By DAVID PESCOVITZ

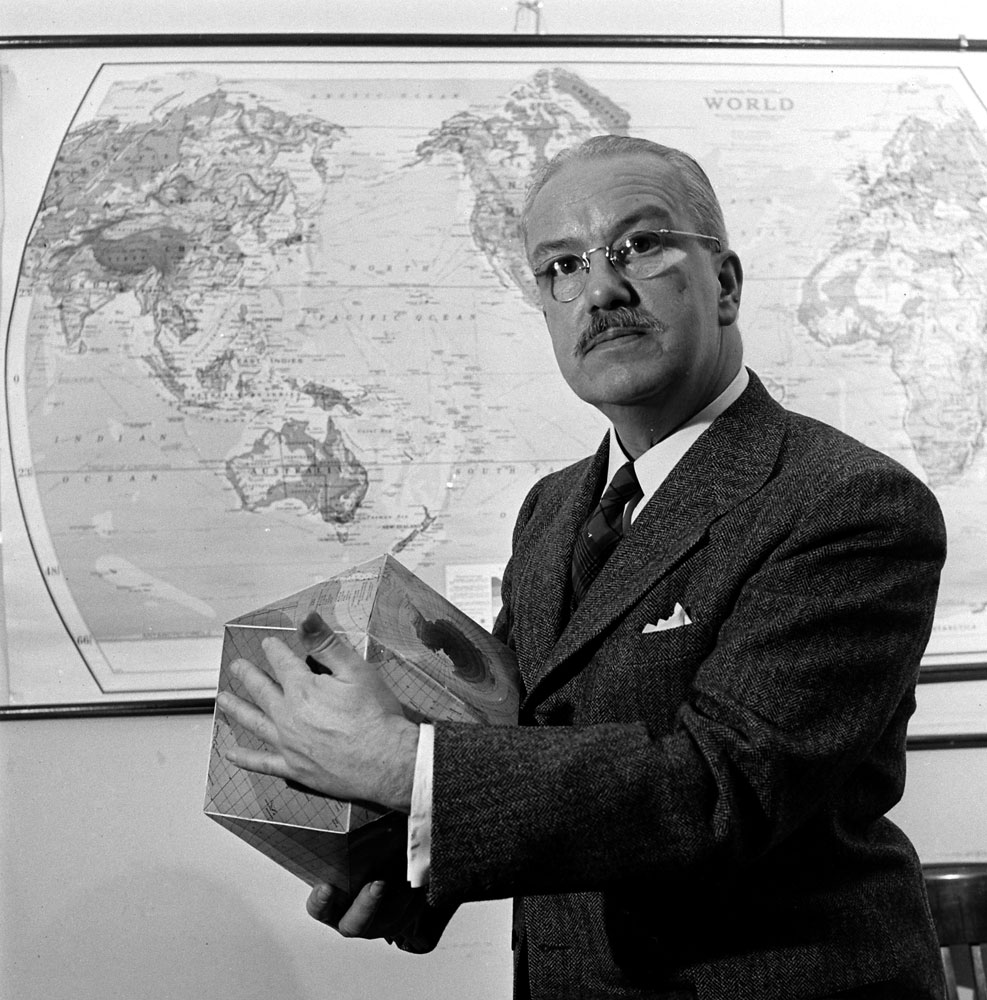

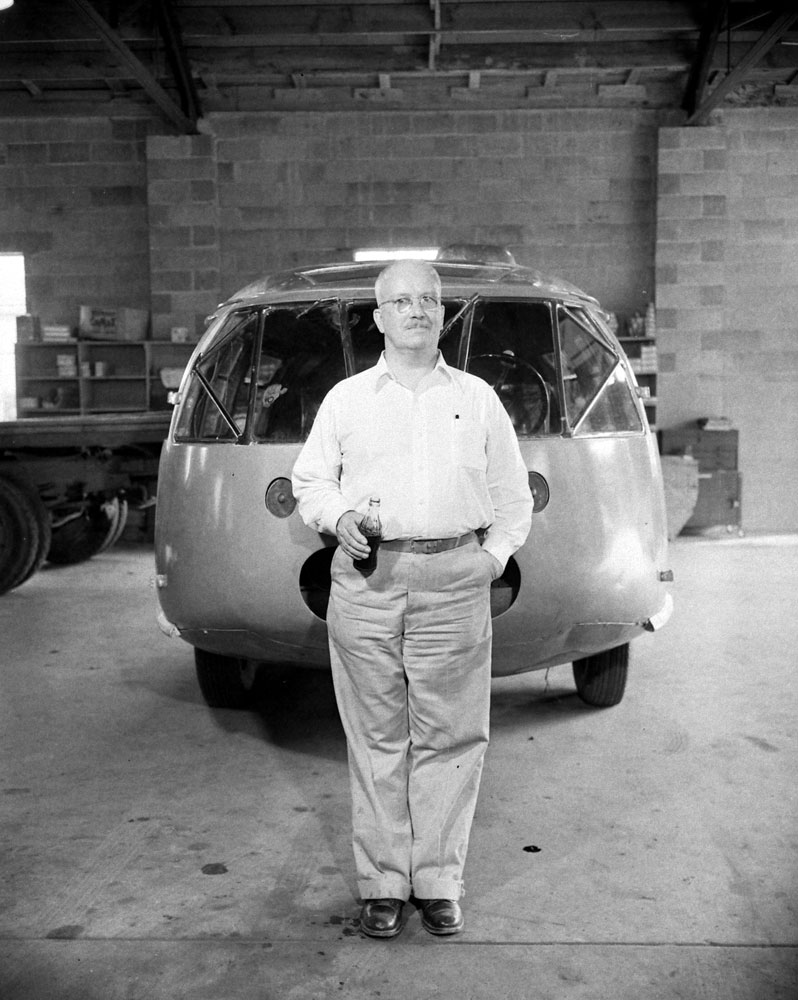

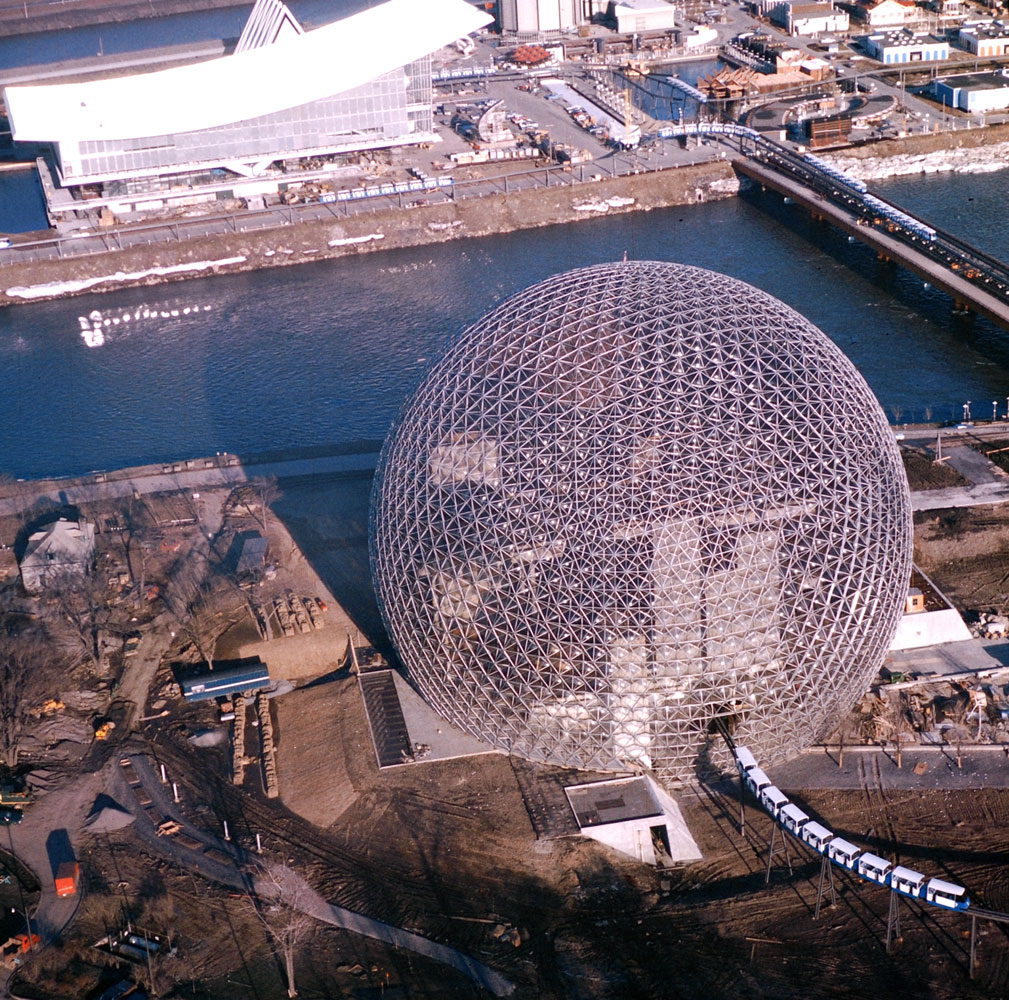

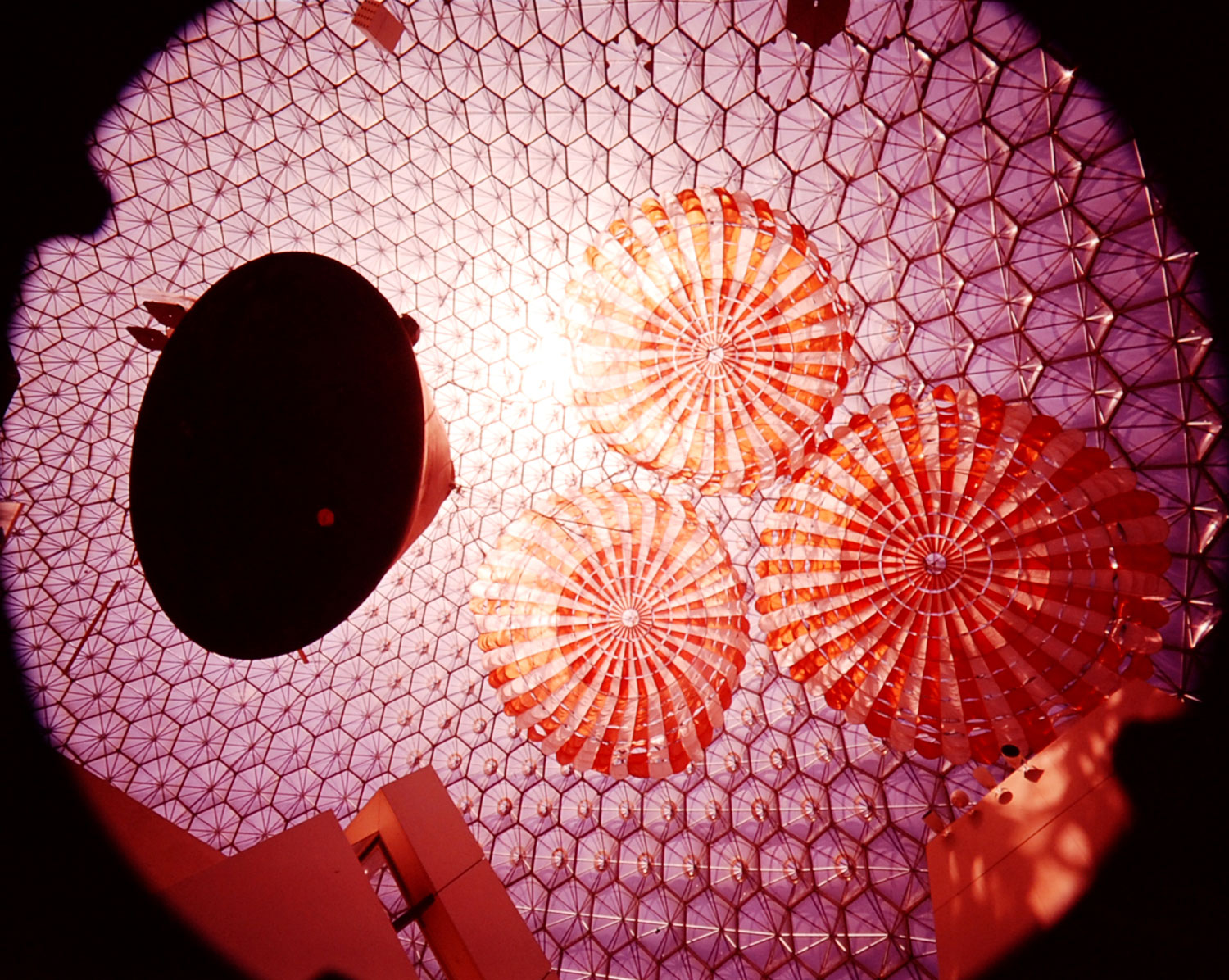

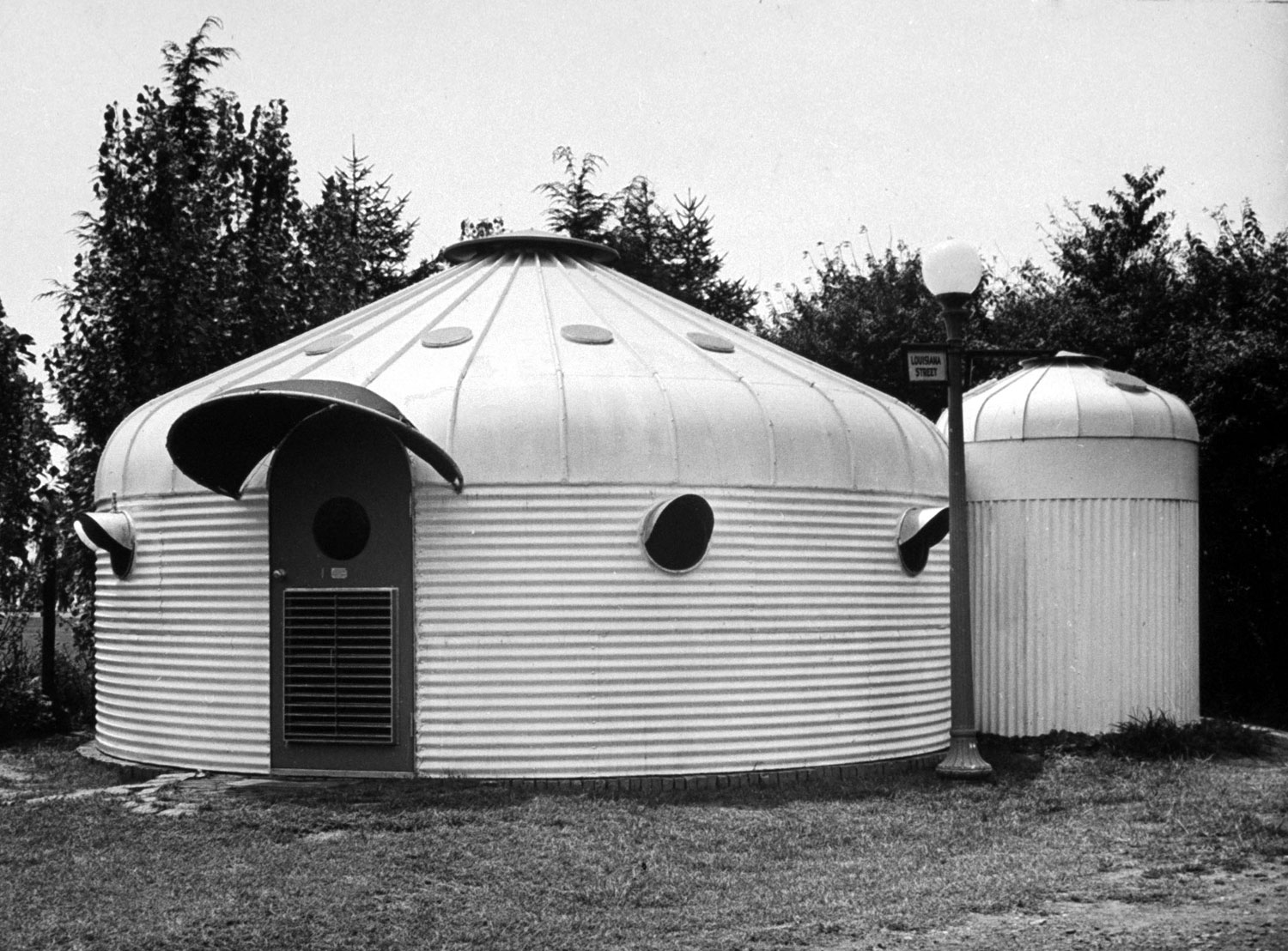

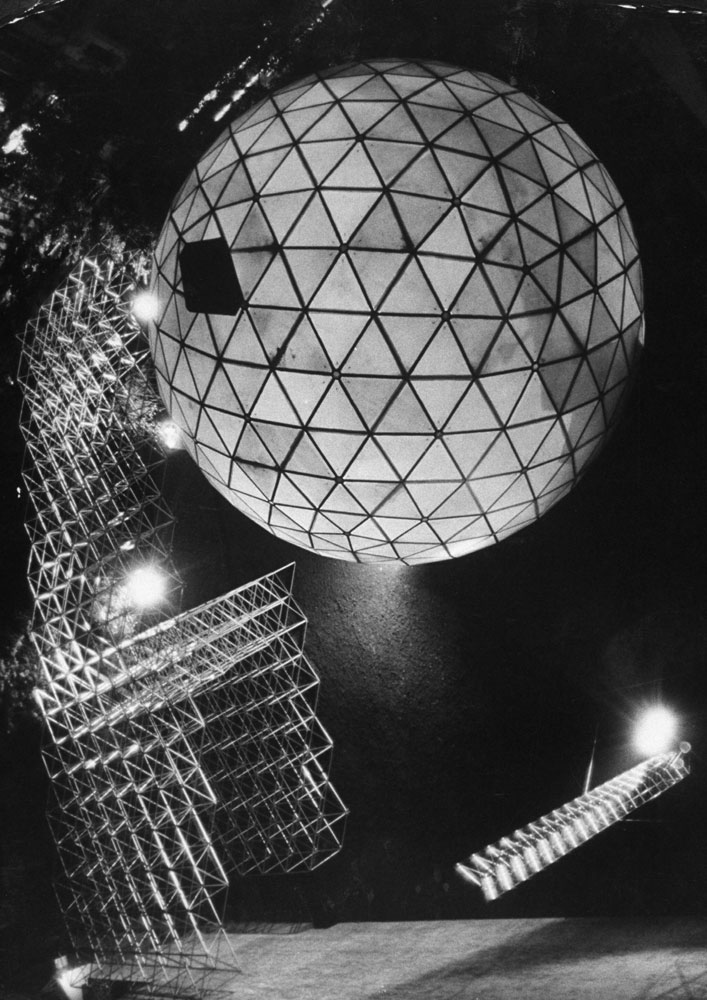

I don’t live in a geodesic dome. There’s no Dymaxion car in my garage (unfortunately, on both counts). And no Dymaxion map is likely to strengthen my embarrassingly poor grasp of geography. From a purely commercial perspective, the man behind all of those creations, Buckminster Fuller, was a failed inventor. And yet, at the same time, he was one of the most influential, protean innovators of the 20th century.

See, the curious inventions that Bucky is best known for were often mere incidental offshoots of his real genius. They were artifacts that embodied not a specific solution to a particular problem, but rather an entirely new way of thinking about the problem at its most fundamental levels. “I did not set out to design a geodesic dome,” he once said. “I set out to discover the principles operative in Universe. For all I knew, this could have led to a pair of flying slippers.”

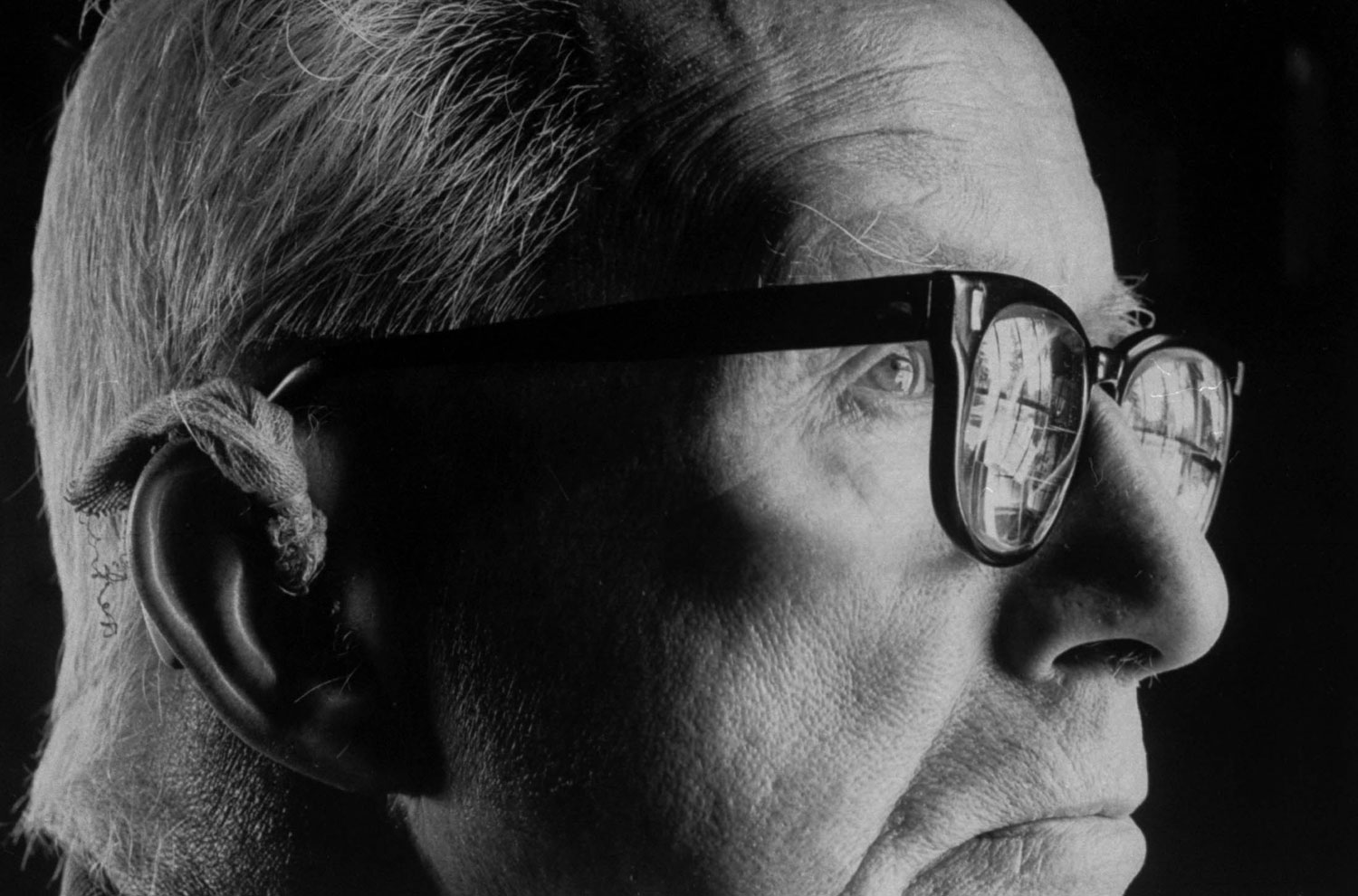

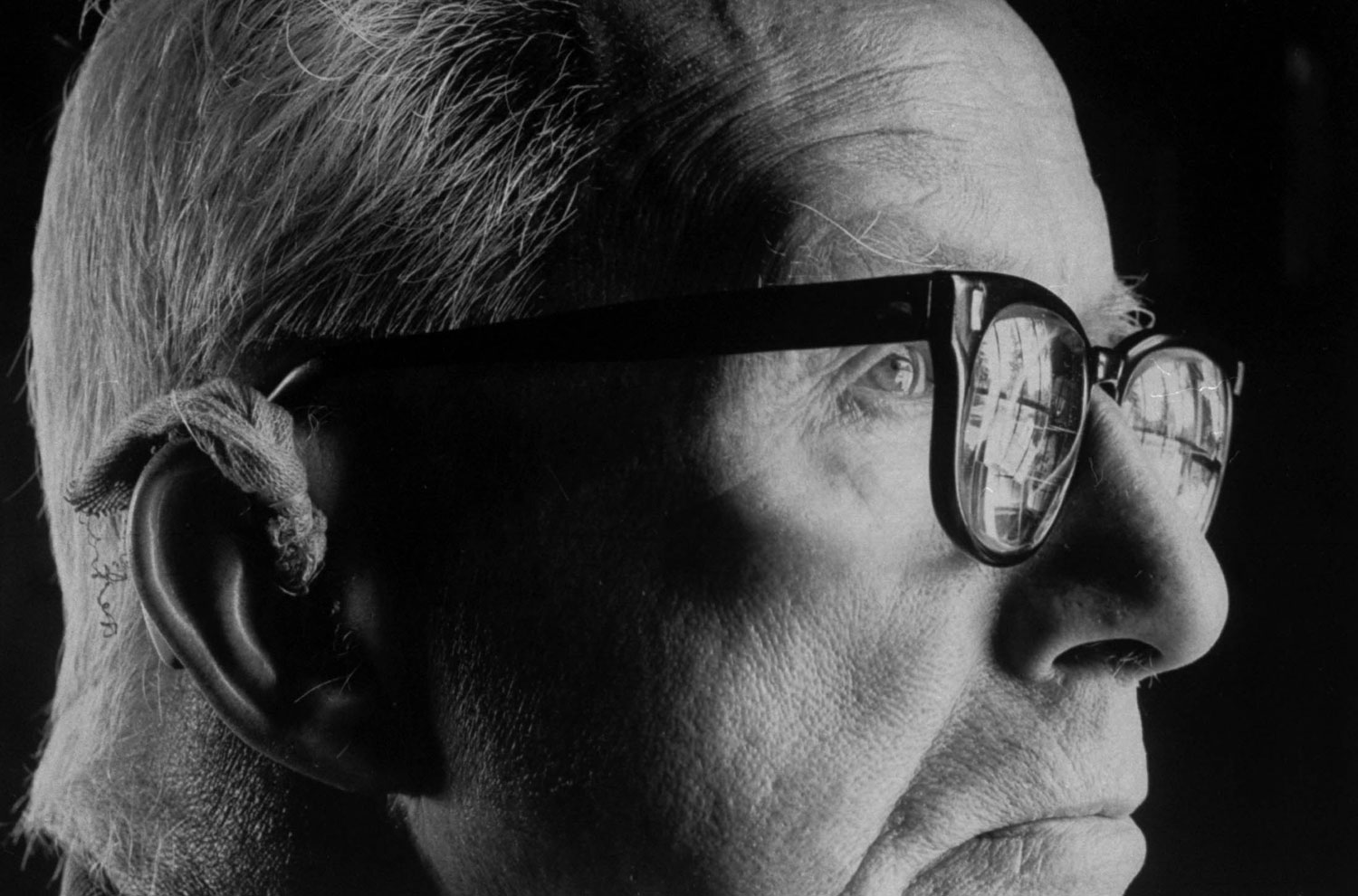

Bucky Fuller reads mail during a boat ride near his summer home in Maine, 1970. (John Loengard—Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

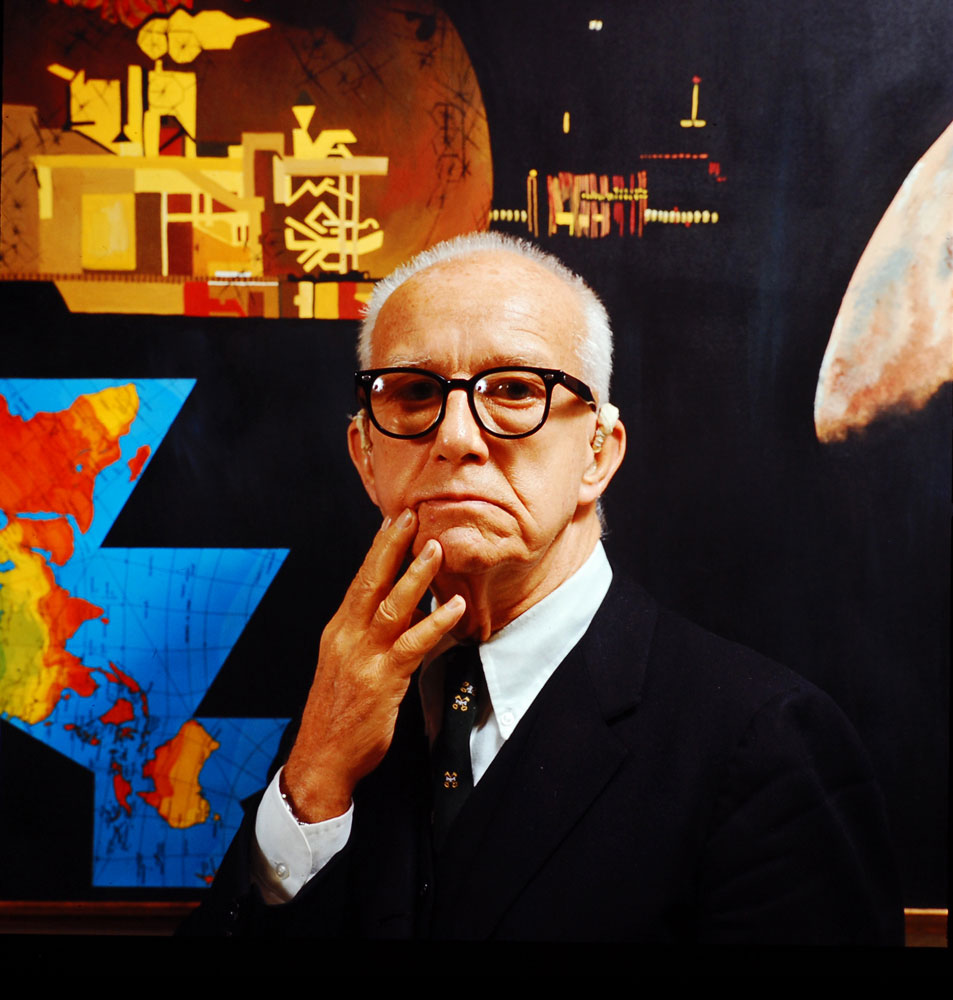

Bucky Fuller (b. July 12, 1895, in Massachusetts; d. July 1, 1983, in Los Angeles) was a practical philosopher who made his ideas tangible. His mediagenic inventions were vectors that spread his big ideas through popular consciousness, spurring conversations about poverty, transportation, ecology, housing, energy and other transformational topics of the day (and of future days). At the Institute for the Future, where I’m a researcher, we call this methodology “human-futures interaction.” And it works. A good “artifact from the future” will provoke the person who sees it, and touches it, to think about the future and hopefully make better decisions in the present. It’s not easy, but Bucky was a deep thinker who learned to become a great maker. He was driven by curiosity and optimism that was infectious. His dozens of books laid out plans to fix, manage or design around the world’s problems. Whether you agreed with his solutions didn’t matter much. In fact, it still doesn’t.

The real lesson in his books is in the beauty (and joy) of whole-systems thinking. Playing connect-the-dots — with science, technology, art, music, people — is one of my favorite pastimes. Re-encountering Bucky, I’m constantly reminded of how much I don’t know, the importance of unintended consequences and that the most interesting experiences, insights and breakthroughs are often found at the intersection of disciplines and, sometimes, at the very fringes of reason.

David Pescovitz is co-editor/partner at Boing Boing and a research director at Institute for the Future. He is also editor-at-large of MAKE. (Photo: Bart Nagel)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com