Ask any ten people on the street to name an architect—any architect, living or dead—and chances are pretty good that most would reply, “Frank Lloyd Wright.”

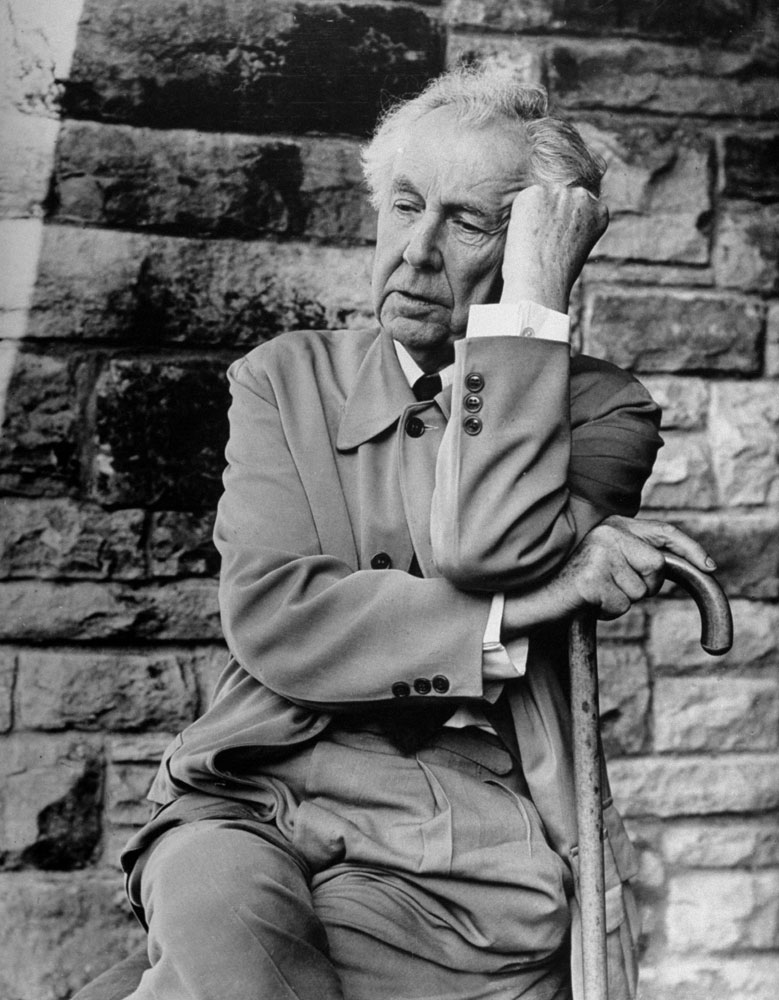

It’s hardly surprising, of course, that six decades after his death, Wright (1867 – 1959) remains America’s, and perhaps the world’s, most recognizable architect. Aside from the unassailable brilliance of his creations (the breathtaking Fallingwater and the Guggenheim Museum alone would have assured his legend) and the almost unimaginably scandalous life he led (open infidelity; the abandonment of his wife and his six children; outrageous cost overruns on projects; public conflicts with his patrons),Wright himself was, physically and stylistically, a memorable man. With his white mane of hair and his consciously striking sartorial sense, he hardly sought to avoid attention.

Wright was a genius, and like most geniuses, he wanted the world to notice him and his works. Here, on the anniversary of his landmark Guggenheim Museum in New York opening to the public for the very first time (Oct. 21, 1959), LIFE.com does just that—we pay attention to the man and celebrate some of his signature creations.

For its part, LIFE magazine paid tribute to Wright and to his eye-popping 5th Avenue museum this way, in its Nov. 2, 1959, issue:

Last week, six months after he died, the spirit of Frank Lloyd Wright came triumphantly to life again in New York City. The revolutionary art museum he designed for Solomon R. Guggenheim was finally opened to the public. While it was under construction, the museum was the constant butt of jokes. Its cylindrical exterior was likened to everything from a washing machine to a marshmallow.

The inside of the new Guggenheim Museum proved to be far more sensational than the outside. To the visitors who streamed through, it seemed like the inside of a giant snail shell. . . . The museum was greeted with a barrage of praise and protest. Architects hailed the “fantastic structure,” museum directors complained of the slanting floors and walls. An art critic called it “America’s most beautiful building,” a newspaper labeled it a “joyous monstrosity.” Everyone agreed on one thing—the building was definitely dizzying. This physical reaction would have pleased Wright who predicted, “When it is finished and you go into it, you will feel the building. You will feel it as a curving wave that never breaks.”

A curving wave that never breaks. Coming from a man who was inspired by the myriad forms and shapes found in nature for much of his protean career, that simple statement is perfectly apt—and still, all these years later, somehow comfortingly true.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter @lizabethronk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com