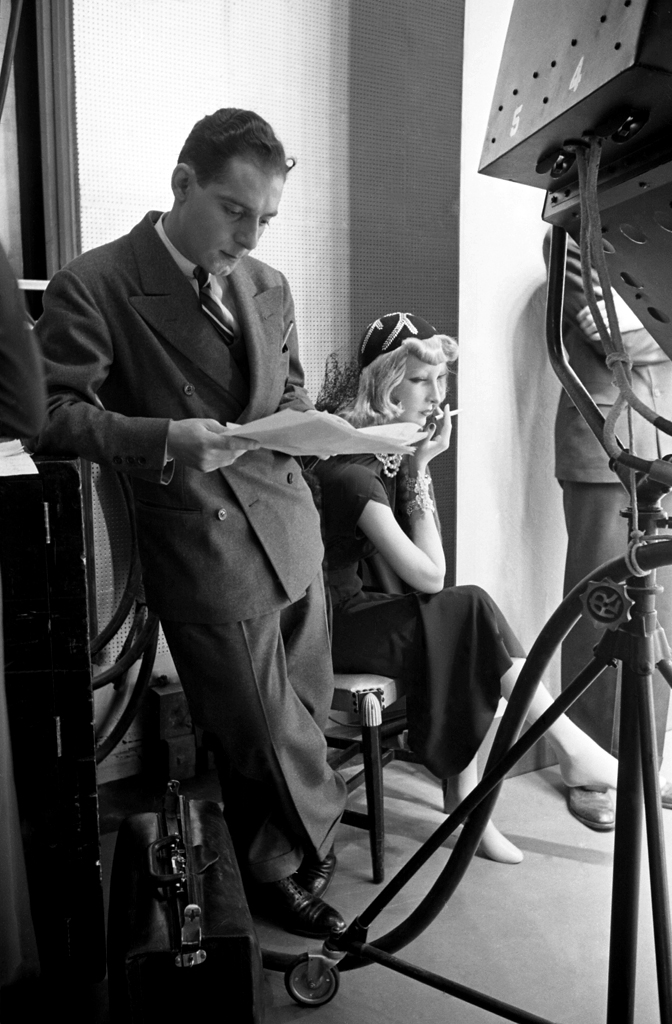

In 1937, LIFE magazine launched the career of an up-and-coming starlet in a multiple-page photo spread that, overnight, made “Cynthia” a household name. In very short order she became an A-list celebrity; was given her own television talk show and starred on the silver screen; was sent jewels and dresses by top fashion houses; was briefly engaged to one of radio’s biggest stars; and became one of the most recognizable faces in the fashion world.

There was just one minor catch: Cynthia was a mannequin. Not a mannequin in the way a runway model is a mannequin. But a mannequin mannequin. A made-of-plaster mannequin.

Cynthia’s story begins in a small Midwestern town in the early part of the 20th century. Her creator, Lester Gaba, was a Hannibal, Missouri, shopkeeper’s son with dreams of a grand life in the big city. He achieved it through his uncanny skill at one of the Great Depression’s quirkier national crazes — soap sculpting. Buoyed by the fame he earned as a soap sculptor, Gaba moved first to Chicago, then to New York City in 1932, where he went into fashion and retail and pioneered the design of department-store windows. (One story has it that moved to New York to be close to his reputed lover, the stage and film director Vincent Minnelli.)

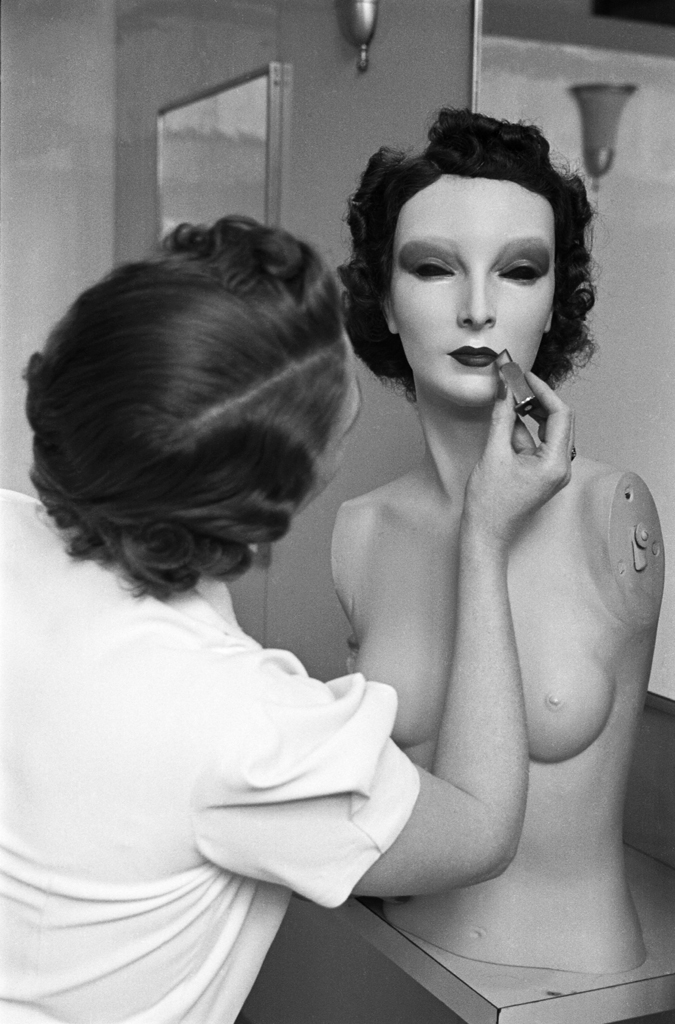

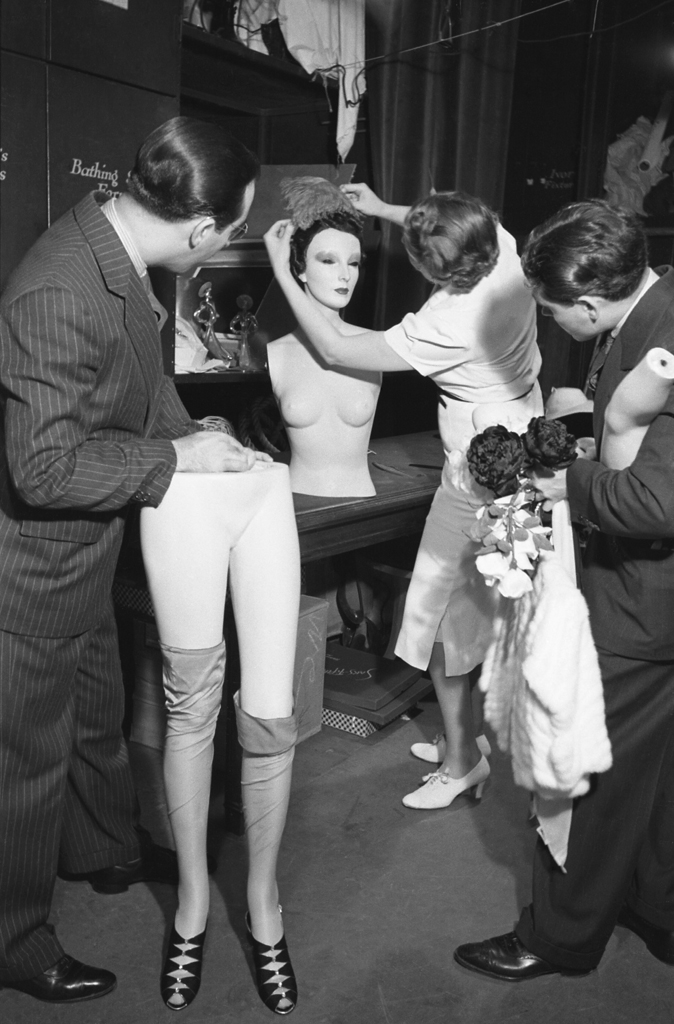

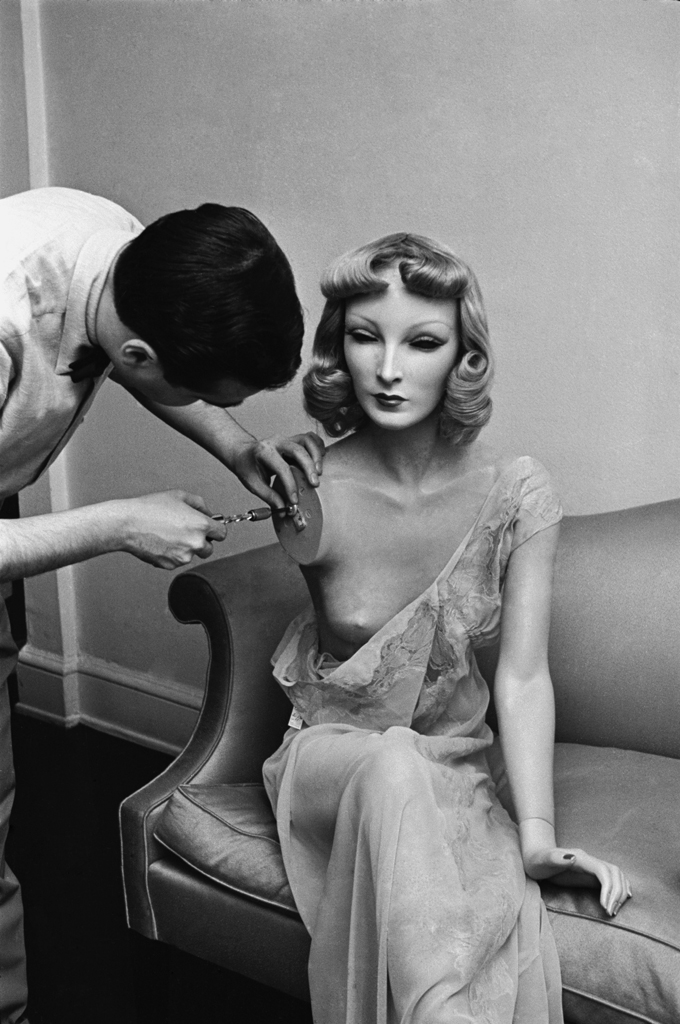

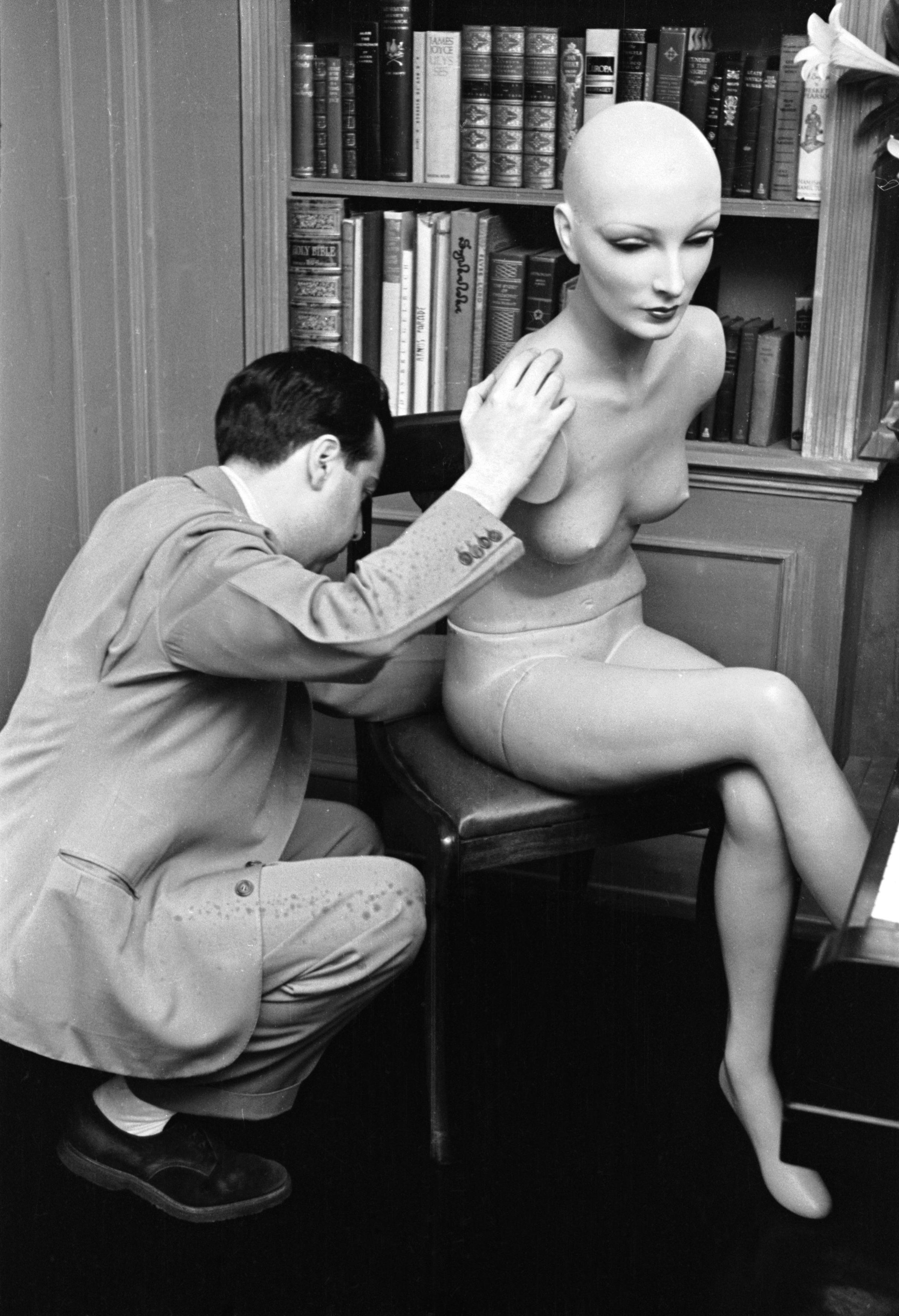

Only years before Gaba came on the scene, mannequins were often still ponderously heavy, relatively unrealistic creations of wax. They melted in the summer heat, and even sometimes bore frightening rictus grins of real human teeth. Upper-class women preferred to see how their clothes looked by having them modeled on young, human women. Gaba was one of a wave of pioneers making modern mannequins that combined style with realism — his so-called “Gaba Girls.”

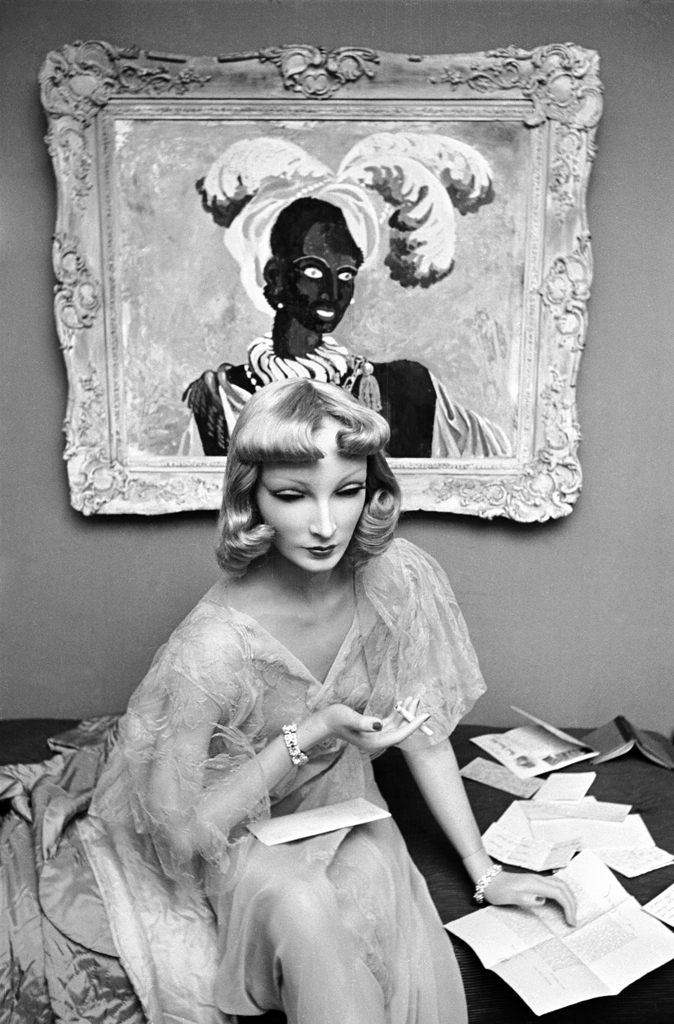

Gaba boasted that his mannequins were nearly indistinguishable from well-dressed human women, and pointed out that his creations had charming imperfections just as real women did, such as freckles and different-sized feet.

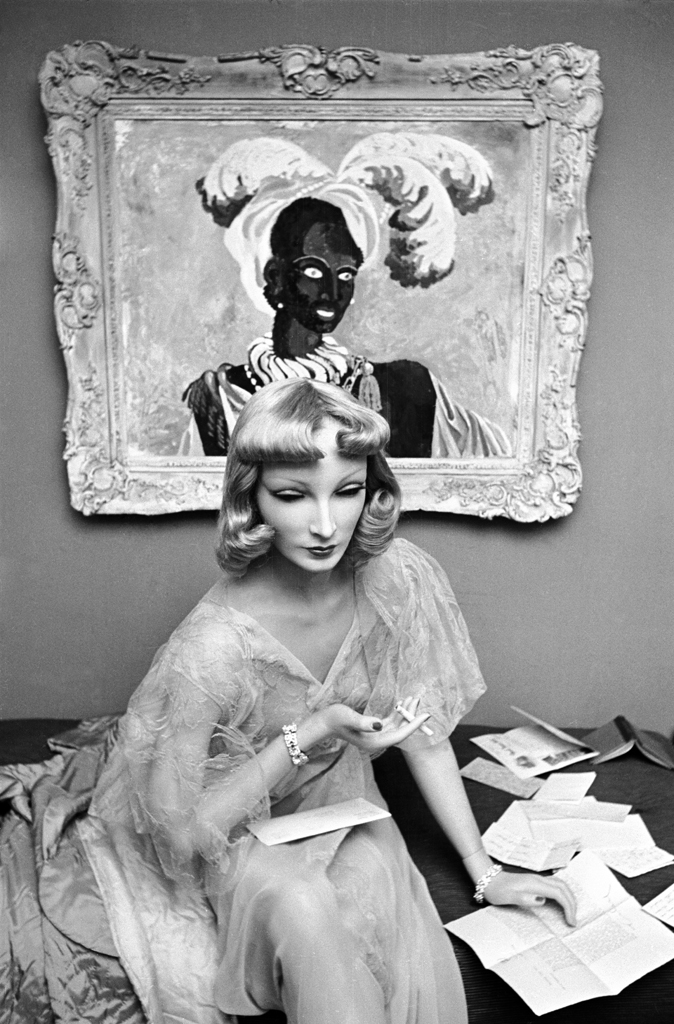

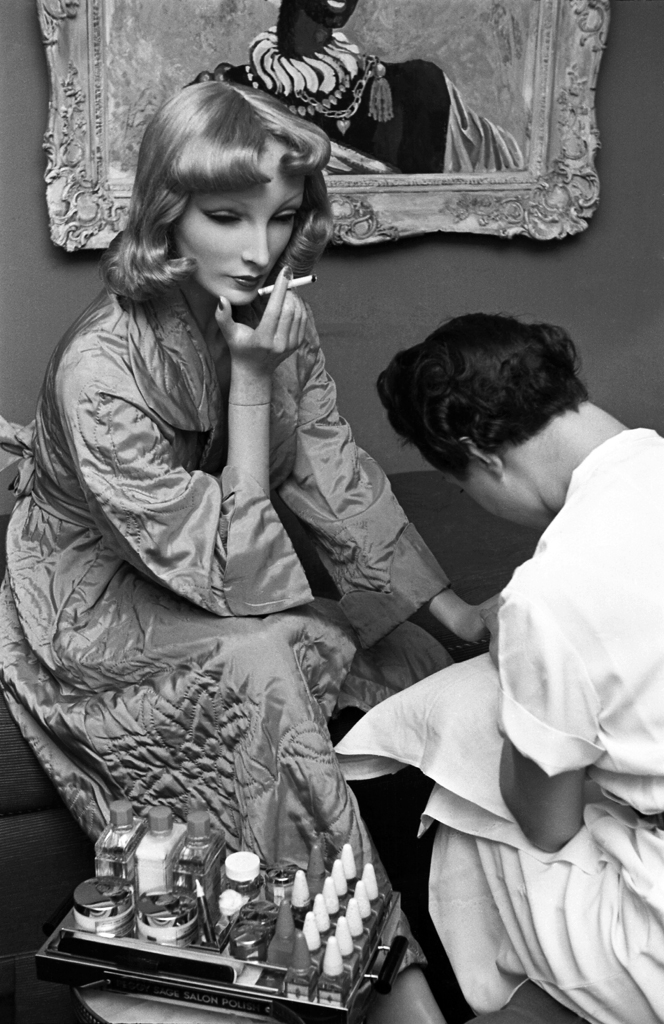

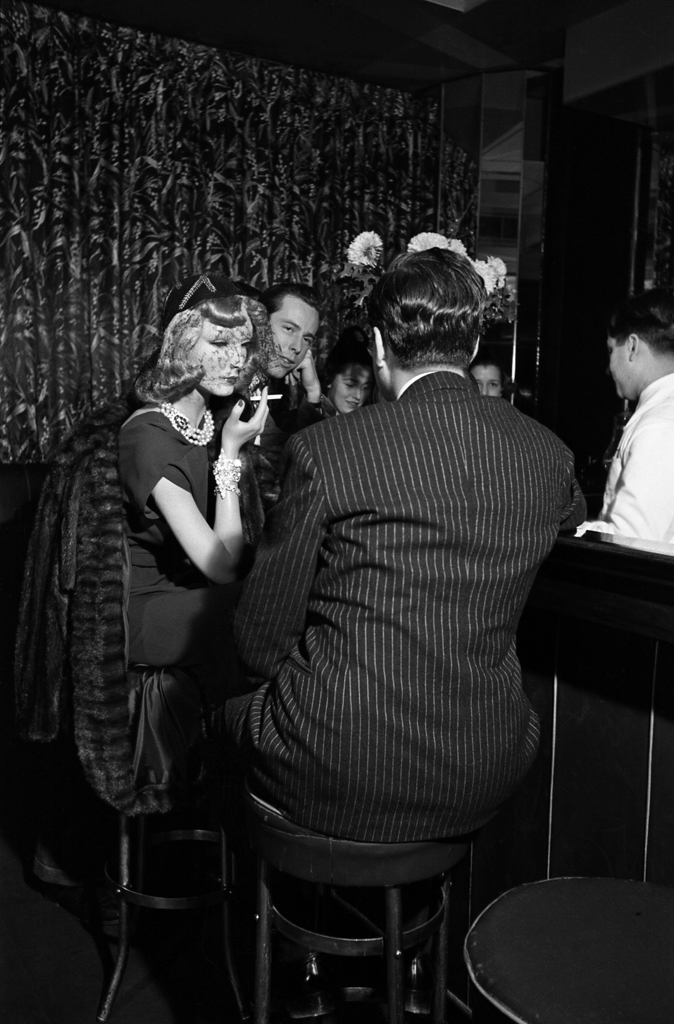

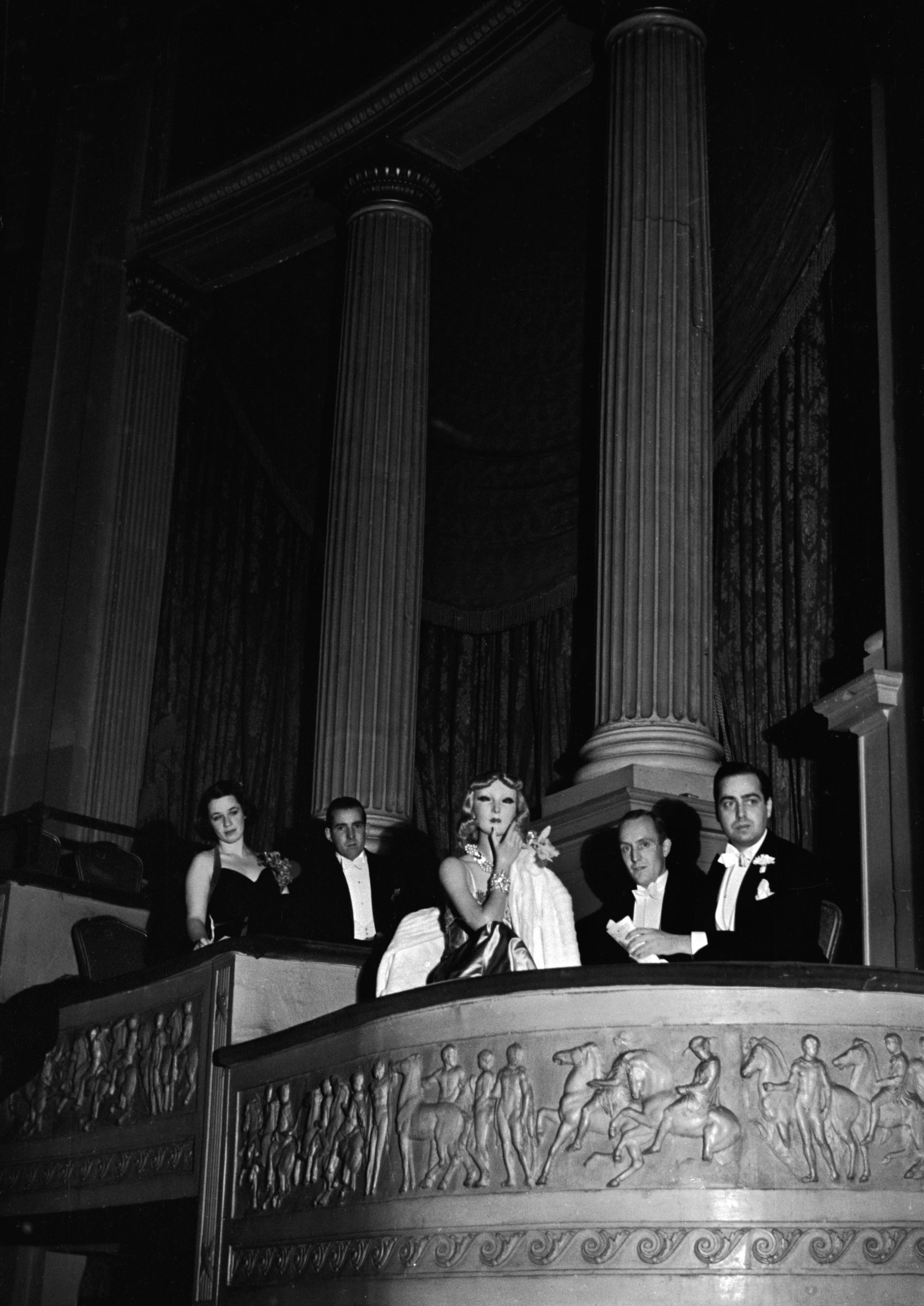

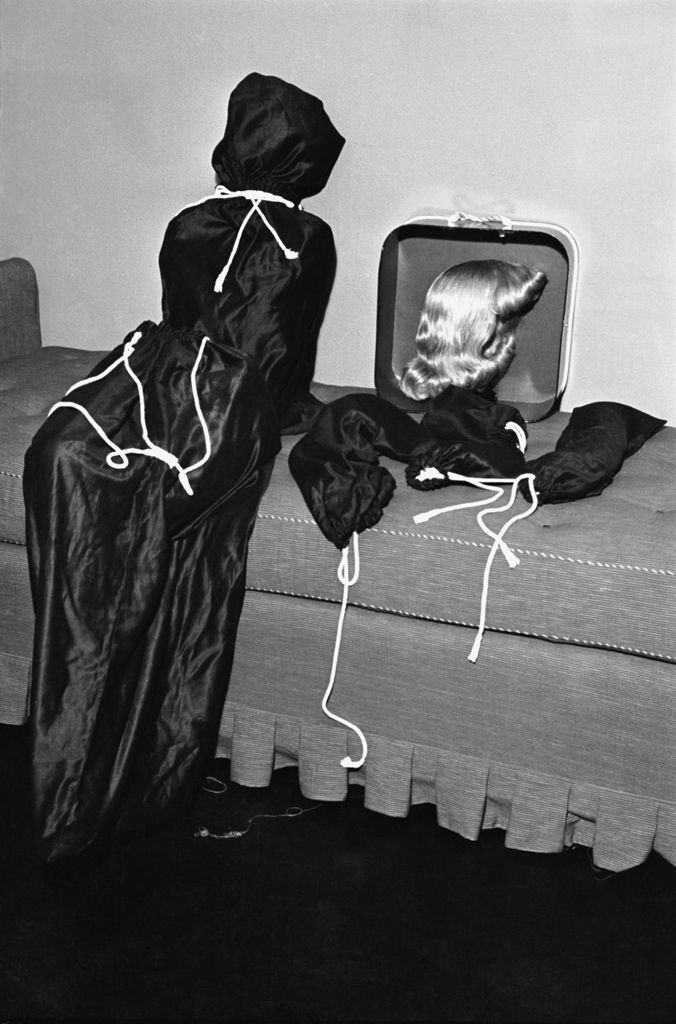

But the undisputed magnum opus of Gaba’s career came in the form of a 5′ 6″, 100-pound doll he dubbed Cynthia. He brought her with him to nightclubs and social events. She became something of a New York nightlife fixture. Meanwhile, the country’s finest stores lavished Cynthia with attention — and free gifts of dresses, shoes, furs and jewelry. Saks Fifth Avenue even issued her a credit card.

Once she achieved a certain level of fame, gossip columnists began writing about Cynthia as if she were a living, breathing socialite. When partygoers tried to engage the mannequin in conversation, Gaba begged off by claiming she was suffering from a touch of laryngitis.

But, as with the fame that sometimes descends on flesh-and-blood humans, Cynthia’s was not to last. Her time in the spotlight proved fleeting, and the next decade saw her begin to fade from public view. In 1942, Gaba was inducted into the army. He sent Cynthia to stay with his mother in Missouri. Though the rest of the nation had moved on to other fads, Gaba insisted that Cynthia be treated like a celebrity, and instructed his mother to take the mannequin to the beauty parlor regularly.

Cynthia’s current whereabouts, if she’s still in one piece (or multiple pieces) are today a mystery. Ultimately, she even remained an enigma to the man who had lavished so much of his talent and his time on her. Years later Gaba admitted to the New York Times‘ Gay Talese that, in the end, “Cynthia never made any sense.” To this day, there’s no satisfactory answer to the question of why a plaster, unsmiling mannequin once thoroughly seized the American popular imagination. Maybe, just maybe, we’re all dummies.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com