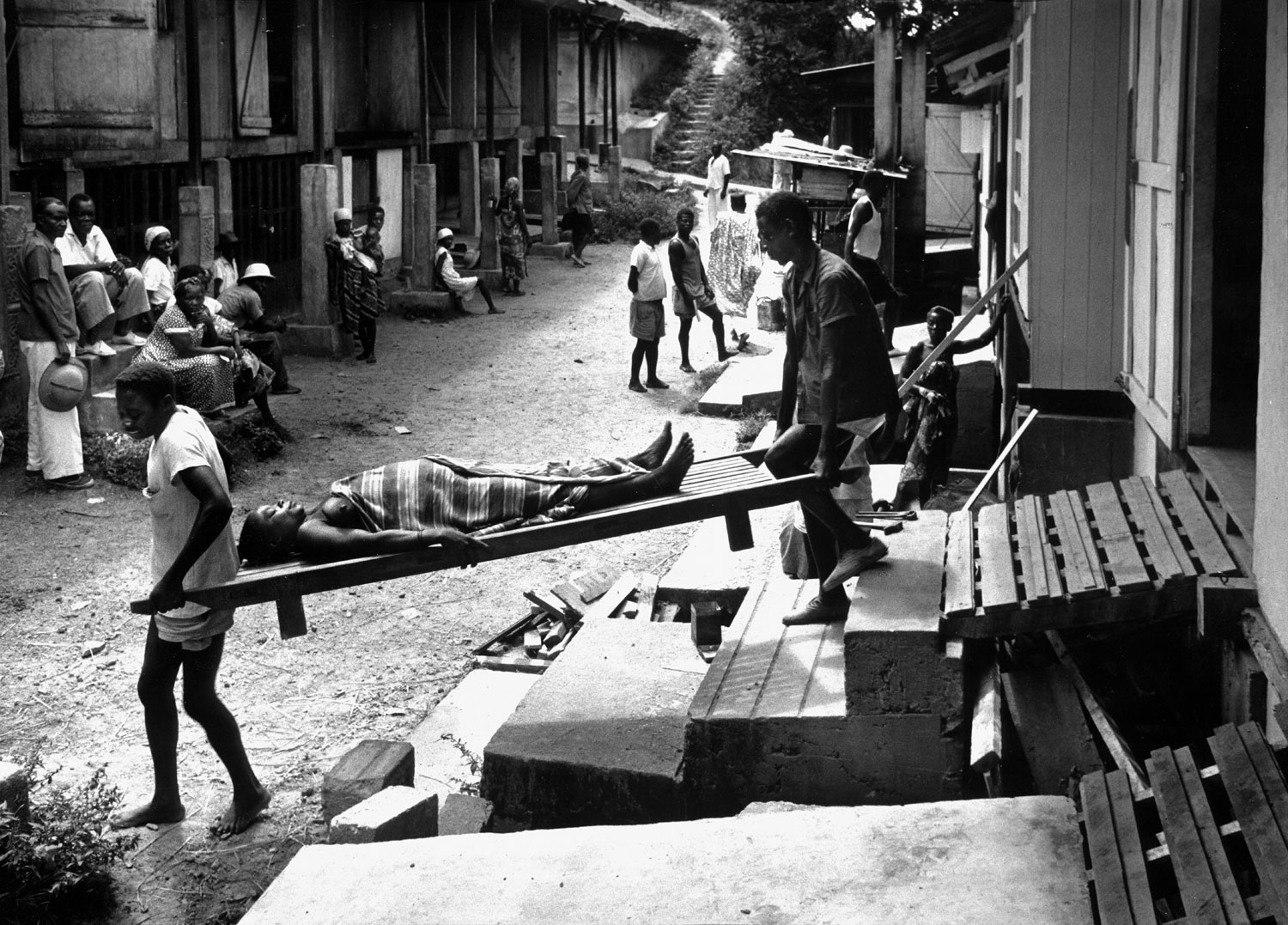

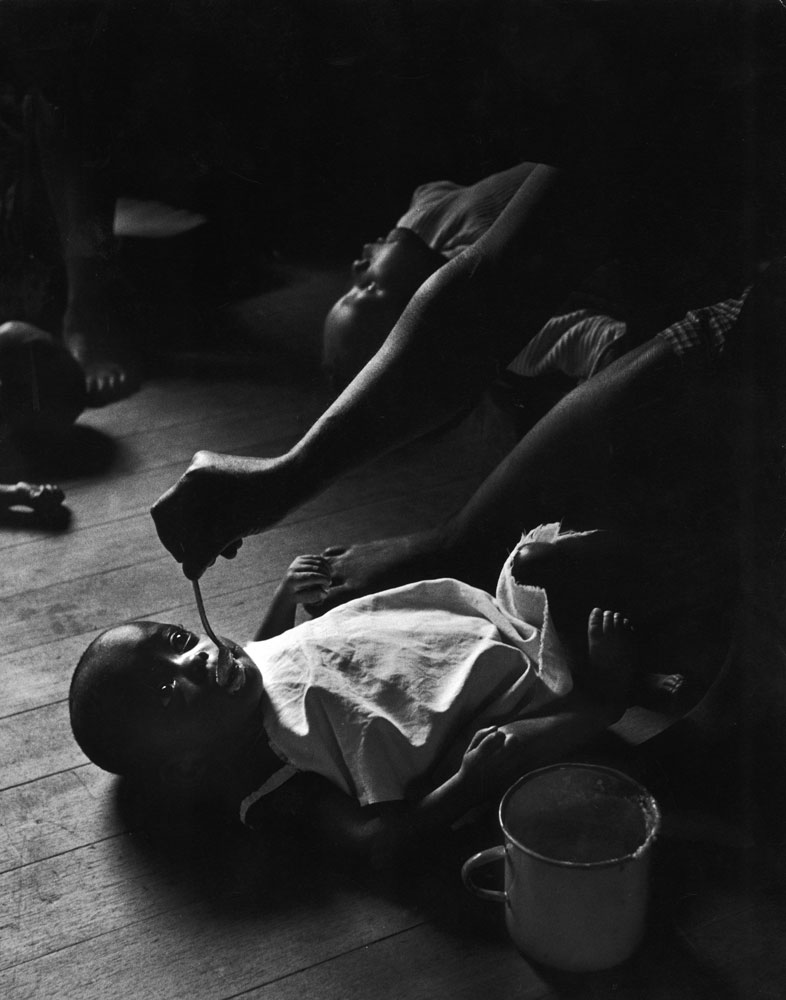

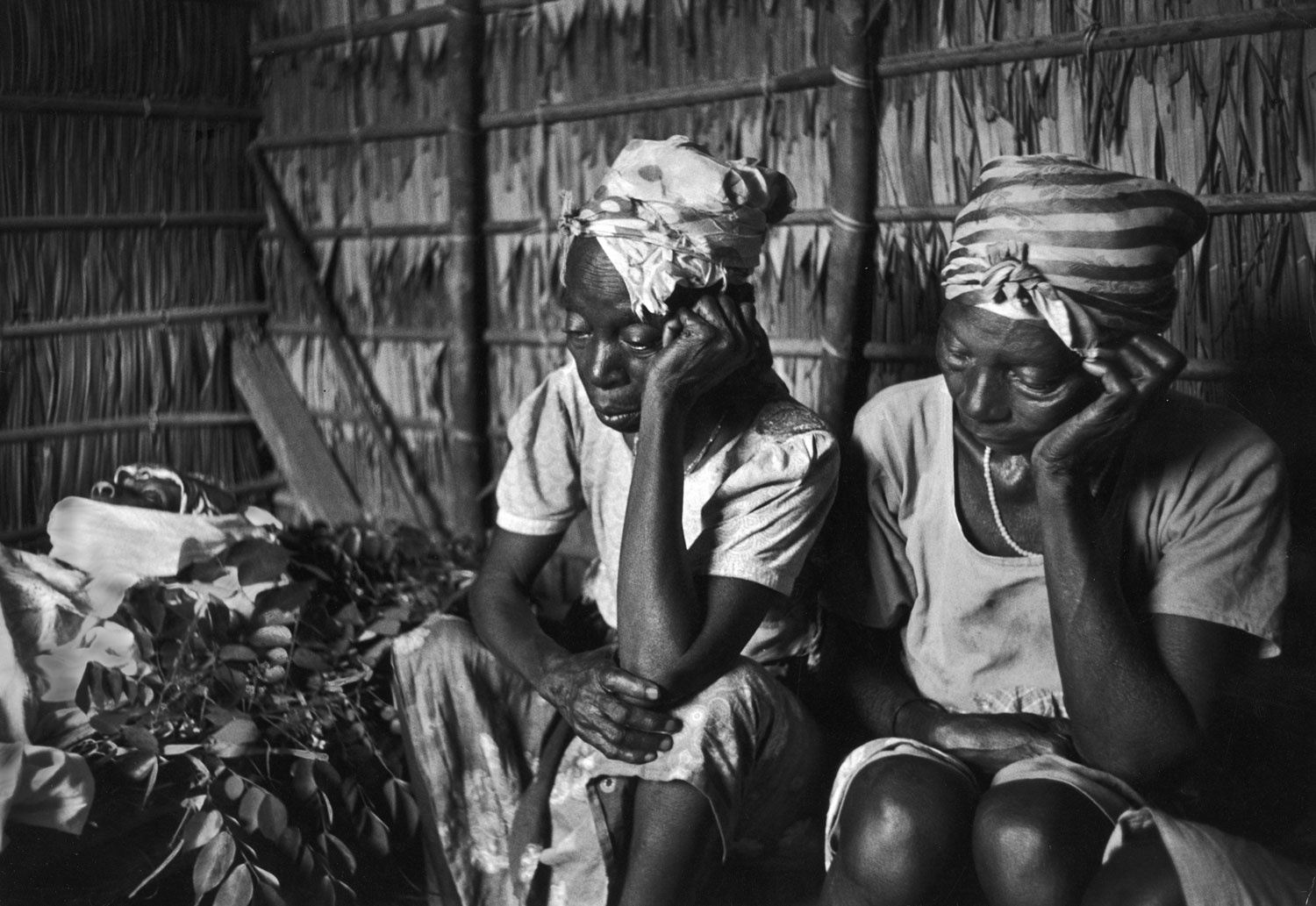

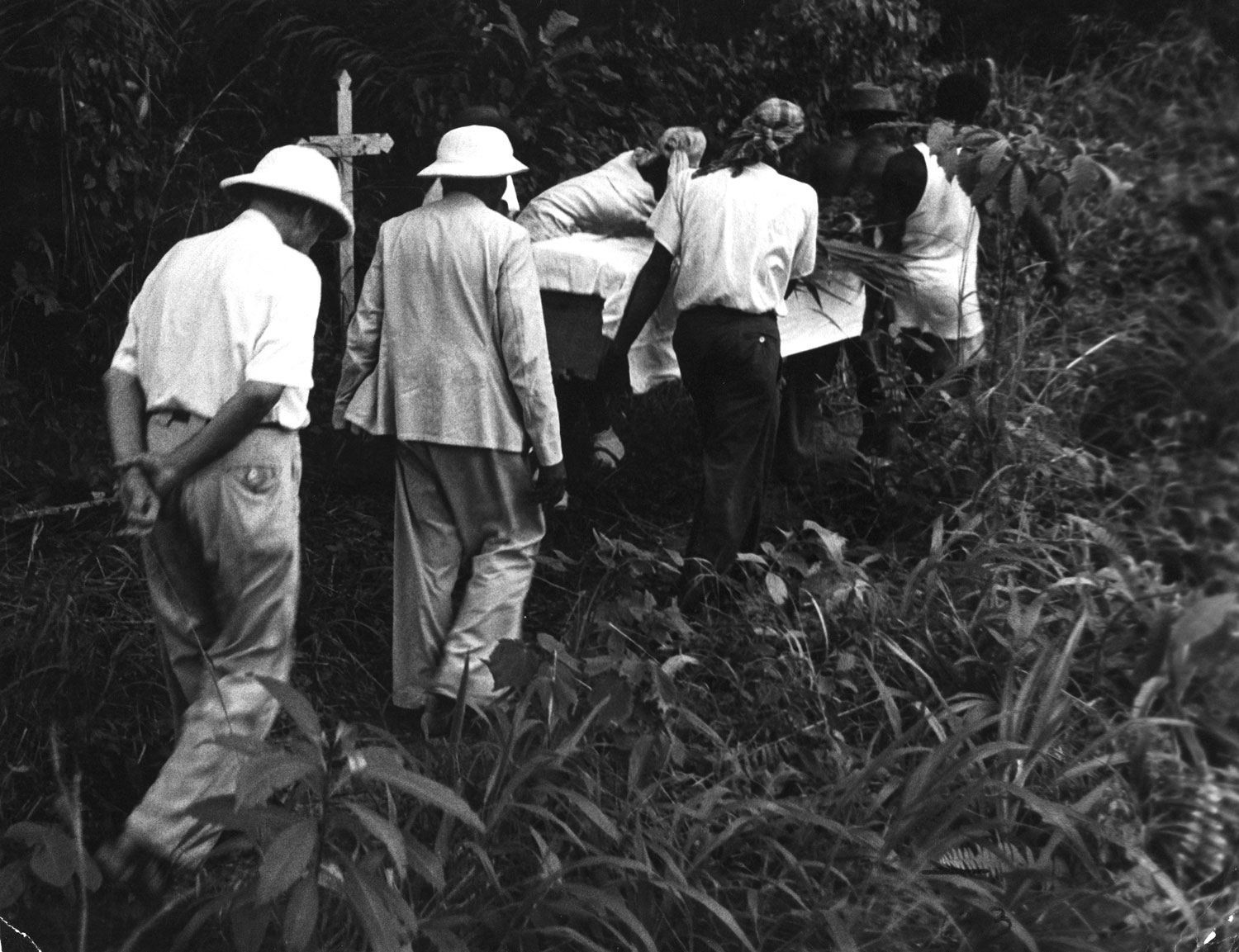

Albert Schweitzer — the Nobel Peace Prize laureate, theologian, musician and “medical missionary” who spent decades in West Africa — was one of the most recognized figures of the 20th century. To some, he was a well-meaning but ultimately patronizing European bent on enlightening the “Dark Continent” of Africa; to others he was a man whose tireless work with men, women and children suffering from leprosy, malaria, elephantiasis, whooping cough, venereal diseases and countless other vile illnesses elevated him to something close to sainthood.

The reality of Schweitzer’s life and work, meanwhile — as it almost always is in these sorts of cases — was both more complicated and more deeply fascinating than either of those rather simplistic estimations of the man.

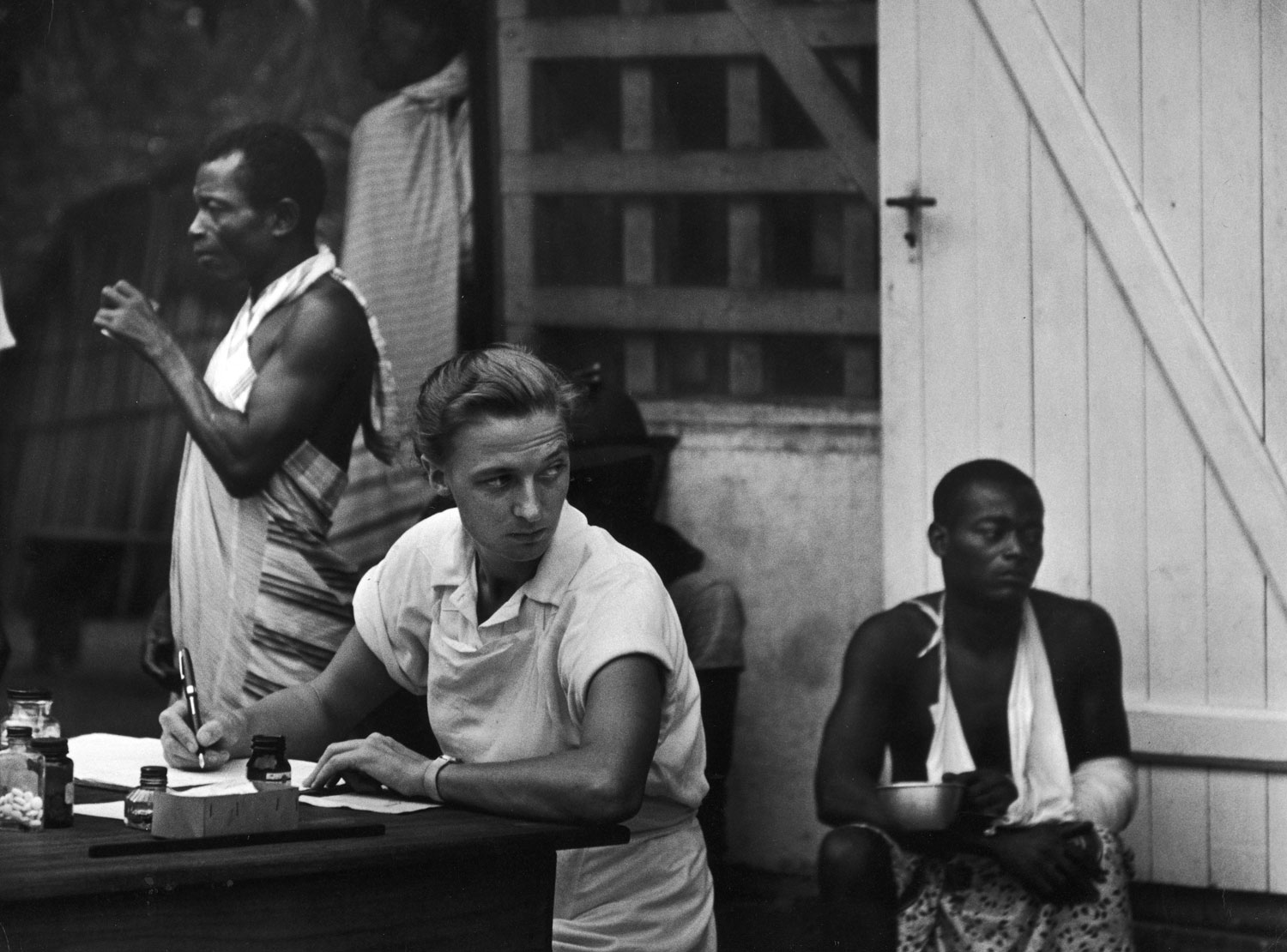

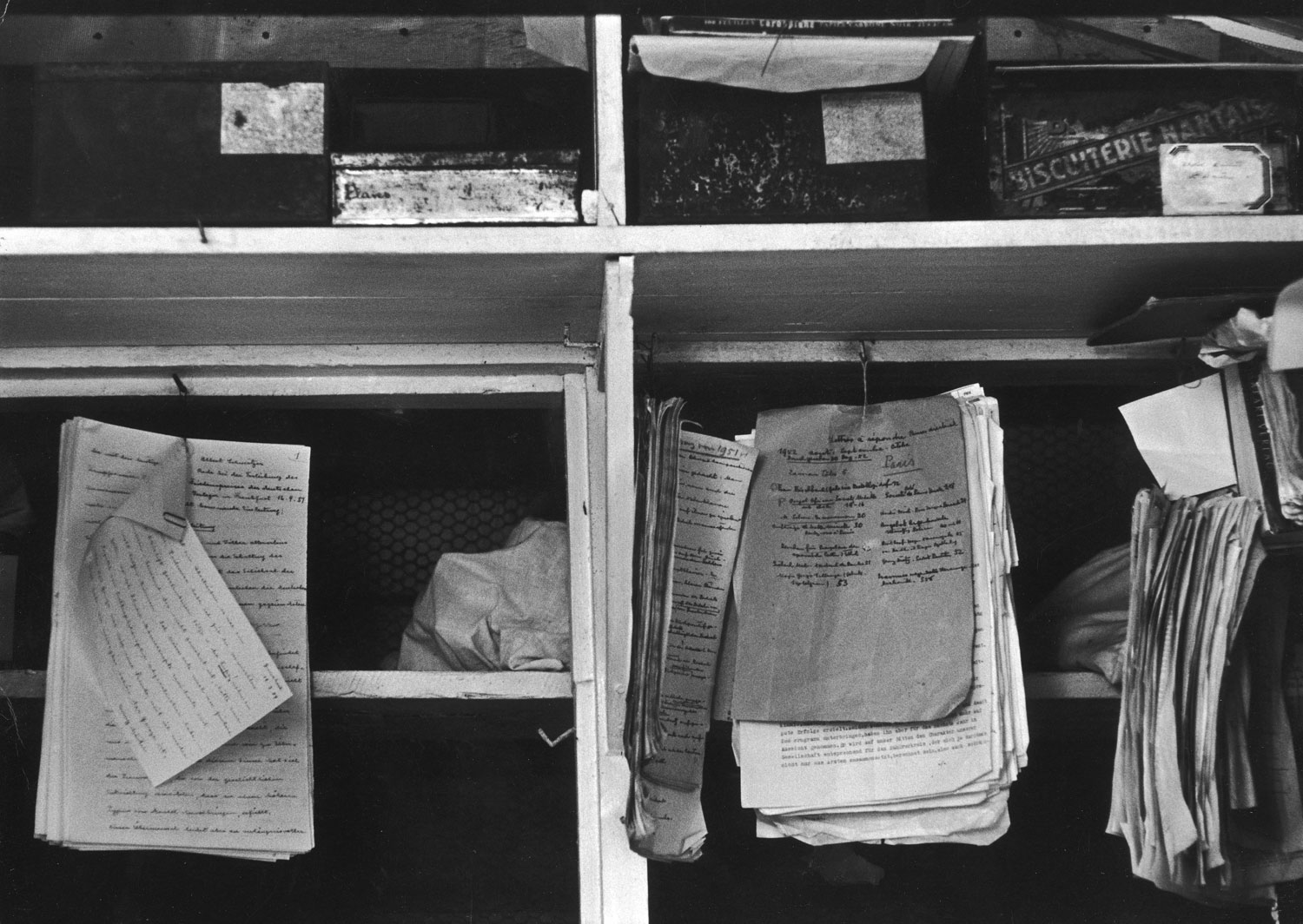

In November 1954, LIFE magazine published a feature story on Schweitzer, “A Man of Mercy,” with photographs made by the great W. Eugene Smith. Here, LIFE.com republishes Smith’s photos of Schweitzer, as a reminder of the man’s stature — and a celebration of one photographer’s singular vision.

In that issue, LIFE wrote:

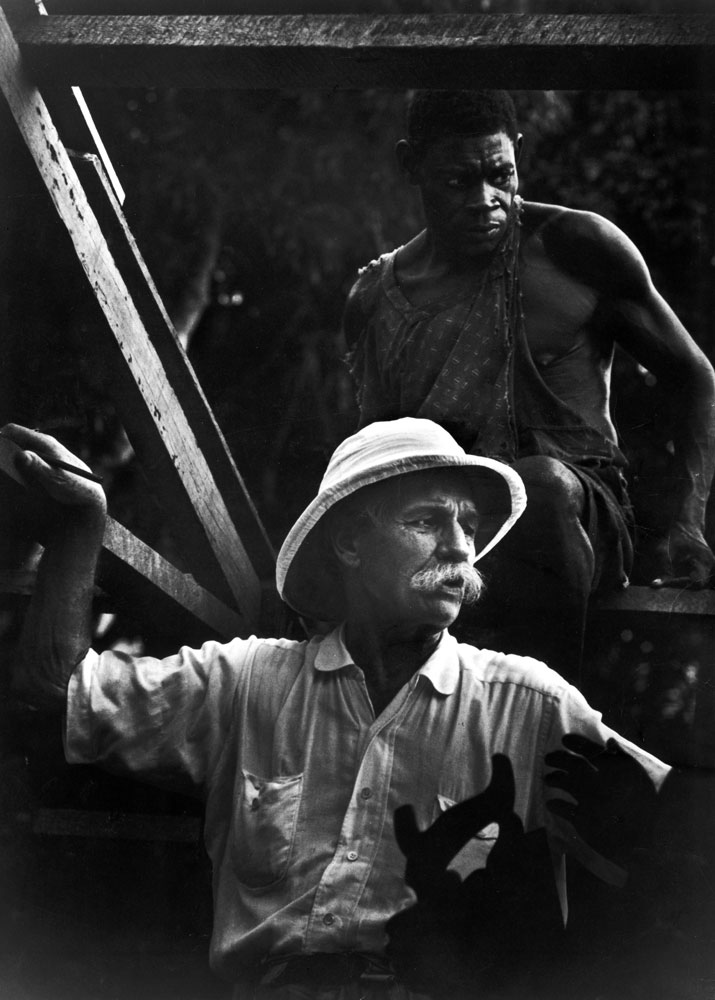

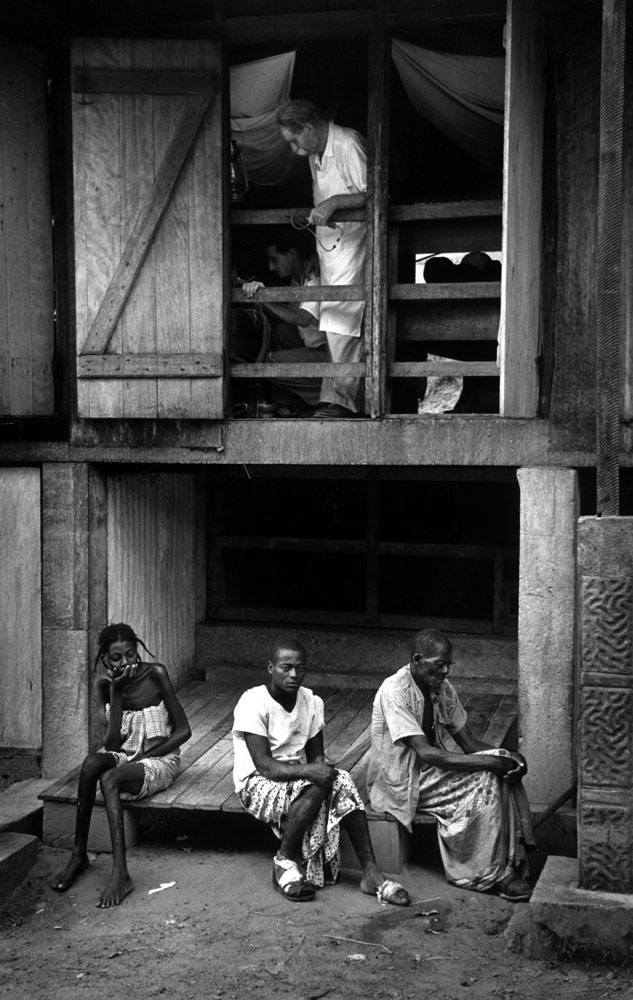

“No one knows me,” Albert Schweitzer has sad, “who has not known me in Africa.” In Norway last week, where he had come to acknowledge a Nobel Peace Prize, crowds jammed streets to cheer a great figure of our time. As they cheered they were convinced they knew him well: he is the humanitarian, warm and saintlike. In full manhood he had turned away from brilliant success as a preacher, writer and musician to bury himself as a missionary doctor on Africa.

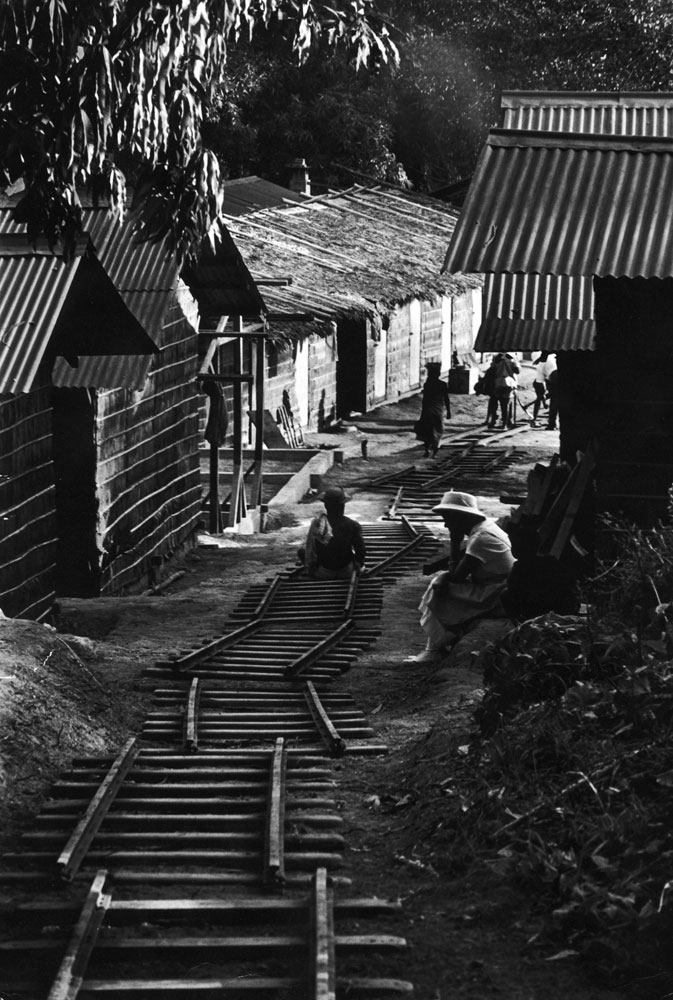

All this was truth — but admirers who have followed Dr. Schweizter to French Equatorial Africa [specifically, Gabon — Ed.] know a different man. There, amid primitive conditions, Europe’s saint is forced to become a remote, driving man who rules his hospital with patriarchal authority. For those seeking the gentle philosopher of the legend, he has a brief answer: “We are too busy fighting pain.” Then he turns back to the suffering and the work that make up the African world of Albert Schweitzer.”

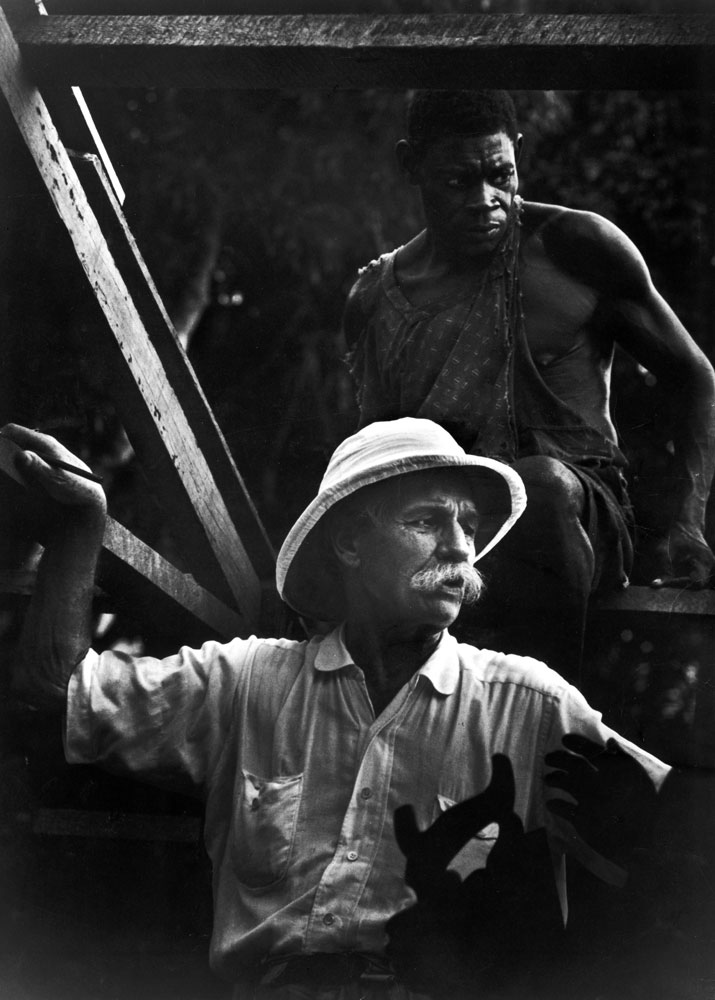

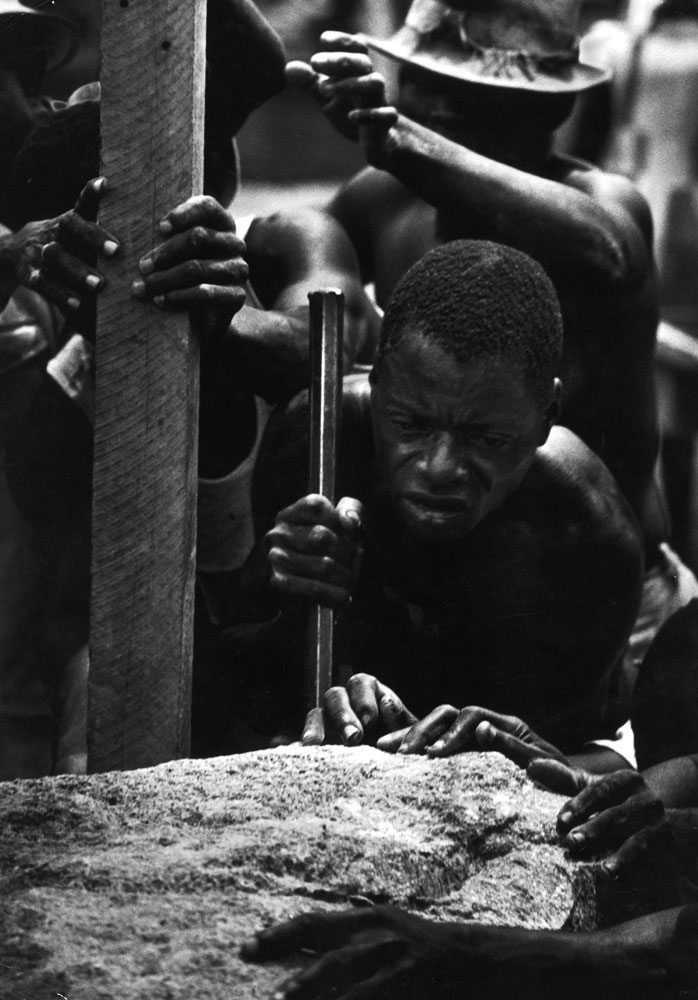

The story behind the most enduring image of the entire photo essay in LIFE, meanwhile, illustrates something quite elemental not about Schweitzer, but (characteristically) about the prickly, occasionally bombastic master photographer who made the picture, W. Eugene Smith. The photograph — the first in this gallery — is beautiful, and telling: here is Dr. Schweitzer, deep inside Africa, overseeing the building of a hospital. It is a portrait that captures so many aspects of the man in one frame: his dedication, the power of his personality, his magnanimity, his “otherness” and at the very same time the rightness of his presence in a land thousands of miles from his birth.

There’s really only one problem with this portrait: it’s not true. Or rather, what truth it contains only survives to this day because Smith drastically manipulated the photograph, combining elements from two separate negatives in order to impart in one picture the narrative he was dead-set on conveying. The silhouetted saw handle and human hand in the lower right of the frame were not part of the larger picture when Smith made it; instead, he combined elements of two distinct images to create a third, now-classic shot of a man quite literally on a mission. (One story says the saw and the hand were added to cover a blurred patch on the larger picture; others who know Smith’s work argue that he simply wished to add a new graphic element — and another layer of quiet drama — to the whole.)

That this sort of manipulation contravened LIFE’s own photojournalistic guidelines mattered little then — Smith, after all, developed and printed his own work, refusing to allow others to handle his film, his negatives, anything at all — and, in all honesty, it matters even less now. The fact of the matter is, by the time LIFE sent him to Africa to chronicle Schweitzer’s work and his world, Smith was already a legend. He had made some of the most memorable photographs to emerge from World War II (and been wounded while in the Pacific). He had pioneered the photo essay form for LIFE with landmark work like “Country Doctor” (1948) and “Nurse Midwife” (1951). He was prickly, difficult, indefatigable and routinely produced work that most photographers would give their right eye to have made.

The sort of tinkering Smith engaged in with that one, iconic Schweitzer photograph might be frowned upon today. Any contemporary photojournalist who admitted to such behavior would probably be excoriated by his or her peers, as well as by the general public.

W. Eugene Smith, on the other hand, has largely escaped such censure for one reason, and one reason only: he was W. Eugene Smith, and for better or worse, when it comes to aesthetics — and even, to some extent, when it comes to ethics — genius has always played by, and been judged by, a different set of rules than those that govern the rest of us.

— Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE.com

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com