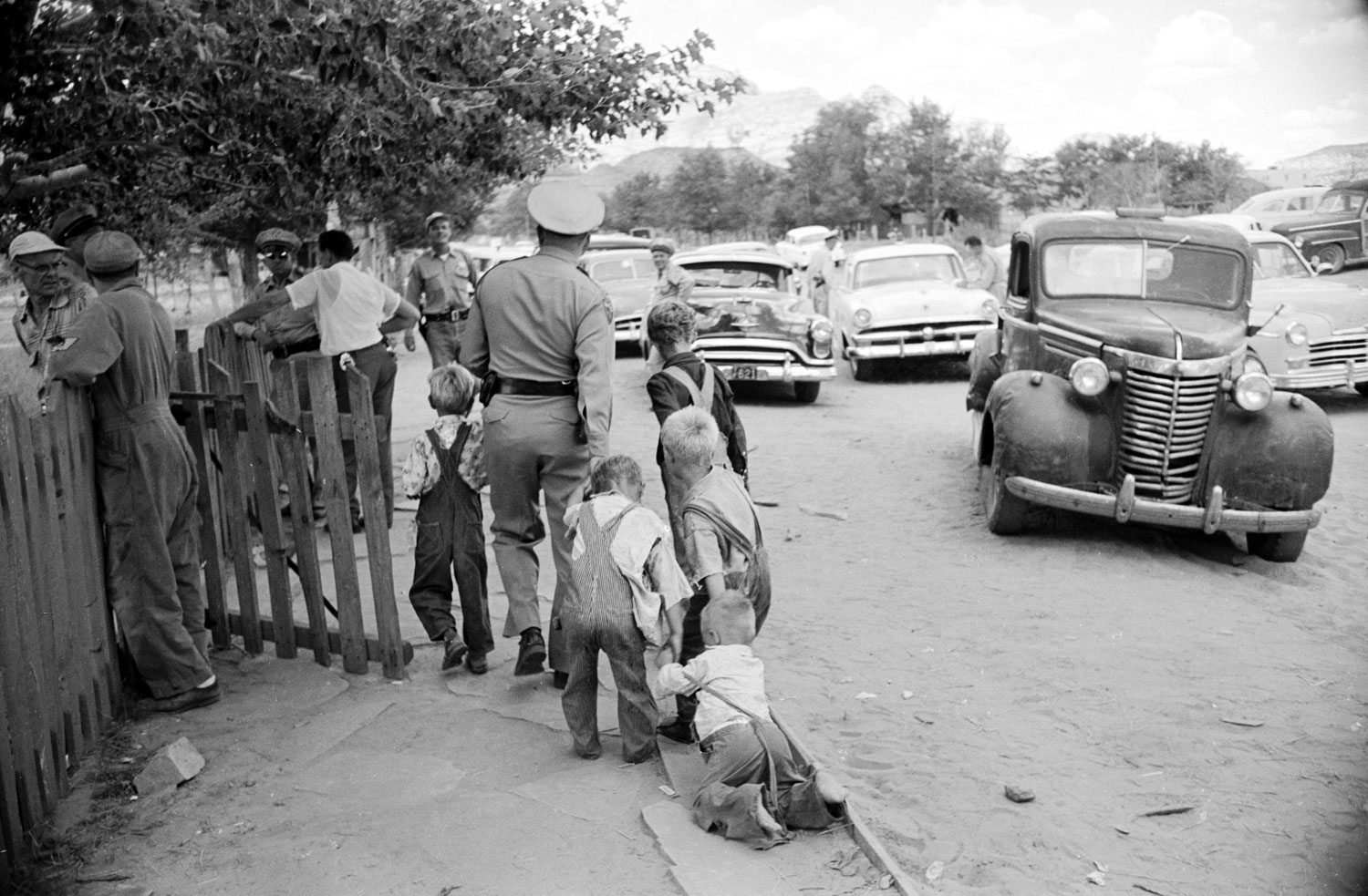

“For all the cloak and dagger work, there was a leak,” Pierson’s notes continued. “As patrol cars roared into the village three dynamite explosions echoed off the desert cliffs; they were signals to the waiting Short Creekers that the police were coming. In the houses, officers found only women and children cowering. The men were assembled in their Sunday best in the schoolyard. The American flag was flying, and they were singing ‘[God Bless] America.'”

In its article about the raid, published a few weeks later, LIFE observed, in a tone clearly skeptical of the need for the show of force brought to bear on a tiny community in the middle of nowhere: “It was like hunting rabbits with an elephant gun.”

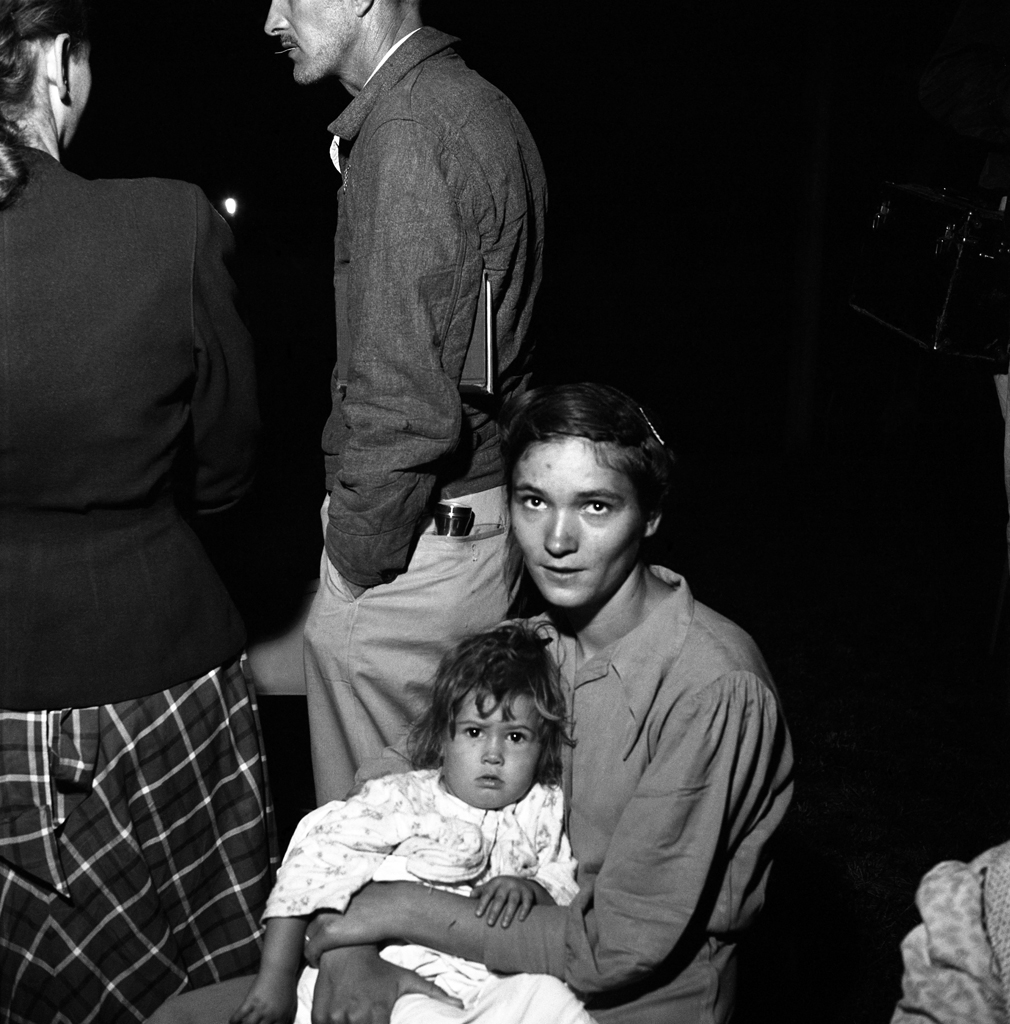

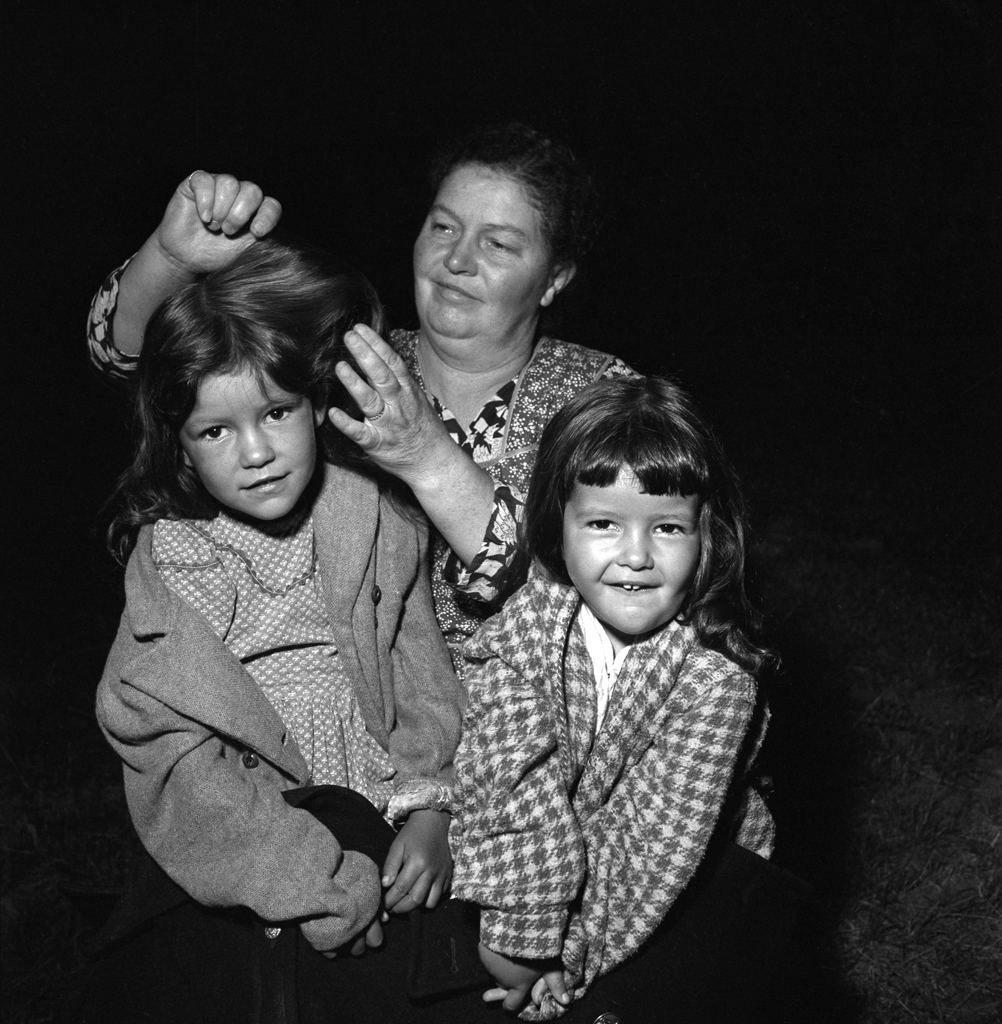

One hundred and twenty-two adults were served warrants. The men were arrested and sent to a jail in nearby Kingman; most of the women were forcibly sent away to Phoenix, and their children were placed in state custody, many given away to foster homes — some never to return to their families. Though officials consciously made the raid a media event, the resulting photos — particularly shots of crying children being taken from their parents — brought an outcry against the arrests.

The raid was also seen as a warning to polygamists elsewhere — including the Allred family of neighboring Utah, where a terrified little girl named Dorothy was already being taught to keep secrets about her father and seven mothers. Today, Dorothy Allred Solomon is an author who has written several books about growing up in polygamy; she spoke with LIFE.com about the Short Creek raid and its effect on her own life and on polygamist communities throughout the Southwest.

“I just have such a strong emotional response [to these photos]”, she told LIFE.com, choking up. “I was a little girl when these things happened, but I was conscious of them, and I was fully aware of the implications that families could be broken up.”

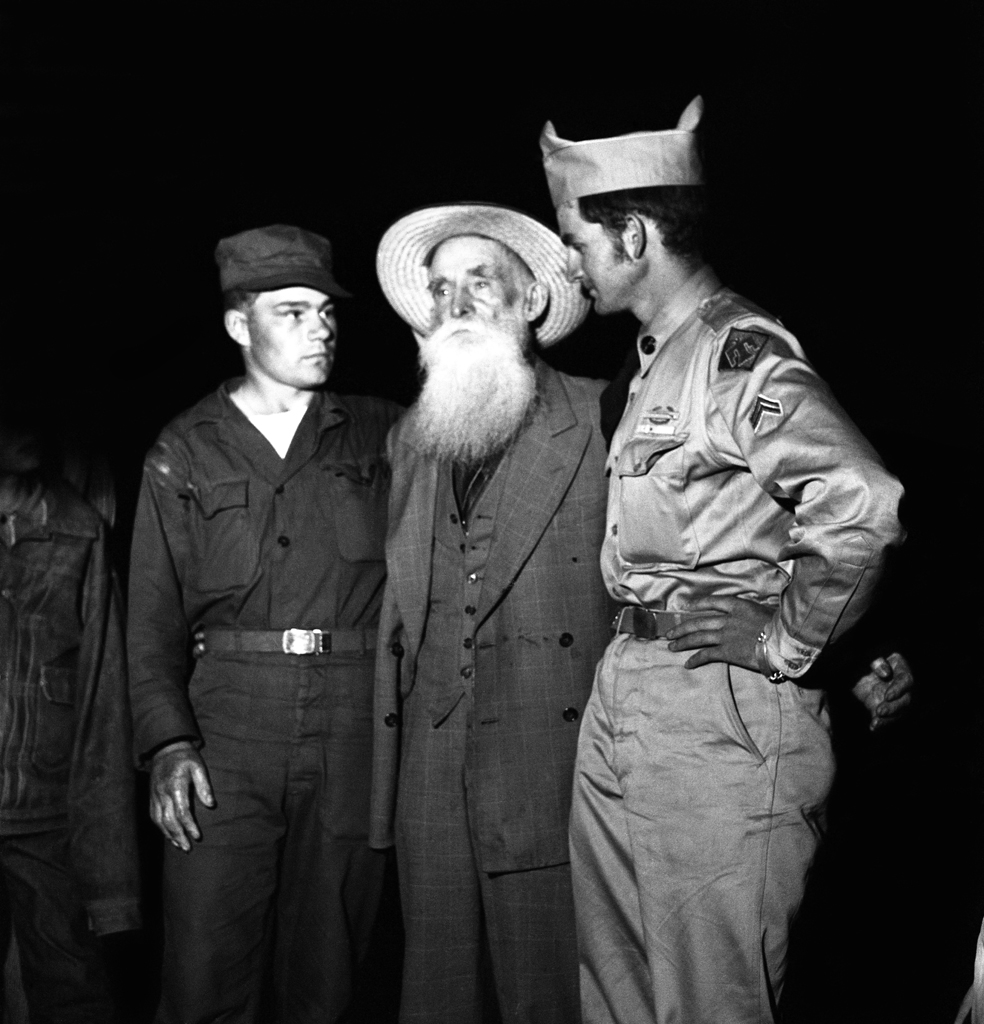

In many of these pictures, Solomon recognizes a familiar expression on the faces of the people (primarily the men) being arrested. “There’s an earnest look, and a desire to be cooperative, but at the same time, there’s total mistrust,” she said. “That was our posture — that was my father’s posture — toward the law.” Her dad, Rulon Clark Allred, spent eight months in jail in Utah after being convicted of bigamy. “He tried to be law-abiding in every other way — he was law-abiding in every other way. We were held to such a high standard of morality and integrity. And yet it came down to whether they would sacrifice a religious belief that they earnestly believed in.”

Then, as now, authorities had what appeared to be legitimate concerns about the treatment of women and children living in polygamist enclaves.

“This is a white-slave factory,” an assistant attorney general in the Short Creek Raid said in 1953. “No woman has escaped this community for at least ten years. They are forced to submit to men old enough to be their grandfathers.” The questionable way in which the raid was conducted, however, undermined a good deal of the legal and even the moral validity those claims may have had, and created an environment of fear and even deeper, bedrock distrust of government authority among fundamentalist Mormons.

“It set back efforts to control what was going on in those communities fifty years,” Ron Barton, who has led investigations into the polygamist community of Colorado City in recent years, told People magazine in 2003. For all the families it broke up and all the attention it received, the raid resulted only in probation for the men arrested.

Reporters, photographers, and television crews from NBC and CBS were invited to cover the raid. “An unappetizing affair at best, it was made no better by overtones of publicity grabbing,” reporter Frank Pierson noted.

After the raid, fearful polygamists “went way underground,” Dorothy Allred Solomon says. “And when people go underground like that, it creates shadows and darkness for people like Warren Jeffs to exploit other people’s paranoia. The reason someone like Jeffs could come to power was because of this raid in 1953 — he totally used people’s fears.” Jeffs rose to power in that very same town (later renamed Colorado City) decades after the Short Creek raid; there he ruled as president of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Once on the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted list, he is currently serving a life sentence in a Texas prison, having been convicted of two counts of child sexual assault.

The 1953 raid, Solomon notes today, spooked her own family enough to leave their compound in Utah, rather than risk her father going to jail again and the children being taken away.

“That was the catalyst for us scattering to the four winds,” Solomon recalls. “It changed our lives forever. And I never really got my family back again in the way I’d had it for the first few years of my life.”

In a follow-up story on the raid in September 1953, LIFE reported that 84-year-old community patriarch Joseph Smith Jessop (see slide 7 in gallery) and other male residents returned to Short Creek following their arrests to await trial, but found it desolate, with a great number of the women and children gone. “The shock of the arrest was too much for the staunch old Mormon,” the magazine wrote in the article, ‘The Lonely Men of Short Creek.’ “A month after the raid, heartbroken, he died.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com