The French surrealist Jean Cocteau’s 1930 film, Blood of a Poet ― in which a young artist finds himself in a world where, among other oddities, gravity is reversed and guns shoot backwards ― is an at-once patently absurd and entertaining work of art.

Shot by Cocteau with financial help from the notable French patron, Charles, Vicomte de Noailles, the movie is a visual smorgasbord of thematic references and stylistic quirks. Narcissus of Greek legend appears in its mirrors; hints of Victorian Mesmerism are glimpsed in its whirling wheels; and, in its boy-like angels, Jungian archetypes play their roles. Packed with narrative non sequiturs, Blood of a Poet is a slow, if often-giddy, ride. Crucially, it also got the 40-year-old Cocteau noticed.

Cocteau, who died 50 years ago this week (Oct. 11, 1963), released the movie at a time when Surrealism ― an inherently playful movement which sought to express the unity of the conscious and unconscious through art ― had taken firm root in Europe. Initially, as with so many Surrealist works, the movie and the director himself received a mixed reception stateside. (Variety, for instance, called Blood a “hopeless mess.”)

But as he continued to produce work, Cocteau came to be seen as a significant cultural player by, as LIFE magazine once put it, “U.S. highbrows.”

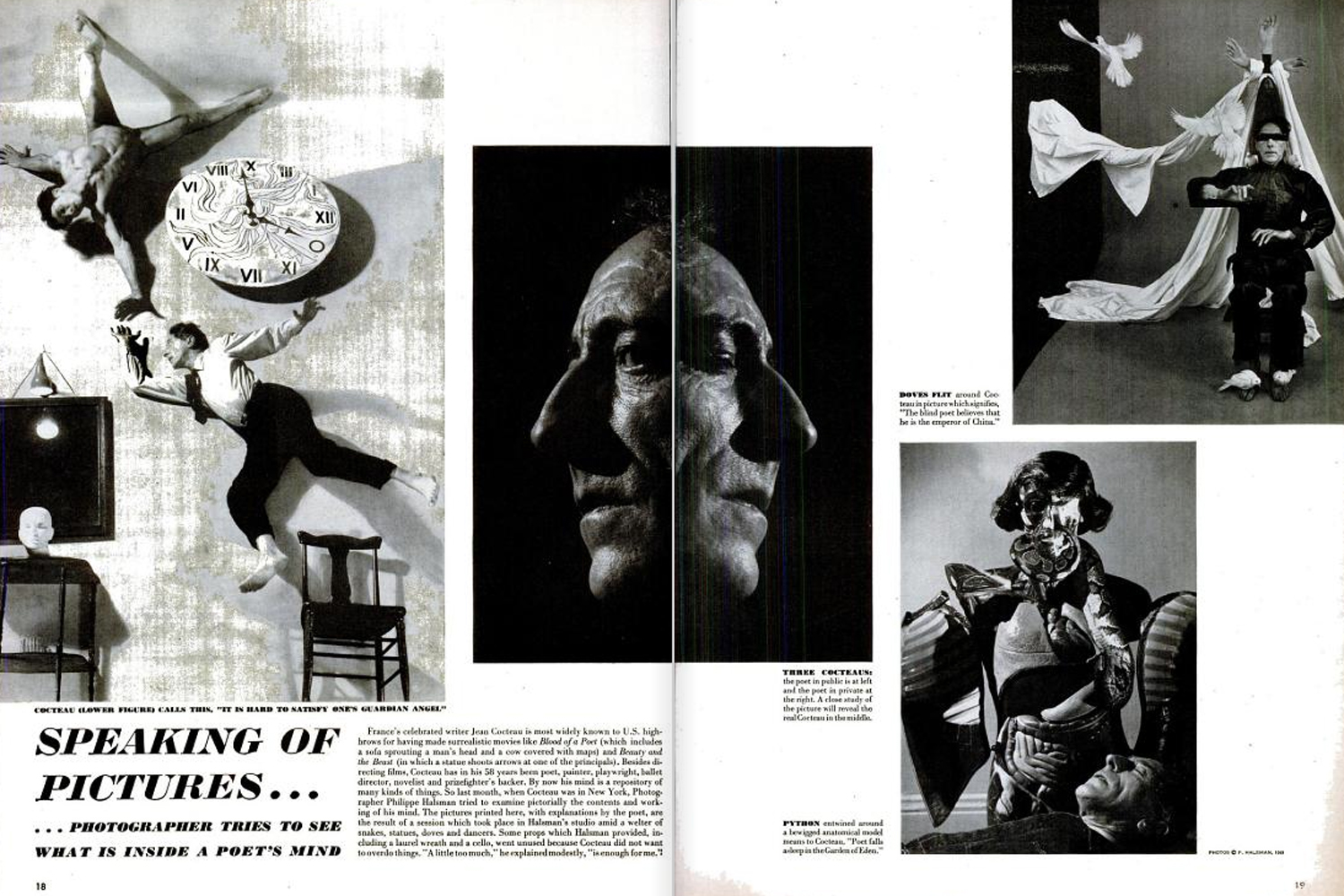

In 1949, LIFE commissioned photographer Philippe Halsman to produce a photo essay on Cocteau, in order to try and illustrate what happens “inside a poet’s mind.” The results were delightful.

Spread across three pages (see slide #2 above and image at left), nearly all of Halsman’s pictures made reference, in some way, to Cocteau’s work. In one, the poet hovers above a chair, as if weightless; in another we see him creeping down a corridor as arms reach out from the walls ― a vision that recalls a memorable scene in Cocteau’s gorgeous 1946 film, Beauty and the Beast. We see him in profile over the centerfold (twice!), his brow furrowed, as if contemplating some great mystery.

Halsman’s most striking image, though, was not published in the magazine. It shows Cocteau wearing a jacket back-to-front, while he smokes, reads and brandishes scissors all at once. It’s a photograph that thrillingly captures the artistic temperaments of both Cocteau, the artist, and Halsman, the photographer, with seeming ease.

While Cocteau had, by 1949, proven himself a multifaceted poet, filmmaker, painter and even ballet director, Halsman was famous for his masterful command of one trade: producing striking images that were compositionally simple, but stylistically experimental. Halsman, too, was an early embracer of surrealist tenets, and as a close friend of Salvador Dali could not have been a more a perfect fit for the assignment.

Indeed, to photograph a quirky subject like Cocteau in a pretty straightforward studio setting was in keeping with two of Halsman’s rules of photography ― rules he later outlined in his 1961 book, Halsman on the Creation of Photographic Ideas: keep it simple, but make it special.

And special his Cocteau shoot emphatically was. Dramatic and inventive, Halsman’s pictures not only capture the levity, the playfulness, of surrealism as a movement. In an elemental way, they also celebrate the spirit of two men who were unafraid to push boundaries ― to go that little bit further.

Richard Conway is a member of TIME.com’s photo staff. He’s previously written for TIME’s LightBox on Enrique Meneses, Erwin Olaf, Gary Winogrand, Ezra Stoller and Peter Hujar.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com